|

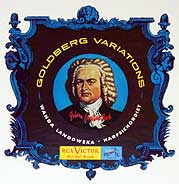

It seems so ironic  - one of the supreme masterworks of music, which has enthralled legions of scholars and performers for ages, was meant to put its first audience to sleep! - one of the supreme masterworks of music, which has enthralled legions of scholars and performers for ages, was meant to put its first audience to sleep!

The so-called Goldberg Variations of Johann Sebastian Bach (1685 - 1750) is believed to have been a gift to a Count Kayserling, an influential musical devotee who had secured for Bach an appointment as official composer to the Saxon court. Beyond being a deep honor, the title provided Bach much-needed royal protection against the pettiness of his employers, with whom he rarely got along. From his earliest days as a church organist, Bach was faulted for confusing congretations with flights of invention rather than strictly accompanying their hymns. Throughout his career, he constantly railed against the inadequacy of the players and resources with which he had to work. an influential musical devotee who had secured for Bach an appointment as official composer to the Saxon court. Beyond being a deep honor, the title provided Bach much-needed royal protection against the pettiness of his employers, with whom he rarely got along. From his earliest days as a church organist, Bach was faulted for confusing congretations with flights of invention rather than strictly accompanying their hymns. Throughout his career, he constantly railed against the inadequacy of the players and resources with which he had to work.

The Count suffered from bouts of insomnia and had hired one of Bach's finest pupils, the fourteen-year old Johann Gottlieb Goldberg, to play for him during his restless nights. To soothe the Count, Bach wrote this piece, formally entitled Aria With Diverse Variations for Harpsichord with Two Manuals, in 1741. In gratitude, the Count sent Bach 100 louis d'or, an extraordinary sum far exceeding his annual salary.

Bach clearly cherished the Variations himself, as they comprised one of only four volumes of keyboard works he published. Yet, while Bach was revered during his lifetime as a great organist who could brilliantly improvise an entire two-hour concert, his compositions were largely dismissed as the type of functional and disposable material which all performers of the time were expected to produce routinely for their own use.

We now acclaim Bach's art as the culmination of a millennium of musical development. Serious Western music began in the Middle Ages with Gregorian chant, a stylization of speech in which a bare melody imitated the verbal inflection of prayer. Chant was a continuous horizontal art, using a single note at a time. The first glimmer of change came around 1100 by adding another voice at the octave, fifth or fourth. Next, melodies were added above the foundation of a chant. Polyphony flowered as up to four independent voices competed for attention. By the 18th Century, the system had matured into an extraordinary profusion of forms, harmonies and rhythms.

Bach's Art of Fugue and Well-Tempered Clavier are often considered the apex of polyphony and the purest expression of his creativity. But perhaps the ultimate display of the full range of Bach's art, as well as the outlet for his deepest, most personal feelings is the Goldberg Variations. Like all great music, the key to understanding it lies in admiring its fantasy and ingenuity within formal restrictions - freedom within limits.

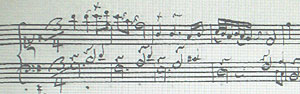

Bach begins and ends with a simple,

The beginning of the aria from Bach's autograph score |

gracious, unadorned song (the aria) he had written years earlier for his wife. Unlike most variations that focus upon a melody, the Goldberg set follows only the bass of Bach's song and its implied harmonies. Each of the thirty variations retains the aria's structure of two 16-bar halves, the first rising from tonic to dominant, and the second, through a chromatic excursion, returning back home to the tonic. But within that basic design, they comprise an amazing abundance of styles and moods. Every third variation is a canon in which regular repetitions of a simple melody overlap and intermingle (as in “Row, Row, Row Your Boat”). The first canon (variation # 3) is in unison (ie: each repetition begins on the same note as the original), and then the intervals increase: #6 is at the second, #9 at the third, all the way up to #27 at a ninth. Bach clearly was intrigued with such formal possibilities - his personal copy of the Goldberg Variations, found only in 1975, contained sketches for 14 more canons on the same bass.

In between the canons

The same passage in a modern edition |

are a lusty dance (#4), a graceful waltz (#7), a fugue (#10), swirling harp-like arpeggiations (#11), a dreamy reverie (#15), an overture (#16), a quidoblet (#30, in which Bach combines two folk songs) and, most striking of all, an astoundingly modern-sounding chromatic meditation (#25) in which all conventional notions of tempo are suspended. The technique ranges from rudimentary two-parts (the aria itself) to fiendishly difficult passages of rapid note clusters (#s 14 and 23), blindingly fast trills (#28) and a furious sinuous line split between the hands (#29) (the intertwining parts of which are far harder to realize on modern instruments than on those of Bach's time which had a separate keyboard for each hand).

Bach never expected his music to survive him. Indeed, toward the end of his life polyphonic music like the Goldberg Variations, in which each voice was of equal importance, was already considered old-fashioned. Even his own sons were pioneering a new and simpler style of harmonized melodies which would form the basis for nearly all the music we now love.  While Mozart, Beethoven and other professionals would become enthralled with the structural marvels of Bach's finely-crafted polyphony, the public relegated both the music and the harpsichord for which it was written to museums and ancient texts. While Mozart, Beethoven and other professionals would become enthralled with the structural marvels of Bach's finely-crafted polyphony, the public relegated both the music and the harpsichord for which it was written to museums and ancient texts.

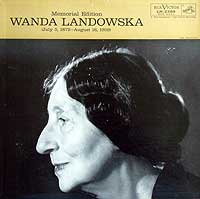

There they languished until 1903, when a young Polish pianist launched their revival. Through the remaining six decades of her life, Wanda Landowska tirelessly researched, taught, performed and crusaded for the harpsichord (in which strings are plucked with quills rather than struck with a padded hammer, as in a piano) and for “authentic” Bach, albeit through the filter of her own considerable ego. Her concerts were theatrical events, given from stages set as Baroque living rooms, as if to demand that audiences enter an antiquated world and meet her only on her own terms.  Landowska also generated one of the great put-downs of all time – when a pianist dared to criticize her performance, she replied: “That's fine - you play Bach your way and I'll play Bach his way!” Landowska also generated one of the great put-downs of all time – when a pianist dared to criticize her performance, she replied: “That's fine - you play Bach your way and I'll play Bach his way!”

Given her crucial role in restoring Bach to public favor, it's fitting that Landowska waxed the very first recording of the Goldberg Variations in 1933 (now on EMI 61008, coupled with a massively dramatic Chromatic Fantasy and Fugue). Unfortunately, the crude sound largely obscures the delicate texture and sparkling harmonics that give the harpsichord its distinctive flavor, a problem only partially cured in her 1946 remake (BMG 60919). Despite her fervent advocacy, and although a revelation in its time, Landowska's playing is dignified, reserved and somewhat stodgy and graceless, although charged with a compelling sense of humanism and commitment that remains deeply touching. Although the harpsichord is impervious to touch, producing the same volume and tone no matter how a key is pressed, Landowska compensates for the fixed dynamics by intensively coloring her tone through exploiting various registers of her custom-built instrument.

A second pioneer was another young pianist, Canadian Glenn Gould, who chose the Goldberg Variations for his sensational debut recording in 1955.  In marked contrast to Landowka's deference to authenticity, Gould regarded Bach as ripe for modern exploration and realized his deeply personal vision of extreme tempos, huge dynamics and phenomenal technique on a concert grand. His album (on Sony SK 52594) still startles with its precision, crisp rhythms and dazzlingly clear counterpoint. Vibrant and exciting, yet deeply respectful of the inherent values of the source, it ushered in modern enthusiasm for Bach by combining the feel of a harpsichord with the romantic impulse and augmented resources of the piano - several variations are blindingly swift, while in the heart-rending 25th time nearly stands still, hanging on each poignant note. In marked contrast to Landowka's deference to authenticity, Gould regarded Bach as ripe for modern exploration and realized his deeply personal vision of extreme tempos, huge dynamics and phenomenal technique on a concert grand. His album (on Sony SK 52594) still startles with its precision, crisp rhythms and dazzlingly clear counterpoint. Vibrant and exciting, yet deeply respectful of the inherent values of the source, it ushered in modern enthusiasm for Bach by combining the feel of a harpsichord with the romantic impulse and augmented resources of the piano - several variations are blindingly swift, while in the heart-rending 25th time nearly stands still, hanging on each poignant note.  If portions seem a bit sterile and more inspired by the editing block than the human soul, a live 1959 Salzburg version (Sony SMK 52685), tempers the studio volatility with more feeling and atmosphere. One of Gould's final projects was a 1981 remake (Sony SMK 52619), in which his former fire and impulse cede to finely-graded dynamics, control and spirituality. If portions seem a bit sterile and more inspired by the editing block than the human soul, a live 1959 Salzburg version (Sony SMK 52685), tempers the studio volatility with more feeling and atmosphere. One of Gould's final projects was a 1981 remake (Sony SMK 52619), in which his former fire and impulse cede to finely-graded dynamics, control and spirituality.

In the last half-century, the popularity of the Goldberg Variations has soared. A Japanese website having charmingly fractured English and the clever URL of www.a30a.com (get the pun?) catalogues 240 recordings (plus hundreds of reissues) on LP and CD, ranging from the traditional harpsichord or piano to arrangements for strings, organ, band and the Canadian Brass. If Bach could return after a quarter millennium, surely he would be astounded!

Of the several dozen renditions currently available, one of the most distinctive is by Rosalyn Tureck (DG 459 599), which contains a marvelous CD ROM feature of a score which can be printed or followed on screen and which compels appreciation for Bach's wondrous construction. In addition, a MIDI element lets you experiment with dynamics, phrasing, embellishments and tempos to craft your own performance (and learn the artistic value of these techniques in the process). As for Tureck's rarefied, magisterial performance, which contains a marvelous CD ROM feature of a score which can be printed or followed on screen and which compels appreciation for Bach's wondrous construction. In addition, a MIDI element lets you experiment with dynamics, phrasing, embellishments and tempos to craft your own performance (and learn the artistic value of these techniques in the process). As for Tureck's rarefied, magisterial performance, it's a throwback to Bach's culture, light-years removed from our present age of constant and immediate gratification. Her deliberate unfolding of a multi-layered masterpiece observes all repeats and consumes 91 minutes (Gould's ran 37!), charging every phrase with cosmic weight and emerging as a profound experience. it's a throwback to Bach's culture, light-years removed from our present age of constant and immediate gratification. Her deliberate unfolding of a multi-layered masterpiece observes all repeats and consumes 91 minutes (Gould's ran 37!), charging every phrase with cosmic weight and emerging as a profound experience.

Equally personal is the 1968 recording by Maria Yudina (Philips 456 994), who played as she lived - an outcast religious dissident in Communist Russia whose irrepressible sense of freedom kindled her artistry. Sharing Bach's belief in music as a direct route to God, she plays every note with a gripping conviction and even adds her own embellishments. Yudina's Goldbergs combine enormously assertive and virile strength with startling dynamics and vast rhythmic elasticity.

Music this rich  will continue to attract great artists and inspire great renditions in every generation. Among the most recent interpreters, Murray Perahia, from July, 2000 (Sony 88243), displays an exquisite sensitivity and breathtaking control, with every phrase beautifully shaped. will continue to attract great artists and inspire great renditions in every generation. Among the most recent interpreters, Murray Perahia, from July, 2000 (Sony 88243), displays an exquisite sensitivity and breathtaking control, with every phrase beautifully shaped.

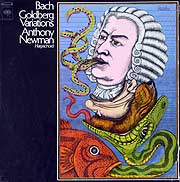

And for the rock generation, those in search of bolder Bach have Anthony Newman, whose bright, bold and insistent 1975 Columbia recording is larger than life, constantly pressing forward with unabashed virtuosity, its impact heightened by close miking for dense registration and immediate sound. Newman concludes not with a dutiful repeat of the aria but with a heavily embellished version that, as his notes observe, complete the monumental work "in the grand style that it so appropriately deserves." His sense of daring is reflected in the bizarre album cover by James Grashaw, which depicts a rainbow of notes issuing from the mouth of the composer, whose bust, in turn, is swallowed by a person, a beaver, a snake and a fish! those in search of bolder Bach have Anthony Newman, whose bright, bold and insistent 1975 Columbia recording is larger than life, constantly pressing forward with unabashed virtuosity, its impact heightened by close miking for dense registration and immediate sound. Newman concludes not with a dutiful repeat of the aria but with a heavily embellished version that, as his notes observe, complete the monumental work "in the grand style that it so appropriately deserves." His sense of daring is reflected in the bizarre album cover by James Grashaw, which depicts a rainbow of notes issuing from the mouth of the composer, whose bust, in turn, is swallowed by a person, a beaver, a snake and a fish!

Still not convinced?  To test the waters, you might try Christiane Jaccottet on Point 265011. Despite incorrectly labeled tracks, minimal packaging and a rushed and ineffective variation #25, and while lacking the vision and polish of the others, it sells for a pittance yet manages to convey the basic idea well enough. To test the waters, you might try Christiane Jaccottet on Point 265011. Despite incorrectly labeled tracks, minimal packaging and a rushed and ineffective variation #25, and while lacking the vision and polish of the others, it sells for a pittance yet manages to convey the basic idea well enough.

Could I ever imagine these compelling records lulling me to sleep? Not in my wildest dreams!

Copyright 2002 by Peter Gutmann

|