|

I took a lot of flack after suggesting in a previous column that John Cage's super-minimalist 4'33" was one of the greatest pieces of music ever written. Not to be deterred, I'll tackle an even riskier judgment – the most beautiful piece of all. Of course, one man's grand opera is another's didgeridoo – beauty is an intensely private opinion, wholly dependent upon culture, personality and, above all, memories. that John Cage's super-minimalist 4'33" was one of the greatest pieces of music ever written. Not to be deterred, I'll tackle an even riskier judgment – the most beautiful piece of all. Of course, one man's grand opera is another's didgeridoo – beauty is an intensely private opinion, wholly dependent upon culture, personality and, above all, memories.

Between college and life I spent a summer traveling on a Eurailpass.  Forget planning – if a place looked interesting as the sun rose, I'd get off the train, spend the day, have a decent meal and then get back onboard – not much scenery in the dark, but no hotel bills or grungy hostels either and just about the only way to really do Europe, as the guidebook then claimed, for $10 a day. One dawn, a gorgeous mountain caught my eye in the foothills of the French Alps, so I alighted at the next stop for a day of discovery. A flyer announced a free concert that evening in a church near the station, so between dinner and that night's train I got a rare soupçon of culture. Forget planning – if a place looked interesting as the sun rose, I'd get off the train, spend the day, have a decent meal and then get back onboard – not much scenery in the dark, but no hotel bills or grungy hostels either and just about the only way to really do Europe, as the guidebook then claimed, for $10 a day. One dawn, a gorgeous mountain caught my eye in the foothills of the French Alps, so I alighted at the next stop for a day of discovery. A flyer announced a free concert that evening in a church near the station, so between dinner and that night's train I got a rare soupçon of culture.

The concert began with one of Beethoven's few clunkers, his slight and tedious Octet, in a dreary performance no one but the local amateurs' parents could possibly have enjoyed. Courtesy barred escape until the interminable thing ended but then, just as polite applause announced my deliverance, a harp was wheeled out and I was hooked, unable to resist my first chance to hear that gentle monster sprung from its customary lair buried deep within a full orchestra. The formalistic title in the mimeo program sounded forbidding, and I'm sure the rendition was at best routine, but perhaps it was the time and the place (or the wine that was cheaper than water) – I was utterly enthralled. To this day, Maurice Ravel's 1907 Introduction and Allegro For Harp, Flute, Clarinet and String Quartet remains the most beautiful music I ever heard. in a dreary performance no one but the local amateurs' parents could possibly have enjoyed. Courtesy barred escape until the interminable thing ended but then, just as polite applause announced my deliverance, a harp was wheeled out and I was hooked, unable to resist my first chance to hear that gentle monster sprung from its customary lair buried deep within a full orchestra. The formalistic title in the mimeo program sounded forbidding, and I'm sure the rendition was at best routine, but perhaps it was the time and the place (or the wine that was cheaper than water) – I was utterly enthralled. To this day, Maurice Ravel's 1907 Introduction and Allegro For Harp, Flute, Clarinet and String Quartet remains the most beautiful music I ever heard.

(My apologies to those who can't fathom the thought of anything French being beautiful nowadays, but we're talking about the permanence of historical culture rather than the shifting tides of political correctness. And even if you want to hold parents guilty for the sins of their great grandchildren, the fastidious Ravel never married and had no offspring.)

The harp is an amazing instrument with a history stretching to the dawn of recorded civilization.  Archeology and ancient art document harps in Persia, Mesopotamia, Greece, Egypt, India and Africa over 5,000 years ago. Its most famous player was the Biblical King David, whose Psalms are thought to be lyrics to songs he sang to his own harp accompaniment. From its birth, the instrument consisted of a set of plucked sequentially-tuned open strings stretched between a resonator and a curved or angled neck. Through the early Renaissance, with music firmly grounded in a given mode, a single set of diatonic fixed strings sufficed. But once music took harmonic flight expansion was needed. Archeology and ancient art document harps in Persia, Mesopotamia, Greece, Egypt, India and Africa over 5,000 years ago. Its most famous player was the Biblical King David, whose Psalms are thought to be lyrics to songs he sang to his own harp accompaniment. From its birth, the instrument consisted of a set of plucked sequentially-tuned open strings stretched between a resonator and a curved or angled neck. Through the early Renaissance, with music firmly grounded in a given mode, a single set of diatonic fixed strings sufficed. But once music took harmonic flight expansion was needed.

Around 1500, the double-strung harp was introduced, consisting of primary strings tuned to C major and a second set for accidentals. The triple harp followed, with two outer rows of matched strings and the chromatic notes inside. While the design added resonance from the sympathetic vibrations and facilitated rapid repeated notes, it challenged players to smoothly integrate the inner rank. That test was met with the pedal harp, which provided a system of pedals and hooks to stop and raise by a half-tone the strings for each note of the scale (ie: one pedal changed every "D" to "D sharp," another affected every "E," etc.).  The fully-developed harp, in place around 1810, features "double action," which afford each pedal a second position to raise its strings a full tone. How do you flatten a note? Easy – harps routinely are tuned in the scale of C-flat so the flats are available without any pedal, naturals with the first position and sharps with the second. The fully-developed harp, in place around 1810, features "double action," which afford each pedal a second position to raise its strings a full tone. How do you flatten a note? Easy – harps routinely are tuned in the scale of C-flat so the flats are available without any pedal, naturals with the first position and sharps with the second.

Through nearly its entire history, music for the harp was barely distinguishable from music for keyboard, comprising individual plucked melodic notes and accompaniment, with an occasional guitar-like strummed chord tossed in. Despite the huge proliferation of instrumental music during the Baroque and classical eras, the harp was generally ignored. While Handel composed a single lovely harp concerto (his Op. 6, # 4) and Mozart tentatively offset the harp's unique sonority in a double concerto with flute, Vivaldi wrote nothing at all for the harp, even though he produced hundreds of concerti seemingly for every conceivable combination of instruments (including three for mandolin). In the 1800s, as orchestras grew from a few dozen to a hundred or more players, harps occasionally added their wash of sound to atmospheric, transitional or climactic passages, but solo opportunities remained scarce.

Speaking of opportunities, while men dominated performance on every other instrument, for hundreds of years the harp was, and remains, the province of women.  There’s a clear fascination (at least for men) in seeing such a heavy and unwieldy contraption delicately balanced on a soft shoulder nestled in flowing formal gowns, and something ineffably feminine in the grace and refinement of gestures that tame it with a gentle caress. (True, Harpo Marx was a guy, but his choice of instrument deepened his lusty primal character with sexual ambiguity.) There’s a clear fascination (at least for men) in seeing such a heavy and unwieldy contraption delicately balanced on a soft shoulder nestled in flowing formal gowns, and something ineffably feminine in the grace and refinement of gestures that tame it with a gentle caress. (True, Harpo Marx was a guy, but his choice of instrument deepened his lusty primal character with sexual ambiguity.)

In 1903, the Pleyel instrument company commissioned Claude Debussy to write a piece with orchestra to flaunt their brand new chromatic harp, in which all twelve strings per octave were evenly spaced in a single row, thus eliminating the need for constant use of the pedals for passages of rapidly shifting tonality. His 1904 Danses Sacres et Profanes begins with strummed chords over a misty background, and showcases increasingly complex and rapid figurations and harmonies, all amid reticent shadows of the orchestral support.

Not to be outdone, the rival Erard firm, principal manufacturer of the conventional pedal harp, hired Ravel to write a piece to display the expressive range of their instrument. Ravel spent much of his professional life in the shadow of his fellow-Impressionist Debussy. (The five-volume 1908 edition of Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians didn't even list Ravel, although by the 1954 revision his article would be a page longer.) Yet, Ravel was the ideal catalyst to raise the harp to its deserved pedestal of elegance and splendor. While they shared a sensitivity to sonic color, Debussy tended toward sensual mysticism, while Ravel was far more interested in the musical forms of the past and produced elegant and efficient music of delicacy and finesse. hired Ravel to write a piece to display the expressive range of their instrument. Ravel spent much of his professional life in the shadow of his fellow-Impressionist Debussy. (The five-volume 1908 edition of Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians didn't even list Ravel, although by the 1954 revision his article would be a page longer.) Yet, Ravel was the ideal catalyst to raise the harp to its deserved pedestal of elegance and splendor. While they shared a sensitivity to sonic color, Debussy tended toward sensual mysticism, while Ravel was far more interested in the musical forms of the past and produced elegant and efficient music of delicacy and finesse.

While both composers often used harps to color their orchestral scores, Ravel's Introduction and Allegro was the first piece to explore and exploit the full resources of the solo instrument. Essentially a miniature concerto in the remote but harp-friendly key of G-flat major, it begins in a hushed, dry whisper, revels in the interplay of textures of breathy flute, reedy clarinet and plucked and bowed strings, and flits among simple but charming melodic fragments with an exquisitely subtle palette.

Erard's deadline loomed, but Ravel had been invited to go on a private cruise and completed the piece in "a week of frantic work and three sleepless nights." But, as generations of procrastinating students can attest, all-nighters have their dangers, and Ravel, in his haste to pack up and get to the dock, left his precious score behind! Even so, the rushed pace of its composition imparts a freshness and spontaneity nearly unique among his meticulous output.

Ravel's attitude toward the Introduction and Allegro seems ambivalent. He omitted it from his catalog of works and never mentioned it in his autobiography.  Yet, it was included in many of his concerts and was one of only a handful of his works he recorded, and of those the very first. Although cut in the primitive acoustical process, in which sound was gathered by a horn, concentrated on a diaphragm, and etched by a stylus directly onto a wax master, the result is astoundingly clear and detailed. Ravel famously proclaimed that "Performers are slaves," and indeed the only two orchestral recordings he made are rigid and unyielding – the tempo of his 1930 Bolero is invariable and far slower than the score indication (about 63, rather than 76, beats per minute) and his 1932 Piano Concerto with Margaret Long mutes the expressive sensitivity of her other records. Yet, his 1923 Introduction and Allegro (now on Music and Arts CD 703 in a very noisy transfer) is fleet and vital, propelled by wild tempo fluctuation and an overall improvisatory feel. (One suspects that the speed was dictated in part by squeezing the complete work onto two 78 rpm sides; indeed there's an otherwise inexplicable spot (at 5:08) in which the tempo suddenly gallops away in mid-phrase.) Yet, it was included in many of his concerts and was one of only a handful of his works he recorded, and of those the very first. Although cut in the primitive acoustical process, in which sound was gathered by a horn, concentrated on a diaphragm, and etched by a stylus directly onto a wax master, the result is astoundingly clear and detailed. Ravel famously proclaimed that "Performers are slaves," and indeed the only two orchestral recordings he made are rigid and unyielding – the tempo of his 1930 Bolero is invariable and far slower than the score indication (about 63, rather than 76, beats per minute) and his 1932 Piano Concerto with Margaret Long mutes the expressive sensitivity of her other records. Yet, his 1923 Introduction and Allegro (now on Music and Arts CD 703 in a very noisy transfer) is fleet and vital, propelled by wild tempo fluctuation and an overall improvisatory feel. (One suspects that the speed was dictated in part by squeezing the complete work onto two 78 rpm sides; indeed there's an otherwise inexplicable spot (at 5:08) in which the tempo suddenly gallops away in mid-phrase.)

In comparison, the several French recordings which followed emphasize modest grace. Harpist Denise Herbecht with an ensemble led by Pierre Coppola (1931, on Lys 364) trades rhythmic precision to achieve a casual feeling, while an all-star performance by Lily Laskine, with flutist Marcel Moise and the Quatour Calvet (1938, on Lys 298) is meltingly supple with breathtakingly delicate phrasing. the several French recordings which followed emphasize modest grace. Harpist Denise Herbecht with an ensemble led by Pierre Coppola (1931, on Lys 364) trades rhythmic precision to achieve a casual feeling, while an all-star performance by Lily Laskine, with flutist Marcel Moise and the Quatour Calvet (1938, on Lys 298) is meltingly supple with breathtakingly delicate phrasing.

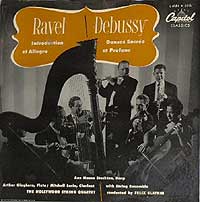

The Gallic hold on recordings ceded in 1951 to Americans Ann Mason Stockton and the Hollywood Quartet, who traded dynamic subtlety and refined atmosphere for super-clean rendition, abetted by Capitol's startlingly vivid recording (Testament 1053). My favorites among stereo contenders are by Osian Ellis and the Melos Ensemble (Decca 952 891), Edward Druzinsky (BMG 63683) and Nicanor Zabaleta (on various DG compilations) – and not because they're guys! The Melos boast keen attention to detailed inflection, Druzinsky's exquisitely close recording is nestled in the lush power of the full string section of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra led by Jean Martinon, and Zabaleta conjures a stunning degree of precision and control – in his cadenza he somehow creates concurrent layers of textures, a truly awesome effect and one of the most amazing feats of musicianship on record.

If you like the Introduction and Allegro, then you should love Ravel's 1903 Quartet, which shimmers with a similar sensibility. The influence of Debussy's own 1893 Quartet is unmistakable, and the two works have been logically paired on LP and now CD. Ironically, though, in their quartets the two composers seem to have switched roles from their harp pieces, with Debussy the more formal and Ravel the more sensual, warm and structurally daring. Ravel supervised and approved the first 1927 recording by the International Quartet (Music and Arts 703) – quite temperate and nondescript (in keeping with his own conducting style). Far more involved are the Quatour Capet (1929, no CD) and Quatour Calvet (1936, Lys 298). Among numerous fine modern versions, the pace was set by the fervent Budapest Quartet in 1958 (Sony MPK 44843). The Travnicek Quartet, sharp and alive, is a standout and an amazing bargain on super-budget Point 267172. then you should love Ravel's 1903 Quartet, which shimmers with a similar sensibility. The influence of Debussy's own 1893 Quartet is unmistakable, and the two works have been logically paired on LP and now CD. Ironically, though, in their quartets the two composers seem to have switched roles from their harp pieces, with Debussy the more formal and Ravel the more sensual, warm and structurally daring. Ravel supervised and approved the first 1927 recording by the International Quartet (Music and Arts 703) – quite temperate and nondescript (in keeping with his own conducting style). Far more involved are the Quatour Capet (1929, no CD) and Quatour Calvet (1936, Lys 298). Among numerous fine modern versions, the pace was set by the fervent Budapest Quartet in 1958 (Sony MPK 44843). The Travnicek Quartet, sharp and alive, is a standout and an amazing bargain on super-budget Point 267172.

Another summer now has passed. I’ve long forgotten the name of that modest town somewhere in the French Alps 30-odd years ago, but nothing can supplant the timeless haunting memory of its beautiful harp.

Copyright 2003 by Peter Gutmann

|