|

There's nothing like a juicy tale to humanize the appeal of rarified art.  One of the most intriguing legends clings to Mozart's Requiem, his final masterpiece left unfinished at his death on December 5, 1791, at the age of a mere 35. One of the most intriguing legends clings to Mozart's Requiem, his final masterpiece left unfinished at his death on December 5, 1791, at the age of a mere 35.

The mischief seems to have begun in 1825, when Aleksandr Pushkin wrote his short verse drama Mozart and Salieri, in which he fantasized that the supremely talented Mozart, upon completing the Requiem, is poisoned by his rival, the mediocre but powerful official court composer. Rimsky-Korsakoff perpetuated the tale in his one-act 1897 opera that used a slight abridgement of the Pushkin drama for its libretto. In his 1978 play Amadeus, Peter Shaffer took a less literal view, depicting a manipulative Salieri who deprives Mozart of recognition by patrons and public and kills him only figuratively with the poison of envy. The myth took its most extreme leap in Shaffer's screenplay for the acclaimed 1984 Milos Forman movie, now embellished so that Salieri completes his triumph by commissioning the Requiem in the guise of a frightening emissary from the Beyond, driving a depressed and destitute Mozart to work himself to death to complete it, copying down the dying composer's final directives, and then claiming the masterpiece as his own. in which he fantasized that the supremely talented Mozart, upon completing the Requiem, is poisoned by his rival, the mediocre but powerful official court composer. Rimsky-Korsakoff perpetuated the tale in his one-act 1897 opera that used a slight abridgement of the Pushkin drama for its libretto. In his 1978 play Amadeus, Peter Shaffer took a less literal view, depicting a manipulative Salieri who deprives Mozart of recognition by patrons and public and kills him only figuratively with the poison of envy. The myth took its most extreme leap in Shaffer's screenplay for the acclaimed 1984 Milos Forman movie, now embellished so that Salieri completes his triumph by commissioning the Requiem in the guise of a frightening emissary from the Beyond, driving a depressed and destitute Mozart to work himself to death to complete it, copying down the dying composer's final directives, and then claiming the masterpiece as his own.

It's an enthralling tale but, alas, wholly false. The central paradox, though, remains compelling – that only another, inevitably inferior composer could truly appreciate Mozart's genius, while being condemned to a lifetime of frustration unable to approach Mozart's brilliance. The motivation, too, is complex, rising above mere envy to a perverse sense of moral obligation, so as to redress the injustice of stupendously brilliant creativity emanating from a scatological boor, and thereby upholding the loftiness of art. While Shaffer framed both the play and movie as a flashback fantasy of a guilt-ridden, decrepit and demented Salieri, the power of his imagery strikes most viewers as an accurate depiction of historical fact. Yet, the real story of Mozart's Requiem is nearly as intriguing and has led to a vexing challenge for modern musicologists.

By 1791, Mozart's career was in eclipse. He no longer attracted audiences to concerts, had few students and had to squander his talent on trivial commissioned music (for a mechanical clock and glass harmonica) and dances for court balls (33 written in January and February alone).  But, as H.C. Robbins Landon has detailed in 1791: Mozart's Last Year, the composer was happily married and only slightly in debt, sent his wife Constanze for extended stays at distant spas and had a nice home, fine clothes and meals brought in by servants. But, as H.C. Robbins Landon has detailed in 1791: Mozart's Last Year, the composer was happily married and only slightly in debt, sent his wife Constanze for extended stays at distant spas and had a nice home, fine clothes and meals brought in by servants.

Yet, something bizarre indeed happened – in July Mozart received a commission for a requiem from a stranger who advanced half the fee and insisted upon anonymity. We now know that the envoy was from a Count Walsegg, an amateur flutist and cellist who sought undeserved lasting fame by claiming authorship of compositions he bought from famous composers. While history has branded Walsegg as a thief, Anton Herzog, a musician in his employ, left a far more benign account – Walsegg liked to entertain guests by challenging them to guess the composer of brand new compositions he performed (and which he copied in his own hand to avoid clues from the original manuscripts). This time, though, the Count had a more serious purpose – a mass to be performed each year to commemorate the death of his young wife.

Unlike most composers of the time, Mozart was far from devout, and had completed little church music. Among many aborted attempts, his only major religious work had been a magnificent 1782 Mass in c minor, brimming with his recent discovery of Bach and Handel, and which he had intended to impress his bride's home town of Salzburg but never finished once the initial ardor cooled, substituting movements from earlier works for a first and only performance. The mysterious commission apparently stimulated his lapsed interest. It's unclear just when Mozart began work on the Requiem, but he soon turned to other commitments, including writing his opera La clemenza di Tito and presenting it in Prague to celebrate the coronation of Leopold II. Upon his return to Vienna in mid-September, he was consumed with completing and staging another opera, Die Zauberflöte ("The Magic Flute"), a clarinet concerto for his friend Anton Stadler and a cantata for his Masonic lodge.

We have conflicting accounts of Mozart's mental state during this crucial period. After Prague, his wife went to a spa in Baden, and (fortunately for posterity) Mozart wrote her often. His letters are wholly upbeat, his mood buoyed by the success of Zauberflöte.  Yet, in the first Mozart biography (albeit not written until 1798), a family friend, Franz Xavier Niemetchek, claims that Mozart's health and spirits plunged, his melancholy thoughts obsessed with paranoid fear of being slowly poisoned, contemplation of his own death, and a gnawing feeling that he was writing his Requiem for himself. Indeed, after her return, upon a doctor's advice, Constanze took the Requiem score away from Mozart but then returned it as his morale improved. Yet, in the first Mozart biography (albeit not written until 1798), a family friend, Franz Xavier Niemetchek, claims that Mozart's health and spirits plunged, his melancholy thoughts obsessed with paranoid fear of being slowly poisoned, contemplation of his own death, and a gnawing feeling that he was writing his Requiem for himself. Indeed, after her return, upon a doctor's advice, Constanze took the Requiem score away from Mozart but then returned it as his morale improved.

Mozart took to his bed on November 20 with what has since been diagnosed as rheumatic fever (complicated by childhood bouts with streptococcal infection). While his debilitating symptoms seem appalling by modern standards, according to his sister-in-law Sophie, he was expected to make a full recovery, as did most victims of the same epidemic. On December 4 his condition declined suddenly and was made even worse by misguided medical care of the time, including bleeding and cold compresses. He died shortly after midnight and was buried the next day following an open-air funeral. For reasons that remain unclear (the weather was fine), no one accompanied the casket to the cemetery, where it was placed in an unmarked common grave that has never been found.

Constanze was devastated by Mozart's sudden death. Yet, despite her depiction in Amadeus as a twit, she had a shrewd business sense and knew that Mozart's scores, most of which remained unpublished, were a valuable asset which she would come to exploit quite well, quickly clearing Mozart's debts and having a good life of her own.  (Not all of her dealing was above-board, though - after presenting the Count with the completed Requiem score, she kept a copy for herself and had it performed at a benefit concert in January 1793, unbeknown to the Count who thought he would be leading the official premiere that December.) But of immediate concern was collecting the remainder of the commission for the Requiem, which had to be finished. (Not all of her dealing was above-board, though - after presenting the Count with the completed Requiem score, she kept a copy for herself and had it performed at a benefit concert in January 1793, unbeknown to the Count who thought he would be leading the official premiere that December.) But of immediate concern was collecting the remainder of the commission for the Requiem, which had to be finished.

Of its 14 sections, Mozart had completed in full score the opening Introitus (an astounding blend of the old polyphony and dignified repressed emotions of Bach with the forward-looking mournful lyricism of the coming era) and the four vocal parts and bass of the Kyrie (a stunning double fugue that symbolically fuses a stern, noble subject for "Kyrie eleison" with a more humanized one for "Christe eleison"). To perform them both at a memorial service, Constanze asked Mozart's foremost pupil F. X. Freystädtler to orchestrate the Kyrie, which he inscribed on Mozart's autograph original (preserved in the Austrian National Library in Vienna). She next gave the score to Joseph Eybler, a close friend who had been with Mozart through much of his final illness and a gifted composer for whom Mozart had written a glowing testimonial and held in high esteem. Mozart had written out the full vocal parts and bass line, together with an outline of the remaining instrumentation, for nearly the entire Sequenz (Dies irae, Tuba mirum, Res tremendae, Recordare and Confutatis), but only the first eight bars of the Lacrimosa. Eybler completed these portions but then stopped at the same point as Mozart, possibly due to other commitments, but, according to Eve Badura-Skoda, more likely out of humility and respect for Mozart, whose inspiration and invention he felt unworthy to succeed.

Finishing the rest of the score was more problematic. Mozart's manuscript contained sketches for the Offeratorium, but nothing at all for the Sanctus, Benedictus and Agnus Dei. Constanze apparently tried to enlist a number of other respected composers but ultimately settled for Franz Süssmayr, a copyist and occasional pupil who happened to have been at the Mozarts' during the composer's final night but for whom Mozart had had little regard - in letters to Constanze that fall, Mozart had called him a blockhead, an ass-licker and a lamp-cleaner and likened his mental acuity to that of a duck in a thunderstorm. The crucial question that has perplexed scholars is how much of the final product qualifies as authentic Mozart.

Until nearly his very end, Mozart had no reason to entrust completion of his Requiem to anyone else, and so the events of the very brief period after he recognized his fatal condition are crucial to assessing how much Süssmayr's work derives from Mozart's sketches and other directives. In a letter written to the score's publisher in 1800, Süssmayr (clearly motivated to enhance his role) claimed that Mozart, Constanze and he had sung through the sketched portions and that Mozart frequently had discussed realization of the remainder with him, including details of orchestration, but that he had composed the three remaining sections "afresh." Both Sophie and Constanze (motivated to legitimize the completed work as the genuine work of her late husband) recalled (decades later) that in his final hours Mozart explained to Süssmayr how to complete the work, including repeating the opening fugue at the end. Constanze further claimed that Mozart always conceived his works in their entirety (which seems consistent with his known methods of working), and that she had provided Süssmayr with scraps of music possibly intended for the work (none of which has ever surfaced). (There have been scattered reports of discovered Mozart sketches intended for the Requiem, but frustratingly none ever mentions the content or how it might relate to Süssmayr's material.)

To prepare his own modern edition, Richard Maunder analyzed Süssmayr's other work, including an imitative Ave verum corpus written the year after Mozart's, and concluded on stylistic and technical grounds that Süssmayr most likely did write the missing portions of the Requiem himself, with the possible exception of the Agnus Dei. Others, though, point to thematic similarities with Mozart's portions (for example, the melody of the Sanctus is identical to that of the Dies Irae) and note that none of Süssmayr's other work exhibits organic unity. They also note that the Requiem so surpasses the consistent mediocrity of Süssmayr's other work as to compel significant input from Mozart. In any event, Süssmayr largely disregarded the Eybler additions, wrote out the entire score in his own hand (so as to allay suspicion of multiple authorship) and forged Mozart's signature (but stupidly dated it 1792!).

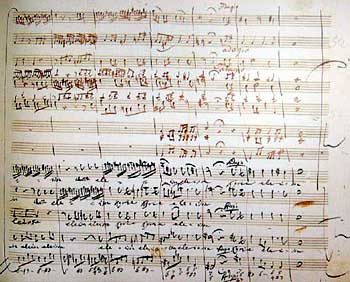

Here is a fascinating document - the final page of the Kyrie fugue of the autograph score before Süssmayr copied it in his own hand (and added his completion) to pass it off as a unified composition.  According to Landon, the bottom five staves in black ink (S-A-T-B voices and the continuo), together with figured bass for an organ, are in Mozart's hand, the top five (for first violins, second violins, viola, basset horns and trombones) are by Freystädtler and the middle two (trumpets and kettledrums) are by Süssmayr. Many later pages of the autograph are far sketchier and, according to Benjamin-Gunnar Cohrs, reflect Mozart's late method of composition - he routinely wrote out the vocal lines first, then openings and transitions, first violin, strings, and finally the rest. (The full manuscript, of which this is a screen shot, is a CD ROM feature on the Harnoncourt CD, noted below.) According to Landon, the bottom five staves in black ink (S-A-T-B voices and the continuo), together with figured bass for an organ, are in Mozart's hand, the top five (for first violins, second violins, viola, basset horns and trombones) are by Freystädtler and the middle two (trumpets and kettledrums) are by Süssmayr. Many later pages of the autograph are far sketchier and, according to Benjamin-Gunnar Cohrs, reflect Mozart's late method of composition - he routinely wrote out the vocal lines first, then openings and transitions, first violin, strings, and finally the rest. (The full manuscript, of which this is a screen shot, is a CD ROM feature on the Harnoncourt CD, noted below.)

Compared to the neglect met by most of Mozart's work until the 20th century, the result garnered huge popularity, even if it was fueled in large part by the myths surrounding its creation. Milton Cross noted: "The chilling awareness that he was dying, and that he was writing his own requiem, brought to his writing an other-worldly beauty and a depth of awareness unique even for Mozart." Indeed, even in comparison with his other late masterpieces, the Requiem is extraordinary, condensing a vast realm of feeling into well less than an hour. Poised between the formal dignity of the great baroque religious works (Bach and Handel) and the visceral bombast of the Romantic Requiems of Berlioz and Verdi to come, it displays a thorough integration of styles within a pervasive sobriety appropriate to the subject (reflected in somber instrumentation of trombones, basset horns and strings in mostly lower registers). Like all great Mozart, it has an expressive depth that forces us to delve beneath the surface for startling emotional richness. It points and beckons rather than pushes.

Those versed in the Mozart style generally agree that Süssmayr's work is deeply flawed with technical errors, needless instrumental doubling of voices and a general lack of inspiration (although few non-scholarly ears notice the faults and, as many concede, what contemporary wouldn't be found lacking when compared to the genius of Mozart?). Yet, the question remains of what, if anything, to do about it. There's little consensus among editors of modern editions and recordings.

As noted in more detail below, the most radical eliminate the Süssmayr material altogether, either leaving a torso with new orchestrations of Mozart's vocals and bass, or substituting realizations of their own. More moderate editors adhere to Süssmayr's basic plan but attempt to correct his "grammatical" mistakes and lighten the instrumentation. As Landon notes in defending this approach, an intimate of the composer, immersed in the traditions of the time, is "far better equipped to complete Mozart's torso than a twentieth-century scholar, however knowledgeable." And in all fairness, while it may lack the inspiration of Mozart, Süssmayr's material has much merit, thus suggesting that the mediocre student must have adhered closely to the master's detailed verbal directives - as Milton Cross put it: "How [else] could music of such grandeur and sublimity possibly [have] come from one who produced nothing else in his life of lasting value?" Intrinsic value aside, the fact remains that audiences have become accustomed to the Requiem taken as a whole, regardless of the extent to which Mozart may not have written all of it.

As a guide to the various editions and recordings, here's an outline of the structure (major divisions in bold and movements in italics), together with indications of the contributors to the standard traditional edition (mostly as identified in the undated Breitkopf & Härtel score reprinted by Dover in 1987):

- Introitus:

- Requiem aeternam - wholly composed by Mozart.

- Kyrie - voices and bass by Mozart; most instruments by Freystädtler, but trumpets and drums by Süssmayr.

- Sequenz:

- Dies irae, Tuba mirum, Rex tremendae, Recordare, Confutatis - voices and bass, together with key details of orchestration (trombone solo in Tuba mirum, horns in Recordare, first violin in Confutatis) by Mozart; originally completed by Eybler, but redone by Süssmayr.

- Lacrimosa - first two measures of strings and six measures of voices and bass by Mozart; the rest by Süssmayr, who essentially extended Mozart's figures throughout.

- Offertorium:

- Domine Jesu - vocals and bass by Mozart; rest by Süssmayr.

- Hostias - same; Süssmayr follows Mozart's indication at the end of the Hostias score of a da capo repeat of the "quam olim Abrahae" fugue from the Domine Jesu.

- Sanctus, Benedictus, Agnus dei - all by Süssmayr, but possibly based on sketches (since lost) or verbal directives by the dying Mozart.

- Communio:

- Lux aeterna - Süssmayr adapts Mozart's music from the Requiem aeternam.

- Cum sanctus - Süssmayr repeats Mozart's music for the Kyrie fugue.

While I haven't attempted to hear all of the many dozen available recordings of the Requiem, I can vouch for at least one using each of the alternative, and arguably more authentic, editions, which I've listed in their degree of departure from the Süssmayr version:

- Franz Süssmayr – The vast majority of recordings - including many by period experts who otherwise demand authenticity in their performances - take the simplest approach by accepting the score Süssmayr produced, with all its flaws, at face value.

Of these, my favorites are the ones that use a full orchestra and chorus of modern dimension and slow the pace for a reverential aura - not authentic, perhaps, but deeply moving. The first of these is of a 1937 concert by Bruno Walter with the Vienna Philharmonic and an all-star cast of soloists (Elizabeth Schumann, Kerstin Thornborg, Anton Dermota and Alexander Kipnis), who present a decidedly nineteenth-century view with heavy vibrato, dramatic pauses preceding each vocal outburst of "Rex tremendae," and a deeply atmospheric Lacrimosa (EMI; 57 minutes); Of these, my favorites are the ones that use a full orchestra and chorus of modern dimension and slow the pace for a reverential aura - not authentic, perhaps, but deeply moving. The first of these is of a 1937 concert by Bruno Walter with the Vienna Philharmonic and an all-star cast of soloists (Elizabeth Schumann, Kerstin Thornborg, Anton Dermota and Alexander Kipnis), who present a decidedly nineteenth-century view with heavy vibrato, dramatic pauses preceding each vocal outburst of "Rex tremendae," and a deeply atmospheric Lacrimosa (EMI; 57 minutes); these touches are attenuated in Walter's 1956 NY Philharmonic remake (now on a Sony CD; 53 minutes), which is expressive in its own right, with choral volume swells and impassioned solos. (Although I've never heard the recording, Victor de Sabata reportedly used 300 singers and 160 players in a 1941 Radio Rome concert.) The first studio recording - and our earliest Requiem recording - seems to be a 1931 set derived from the annual Salzburg Cathedral Concerts led by Joseph Messner for the Christschall label that presents a fascinating stylistic confluence of the romantic (thick, powerful textures) and modern (mostly fleet tempos - 46 minutes total, but without the da capo Hostias fugue); details, though, are largely obscured by vocal-heavy balances, imprecise attacks and blurry sonics. It was followed by a 1941 Polydor set by the famed Bruno Kittel Choir, led by its namesake, and the Berlin Philharmonic (DG CD, 53 minutes) that boasts a rich sonic, straightforward conducting and splendid choral work, although the balances tend to bury the orchestral contributions and Nazi ideology apparently demanded revision of all references to Zion, Abraham, Jerusalem and other Jewish roots of the prescribed text. these touches are attenuated in Walter's 1956 NY Philharmonic remake (now on a Sony CD; 53 minutes), which is expressive in its own right, with choral volume swells and impassioned solos. (Although I've never heard the recording, Victor de Sabata reportedly used 300 singers and 160 players in a 1941 Radio Rome concert.) The first studio recording - and our earliest Requiem recording - seems to be a 1931 set derived from the annual Salzburg Cathedral Concerts led by Joseph Messner for the Christschall label that presents a fascinating stylistic confluence of the romantic (thick, powerful textures) and modern (mostly fleet tempos - 46 minutes total, but without the da capo Hostias fugue); details, though, are largely obscured by vocal-heavy balances, imprecise attacks and blurry sonics. It was followed by a 1941 Polydor set by the famed Bruno Kittel Choir, led by its namesake, and the Berlin Philharmonic (DG CD, 53 minutes) that boasts a rich sonic, straightforward conducting and splendid choral work, although the balances tend to bury the orchestral contributions and Nazi ideology apparently demanded revision of all references to Zion, Abraham, Jerusalem and other Jewish roots of the prescribed text.  Despite some dreadful trumpet playing, Hermann Scherchen and the Vienna State Opera Orchestra (Westminister, 1958, 63 minutes), are supremely attentive to texture and balances, abetted by an exaggerated stereo spread and even greater deliberation. Karl Bohm and the Vienna Philarmonic (DG, 1971, 64 minutes) manage to be measured, yet awesome, majestic and commanding without becoming even a bit ponderous or tedious. As usual, the slowest of all performances is by Sergiu Celibidache and the Munich Philharmonic (1995, EMI, 67 minutes), who achieve an unparalleled spiritual intensity, heavily romanticized but with particular focus on enunciation and vocal inflection. Despite some dreadful trumpet playing, Hermann Scherchen and the Vienna State Opera Orchestra (Westminister, 1958, 63 minutes), are supremely attentive to texture and balances, abetted by an exaggerated stereo spread and even greater deliberation. Karl Bohm and the Vienna Philarmonic (DG, 1971, 64 minutes) manage to be measured, yet awesome, majestic and commanding without becoming even a bit ponderous or tedious. As usual, the slowest of all performances is by Sergiu Celibidache and the Munich Philharmonic (1995, EMI, 67 minutes), who achieve an unparalleled spiritual intensity, heavily romanticized but with particular focus on enunciation and vocal inflection.

- Franz Beyer – For this least intrusive of the modern editions, Beyer applies relatively subtle emendations to the standard Süssmayr version.

Indeed, in the "big band" version of The Academy and Chorus of St. Martin-in-the-Field led by Neville Marriner (Argo, 1977) they're barely apparent. A notably expansive pace emerges with the Bavarian Radio Symphony led by Leonard Bernstein (DG, 1990; 59 minutes), whose own final illness created a spiritual connection, and freedom to add some effective if stylistically questionable personal interpretive touches, such as letting the final note trail off into eternity. Original performance pioneer Nikolaus Harnoncourt and his Concentus Musicus Wein (Deutsche Harmonia Mundi, 2003) pare their forces for a spare sonority from which details clearly emerge, combining classical texture with a wide variety of dynamics and tempos, as in the startling contrast between gripping tension and soothing respite within their Confutatis. The standard stereo recording is fine enough, but the disc also includes an SACD surround-sound layer (which I haven't heard) plus a fascinating bonus - a CD ROM track with a slightly blurry display of Mozart's original autograph, whose pages can be synchronized with the music. The tangible evidence of Mozart's long struggle with this work, in contrast to his usual method of through-composing (writing his last opera in a mere 18 days), is a deeply poignant encounter - the eight-measure fragment of the Lacrymosa that trails off onto an otherwise blank page is believed to be the last thing he ever wrote as his life slipped away. Indeed, in the "big band" version of The Academy and Chorus of St. Martin-in-the-Field led by Neville Marriner (Argo, 1977) they're barely apparent. A notably expansive pace emerges with the Bavarian Radio Symphony led by Leonard Bernstein (DG, 1990; 59 minutes), whose own final illness created a spiritual connection, and freedom to add some effective if stylistically questionable personal interpretive touches, such as letting the final note trail off into eternity. Original performance pioneer Nikolaus Harnoncourt and his Concentus Musicus Wein (Deutsche Harmonia Mundi, 2003) pare their forces for a spare sonority from which details clearly emerge, combining classical texture with a wide variety of dynamics and tempos, as in the startling contrast between gripping tension and soothing respite within their Confutatis. The standard stereo recording is fine enough, but the disc also includes an SACD surround-sound layer (which I haven't heard) plus a fascinating bonus - a CD ROM track with a slightly blurry display of Mozart's original autograph, whose pages can be synchronized with the music. The tangible evidence of Mozart's long struggle with this work, in contrast to his usual method of through-composing (writing his last opera in a mere 18 days), is a deeply poignant encounter - the eight-measure fragment of the Lacrymosa that trails off onto an otherwise blank page is believed to be the last thing he ever wrote as his life slipped away.

- H.C. Robbins Landon – Landon's main revisions are to restore Eybler's orchestration of the Sequenz (and to complete the portions he only sketched), consistent with his view that Eybler was an "infinitely superior" composer to Süssmayr.

Landon leaves alone the portions Süssmayr created, though, as he considers them to fit in well to Mozart's torso and to have stood the test of time. Roy Goodman and the Hanover Band (Nimbus, 1990) present a reading that's earnest, energetic and sharp, if just a bit cold and rigid, with constant tempo and dynamics and minimal vibrato. (Incidentally, "Band" isn't the modern pep rally or marching kind, but refers to the core set of musicians maintained by a royal court for which nearly all baroque and classical compositions were intended.) Bruno Weil and Tafelmusik (Sony Vivarte, 2000) use similarly reduced forces (but an all-boys' choir) for a swifter, more vivid and urgent account. Either straight-forward approach seems well suited to present Landon's intentions of respecting the hybrid score with minimal personal intrusion. Landon leaves alone the portions Süssmayr created, though, as he considers them to fit in well to Mozart's torso and to have stood the test of time. Roy Goodman and the Hanover Band (Nimbus, 1990) present a reading that's earnest, energetic and sharp, if just a bit cold and rigid, with constant tempo and dynamics and minimal vibrato. (Incidentally, "Band" isn't the modern pep rally or marching kind, but refers to the core set of musicians maintained by a royal court for which nearly all baroque and classical compositions were intended.) Bruno Weil and Tafelmusik (Sony Vivarte, 2000) use similarly reduced forces (but an all-boys' choir) for a swifter, more vivid and urgent account. Either straight-forward approach seems well suited to present Landon's intentions of respecting the hybrid score with minimal personal intrusion.

- Robert Levin - Levin's modifications of the Süssmayr score range from the subtle (graceful string figurations replacing the four-square rhythmic accompaniment in the Sanctus) to tripling the length of the Osanna

fugue at the end of the Benedictus and providing a jaunty new one to conclude the Sequenz (which Süssmayr had ended with a peremptory two-chord "Amen"), based on a 16-measure fragment by Mozart discovered only in the 1960s and believed to be intended for that purpose. All of this will be a surprise for those familiar with the traditional score, yet an intriguing revitalization for those to whom familiarity threatens to breed boredom. As heard by the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra and Chamber Chorus led by Donald Runnicles (Telarc, 2005) the voices dominate, as seems appropriate to Mozart's method of composition, which clearly conceived the work predominantly in vocal terms. Despite the rich sonority of full modern forces, fleet tempos (occasionally yielding to the demands of the text, as in the "salve me" ending of the Rex Tremendae) create an equally appropriate sense of urgency, given the circumstances of the composition. fugue at the end of the Benedictus and providing a jaunty new one to conclude the Sequenz (which Süssmayr had ended with a peremptory two-chord "Amen"), based on a 16-measure fragment by Mozart discovered only in the 1960s and believed to be intended for that purpose. All of this will be a surprise for those familiar with the traditional score, yet an intriguing revitalization for those to whom familiarity threatens to breed boredom. As heard by the Atlanta Symphony Orchestra and Chamber Chorus led by Donald Runnicles (Telarc, 2005) the voices dominate, as seems appropriate to Mozart's method of composition, which clearly conceived the work predominantly in vocal terms. Despite the rich sonority of full modern forces, fleet tempos (occasionally yielding to the demands of the text, as in the "salve me" ending of the Rex Tremendae) create an equally appropriate sense of urgency, given the circumstances of the composition.

- Richard Maunder – Consistent with his belief that, despite its familiarity, Süssmayr's work is unworthy to be heard aside Mozart, Maunder discards the Sanctus and Benedictus altogether, so the Agnus Dei leads directly into the reprise of Mozart's opening music for the Lux aeterna.

Based on internal evidence, though, he feels that the Agnus Dei is based on Mozart material and thus leaves it largely intact, excising some clumsy transitions. In lieu of Süssmayr's completion of Mozart's opening fragment of the Lacrymosa, Maunder provides a simpler, more calming vocal progression. Elsewhere, he rejects both Eybler's and Süssmayr's orchestrations of Mozart's vocals, although he concedes guidance from the former in crafting his own. He also concludes the Sequenz with a fugue based on the same Mozart fragment as Levin. The only available recording of the Maunder edition is by Christopher Hogwood and the Academy of Ancient Music (L'Oiseau-lyre, 1983), who conjecture a performance appropriate to Mozart's time. As Hogwood notes, Mozart did not know the source of the commission and so could not have had specific musical forces in mind. Yet, he takes his cue from Mozart's arrangement of Handel's Messiah for a 1789 performance, for which he had a choir of 12, the 4 soloists and 20 strings, to which are added the 2 basset horns, 2 oboes, 3 trombones, 2 trumpets, tympani and organ specified in the Requiem score. Hogwood further notes that while they were used for solos, women were never used in church choirs at the time, and so he combines male tenors and basses with boy sopranos and altos (who occasionally emerge for a solo). When combined with his players' original instruments and techniques of Mozart's time (including occasional ornaments and minimal vibrato), the thin and clear sound is both fascinating and instructive. Its added intimacy evokes the story, possibly true, that as his end approached Mozart sang portions of his Requiem with family and visitors. However, even with moderate tempos, the 43 minutes of Maunder's editing make for a very short premium-priced CD. Based on internal evidence, though, he feels that the Agnus Dei is based on Mozart material and thus leaves it largely intact, excising some clumsy transitions. In lieu of Süssmayr's completion of Mozart's opening fragment of the Lacrymosa, Maunder provides a simpler, more calming vocal progression. Elsewhere, he rejects both Eybler's and Süssmayr's orchestrations of Mozart's vocals, although he concedes guidance from the former in crafting his own. He also concludes the Sequenz with a fugue based on the same Mozart fragment as Levin. The only available recording of the Maunder edition is by Christopher Hogwood and the Academy of Ancient Music (L'Oiseau-lyre, 1983), who conjecture a performance appropriate to Mozart's time. As Hogwood notes, Mozart did not know the source of the commission and so could not have had specific musical forces in mind. Yet, he takes his cue from Mozart's arrangement of Handel's Messiah for a 1789 performance, for which he had a choir of 12, the 4 soloists and 20 strings, to which are added the 2 basset horns, 2 oboes, 3 trombones, 2 trumpets, tympani and organ specified in the Requiem score. Hogwood further notes that while they were used for solos, women were never used in church choirs at the time, and so he combines male tenors and basses with boy sopranos and altos (who occasionally emerge for a solo). When combined with his players' original instruments and techniques of Mozart's time (including occasional ornaments and minimal vibrato), the thin and clear sound is both fascinating and instructive. Its added intimacy evokes the story, possibly true, that as his end approached Mozart sang portions of his Requiem with family and visitors. However, even with moderate tempos, the 43 minutes of Maunder's editing make for a very short premium-priced CD.

- Duncan Druce – Motivating this, the most radical of all revisions, is Druce's conviction that Süssmayr's work ranges from competent to gauche, "but never with the appositeness, grace and imagination we expect throughout Mozart's compositions." But rather than reject it outright, Druce takes Süssmayr's starting material and reconceives it, as he feels "a competent eighteenth-century composer sympathetic to [Mozart's] style and reasonably knowledgeable as to his methods" might have done.

His result often departs from the score we have come to know, but with fascinating results, emphasizing creative orchestral passages into which the voices are nestled. Thus, the Lacrymosa is restructured into two parallel halves with a soothing instrumental interlude and postlude that slams right into the "Amen" fugue, based on the same Mozart fragment as Levin and Maunder but nearly twice as long and mightier in scope, enriching the bounding theme with dramatic turns and even a grand pause. Both the Osanna (which Druce finds "perfunctory") and Benedictus ("harmonically static") begin with Süssmayr's themes but then depart entirely, the latter into a delightful five-minute fantasia. After an extended instrumental prologue, the repetition of Mozart's opening music returns for the Lux aeterna, which seems a comfortable and apt conclusion after a longer and more adventurous journey than we are accustomed. The sole recording of the Druce edition is by Roger Norrington and the London Classical Players and Schütz Choir (EMI, 1991, reissued on Virgin). Using authentic instruments but larger forces than Hogwood (29 strings, 33 singers), Norrington presents a richer vision that leans toward the romantic side of Mozart, rather than Hogwood's cooler baroque sensibility. The Norrington CD frames the Requiem with fitting short pieces - a prelude of Mozart's 1785 Masonic Funeral Ode and a postlude of his simple choral motet Ave verum corpus, an exquisite, ethereal jewel written in June 1791, possibly just as he received that mysterious final commission. His result often departs from the score we have come to know, but with fascinating results, emphasizing creative orchestral passages into which the voices are nestled. Thus, the Lacrymosa is restructured into two parallel halves with a soothing instrumental interlude and postlude that slams right into the "Amen" fugue, based on the same Mozart fragment as Levin and Maunder but nearly twice as long and mightier in scope, enriching the bounding theme with dramatic turns and even a grand pause. Both the Osanna (which Druce finds "perfunctory") and Benedictus ("harmonically static") begin with Süssmayr's themes but then depart entirely, the latter into a delightful five-minute fantasia. After an extended instrumental prologue, the repetition of Mozart's opening music returns for the Lux aeterna, which seems a comfortable and apt conclusion after a longer and more adventurous journey than we are accustomed. The sole recording of the Druce edition is by Roger Norrington and the London Classical Players and Schütz Choir (EMI, 1991, reissued on Virgin). Using authentic instruments but larger forces than Hogwood (29 strings, 33 singers), Norrington presents a richer vision that leans toward the romantic side of Mozart, rather than Hogwood's cooler baroque sensibility. The Norrington CD frames the Requiem with fitting short pieces - a prelude of Mozart's 1785 Masonic Funeral Ode and a postlude of his simple choral motet Ave verum corpus, an exquisite, ethereal jewel written in June 1791, possibly just as he received that mysterious final commission.

More detailed information can be found in the editors' notes to the CDs and in numerous Mozart biographies (but only the ones by serious authors - far too many of the others perpetuate myths). I also recommend Michael Steinberg's Choral Masterworks: A Listener's Guide (Oxford, 2005), H.C.Robbins Landon's 1791: Mozart's Last Year (Schirmer, 1988), which places the work in the context of the other challenges faced by the composer toward the end of his life, and Richard Maunder's Mozart's Requiem: On Preparing a New Edition (Oxford, 1988), which provides a thorough scholarly appraisal of the work and its sources, together with a compelling defense of the author's approach and choices in compiling his modern edition of the work.

Copyright 2006 by Peter Gutmann

|