|

|

Beethoven's Grosse Fuge demands attention as the most advanced work of our greatest composer. In this article, we review the development of the fugue as a musical genre, place the Grosse Fuge in the context of Beethoven's late quartets to which he devoted his final years, examine its remarkable structure, consider its early performances, and then survey the often-heard full string orchestral adaptations and quartet recordings. Finally, we suggest some sources for further information.

|

|

As the most progressive work of the greatest composer in the history of Western music, Ludwig van Beethoven's Grosse Fuge demands vast attention.  Yet it attracts far more respect than genuine affection. Yet it attracts far more respect than genuine affection.

Even the composer's most ardent enthusiasts have had some awfully harsh things to say about the Grosse Fuge. Thus, Alexander Wheelock Thayer, who devoted a half-century to researching a comprehensive biography of the composer: "It will scarcely ever touch the heart." Paul Bekker: "All emotion is stifled." Hugo Liechtentrift: "Impersonal, hostile objectivity." Daniel Gregory Mason: "Long, complicated and through many hearings repellent if not unintelligible." Joseph Kerman: "[It] stands out as the most problematic single work in Beethoven's output and … doubtless in the entire literature of music." Yet Ludwig Misch asserts: "All that is lacking is to be understood." Some attribute the dreadful reputation of the Grosse Fuge to its formidable technical challenges. Harold Truscott contends that its logic, beauty and directness of expression are hidden by substandard performances. Robert Haven Schauffler adds: "Its extraordinarily crabbed and cruel technical difficulties usually make it sound dry and dully ponderous in performance." Yet again Thayer: "[Beethoven's] affections were fixed on the higher and purer regions of chamber music, the form which represents chaste ideals, lofty imagination, profound learning, which extracts a muted sympathy between composer, performer and listener."

Just what is a fugue? The entries in a dozen dictionaries and music encyclopedias range from a simple sentence to several pages and reveal no common definition nor even much consensus. The recurrent elements cluster around successive imitative entries in different voices of one or more subjects that are contrapuntally developed. Other useful factors include "continuous interweaving" (Mirriam-Webster Dictionary), "bringing each [entry or voice] in turn into special prominence … based on the principle of equality of the parts" (Baker's Student Encyclopedia of Music) and "distinct sections or stages of development" (Webster's Unabridged Dictionary). Just what is a fugue? The entries in a dozen dictionaries and music encyclopedias range from a simple sentence to several pages and reveal no common definition nor even much consensus. The recurrent elements cluster around successive imitative entries in different voices of one or more subjects that are contrapuntally developed. Other useful factors include "continuous interweaving" (Mirriam-Webster Dictionary), "bringing each [entry or voice] in turn into special prominence … based on the principle of equality of the parts" (Baker's Student Encyclopedia of Music) and "distinct sections or stages of development" (Webster's Unabridged Dictionary).

Literally meaning "flight,"

Beethoven in 1824

Chalk drawing by Stephan Decker |

the fugue had its roots in sung canons or rounds in which a single theme is repeated at regular intervals (think of "Row, Row, Row Your Boat" or "Three Blind Mice"). Generally deemed to have reached its apex of development in the first half of the 18th century with Bach, who found its unity within variety to be the perfect symbol of the omnipresence of God, fugues have cropped up in the work of nearly every major composer ever since. Indeed, Beethoven himself became so enamored with the form that he included a fugue in nearly every one of his major late works, including the final pieces he wrote in favorite genres – his last cello sonata (Op. 102/2), piano sonata (op. 111), symphony (#9, Op. 125), variations (Diabelli, Op. 120), mass (Missa Solemnis, Op. 123), overture (Consecration of the House, Op. 124) – and quartets.

Scholars continue to debate Beethoven's use of the form in his Grosse Fuge. Drawing an analogy to Bach's final work, Warren Kirkendale regards it as Beethoven's Art of Fugue, a theoretical compendium displaying all the known devices and exploring all the variations to which a fugue subject is susceptible. Kerman, for one, disputes this, instead viewing the Grosse Fuge as not probing the limits of contrapuntal technique at all, but rather presenting a freer treatment that extends the range of a fugue beyond its traditional bounds into new styles. Mason agrees, saluting the hybrid nature of the Grosse Fuge and calling it a synthesis of styles and forms, melding fugues with variations. Beethoven himself probably would have agreed with Kerman and Mason, as he had expressed his intentions clearly: "In my student days I wrote dozens of fugues. But the fancy also wishes to exert its privileges and today a new and really practical element must be introduced into the old and traditional forms." Thus, Beethoven subtitled the Grosse Fuge: "tantôt libre, tantôt recherchée" ("somewhat free, somewhat scholarly"). He explained to his friend Karl Holz: "You will find a new manner of voice treatment and – thank God – there is less lack of fancy than ever before."

The question remains as to why Beethoven seized upon this archaic form (albeit leavened with his "fancy") at all. Robert Winter and Robert Martin note that, after a decade of slackening public interest in his work, Beethoven had just received huge acclaim for his new large-scale choral and symphonic works (the Missa Solemnis and "Choral" Symphony), yet he seemingly declined to pursue further success along those lines, turning instead to string quartets – the most intimate of all genres which held no hope of public performance – to which he devoted the rest of his life, thus shunning practicality for idealism. While Beethoven's sketch books suggest that he was planning further major works, including a tenth symphony, a treatment of Faust, an overture on B-A-C-H and a new piano sonata, none was ever realized. Perhaps the answer is that after a lifetime of toiling to fulfill the orders of patrons and please the public, Beethoven no longer cared to satisfy anyone but himself. Indeed, Truscott sees these works as a continuation of Beethoven's seclusion fostered by his deafness, a withdrawal from the world to achieve a direct communion between himself and his Creator.

The Grosse Fuge was never meant to stand on its own, but rather was conceived as the finale of Beethoven's 1825 String Quartet in B-flat, Op. 130. Shortly before, Beethoven had returned to the string quartet after a hiatus of over a dozen years. The Grosse Fuge was never meant to stand on its own, but rather was conceived as the finale of Beethoven's 1825 String Quartet in B-flat, Op. 130. Shortly before, Beethoven had returned to the string quartet after a hiatus of over a dozen years.  In 1800 he had produced a set of six (his Opus 18) that reflected the same foundation in Haydn classicism as his first symphony and first two piano concertos of the same era; another three (Op. 59) in 1806, solidly grounded in his "middle period" aesthetic of maturity and assurance; and two more (op. 74 and 95) in 1809-10, the latter of which seems poised on the brink of a transition. Truscott notes that Beethoven had sketched more quartets as early as 1821 but was awaiting the stimulus of a commission.

As recounted by Thayer, that came from Prince Nikolaus Galitzin of St. Petersburg, who ordered "one or two or three quartets for which I will be glad to pay you what you think proper." Beethoven agreed to 50 ducats each. Sadly, after an initial payment the Prince reneged, even after Beethoven sent a courier to remind him of his obligation. (The debt was finally paid, but not until 1852 and then only to Beethoven's heirs. Lev Ginsburg researched the matter and concluded that the Prince did not proceed in bad faith but had suffered many personal setbacks in the interim.) In 1800 he had produced a set of six (his Opus 18) that reflected the same foundation in Haydn classicism as his first symphony and first two piano concertos of the same era; another three (Op. 59) in 1806, solidly grounded in his "middle period" aesthetic of maturity and assurance; and two more (op. 74 and 95) in 1809-10, the latter of which seems poised on the brink of a transition. Truscott notes that Beethoven had sketched more quartets as early as 1821 but was awaiting the stimulus of a commission.

As recounted by Thayer, that came from Prince Nikolaus Galitzin of St. Petersburg, who ordered "one or two or three quartets for which I will be glad to pay you what you think proper." Beethoven agreed to 50 ducats each. Sadly, after an initial payment the Prince reneged, even after Beethoven sent a courier to remind him of his obligation. (The debt was finally paid, but not until 1852 and then only to Beethoven's heirs. Lev Ginsburg researched the matter and concluded that the Prince did not proceed in bad faith but had suffered many personal setbacks in the interim.)

The three quartets that Beethoven produced for Galitzin were of unprecedented length and complexity.  Burnett Jones views them as "a great interrelated triptych bound together spiritually by an internal creative process of the most comprehensive and far-reaching kind, and musically by a single thematic motif." The first, now known as his Quartet # 12 in E-Flat Major, Op. 127, is the most conventional of the three, comprised of the traditional four movements (allegro, adagio, scherzo, finale), although the second movement, nearly as long as the others combined, stretches the structure through its sheer length and sustained mood. Next came the Quartet # 15 in a minor, Op. 132 (the numbering and opus due to its later publication), which expands the scope to five movements, centered around an extraordinary, deeply spiritual, prolonged molto adagio (inscribed "Hymn of thanks to God from a convalescent") that surrounds its measured stability with impassioned outer movements and spirited dances. Burnett Jones views them as "a great interrelated triptych bound together spiritually by an internal creative process of the most comprehensive and far-reaching kind, and musically by a single thematic motif." The first, now known as his Quartet # 12 in E-Flat Major, Op. 127, is the most conventional of the three, comprised of the traditional four movements (allegro, adagio, scherzo, finale), although the second movement, nearly as long as the others combined, stretches the structure through its sheer length and sustained mood. Next came the Quartet # 15 in a minor, Op. 132 (the numbering and opus due to its later publication), which expands the scope to five movements, centered around an extraordinary, deeply spiritual, prolonged molto adagio (inscribed "Hymn of thanks to God from a convalescent") that surrounds its measured stability with impassioned outer movements and spirited dances.

But Beethoven saved his most startling innovations for last. The final Galitzin quartet, # 13 in B-flat Major, Op. 130, wrenches a listener amid sharply differentiated moods, often mere seconds apart, heralded by a restless start-and-stop first movement. The second, a terse two-minute presto, bristles with nervous energy; the third is a curious andante poco scherzando, whose fundamental pastoral feeling pulses with a constant undercurrent of activity; and the fourth, labeled "alla danza tedesca" (literally "like a German dance," but more figuratively in the manner of an Allemande, or quick waltz) boasts a gorgeous melody that veers toward the cloying and saccharine. Next comes an exquisitely heartfelt cavatina, blending the rich instrumental lines with patient evolution; reportedly, Beethoven would weep just thinking about it and told Holz that nothing he had written so moved him. The cavatina ends on a lingering wisp of serenity.

The sixth and final movement is the Grosse Fuge, which, despite its formal title, snaps the mood even more drastically. Neither a salute to the past nor a summary of existing art, rather it is a bold exploration into unknown musical territory. The sixth and final movement is the Grosse Fuge, which, despite its formal title, snaps the mood even more drastically. Neither a salute to the past nor a summary of existing art, rather it is a bold exploration into unknown musical territory.

The Fugue Variants Presented in the "Overtura"

The first bold unison variant

The second variant in triple time

The third, straightforward variant

The tail of the third variant

The tense fourth variant |

This is apparent from the very outset, a startling one-minute "Overtura" that Kerman aptly characterizes as "not an introduction but a table of contents [that] hurls all the thematic variations at the listener's head like a handful of rocks." It begins with a unison open G (extending the final note of the cavatina) spanning three octaves and then, separated by dramatic pauses, a bold unison accelerating statement of the basic theme that ends on a brief trill; a repeated faster variant in triple time; a slower four-square rendition leading to a pastoral cascade of gentle 16th notes; and finally an even softer account that separates each tentative note with tense expectation.

Not only has Beethoven given us the building blocks for all that is to come, but the score of the overture reveals far more than meets the ear: in addition to ranges of accents and tempos, he has migrated smoothly down the circle of fifths from G (where the cavatina ended) to B-flat (where the fugue proper is about to begin), gradually hushed the volume from fortissimo to pianissimo (comprising the extreme ends of the dynamic range at the time), led us from full ensemble, through accompanied melody to bare solo (thus displaying the full realm of textures possible in a quartet); and destroyed all known notions of standard rhythm (the second variant sounds as if its downbeats fall in the middle of each bar, the third variant begins on the weak second beat, and the fourth variant starts on the even weaker fourth beat). But even that's not all – consider the notation of the last variant, written as joined identical eighth notes rather than using quarter notes. Clearly Beethoven was trying to convey something here, but to this day no one definitively has suggested just what. Perhaps there is no musical or interpretive point at all, other than to disrupt conventional thinking in preparation for what is to come.

With such an unruly and sweeping introduction, Beethoven promises a wildly eccentric movement, and he delivers immediately with the first fugue – an abrasive, jerky theme to which the final variant of the overture serves as a dissonant counter-subject.

The beginning of the first fugue |

The notation remains confusing – notice the bizarre placement of the bar lines one beat beyond where the downbeats are felt. Beethoven adds further complexity by separately marking each set of tied notes with ff (fortissimo), f (forte) or sf (sforzando), thus suggesting microscopic gradations within a consistently loud volume. Mason aptly describes the first fugue "as dry and ungrateful for the ear as it is wearisome for the mind," and indeed it continues unabated for a solid four minutes, its relentless strident monotony only barely relieved by triplet and syncopated figures. Next comes a second fugue that is more subtly confounding – it's largely in the remote and rather depressed key of G-flat, yet based on the flowing lyrical third variant of the introduction. From that point, the formal structure turns increasingly "fanciful." Mason breaks it down into a sort of scherzo (a fantasy on the triplet second variant of the overture) that only flirts at becoming a proper fugue, a recherché section in which fugal devices, notably augmentation (stretching out the main theme), compete for attention without assuming their role in an actual fugue, and a development in which the variants of the overture struggle for dominance. Mason further notes that while they give an impression of diffuse non-sequiturs the major sections evoke the movements of a classical symphony. Yet, attempts to impose conventional rationality and force the Grosse Fuge into traditional molds seem futile; rather, Beethoven has left us something far more valuable – a glimpse into the inventive thoughts of the most brilliant thinker in our musical history.

And then comes the mind-boggling coda, which brackets the Grosse Fuge with a gesture even more radical than the overture, which it superficially recalls. We first are plunged back into the opening materials, but now even more fragmented – the first brittle fugal theme sputters after only 12 notes, and the lyric variant stalls after a mere 16. (While this could be analogized to the finale of the Ninth Symphony in which earlier themes are recalled and rejected, here Beethoven provides no thoughtful cello commentary coalescing into a triumphant "Ode to Joy," but rather only the stony silence of empty pauses.) Then comes a return of the hyper-dramatic opening statement, but now unaccelerated and prolonged, with the final trill meandering ominously among the instruments. The suspense is leavened by shards of the first fugal theme, but this time bewilderingly transformed into a sweet, soft outline of its overall shape, shorn of its former jagged rhythm and placed high in the first violin so as to hover over the proceedings with an air of expectancy. Harmonized by the fundamental theme and propelled by chugging viola triplets, this new seed gathers steam and builds to a quick, rousing, affirmative climax solidly grounded in the home key of B-flat.

Truscott cautions against viewing Beethoven's late quartets, and especially the Grosse Fuge, as a farewell gesture, much less his final artistic statement, since he was in fair health (for him) and had no way of knowing that his life would soon end. Indeed, in a literal sense the Grosse Fuge was not Beethoven's last word. Following the three Galitzin quartets, Beethoven would conclude his life's work with two more. The Quartet # 14 in C-sharp minor, Op. 131, often cited as his greatest, bursts even further through established formal boundaries with seven movements, its predominant mood set not only by the remote key but by the patient unwinding of a long opening fugal adagio.

Quartet # 16 – opening of the fourth movement

"Must it be?" – "It must be!" |

The long central slow movement meanders through seven distinctive but connected sections for an impression of a stream of consciousness and a continuous emotional journey, a feeling fostered by abutting the movements together without pause. And then, as if once again to thwart expectations, in his final quartet, #16 in F minor, Op. 135, Beethoven reverts not only to classical form and the traditional brevity and scope of four movements but, with the exception of a heartfelt (but relatively succinct) lento assai, harks back to the carefree bounding spirit of Haydn, recalling his first foray into quartets three decades before. (Here, we should note that many commentators impose considerable metaphysical weight upon Beethoven's last quartet, citing the final movement, which opens with a portentious phrase labelled by Beethoven "Must it be?" and then its jaunty inversion, labelled: "It must be." We often read that this was Beethoven's profound attempt to wrestle with the fundamental question of existence and then to reconcile himself to the demands of life. Yet Thayer reveals that it was nothing of the sort, but rather the punch line of a joke, to which Beethoven had previously written a canon.)

Yet, surely the end of the Grosse Fuge contains a deeply personal valedictory message. After taking a simplistic and unattractive theme through the extraordinary paces of his imagination, Beethoven provides a final audience-pleasing fillip, but he dares us not to believe it for a moment, as such a brief gesture cannot possibly serve as a genuinely satisfying conclusion after such an outpouring of profound creativity. (On a larger scale, Beethoven had ended his 1823 Missa Solemnis in much the same way, with a perfunctory smile after shoving aside his "Agnus Dei" to invoke the horrors of war through a militaristic fugue. There, too, the effect is to end with a superficial affirmation that utterly fails to lighten the overall mood following the impact of all the profound trepidation that came before.) Rather, Beethoven has laid out the pieces of a complex puzzle in the overture, shown us a few possible solutions and then sets out the components once again in the coda, shuffles his cards, hands them to us and challenges us to embark on our own creative quest. Having pushed music as far as he could to the farthest reaches of his own extraordinary invention, Beethoven simply leaves us his materials, shrugs and walks off, daring us to expand music yet further into realms where not even he was prepared to venture.

The Grosse Fuge is the visionary gesture of a supreme artist and the ultimate legacy of a fully confident master, fiercely proud of the doors he has opened and the paths he has blazed, yet humble enough to know when to lay down his pen and stand aside to make way for the explorations and discoveries of new generations.

The premiere performance of Op. 130 (and the only one during Beethoven's lifetime) was given on March 21, 1826 by a quartet organized by Ignaz Schuppanzigh, who had taught Beethoven thirty years earlier, who reportedly was the first musician in history to devote himself to quartet playing, and who constantly inspired Beethoven and advocated his music. The composer did not attend but was in a nearby tavern. Thayer reports that Beethoven was greatly upset to learn that the simple second and fourth dance movements were thunderously applauded and repeated, but not the fugue (nor even his beloved cavatina), and cursed the audience as "cattle and asses." The premiere performance of Op. 130 (and the only one during Beethoven's lifetime) was given on March 21, 1826 by a quartet organized by Ignaz Schuppanzigh, who had taught Beethoven thirty years earlier, who reportedly was the first musician in history to devote himself to quartet playing, and who constantly inspired Beethoven and advocated his music. The composer did not attend but was in a nearby tavern. Thayer reports that Beethoven was greatly upset to learn that the simple second and fourth dance movements were thunderously applauded and repeated, but not the fugue (nor even his beloved cavatina), and cursed the audience as "cattle and asses."

Title page of Artaria's first edition of the Grosse Fuge |

Beethoven's friends argued that the finale had not been understood and that this objection would disappear with repeated hearings. Others, though, urged him to provide a more palatable substitute. Artaria, who had purchased the publication rights, presented a practical compromise, offering to issue the fugue separately if Beethoven would write a new finale for the quartet. Surprisingly for such an inflexible man, Beethoven reluctantly agreed. It would be the last piece he ever wrote.

The new finale certainly serves as relief from the gravity and depth of the Grosse Fuge, but not necessarily for the better. Maynard Solomon views it as a cathartic return to earth and normalcy after the prior flights. Michael Steinberg feels that it shifts the emotional weight of the quartet to the cavatina. Bekker wrote that it fails to gather up the trails leading to the fugue which Beethoven scattered so skillfully throughout the earlier movements. Kerman quipped that while the Grosse Fuge "runs the danger of trivializing the experience of the other movements, the new finale runs the danger of seeming trivial itself." But Truscott, for one, vigorously disputes that view, asserting that it is only superficially easier to listen to and understand but rather is subtler, condensing equally immense technical problems to a smaller scale: "Any quartet which believes that it is an easier movement than the fugue is in no position to tackle it." Yet the ear is not so readily convinced – the new finale clearly feels slighter and its thin material can barely sustain its repetitious ten-minute length. While most commentators insist that the Grosse Fuge forms an integral part of the quartet and thus should be restored to its proper place, nowadays the quartet usually is played with the substitute finale, although recordings often add the Grosse Fuge as a supplement.

J. W. N. Sullivan asserted that Beethoven "knew exactly what he had done in the original version of this quartet and he knew that the world would insist upon hearing it when it was ripe for it."

Ignaz Schuppanzigh |

Yet, while the popularity of Beethoven's work soared, both during his life and after, the Grosse Fuge was largely ignored. Indeed, as late as 1889, Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians lamented that "One has no means of judging it, as it is never played." (But surely the author was sufficiently musically literate to have judged it by reading the score!) At first, much of the problem was the evolving status of quartets in general. As traced by Robert Winter, for the first half of the 19th century there were no established professional quartets but only pick-up groups assembled for private and occasional public concert series, for which the Haydn, Mozart and early Beethoven quartets formed their core repertoire. In 1835 and 1846, societies were formed in Paris and London for the purpose of studying and playing the late Beethoven quartets (albeit in private). The first public performance of the Grosse Fuge in Beethoven's home town of Vienna came only in 1859 (to "resounding bravos" according to a review).

Roger Fiske credits the late Beethoven quartets as both reflecting and driving a fundamental change in which chamber music would no longer be written for casual performers but rather for listeners, and would come to be played by permanent professional quartets in public concerts rather than by amateurs and pick-up groups in private homes of wealthy patrons. Even so, Fiske notes that full appreciation was suppressed due to a persistent faith in progress, which viewed the work of the past as inherently inferior to all that succeeded it. In any event, nowadays most commentators concur that the late Beethoven quartets represent the peak of accomplishment in the genre that has never been equaled (although generations later Bartok and Shostakovich perhaps would come closest).

Two adaptations shed special light on the original. Following the practice of the time, Artaria planned to publish a piano reduction, in this case for four hands, which he commissioned from Anton Halm. (These arrangements were the forebears of recordings, enabling music lovers to perform a new work at home with forces on hand – anyone with even a smattering of culture played the piano, and it was easier to grab a friend or family member for a piano duet than to assemble a full string quartet.) Beethoven, though, rejected Halm's draft for having redistributed the parts for the convenience of the hands rather than preserving the integrity of the individual lines even when they crossed, and then produced his own version (for which he demanded an additional fee), which was published posthumously in May 1827 as his Opus 134. (An interesting sidelight – Beethoven's autograph surfaced only in 2005 in a Philadelphia seminary library and was auctioned that November by Sotheby's for nearly $2 million.) In the notes to his Nonesuch recording with Ursula Oppens, Paul Jacobs observed that Beethoven's rendering was indigenous to the piano and extended the range both upward in the treble and downward in the bass, yet the result remained so complex as to be unmanageable on a single keyboard, so Jacobs and Oppens each played separate pianos. In any event, while the content may all be there, the piano reduction falls far short of the string original in presenting the sustained notes, differentiating the textures and conveying the gripping sense of tense exertion. Two adaptations shed special light on the original. Following the practice of the time, Artaria planned to publish a piano reduction, in this case for four hands, which he commissioned from Anton Halm. (These arrangements were the forebears of recordings, enabling music lovers to perform a new work at home with forces on hand – anyone with even a smattering of culture played the piano, and it was easier to grab a friend or family member for a piano duet than to assemble a full string quartet.) Beethoven, though, rejected Halm's draft for having redistributed the parts for the convenience of the hands rather than preserving the integrity of the individual lines even when they crossed, and then produced his own version (for which he demanded an additional fee), which was published posthumously in May 1827 as his Opus 134. (An interesting sidelight – Beethoven's autograph surfaced only in 2005 in a Philadelphia seminary library and was auctioned that November by Sotheby's for nearly $2 million.) In the notes to his Nonesuch recording with Ursula Oppens, Paul Jacobs observed that Beethoven's rendering was indigenous to the piano and extended the range both upward in the treble and downward in the bass, yet the result remained so complex as to be unmanageable on a single keyboard, so Jacobs and Oppens each played separate pianos. In any event, while the content may all be there, the piano reduction falls far short of the string original in presenting the sustained notes, differentiating the textures and conveying the gripping sense of tense exertion.

That problem is partly overcome – yet, in a sense, exacerbated – by numerous versions for full string orchestra, of which the first appears to have been by Hans von Bülow in the 1880s and the most commonly-heard is by composer/conductor Felix Weingartner. (Many of the late quartets received similar treatment from Mahler, Furtwängler, Mitropoulos and even Toscanini; Leonard Bernstein left us deeply committed readings of Opp. 131 and 135 with the Vienna Philharmonic [on DG CDs].)  With each part played by massed strings, and their depth anchored by the addition of double basses, the sheer volume of sound is clearly enhanced. Mason asserted that the Grosse Fuge is too strong for the intimate sincerity of chamber music and that it became intelligible and expressive when enlarged for string orchestra. Yet, no matter how cleanly the players articulate, the sheer visceral impact of the original inevitably is smoothed over and compromised. This is apparent from the very outset with the transcription of the overture. As already noted, the overture functions not only to introduce the variants of the theme that Beethoven will exploit throughout, but so much more – the full realms of dynamics, textures and accents, none of which a full complement of strings can convey anywhere near as effectively as a quartet. Above all else, even beyond these specific qualities, the most severe loss is the sheer sense of struggle generated by individuals straining to project ideas beyond the ordinary realm of a mere four players. While Beethoven's conception may have been universal, he tailored his late work to take full advantage of the capacities – and, equally important, the limitations – of a string quartet. As the unidentified commentator to the Aeolian Quartet LP box noted, "Beethoven seems to be striving after some almost unplayable, almost unattainable, almost metaphysical end." Perhaps the "point" of the Grosse Fuge is that it was conceived as an abstraction that intentionally lay beyond the ability of mortal musicians and their instruments to fully realize. With each part played by massed strings, and their depth anchored by the addition of double basses, the sheer volume of sound is clearly enhanced. Mason asserted that the Grosse Fuge is too strong for the intimate sincerity of chamber music and that it became intelligible and expressive when enlarged for string orchestra. Yet, no matter how cleanly the players articulate, the sheer visceral impact of the original inevitably is smoothed over and compromised. This is apparent from the very outset with the transcription of the overture. As already noted, the overture functions not only to introduce the variants of the theme that Beethoven will exploit throughout, but so much more – the full realms of dynamics, textures and accents, none of which a full complement of strings can convey anywhere near as effectively as a quartet. Above all else, even beyond these specific qualities, the most severe loss is the sheer sense of struggle generated by individuals straining to project ideas beyond the ordinary realm of a mere four players. While Beethoven's conception may have been universal, he tailored his late work to take full advantage of the capacities – and, equally important, the limitations – of a string quartet. As the unidentified commentator to the Aeolian Quartet LP box noted, "Beethoven seems to be striving after some almost unplayable, almost unattainable, almost metaphysical end." Perhaps the "point" of the Grosse Fuge is that it was conceived as an abstraction that intentionally lay beyond the ability of mortal musicians and their instruments to fully realize.

Among recordings of the string orchestra version, the first, by the Busch Chamber Players in 1941 (Columbia 78s; Biddulph CD), negotiates the gap between the astringency of the original and the heft of the adaptation by paring forces to what sounds like only a few players per part. After a somewhat drowsy start, the young musicians cohere with hair-trigger precision. Yet, although most performances startle with the harsh impact of the first fugue (after which the rest can seem wearying), the Busch players build toward (and then away from) the central section which emerges with uncommon speed and intensity, abetted by a somewhat strident recording.

Subsequent fleshed-out versions can be divided into those adhering to chamber proportions and those going all the way with a full orchestral string section.  A seemingly reasonable assumption that the former are apt to be more responsive and lean is belied by a 1952 version by Karl Münchinger and the Stuttgart Chamber Orchestra (London LP), which, a cover photo shows, assigns only three players to each part (plus a double bass) – they succeed in integrating the sections, but only through persistent monotony, and Beethoven's fanciful elements are nowhere to be found amid the strict formality and consistent absence of any expression or variation. Thus, throughout the soft moderato section where the score clearly specifies slurred groups, each note is played detached and rigid, the con brio 6/8 section is bereft of any sense of playfulness, and even the bounding trills sound purely academic. On the other hand, the Winograd String Orchestra, named for and led by cellist Arthur Winograd, a founder of the Juilliard Quartet (which included the Grosse Fuge in its first public concert) (MGM LP, 1950s), also achieves remarkable unity, but in a far more exciting way. A seemingly reasonable assumption that the former are apt to be more responsive and lean is belied by a 1952 version by Karl Münchinger and the Stuttgart Chamber Orchestra (London LP), which, a cover photo shows, assigns only three players to each part (plus a double bass) – they succeed in integrating the sections, but only through persistent monotony, and Beethoven's fanciful elements are nowhere to be found amid the strict formality and consistent absence of any expression or variation. Thus, throughout the soft moderato section where the score clearly specifies slurred groups, each note is played detached and rigid, the con brio 6/8 section is bereft of any sense of playfulness, and even the bounding trills sound purely academic. On the other hand, the Winograd String Orchestra, named for and led by cellist Arthur Winograd, a founder of the Juilliard Quartet (which included the Grosse Fuge in its first public concert) (MGM LP, 1950s), also achieves remarkable unity, but in a far more exciting way.  Shaving a mere minute or so from the standard pacing of 16½, the Winograd players amaze with what a vital tempo, modest inflection and attentive phrasing can do. Their constant drive creates an inevitability that pulls us along to bridge the many gaps in the continuity of the score and suggests more of a youthful adventure of discovery than autumnal rumination. The 2-LP set included as a logical companion a string realization of Bach's Art of the Fugue. Shaving a mere minute or so from the standard pacing of 16½, the Winograd players amaze with what a vital tempo, modest inflection and attentive phrasing can do. Their constant drive creates an inevitability that pulls us along to bridge the many gaps in the continuity of the score and suggests more of a youthful adventure of discovery than autumnal rumination. The 2-LP set included as a logical companion a string realization of Bach's Art of the Fugue.

Diverse interpretive approaches are also taken in two of the most renown full orchestral recordings. Otto Klemperer and the Philharmonia Orchestra strings (EMI, 1956) are straightforward and attentive to detail. Klemperer also relieves any sense of oppressive massed sound by clarifying the texture in a way that boasts historical validity. Throughout the work, Beethoven took great pains to mischievously divide the lead role between the two violins, rather than relegate the second seat player to its traditional role of being a second fiddle, so to speak. By separating his first and second violins to the left and right of the podium (and hence of the recorded stereo soundstage), Klemperer creates an effective aural analog to the visual clues of seeing a quartet in performance, as Beethoven surely intended.  While the stereo "ping pong" effect of trills and other phrases careening back and forth between the two violin parts belies a concert-hall experience, it serves as a brilliant and highly effective means of restoring the wonder of Beethoven's scoring, which too often is lost by the standard orchestral seating (and in all monaural recordings) in which the two violin parts can barely be distinguished. (In that regard, let's recall how upset Beethoven was at the Halm piano transcription for failing to sufficiently differentiate the original parts.) While the stereo "ping pong" effect of trills and other phrases careening back and forth between the two violin parts belies a concert-hall experience, it serves as a brilliant and highly effective means of restoring the wonder of Beethoven's scoring, which too often is lost by the standard orchestral seating (and in all monaural recordings) in which the two violin parts can barely be distinguished. (In that regard, let's recall how upset Beethoven was at the Halm piano transcription for failing to sufficiently differentiate the original parts.)

The Grosse Fuge would seem to naturally resonate within the deep philosophical soul of Wilhelm Furtwängler, and indeed his 1954 concert recording with the Vienna Philharmonic (Music & Arts CD) is profoundly personal, balancing and shaping Beethoven's materials to create a sort of narrative that speaks of weighty yet intangible things. Through careful phrasing, graduated dynamics and occasional tempo alterations Furtwängler creates subtle drama to underline the structure with suspense and a variety of expressive infusion. Even the diffuse coda manages to hang together and make intellectual and emotional sense, in large part due to the careful preparation and weighting of each part, and the very end manages to emerge as a convincing conclusion, as it gathers cumulative strength to culminate in a persuasive note of catharsis.

But when all is said and done, whether heard alone or in the context of the full Op. 131, the Grosse Fuge is ineluctably conceived for string quartet. Winter and Martin uphold the aptness of the format as an ideal confluence of two crucial factors – it exploits the intimacy of the most expressive family of instruments and comprises the number of voices needed for a four-voice chord, which they consider the richest texture that the ear can easily follow. Winter further notes that Beethoven was a passable violinist and thus understood the idiomatic characteristics of the string family. In a sense, we've become spoiled by the extraordinary rise in the quality of string quartet playing since Beethoven's time, Yet the high degree of polish and effortless clearance of technical hurdles in so many modern recordings defeats the sheer rough edginess that Beethoven built into the piece and that he must have assumed would be an inherent part of any performance. So despite the clarity and sonic pleasure that smooth, note-perfect recordings afford, I generally dismiss them as falsifying the composer's intentions and violating the idiomatic essence of the Grosse Fuge. But when all is said and done, whether heard alone or in the context of the full Op. 131, the Grosse Fuge is ineluctably conceived for string quartet. Winter and Martin uphold the aptness of the format as an ideal confluence of two crucial factors – it exploits the intimacy of the most expressive family of instruments and comprises the number of voices needed for a four-voice chord, which they consider the richest texture that the ear can easily follow. Winter further notes that Beethoven was a passable violinist and thus understood the idiomatic characteristics of the string family. In a sense, we've become spoiled by the extraordinary rise in the quality of string quartet playing since Beethoven's time, Yet the high degree of polish and effortless clearance of technical hurdles in so many modern recordings defeats the sheer rough edginess that Beethoven built into the piece and that he must have assumed would be an inherent part of any performance. So despite the clarity and sonic pleasure that smooth, note-perfect recordings afford, I generally dismiss them as falsifying the composer's intentions and violating the idiomatic essence of the Grosse Fuge.

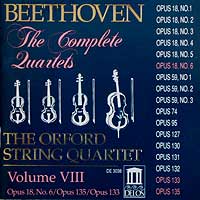

Many recordings of the original version are appended to cycles of the complete Beethoven quartets (or to sets of the late ones).  While this tends to limit the choices for collectors on a budget who seek only the Grosse Fuge, it serves to place the work in appropriate context as the culmination of Beethoven's development of the genre throughout the key stages of his incomparable career. While this tends to limit the choices for collectors on a budget who seek only the Grosse Fuge, it serves to place the work in appropriate context as the culmination of Beethoven's development of the genre throughout the key stages of his incomparable career.

The earliest quartet recording of the Grosse Fuge appears to have been the version cut by the Léner Quartet for Columbia in 1927. The description of their playing by Robert Philip and Tully Potter in the 2001 Grove’s Dictionary is spot on: “Their playing was remarkable above all for rich and mellow tone-quality combined with an unusually homogeneous blend of the four instruments, finesse and beauty of phrasing and immaculate ensemble. The extraordinary smoothness and finish of their performances were universally acknowledged, but there were critics who found them over-sophisticated at times – particularly in works demanding rugged strength.” Indeed, their emphasis on grace and delicacy works well in Beethoven's earlier quartets but the overall aura of respectful caution leaves a great deal unsaid in the Grosse Fuge. Even so, the sheer audacity of their pioneering effort, enhanced by fine balance and precision, transcends mere historical curiosity and, aside from some mild portamento heralds a rather modern approach well ahead of its time. (A relic of the technology remains in their slowing down to prepare for the end of each side, a practice that made eminent sense when records had to be changed every four minutes but which adds an inappropriate sense of discontinuity nowadays.)

The next Grosse Fuge came the following year from the Budapest Quartet and was hailed by Gramophone for its biting tone, vigorous energy, breadth, courage and audacity (in contrast to the Léner's refinement), reflecting the values Beethoven brought to the music.  (Curiously, HMV "solved" the problem of which finale to use by issuing the Op. 130 Quartet without either one, ending with the cavatina, and "completing" the work with the Grosse Fuge as a separate 4-sided set one year later.) Despite the name, the Budapest members were all Russians educated in Germany, who became famed for their Beethoven quartet performances (including 60 complete cycles). As the resident quartet at the Library of Congress for 22 years, they played the Library's fabulous set of Stradivarius instruments, with which they recorded two complete cycles on mono and stereo LPs (and a partial one on 78s) for Columbia (now all on Sony CDs), to which can be added a live 1960 Library of Congress performance on Bridge CDs that rises to greater heights of visceral excitement. All are fundamentally similar and sound considerably more controlled than the Gramophone review would suggest. Yet they all contain a striking effect of letting the musicians' individuality occasionally disrupt the overall cohesion just enough to add an exciting edge to a fundamentally intellectualized reading, thus projecting a highly appropriate aura of hard, exploratory work that leaves significant things unsaid. (Curiously, HMV "solved" the problem of which finale to use by issuing the Op. 130 Quartet without either one, ending with the cavatina, and "completing" the work with the Grosse Fuge as a separate 4-sided set one year later.) Despite the name, the Budapest members were all Russians educated in Germany, who became famed for their Beethoven quartet performances (including 60 complete cycles). As the resident quartet at the Library of Congress for 22 years, they played the Library's fabulous set of Stradivarius instruments, with which they recorded two complete cycles on mono and stereo LPs (and a partial one on 78s) for Columbia (now all on Sony CDs), to which can be added a live 1960 Library of Congress performance on Bridge CDs that rises to greater heights of visceral excitement. All are fundamentally similar and sound considerably more controlled than the Gramophone review would suggest. Yet they all contain a striking effect of letting the musicians' individuality occasionally disrupt the overall cohesion just enough to add an exciting edge to a fundamentally intellectualized reading, thus projecting a highly appropriate aura of hard, exploratory work that leaves significant things unsaid.

Among the many modern recordings of the Grosse Fuge, only a relative few are available separately, often suitably paired with the B-flat Major Quartet, Op. 130 and its substituted finale.   (Many others are included in integral sets of all 16 Beethoven quartets, or boxes of the late five, but out of deference to readers' (and my) budgets, I'm only addressing those currently available on individual CDs.) Among the single discs, my favorites are the hair-raising precision and passion of the Cleveland Quartet (abetted by Telarc's finely detailed recording, 1996), the brash, quick vitality of the Orford Quartet (Delos, 1994, also benefiting from a crystalline recording), the swift and breathtaking passsion of the Yale Quartet (Vanguard, c. 1970 – I'm cheating a bit here since theirs is in a box set, but budget-priced), the confident ensemble and colorful textures of the Juilliard Quartet (captured live, but without the substitute finale, on Sony, 1996), and the extraordinary combination of vivid but polished execution and rich, imposing tone of the Guarneri Quartet (Philips, 1987 – not to be confused with their far more mellow and less engaged 1970 RCA recording). All of these transcend mere virtuosity (abundant though it is) and surface polish to not only reveal, but underline, the sheer sense of rough-hewn struggle inherent in this hugely challenging work. (I don't hear these essential qualities in other singletons by the Kodaly (Naxos, 1999), Alban Berg (EMI, 1980) and Borodin (Chandos) Quartets.) Even so, no single recording can fully capture the strange compelling power of this work that, by its very nature, is so intensely fruitful and profoundly complex as to defy revealing all of its riches through a sole performance. (Many others are included in integral sets of all 16 Beethoven quartets, or boxes of the late five, but out of deference to readers' (and my) budgets, I'm only addressing those currently available on individual CDs.) Among the single discs, my favorites are the hair-raising precision and passion of the Cleveland Quartet (abetted by Telarc's finely detailed recording, 1996), the brash, quick vitality of the Orford Quartet (Delos, 1994, also benefiting from a crystalline recording), the swift and breathtaking passsion of the Yale Quartet (Vanguard, c. 1970 – I'm cheating a bit here since theirs is in a box set, but budget-priced), the confident ensemble and colorful textures of the Juilliard Quartet (captured live, but without the substitute finale, on Sony, 1996), and the extraordinary combination of vivid but polished execution and rich, imposing tone of the Guarneri Quartet (Philips, 1987 – not to be confused with their far more mellow and less engaged 1970 RCA recording). All of these transcend mere virtuosity (abundant though it is) and surface polish to not only reveal, but underline, the sheer sense of rough-hewn struggle inherent in this hugely challenging work. (I don't hear these essential qualities in other singletons by the Kodaly (Naxos, 1999), Alban Berg (EMI, 1980) and Borodin (Chandos) Quartets.) Even so, no single recording can fully capture the strange compelling power of this work that, by its very nature, is so intensely fruitful and profoundly complex as to defy revealing all of its riches through a sole performance.

In this phenomenally bold and brilliant gesture, Beethoven not only reached far beyond the capacities of critics, performers and audiences of his time, but so much further – he pushed the outer limits of human musical understanding. Every composer (mostly toiling in obscurity) who dares to craft work of awesome personal significance, but without any concern with pleasing others, has followed in Beethoven's hallowed footsteps.

The most intriguing source of information about all things Beethoven is the massive biography begun by Alexander Wheelock Thayer. At the time of his death in 1897, he had devoted a half-century to his research but the volumes he was able to issue covered Beethoven's life only up to 1817. His work was continued by Hermann Dieters and then, following Deiters's death in 1907, completed by Hugo Reimann. The result was further edited by Henry Edward Krehbiel and published as The Life of Beethoven (G. Schirmer, 1921) and again by Elliott Forbes as Thayer's Life of Beethoven (Princeton University, 1969). Either version is warm, thorough and full of insight into the humanity of the great creator. Modern biographies I found to be especially helpful were Maynard Solomon's Beethoven (Schirmer, 1971) and George R. Marek's Beethoven – Biography of a Genius (Funk & Wagnalls, 1969). The most intriguing source of information about all things Beethoven is the massive biography begun by Alexander Wheelock Thayer. At the time of his death in 1897, he had devoted a half-century to his research but the volumes he was able to issue covered Beethoven's life only up to 1817. His work was continued by Hermann Dieters and then, following Deiters's death in 1907, completed by Hugo Reimann. The result was further edited by Henry Edward Krehbiel and published as The Life of Beethoven (G. Schirmer, 1921) and again by Elliott Forbes as Thayer's Life of Beethoven (Princeton University, 1969). Either version is warm, thorough and full of insight into the humanity of the great creator. Modern biographies I found to be especially helpful were Maynard Solomon's Beethoven (Schirmer, 1971) and George R. Marek's Beethoven – Biography of a Genius (Funk & Wagnalls, 1969).

Among specialized books that focus on the quartets are Joseph Kerman: The Beethoven Quartets (Knopf, 1966, reprinted by Norton, 1979); David Gregory Mason: The Quartets of Beethoven (Oxford, 1947); Harold Truscott: Beethoven's Late String Quartets (Dennis Dobson, 1968); Philip Radcliffe: Beethoven's String Quartets (Hutchinson University, 1965); Robert Winter and Robert Martin: The Beethoven Quartet Companion (University of California Press, 1994), which includes chapters by Joseph Kerman ("Beethoven Quartet Audiences"), Robert Winter ("Performing the Quartets in Their First Century") and Robert Martin ("The Quartets in Performance – a Player's Perspective"); and the chapter on Beethoven by Roger Fiske in Alec Robinson, ed.: Chamber Music (Penguin, 1957).

Copyright 2011 by Peter Gutmann

|