|

Was he or wasn’t he? (Religious, that is.)  One of the most intriguing questions raised by Ludwig van Beethoven’s Missa Solemnis is the extent to which it reflects the composer’s own religious feelings. On the one hand, he insisted that his nephew receive religious instruction and took the last sacrament himself (although, on the verge of death, he may have been too weak to protest). Yet biographers generally consider him a non-observant Catholic who was fascinated by other religions – they note that he had Persian aphorisms framed on his wall, leaned toward pantheism and felt no need for explanation by intermediaries of the unfathomable mysteries of life. Indeed, Beethoven shunned ritual and was in touch with Johann Michael Sailer, a theologian who rejected mechanical observance in favor of an individual believer’s interior experience of spirituality, a philosophy which resonated with Beethoven’s personal Enlightenment-derived conviction in freedom and reason. One of the most intriguing questions raised by Ludwig van Beethoven’s Missa Solemnis is the extent to which it reflects the composer’s own religious feelings. On the one hand, he insisted that his nephew receive religious instruction and took the last sacrament himself (although, on the verge of death, he may have been too weak to protest). Yet biographers generally consider him a non-observant Catholic who was fascinated by other religions – they note that he had Persian aphorisms framed on his wall, leaned toward pantheism and felt no need for explanation by intermediaries of the unfathomable mysteries of life. Indeed, Beethoven shunned ritual and was in touch with Johann Michael Sailer, a theologian who rejected mechanical observance in favor of an individual believer’s interior experience of spirituality, a philosophy which resonated with Beethoven’s personal Enlightenment-derived conviction in freedom and reason.

So why did Beethoven write a Mass? The ostensible reason was to honor Rudolph, the Archduke of Austria, who was to be invested as Archbishop in March 1820. Rudolph not only was Beethoven’s foremost patron, but a fine pianist and a personal friend, to whom Beethoven already had dedicated many of his greatest and most visionary works, including the “Hammerklavier” Piano Sonata, the “Archduke” Trio and the last two Piano Concertos; indeed, Beethoven’s tender 1810 Piano Sonata # 26 (“Farewell”) is thought to express his personal feelings when Rudolph was forced to move away from Vienna. So why did Beethoven write a Mass? The ostensible reason was to honor Rudolph, the Archduke of Austria, who was to be invested as Archbishop in March 1820. Rudolph not only was Beethoven’s foremost patron, but a fine pianist and a personal friend, to whom Beethoven already had dedicated many of his greatest and most visionary works, including the “Hammerklavier” Piano Sonata, the “Archduke” Trio and the last two Piano Concertos; indeed, Beethoven’s tender 1810 Piano Sonata # 26 (“Farewell”) is thought to express his personal feelings when Rudolph was forced to move away from Vienna.  Upon learning of Rudolph’s elevation in June 1819, Beethoven had written: “The day on which a High Mass composed by me will be performed during the ceremonies solemnized for your Imperial Highness will be the most glorious day of my life; and God will enlighten me so that my poor talents may contribute to the glorification of that solemn day.” Unlike most obsequious toadying to nobility of the time, Beethoven actually might have meant this. (But Maynard Solomon suggests that Beethoven may also have had an ulterior motive – he hoped to be appointed as the new archbishop’s kappelmeister.) Upon learning of Rudolph’s elevation in June 1819, Beethoven had written: “The day on which a High Mass composed by me will be performed during the ceremonies solemnized for your Imperial Highness will be the most glorious day of my life; and God will enlighten me so that my poor talents may contribute to the glorification of that solemn day.” Unlike most obsequious toadying to nobility of the time, Beethoven actually might have meant this. (But Maynard Solomon suggests that Beethoven may also have had an ulterior motive – he hoped to be appointed as the new archbishop’s kappelmeister.)

But there were plenty of other ways Beethoven could have honored Rudolph, and so his motivation may have run deeper. Thus, Willy Hess characterized the Missa Solemnis as “an avalanche released by a speck of dust.” Indeed, Hess noted that its use for its original liturgical purpose would have required long interruptions between each section in order to insert long passages of dry ceremony that would have ruined its organic unity and impaired its overall artistic impact. Rather, William Mann suggests that Beethoven seized upon the text not as dogma but as a means of questioning, confirming and enlarging the literal meaning in order to represent the struggle between the immensity of God and the inadequacy of mankind. Andrew Huth asserts that Beethoven wholeheartedly accepted the orthodox Catholic view of the Mass as a celebration of man and God coming together through prayer and faith. Thus, Mann observes, it served as an ideal vehicle to resolve Beethoven’s own crisis of faith and to assert his own religious philosophy, yet in a form that was familiar to most of the Western world and thus would be accessible to listeners. In that light, Solomon notes that Beethoven later offered his publisher a German language version to facilitate performance in Protestant communities.

|

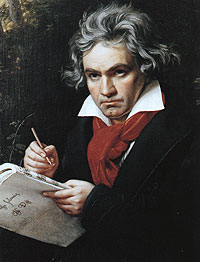

Beethoven writing the Missa Solemnis

(1819 oil painting by Joseph Carl Stieler) |

Beethoven invested much of himself in the Missa Solemnis. As preparation, he immersed himself in an intensive study of religious music of the past, from monastic chants to Handel’s Messiah (he incorporated the melody of “And He Shall Reign” into his Dona nobis pacem) and the Mozart Requiem, portions of which he copied out. Indeed, as Solomon notes, the result was an amalgam of styles, rooted in older traditions but empowered with the grandeur of the symphony. Anton Schindler, Beethoven’s biographer and assistant, recalled that one day in August 1819 he arrived at Beethoven’s lodgings around 4 PM: “From behind the closed door of one of the parlors we could hear the master working on the fugue of the Credo, singing, yelling, stomping his feet. … The door opened and Beethoven stood before us, his features distorted to the point of inspiring terror.” As William Drabkin notes, with the sole exception of his opera Fidelio, not only was this the largest and longest work Beethoven ever wrote, but it took him far longer to produce than any other. Indeed, Beethoven missed his deadline – by three years, as it was not finished until March 1823, when he presented it to Rudolph on the third anniversary of the installation ceremony.

George Marek observed that Beethoven, who was in constant need of funds, could have earned more by writing many smaller works but instead kept polishing this one. Alexander Wheelock Thayer quipped that the Missa Solemnis was “several times completed but never complete so long as it was within reach.” He elaborated: “The Mass is almost ready for delivery when he is in financial extremities; but when he has helped himself with loans or the collection of advances or the sale of old manuscripts or potboilers, his insatiable desire to revise, emend and improve his great work takes possession of him, and the vast amount of reworking and recopying thus pushes its ultimate completion into the future and precipitates yet another period of distress.” Clearly, the Missa Solemnis meant a lot to Beethoven. Indeed, he wrote over the opening: “Von Herzen – möge es wieder – zu Herzen gehn!” (“From the heart – may it return to the heart!”) – although only on the copy presented to Rudolph, and so it may have been a personal message for his friend rather than a dedication intended for humanity at large.

The Missa Solemnis was not Beethoven’s first religious work, although it certainly was the one in which he expressed himself most fully. In 1803 he had written an oratorio, Christus am Ölburg (Christ on the Mount of Olives), published as his Op. 85 after an 1811 revision. The Missa Solemnis was not Beethoven’s first religious work, although it certainly was the one in which he expressed himself most fully. In 1803 he had written an oratorio, Christus am Ölburg (Christ on the Mount of Olives), published as his Op. 85 after an 1811 revision.  Its subject must have had particular personal appeal as a catharsis following the crisis of Beethoven's incurable deafness and resultant depression. Indeed, Martin Cooper notes that it was Beethoven's first completed work after his wrenching and soul-baring Heilingenstadt Testament and that, by focusing on Christ’s agony in the Garden of Gethsemane, Beethoven identified with Christ’s suffering, terror and isolation while still desiring goodness and a love of mankind. Beethoven later claimed to have written Christus in a fortnight amid distractions, and the general consensus is that it is competent but formulaic and barely inspired. Thus Lewis Lockwood cites its “inconsistent quality … which ranges from routine recitatives and reasonably effective arias … to bombastic choral writing.” In any event, Christus clearly shows that Beethoven was not afraid to inject emotion into his religious writing, even if this work was as much a personal statement as a sacred one. Its subject must have had particular personal appeal as a catharsis following the crisis of Beethoven's incurable deafness and resultant depression. Indeed, Martin Cooper notes that it was Beethoven's first completed work after his wrenching and soul-baring Heilingenstadt Testament and that, by focusing on Christ’s agony in the Garden of Gethsemane, Beethoven identified with Christ’s suffering, terror and isolation while still desiring goodness and a love of mankind. Beethoven later claimed to have written Christus in a fortnight amid distractions, and the general consensus is that it is competent but formulaic and barely inspired. Thus Lewis Lockwood cites its “inconsistent quality … which ranges from routine recitatives and reasonably effective arias … to bombastic choral writing.” In any event, Christus clearly shows that Beethoven was not afraid to inject emotion into his religious writing, even if this work was as much a personal statement as a sacred one.

The other predecessor was Beethoven's 1807 Mass in C, Op. 86, which Prince Esterházy commissioned as the next annual Mass in memory of his wife following the six which Haydn had composed for him.  While Beethoven sought to depart from the model of his illustrious predecessor, to modern ears his work sounds much like respectful emulation of the established Viennese style, even though it is more somber and with less of Haydn's penchant toward four-square formality, propulsive momentum and an overall upbeat aura. Unfortunately, the only critic who really counted at the time was the Prince himself, who called it “unbearably ridiculous and detestable” and claimed to be “angry and mortified.” Needless to say, he turned elsewhere for future commissions, and Beethoven turned his attention to secular work. While Beethoven sought to depart from the model of his illustrious predecessor, to modern ears his work sounds much like respectful emulation of the established Viennese style, even though it is more somber and with less of Haydn's penchant toward four-square formality, propulsive momentum and an overall upbeat aura. Unfortunately, the only critic who really counted at the time was the Prince himself, who called it “unbearably ridiculous and detestable” and claimed to be “angry and mortified.” Needless to say, he turned elsewhere for future commissions, and Beethoven turned his attention to secular work.

For those of us who revere Beethoven as the supreme genius of Western music, one of the most troubling aspects of the Missa Solemnis is its marketing. As William Drabkin rather gingerly puts it: “The steps he took to sell the work … do not reveal the composer in the best light as a human being.” Marek is more blunt: to him, the negotiations for publication “represent one of the least credible moves of Beethoven’s life. Indeed, not to mince words, he behaved shockingly.” To summarize a long and sordid story, which Marek recounts in grueling detail, Beethoven sold the exclusive rights to each of seven publishers, only to invent excuses, retract accepted offers, promise other non-existent works, and play them off against each other with fictitious competing bids, all the while professing “to know nothing of business affairs” (as he wrote to one publisher) and accusing another of “playing a Jewish trick.” At the same time, he privately sold ten prepublication copies to royal patrons, including the kings of France, Prussia, Saxony and Denmark and the Czar of Russia. (The last turned out to be propitious, as it led to the only complete performance during Beethoven’s life.) To the extent that this behavior can be defended, it may stem from the fact that Beethoven considered this work to be his very best and thus felt a need for tangible validation of its value.

Unfortunately, the rest of the world came to share Beethoven’s view only belatedly.

|

Beethoven's autograph of mm 396-391 of the Agnus Dei

– no wonder the copyists had trouble reading his "appalling" notation |

Although it now appears that the Missa Solemnis received its premiere on March 24, 1824 in St. Petersburg as a charity concert for the benefit of widows of former orchestra members (although the massive Credo movement may have been omitted), the first full European performance did not occur until three years after Beethoven’s death (and then in Bohemia). Beethoven’s own Vienna raised severe barriers – Church authorities forbade the presentation of a solemn Mass in a public theatre, and the work was far too long and overpowering to be integrated into a genuine religious service. The partial premiere, and the only performance Beethoven ever attended, was of three movements (the Kyrie, Credo and Agnus Dei) which, to counter Church objections, were sung in German translation and billed as “Three Grand Hymns.” This was the same May 7, 1824 concert (Beethoven's last) at which the world first heard his Ninth Symphony.

Thankfully, Beethoven’s profound deafness spared him from actually hearing the performance, which must have been awful – he had not written out some of the instrumental parts, the copyists had great trouble reading his “appalling” notation, he was unable to make the kinds of adjustments that invariably emerge when preparing a first performance, rehearsal time was woefully insufficient for over two hours of new and thorny music, and the singers protested the difficulty of their parts. (Reportedly, since Beethoven wouldn’t know the difference, they just skipped the hard passages.) Schindler reported the concert to have been a great success, as did an empathetic report in the Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung: “The impact was indescribably marvelous and strong. [The Missa Solemnis] was acclaimed with enthusiastic shouts raised to the master from overflowing hearts, for his inexhaustible genius had opened up a new world to us, and unveiled never-heard, never-suspected magical secrets of divine music.” But others may have been less enthused – Joseph Carl Rosenbaum (a friend of Haydn, now best known for having stolen and kept that composer’s skull) wrote in his diary: “… lovely but tedious – not very full. Many boxes empty, no one from the Court. For all the large forces, little effect. B’s disciples clamoured, most of the audience stayed quiet, many did not wait for the end.” At a repeat performance on May 23, only the Kyrie was given. By the time the score was engraved Beethoven was too ill to correct the proofs, and the Missa Solemnis was issued only after his death. From the outset, the score generated debate over possible errors, the most crucial involving whether Beethoven really meant his soloists to be overwhelmed by the full orchestra in the Pleni and Osanna sections of the Sanctus, or whether he had intended the full chorus to sing but to save space had written out the choral parts on the same staves he had previously assigned to the soloists. (Nearly all conductors use the chorus.)

Although the Missa Solemnis has now taken its secure place among Beethoven’s supreme masterworks, Although the Missa Solemnis has now taken its secure place among Beethoven’s supreme masterworks,

|

| Soprano part from the Credo, mm 15-24 — OUCH!! |

it exerted little influence on other composers for a simple reason – it was performed so infrequently that few were able to hear it. The expense of assembling and rehearsing a large orchestra, soloists and chorus is often blamed, even though that never hindered the popularity of his equally massive and challenging Ninth Symphony. Rather, the major problem is the extreme difficulty of the score. The July 1882 Musical Times pronounced: “The work is impossible. No human lungs can endure the strain imposed by it.” The choral sopranos, especially, are called upon to sustain loud notes at the very top of their range for lengths that would surpass the stamina of many soloists. Thus beginning at bar 513 of the Gloria they are to hold a forte high A for about five seconds and at measure 21 of the Credo they are to sustain a fortissimo high B-flat for seven. Instrumental issues abound as well. Roger Fiske notes that Beethoven never wrote out separate parts for the bassoons and contrabassoon but just indicated “col bassi” (“[play] with the bass”) – yet these wind instruments cannot play the same long, continuous lines as a bowed string instrument for a half-minute or more without taking a breath.

|

| Tympani opening of the Gloria |

Thus, for example, the poor contrabassoons are to open the Gloria with 42 fortissimo bars of rapid eighth note figures, and then starting at bar 440 hold a single forte note for 18 measures (about 35 seconds). Not even the tympani are spared – also at the beginning of the Gloria they are assigned sixteenth note figures in clusters of two alternating between each drum that cannot possibly be played at the specified allegro vivace tempo. Arnold Werner-Jensen attributes all this to Beethoven’s refusal to compromise an artistic vision that surpassed the limitations of instruments and musicians of the era (and even today), to which I would add that it is these very same challenges of the work that add a human dimension of transcending our mortal reality in order to strive for idealism, even while requiring us to strain toward a distant, and perhaps unattainable, goal.

Nowadays, the Missa Solemnis is most often compared with Bach’s 1747-9 Mass in b minor, BWV 232 – which Beethoven was unlikely to have encountered, as it was only published in 1833.  Yet their structures are quite different – Bach’s Mass is comprised of self-contained homogenous movements, some of which dwell on the meaning of a single phrase of text, while Beethoven’s consists of five large blocks that combine the major sections of the Mass and flow amid shifting subjective moods. More significantly, each embodies the pinnacle of the divergent religious ideals of their respective composers and eras. Thus, the Bach, coming at the very end of his life, encapsulates his humility and a calm acceptance of his world and its boundaries, while the Missa Solemnis is bold, passionate and challenging, fully warranting the accusation hurled against Beethoven by his conservative detractors of being a “free-thinker.” If Bach’s is an affirmation of faith, Beethoven’s is the first major religious work to openly question it, and thus paves the way toward our modern artistic attitudes. In addition, Beethoven’s covers a far wider range of expression in order to plumb the depths of human experience, and shares with his other late works a “stream of consciousness” structure that manages to convincingly meld disparate elements into an integrated and challenging whole. As William Mann noted, Beethoven “wanted his audience to notice the knots in the wood and the hammer blows in the beaten metal.” Mann further notes that this intentional roughness is not just a personal fluke but is historically valid, as it stems from Beethoven’s study of older precedent harking back to the time of Palestrina before harmony and rhythms became so standardized. In any event, the Missa Solemnis was the end of the line, the last full-scale Mass by a major composer. (While Berlioz, Brahms, Verdi, Britten and others would produce equally imposing Masses, they were all requiems, and thus entail a far different religious attitude.) Yet their structures are quite different – Bach’s Mass is comprised of self-contained homogenous movements, some of which dwell on the meaning of a single phrase of text, while Beethoven’s consists of five large blocks that combine the major sections of the Mass and flow amid shifting subjective moods. More significantly, each embodies the pinnacle of the divergent religious ideals of their respective composers and eras. Thus, the Bach, coming at the very end of his life, encapsulates his humility and a calm acceptance of his world and its boundaries, while the Missa Solemnis is bold, passionate and challenging, fully warranting the accusation hurled against Beethoven by his conservative detractors of being a “free-thinker.” If Bach’s is an affirmation of faith, Beethoven’s is the first major religious work to openly question it, and thus paves the way toward our modern artistic attitudes. In addition, Beethoven’s covers a far wider range of expression in order to plumb the depths of human experience, and shares with his other late works a “stream of consciousness” structure that manages to convincingly meld disparate elements into an integrated and challenging whole. As William Mann noted, Beethoven “wanted his audience to notice the knots in the wood and the hammer blows in the beaten metal.” Mann further notes that this intentional roughness is not just a personal fluke but is historically valid, as it stems from Beethoven’s study of older precedent harking back to the time of Palestrina before harmony and rhythms became so standardized. In any event, the Missa Solemnis was the end of the line, the last full-scale Mass by a major composer. (While Berlioz, Brahms, Verdi, Britten and others would produce equally imposing Masses, they were all requiems, and thus entail a far different religious attitude.)

The overall structure of the Missa Solemnis, of course, adheres to the prescribed text. Musically, it’s a smooth fusion of styles ranging from monastic chant and polyphony through classical instrumentation to Beethoven’s own symphonic work, infused with many episodes of fugue (with which he was increasingly enamored) and even a touch of the theatre. Above all looms his astounding musical personality, which unifies the disparate elements with logic and inevitability into an organic expression of the most intimate yet universal experiences and aspirations of mankind. The overall structure of the Missa Solemnis, of course, adheres to the prescribed text. Musically, it’s a smooth fusion of styles ranging from monastic chant and polyphony through classical instrumentation to Beethoven’s own symphonic work, infused with many episodes of fugue (with which he was increasingly enamored) and even a touch of the theatre. Above all looms his astounding musical personality, which unifies the disparate elements with logic and inevitability into an organic expression of the most intimate yet universal experiences and aspirations of mankind.

Kyrie – The predominantly meditative Kyrie is the most traditional (and shortest) of the five movements. As with all prior settings, the text is so concise and simple (“Kyrie eleison, Christe eleison, Kyrie eleison”) that it demands elaboration. Bach devoted a separate lengthy movement to each phrase – intricate vocal fugues for the Kyries and a lovely soprano duet for the Christe. Beethoven, too, develops the text in a tripartite structure into which commentators have read much symbolism. Tovey finds an overwhelming sense of Divine glory contrasted with the nothingness of man in the opening 4/4 section in which the soloists are first heard trailing powerful choral chords. Mann views the fugal soloist-driven central portion as representing the dual human and divine nature of Christ. Fiske considers the final part, a variation on the first, as representing the Holy Spirit, derived, yet different, from the Father.

Gloria – With an ecstatic outburst of full chorus and orchestra

|

| The soaring theme of the Gloria |

Beethoven leaps away from respectful precedent into bold new territory, as every voice, both instrumental and vocal, proclaims at full throttle: “Gloria in excelsis Dio” (“Glory to God in the highest”). Generally, the movement follows the implications of each section of the text, both as to general mood (complex fugues and textures for portions of praise; tender solos for supplication), melody (an upward rush for “gloria;” a near monotone for “miserere nobis”), dynamics (pp for “adoramus te;” fff for omnipotens”) and accompaniment (nervous twittering for “miserere nobis;” a few bare pizzicato chords for the holy mystery of “quoniam tu solis”). The conclusion is electrifying – two massive fugues on the last line of text (“in gloria Dei Patris. Amen”), the last capped by a ecstatic minute-long presto that cranks up the elation to its utmost peak and culminates in an a capella shout of “Gloria!”

Credo – The Credo opens a fascinating window to the question we posed at the outset.

|

The theme of the Credo

– an authoritarian command |

Containing the bulk of the Mass text as a catalog of core beliefs, it challenges a composer to determine how to present all of them. Although Bach was Lutheran, he was deeply religious and accepted all the tenets of Christian faith, and so he treated each element of the Credo text with equivalent reverence and spread them among separate movements – seven choruses, an aria and a duet. Beethoven, though, took a far more subjective and selective approach in setting the entire text within a single integral movement. He sets the pace with a rather stentorian opening motif, sung by the basses, that suggests more an authoritarian command (“You will believe this”) rather then contented submission. As many commentators have noted, Beethoven emphasized certain portions while giving short shrift to others, and it seems reasonable to relate their relative prominence to the strength of his personal convictions. Thus he buries the doctrine of belief in one Catholic Church, mumbled quickly by the tenors beneath repeated choral shouts of “Credo,” while lavishing extended attention upon the portions addressing salvation, suffering and the incarnation. His greatest emphasis comes at the very end, where he devotes three separate sections comprising nearly a quarter of the entire movement to the single concluding line of “Et vitam venturi saeculi” (“And the life of the world to come”), thus strongly suggesting that his vision was directed to a better future – both his and ours – than to the trials of his (and our) earthly existence.

Sanctus – Beethoven saves his most personal touches for the two final movements.  His Sanctus is suitably soft and mellow, holding violins, flutes and oboes in reserve for the outburst of a brief, joyous fugue on Pleni sont coeli and Osanna in excelsis. Although prescribed ritual ordains that the concluding Benedictus section is to await a silent pause for the elevation of the Host, Beethoven combines it into the same movement with an inspired touch – an orchestral Praeludium of deep, slowly-evolving sustained chords, as if to recall the primordial state of existence and profound obscurity before the Creation. Flutes and a solo violin then flutter down from the heights of their range, awaken and intertwine with the soloists, and ultimately rouse the chorus, all in a ravishing Benedictus that stands as one of the most moving slow movements (and solo violin parts) that Beethoven ever fashioned. His Sanctus is suitably soft and mellow, holding violins, flutes and oboes in reserve for the outburst of a brief, joyous fugue on Pleni sont coeli and Osanna in excelsis. Although prescribed ritual ordains that the concluding Benedictus section is to await a silent pause for the elevation of the Host, Beethoven combines it into the same movement with an inspired touch – an orchestral Praeludium of deep, slowly-evolving sustained chords, as if to recall the primordial state of existence and profound obscurity before the Creation. Flutes and a solo violin then flutter down from the heights of their range, awaken and intertwine with the soloists, and ultimately rouse the chorus, all in a ravishing Benedictus that stands as one of the most moving slow movements (and solo violin parts) that Beethoven ever fashioned.

Agnus Dei – With the final movement Beethoven broke free of all convention. Barry Cooper, for one, feels that its theatricality and secularism impair the unity of the work, which until this point expresses personal feelings in abstract terms. Beethoven begins rather conventinally with a mournful, pleading Agnus Dei (“Lamb of God”) that rises from solo bass to soprano, with repeated insistence on “miserere,” subsides into a whisper, and slides seamlessly into a gently rolling 6/8 choral Dona nobis pacem (“Grant us peace”). But the closing leaves far behind any notion of ceremonial routine. While perhaps inappropriate in its time, it leapt ahead to anticipate the 20th century iconoclasm of Britten, Bernstein and others who used the Mass as the basis for crafting challenging works to probe and challenge the social and political mores of their own times.

Soloists, chorus and orchestra head toward the predictable satisfying end to the vast spiritual journey of the preceding hour with an affirmative final statement (firmly in the tradition of prior musical settings), but then are interrupted.

|

| The perfunctory end of the Agnus Dei (piano reduction) |

Pounding drums and trumpet fanfares intrude as the soloists, and then the full chorus, in clipped, terrified tones, turn the prayer for peace into a desperate plea. (Beethoven marks the lines as recitative and ängstlich – agitated.) Just as their fears subside and the flowing music appears headed once more for the expected triumphant conclusion, the full orchestra interrupts with an angry instrumental fugue, capped by shrill brass and thunderous percussive chords. Calm returns once more, but only to fall utterly silent to reveal the tympani rumbling menacingly in the distance. At last comes a final cadence, but in this militaristic context it sounds merely perfunctory, a wholly unconvincing attempt to dispel the persistent and lingering qualms as to where mankind is really heading.

As many have pointed out, Beethoven’s inspiration for this bold gesture may have been the first of Haydn’s Esterházy Masses, the Missa in Tempore Belli (“Mass in Time of War” – Haydn’s title), produced in 1796 as Napoleon was moving toward Vienna. Written in the normally carefree key of C major and mostly reflecting his irrepressible buoyancy, Haydn added uncharacteristic (and potentially sacrilegious) trumpets and drums to a brief somber opening (quickly dispelled by a cheery Kyrie) and to the closing Agnus Dei, which injected a hint of anxiety and desperation into the prayer for peace (but it, too, is followed by a substantial upbeat Dona nobis pacem to leave a final impression of jubilation). Rather than highlighting them in isolation, Haydn largely integrated his militaristic elements into the traditional plan of the Mass and used them to spice up the texture and only briefly to disrupt the mood, and so the impact was far less challenging than in the Missa Solemnis.

In any event, Beethoven headed the Dona nobis pacem section with a special inscription: “Bitte um innern und äussern Frieden” (“Prayer for inner and outer peace”). Thus he ends his most complex and arguably greatest work with a shrewd caution that a mind preoccupied with war cannot truly be joyful or at ease. Beethoven had lived through the Napoleonic wars (which, among other privations, had ruined the premiere of Fidelio, his only longer work) and here he clearly signals that until we have social and political stability, the inner contentment to which we all aspire will remain a cruel illusion. Thus Beethoven leaves us with an unsettled quest for faith rather than a comforting spiritual meditation, a deeply troubling question rather than a comforting affirmation.

Some may find this immature, sacrilegious, ignorant, smug, or all of the above, Some may find this immature, sacrilegious, ignorant, smug, or all of the above, but my template for performances of the Missa Solemnis is this: Beethoven poured four years of the peak of his life into creating this astounding work, and any valid performance must radiate an equivalent measure of dedication, sincerity and passion. Undemanding, steady, moderate approaches may be fitting and even preferable in other religious works with a pious mien, but not here. As Denis Stevens observed: “the Missa’s strength derives from the feeling of massive strain and tension, and if this is removed the whole point of the work disappears.” In a reversal of the old adage about not judging a book by its cover, the graphics and liner notes that accompany Missa Solemnis recordings by many famous artists seem more imbued with Beethoven’s spirit than their careful, balanced and respectful performances. Among these are the ones led by Jochum (Philips), Davis (Philips), Wand (Nonesuch LP – with the wonderful gatefold cover art shown at right by Roger Hane), Solti (Decca), Giulini (EMI), Ormandy (Sony), Shaw (Telarc) and Karajan (DG). but my template for performances of the Missa Solemnis is this: Beethoven poured four years of the peak of his life into creating this astounding work, and any valid performance must radiate an equivalent measure of dedication, sincerity and passion. Undemanding, steady, moderate approaches may be fitting and even preferable in other religious works with a pious mien, but not here. As Denis Stevens observed: “the Missa’s strength derives from the feeling of massive strain and tension, and if this is removed the whole point of the work disappears.” In a reversal of the old adage about not judging a book by its cover, the graphics and liner notes that accompany Missa Solemnis recordings by many famous artists seem more imbued with Beethoven’s spirit than their careful, balanced and respectful performances. Among these are the ones led by Jochum (Philips), Davis (Philips), Wand (Nonesuch LP – with the wonderful gatefold cover art shown at right by Roger Hane), Solti (Decca), Giulini (EMI), Ormandy (Sony), Shaw (Telarc) and Karajan (DG).

The following recordings (among those I've heard) convey to me much of the essence of the Missa Solemnis. While precise categories are impossible for great art, I've grouped them into three broad types – those having deep respect for the weighty basic solemnity of the work (stemming from Kittle’s and Koussevitzky's seminal recordings), those stressing its visceral excitement and revolutionary ardor (beginning with Walter's astounding 1948 concert), and those lavishing scrupulous attention to detail (beginning with Toscanini and extending through historically-informed attempts to recreate the sounds of Beethoven's era). Each recording is listed in the following format: Conductor – Soprano Soloist, Alto Soloist, Tenor Soloist, Bass Soloist; Choir(s), Orchestra (Year recorded, original label and format, CD reissue (if appropriate)).

- Bruno Kittel – Lotte Leonard / Emmy Land, Elenor Schlosshauer-Reynolds, Anton Maria Topitz / Eugen Transky, Wilhelm Guttmann / Hermann Schey; Bruno-Kittel-Chor, Berlin Philharmonic (1928, Polydor 78s, Japanese DG CDs)

The first recording of the Missa Solemnis was cut in 1928 by the Berlin Philharmonic led by Bruno Kittel on eleven Polydor 78s,

|

| The first side of the Kittel 78 set |

interchanging a total of seven soloists througout the various movements. Kittel was primarily known as a choral director, and the excellence of his choir was acclaimed throughout Europe and preserved in two superb recordings of the Beethoven Ninth by Fried (also 1928) and Furtwangler (1943). Alas, left to his own devices, and as one of Hitler’s favorite (and apparently compliant) musicians, his fame was tarnished by reportedly leading Nazi-commissioned and -themed works and by a 1941 Mozart Requiem recording in which he excised all possible references (Zion, Jerusalem) to the Jewish roots of Christianity, which Mortimer H. Frank termed “a symbol – foul as it may be – of the noxious impact of Nazism in general and the potentially insidious image resulting from any political manipulation of the arts.” As would be expected, the choral singing is rich and forceful (except for a brief blurred Osanna fugetto), and despite dynamic compression Kittel builds and relaxes his climaxes convincingly. Balances mostly are surprisingly good, even though the soloists occasionally are too prominent and a fair amount of overload distortion obscures the instrumental forces in the loudest passages. (I’m assuming that this is a flaw of the original 78s, which I’ve never heard, since Japanese transfers of historical 78s usually are quite accurate.) Generally, Kittel's leadership is sober and meditative, yielding a very slow overall timing of 85 minutes, although he does differentiate the various sections, even while working them into a evenly-flowing, well-integrated whole. The work reaches its emotional peak with an extraordinarily measured 23 minute Credo, in which the shimmering second section, Et incarnatus est, seems magically suspended in time and effectively sets an aura for the remainder in which drama is subsumed by reverence, somewhat spoiled only by a bland violin solo in the Benedictus and a flaccid orchestral fugue in the Agnus Dei – although the final timpani strokes are chillingly pronounced. Kittle’s deliberate approach set the pace for many others to come.

A reader kindly alerted me to a contemporaneous recording of a June 18, 1927 Barcelona concert to commemorate the centennial of Beethoven's death, given by the Orfeo Catala choral society and issued on a set of 12 Victor 78s (M-29). I've never encountered any LP or CD transfers, but judging from the Credo (the only portion I've been able to hear), the recording is rich and well-balanced, conductor Lluis Millet provides assured leadership, and the singing, by the society he had founded in 1891 and that was known for its technical polish, is precise yet full-bodied, smooth and expressive.

- Serge Koussevitzky – Jeanette Vreeland, Anna Kaskas, John Priebe, Norman Cordon; Harvard Glee Club, Radcliffe Choral Society, Boston Symphony (1938, Victor 78s, Pearl CDs)

Perhaps out of deference to the excellence of the Kittel venture, the next recording of the Missa Solemnis only came a full decade later,

|

The last side of the Koussevitzky 78 set

(image courtesy of stephsrecordsales.com) |

yet the producers apparently had so little confidence in its commercial prospects that they delayed release for three years. Koussevitzky approached music as a holy rite, and, rather ironically, the slow, steady tempos of his Missa Solemnis, while presumably intended to reflect his respect for the composer as well as his own sense of propriety and dignity, invoke the very sense of ritual that Beethoven sought to avoid in his own life. Thus, the entire opening Kyrie movement is leveled off to a uniform volume and both of the presto sections in the Gloria and Agnus Dei fugue are taken at the very same tempos as the preceding sections, denying them their flair. Yet the slow overall timing of nearly 83 minutes (including a 22-minute Credo), combined with an absence of drama, convincingly invests the entire work with an overall aura of deep deliberation. The amateur chorus and little-known soloists are wonderful, with the soprano and alto (who unfortunately misses an entire solo line in the Agnus Dei) given far more expressive leeway than the tightly-controlled chorale and orchestra. The recording, unfortunately, is quite blurred, with overpowering midrange that obscures much of the texture – and the soft tympani thuds that should infuse the ending with such subtle meaning are entirely inaudible and instead sound like grand pauses. Somewhat ironically, even though the chorus generally overwhelms the orchestra, the poor sonics lend an instrumental quality simply because the words are largely unintelligible and thus render the voices abstract. The recording apparently was made during a continuous session (it seems too quiet for a concert), with frequent missed notes between the 78 rpm sides, which change at regular intervals rather than at musically-logical transitions or pauses. While far less conspicuous in its time, the lapses are rather disruptive for modern listening (although in retrospect it is remarkable how seamlessly most works spread over multiple sides fit together, given the irrelevance of strict continuity during the 78 era, when gaps of several seconds were required to change or flip discs every few minutes). Setting aside the irony that a Nazi sympathizer had led a more empathetic reading than a devout American idol, the fact remains that Koussevitzky’s reading is little more than an historical artifact, thoroughly eclipsed artistically and technically by the Kittel set.

- Otto Klemperer – (1) Ilona Steingruber, Else Schuerhoff, Ernst Majkut, Otto Wiener; Akademiechor, Vienna Symphony (1953, Vox LP); (2) Elisabeth Soderstrom, Marga Höffgen, Waldemar Kmentt, Martti Talvela; New Philharmonia Orchestra and Chorus (1966, Angel LP, EMI CD)

Although recordings of several 1940s concerts have since emerged and been issued, the next Missa Solemnis to appear would have to await LPs.  Despite his reputation for stodgy tempos, Klemperer produced one of the swiftest Missas on record. Issued on the budget Vox label, it became an even greater bargain when reissued in 1959 on a single Vox LP in their "L-o-n-g-e-r Long Play" series, with each side's 36 minutes in surprisingly decent fidelity. Firmly in the Koussevitzky tradition (but nearly 11 minutes shorter and with a notably more enthusiastic Credo), Klemperer applies his trademark style of steady resolve, projecting Beethoven's variegated moods with tempos that animate the work without overt acceleration or accenting that would disrupt its fundamentally serious nature. The mono recording is decent, with an effective blend of vocal and instrumental forces that sufficiently distinguishes the textures and accompaniments. Klemperer's highly-acclaimed stereo remake is over 6 minutes slower and scores with a superb recording that glistens with bright detail (and with organ bass that can shred your speakers) and an extraordinary feeling of repressed energy threatening to be unleashed. The Gloria in particular finds the performers' zeal persistently pressing forward and threatening to tear through the orderly fabric – and when they do, just for a moment near the very end, the impact is astounding. Overall, Klemperer's conception impresses with its sheer self-assurance which generates an atmosphere of mastery and inevitability, even if occasionally sacrificing some of the tension that others mine throughout the work. A corollary recording is the one by Heather Harper, Janet Baker, Robert Tear, Hans Sotin, the New Philharmonia Chorus and the London Philharmonic conducted by Carlo Maria Giulini (1975, EMI), which features ravishing singing (perhaps too ravishing for this work) luxuriating over nearly 88 minutes (the slowest I've heard), all of which elevates the work to a plane of pure spirituality. Despite his reputation for stodgy tempos, Klemperer produced one of the swiftest Missas on record. Issued on the budget Vox label, it became an even greater bargain when reissued in 1959 on a single Vox LP in their "L-o-n-g-e-r Long Play" series, with each side's 36 minutes in surprisingly decent fidelity. Firmly in the Koussevitzky tradition (but nearly 11 minutes shorter and with a notably more enthusiastic Credo), Klemperer applies his trademark style of steady resolve, projecting Beethoven's variegated moods with tempos that animate the work without overt acceleration or accenting that would disrupt its fundamentally serious nature. The mono recording is decent, with an effective blend of vocal and instrumental forces that sufficiently distinguishes the textures and accompaniments. Klemperer's highly-acclaimed stereo remake is over 6 minutes slower and scores with a superb recording that glistens with bright detail (and with organ bass that can shred your speakers) and an extraordinary feeling of repressed energy threatening to be unleashed. The Gloria in particular finds the performers' zeal persistently pressing forward and threatening to tear through the orderly fabric – and when they do, just for a moment near the very end, the impact is astounding. Overall, Klemperer's conception impresses with its sheer self-assurance which generates an atmosphere of mastery and inevitability, even if occasionally sacrificing some of the tension that others mine throughout the work. A corollary recording is the one by Heather Harper, Janet Baker, Robert Tear, Hans Sotin, the New Philharmonia Chorus and the London Philharmonic conducted by Carlo Maria Giulini (1975, EMI), which features ravishing singing (perhaps too ravishing for this work) luxuriating over nearly 88 minutes (the slowest I've heard), all of which elevates the work to a plane of pure spirituality.

- Bruno Walter – Eleanor Steber, Nan Merriman, Walter Hain, Lorenzo Alvary; Westminster Choir, New York Philharmonic (1948 concert, Music and Arts CD)

Concert recordings from the middle phase of Walter’s career never cease to amaze me.  Before escaping from Europe, he led good, solid Romantic readings, and the 1950s brought an increasingly mellow, polished approach that culminated in genial, warm and idealized stereo LPs. In between, though, he produced some of the most incendiary concerts ever preserved on record. This one crackles with visceral elemental excitement, constantly pushing tempos and dynamics to the extreme, drawing deeply committed singing and playing from his forces, and holding its sections together – but only barely – with thrilling tension. The Gloria, in particular, is simply staggering in its volatile fervor. The long gap of silence between the final note and the storm of applause attests to the depth of the spiritual impact this astounding performance had on its audience. The audio quality is a vast improvement upon the first AS Disc release, but still leaves much to the imagination. Yet how can that matter when presented with an artistic statement of this exalted level? I truly pity those sad folks turn their backs on the splendors of the past, purporting to bemoan the impossibility of enjoying anything in less than allegedly pure digital sound. Before escaping from Europe, he led good, solid Romantic readings, and the 1950s brought an increasingly mellow, polished approach that culminated in genial, warm and idealized stereo LPs. In between, though, he produced some of the most incendiary concerts ever preserved on record. This one crackles with visceral elemental excitement, constantly pushing tempos and dynamics to the extreme, drawing deeply committed singing and playing from his forces, and holding its sections together – but only barely – with thrilling tension. The Gloria, in particular, is simply staggering in its volatile fervor. The long gap of silence between the final note and the storm of applause attests to the depth of the spiritual impact this astounding performance had on its audience. The audio quality is a vast improvement upon the first AS Disc release, but still leaves much to the imagination. Yet how can that matter when presented with an artistic statement of this exalted level? I truly pity those sad folks turn their backs on the splendors of the past, purporting to bemoan the impossibility of enjoying anything in less than allegedly pure digital sound.

- Erich Kleiber – (1) Nilda Hoffmann, Mafalda Rinaldi, Lydia Kindermann, Kolomon von Pataky, Emanuel List; Teatro Colon Orchestra and Chorus (1946 concert, Archipel CD), (2) Birgit Nilsson, Lisa Tunnel, Gosta Backlein, Sigurd Bjorling; Stockholm Philharmonic Orchestra and Chorus (1948 concert, Music & Arts CD)

That said, I do have my limits – and they’re sorely tested by a 1946 concert recording ostensibly by Erich Kleiber and the Teatro Colon Orchestra and Chorus.  Beyond the scratches, distortion and imprecise side joins to be expected from off-air recordings of this vintage, the transfer has shrill short-wave fidelity, horrendous wow, loud thumps, buzzes and even a half dozen beeps – a shame, since the performance itself (or at least what can be gleaned of it) nearly matches Walter’s for its bold intensity. Yet, there may be a fascinating mystery here. A 1948 Stockholm Philharmonic concert by Kleiber, in vastly better sound (and featuring a young Birgit Nilsson as the soprano soloist), seems a world apart, and not just sonically – every movement is far slower (86 v. 75 minutes overall) and replaces primal snarl with a hovering spiritual unity. Is it possible that the same conductor led such diametrically disparate readings – one among the very fastest and impassioned on record and the other among the most deliberate and mellow – barely two years apart? Indeed, in his liner notes to the Music & Arts release, Mark Kluge questions the authenticity of the earlier reading. Misattribution of aircheck recordings of this era are hardly unknown, especially when they appear on labels that tend to be, shall we say, haphazard in their pursuit of legal rights. Frankly, the latter recording seems more in keeping with Kleiber’s reputation for more steadfast integrity than volatility – decidedly more modeled after Koussevitzky/Klemperer than Walter/Bernstein. And yet, the two performances share certain traits, such as their overall concentration, and the brisk openings of their Glorias – and, after all, Kleiber’s famous 1953 Concertgebouw recording of the Beethoven Fifth is widely hailed not for a patient, intellectual unfolding but rather for the rapid pace and relentless drive of its allegro con brio. Other details, though, are so different as to seem irreconcilable – thus, the timpani roll at m. 488 of the Gloria is massive in 1948 but nowhere to be heard in 1946. So, pending authentication of the intensely vibrant and impulsive Colon performance (and in the hope of appreciably better source material), the question of authenticity must remain. But if it turns out to have been led by someone other than Kleiber, I’d sure like to know who! Beyond the scratches, distortion and imprecise side joins to be expected from off-air recordings of this vintage, the transfer has shrill short-wave fidelity, horrendous wow, loud thumps, buzzes and even a half dozen beeps – a shame, since the performance itself (or at least what can be gleaned of it) nearly matches Walter’s for its bold intensity. Yet, there may be a fascinating mystery here. A 1948 Stockholm Philharmonic concert by Kleiber, in vastly better sound (and featuring a young Birgit Nilsson as the soprano soloist), seems a world apart, and not just sonically – every movement is far slower (86 v. 75 minutes overall) and replaces primal snarl with a hovering spiritual unity. Is it possible that the same conductor led such diametrically disparate readings – one among the very fastest and impassioned on record and the other among the most deliberate and mellow – barely two years apart? Indeed, in his liner notes to the Music & Arts release, Mark Kluge questions the authenticity of the earlier reading. Misattribution of aircheck recordings of this era are hardly unknown, especially when they appear on labels that tend to be, shall we say, haphazard in their pursuit of legal rights. Frankly, the latter recording seems more in keeping with Kleiber’s reputation for more steadfast integrity than volatility – decidedly more modeled after Koussevitzky/Klemperer than Walter/Bernstein. And yet, the two performances share certain traits, such as their overall concentration, and the brisk openings of their Glorias – and, after all, Kleiber’s famous 1953 Concertgebouw recording of the Beethoven Fifth is widely hailed not for a patient, intellectual unfolding but rather for the rapid pace and relentless drive of its allegro con brio. Other details, though, are so different as to seem irreconcilable – thus, the timpani roll at m. 488 of the Gloria is massive in 1948 but nowhere to be heard in 1946. So, pending authentication of the intensely vibrant and impulsive Colon performance (and in the hope of appreciably better source material), the question of authenticity must remain. But if it turns out to have been led by someone other than Kleiber, I’d sure like to know who!

- Leonard Bernstein – Eileen Farrell, Carol Smith, Richard Lewis, Kim Borg; Westminster Choir, New York Philharmonic (1960, Columbia LP, Sony CD)

Among relatively traditional performances, this first stereo Missa Solemnis is my favorite.  Bernstein follows in the tradition set by Walter with the same choir and orchestra by eschewing smooth surface polish for a tough, sinewy approach, abetted by a closely-miked recording that highlights all the details. While far more tightly controlled and integrated than Walter’s hyper-dramatic dissection, Bernstein still conveys the work’s abundant energy with great conviction but within a more traditional context, and manages to project an overall aura of straining just enough to realize Beethoven’s overwhelming conception without abandoning the bounds of professional musicianship. The touch of iconoclasm was extended by the original LP liner notes, which consisted of extensive excerpts from Beethoven’s deceitful correspondence with his would-be publishers. Bernstein’s 1979 remake with the Hilversum Choir and Concergebouw Orchestra (DG LP and CD) is quite good, yet loses the edginess and passion he generated in New York in favor of a smoother blend. At the risk of sounding too chauvinistic for a work that preaches universality, perhaps Bernstein’s two recordings illustrate a fundamental difference between American and European approaches to interpretation. While far more polished than the 1960 Bernstein reading, the deeply heartfelt live Salzburg Festival recording by Cheryl Studer, Jessye Norman, Placido Domingo, Kurt Moll and the Vienna Philharmonic led by Bernstein protégé James Levine (1991, DG) invokes a similar impact by trying to squeeze every last drop of feeling from the work, although on occasion (especially in the Kyrie) it veers toward self-conscious operatic excess (hardly unexpected from its stellar cast of soloists and Levine's deep experience in the opera pit). Also in the category of visceral thrills, but with a diametrically opposite approach from Levine, is the recording by David Zinman, noted below. Bernstein follows in the tradition set by Walter with the same choir and orchestra by eschewing smooth surface polish for a tough, sinewy approach, abetted by a closely-miked recording that highlights all the details. While far more tightly controlled and integrated than Walter’s hyper-dramatic dissection, Bernstein still conveys the work’s abundant energy with great conviction but within a more traditional context, and manages to project an overall aura of straining just enough to realize Beethoven’s overwhelming conception without abandoning the bounds of professional musicianship. The touch of iconoclasm was extended by the original LP liner notes, which consisted of extensive excerpts from Beethoven’s deceitful correspondence with his would-be publishers. Bernstein’s 1979 remake with the Hilversum Choir and Concergebouw Orchestra (DG LP and CD) is quite good, yet loses the edginess and passion he generated in New York in favor of a smoother blend. At the risk of sounding too chauvinistic for a work that preaches universality, perhaps Bernstein’s two recordings illustrate a fundamental difference between American and European approaches to interpretation. While far more polished than the 1960 Bernstein reading, the deeply heartfelt live Salzburg Festival recording by Cheryl Studer, Jessye Norman, Placido Domingo, Kurt Moll and the Vienna Philharmonic led by Bernstein protégé James Levine (1991, DG) invokes a similar impact by trying to squeeze every last drop of feeling from the work, although on occasion (especially in the Kyrie) it veers toward self-conscious operatic excess (hardly unexpected from its stellar cast of soloists and Levine's deep experience in the opera pit). Also in the category of visceral thrills, but with a diametrically opposite approach from Levine, is the recording by David Zinman, noted below.

- Arturo Toscanini – (1) Zinka Milanov, Kerstin Thorborg, Koloman von Pataky, Nicola Moscona; BBC Choral society, BBC Symphony (1939 concert, BBC Legends CD); (2) Zinka Milanov, Bruna Castagna, Jussi Björling, Alexander Kipnis; Westminster Choir, NBC Symphony (1940 concert, Music and Arts CD); (3) Lois Marshall, Nan Merriman, Eugene Conley, Jerome Hines; Robert Shaw Chorale, NBC Symphony (1953, RCA LP, BMG CD)

Amazingly, Toscanini never conducted the Missa Solemnis until he turned 66, but apparently it took that long to percolate.  His three generally available performances project the same piercing attention to detail, a distillation down to bare essence, steady pacing, razor-sharp attacks, and an overall avoidance of interpretive rhetoric, all of which create vast respect for the composer’s conception, which, of course, was Toscanini’s professed aim. (An earlier 1935 New York Philharmonic concert, available from private sources, while satisfying on its own terms, is far more pliant and "mainstream" and perhaps reflects a period of gestation before the emergence of Toscanini's ultimate view of the work.) One particular aspect common to all three – Toscanini shrugs off the end with a thoroughly bland advance to the final cadence, which he takes in strict tempo with no emphasis whatever, thus fully conveying a sense of its inadequacy to dispel the terror of looming war (an attitude which, I feel, Beethoven fully intended to express). (Several other conductors (Davis, Jochum) take an opposite, yet effective, approach by slowing down the final climax so that it emerges only gingerly, as if jubilation were hesitant to emerge in such hostile surroundings.) Toscanini's 1953 studio recording gains a measure of exhilaration from its faster tempos and has the best sonics. Yet artistically it is eclipsed by the two earlier concerts, which temper the simplified uniform pacing and textures of 1953 with greater flexibility and a certain degree of repose that magnify the impact of their climaxes. Of those, the 1939 London concert may have better overall balance, but the 1940 New York concert adds extra punch to its soaring moments with piercing brass and more prominent tympani. Although widely circulated for decades with dim sound on many labels, the rich yet well-defined 2003 Music and Arts restoration of the 1940 concert by Graham Newton approaches high fidelity. His three generally available performances project the same piercing attention to detail, a distillation down to bare essence, steady pacing, razor-sharp attacks, and an overall avoidance of interpretive rhetoric, all of which create vast respect for the composer’s conception, which, of course, was Toscanini’s professed aim. (An earlier 1935 New York Philharmonic concert, available from private sources, while satisfying on its own terms, is far more pliant and "mainstream" and perhaps reflects a period of gestation before the emergence of Toscanini's ultimate view of the work.) One particular aspect common to all three – Toscanini shrugs off the end with a thoroughly bland advance to the final cadence, which he takes in strict tempo with no emphasis whatever, thus fully conveying a sense of its inadequacy to dispel the terror of looming war (an attitude which, I feel, Beethoven fully intended to express). (Several other conductors (Davis, Jochum) take an opposite, yet effective, approach by slowing down the final climax so that it emerges only gingerly, as if jubilation were hesitant to emerge in such hostile surroundings.) Toscanini's 1953 studio recording gains a measure of exhilaration from its faster tempos and has the best sonics. Yet artistically it is eclipsed by the two earlier concerts, which temper the simplified uniform pacing and textures of 1953 with greater flexibility and a certain degree of repose that magnify the impact of their climaxes. Of those, the 1939 London concert may have better overall balance, but the 1940 New York concert adds extra punch to its soaring moments with piercing brass and more prominent tympani. Although widely circulated for decades with dim sound on many labels, the rich yet well-defined 2003 Music and Arts restoration of the 1940 concert by Graham Newton approaches high fidelity.

- John Eliot Gardiner – Charlotte Margiono, Catherine Robbin, William Kendall, Alastair Miles; Monteverdi Choir, English Baroque Soloists (1990, Archiv CD)

Perhaps the true heir of Toscanini's drive toward simplicity was the historical performance movement that emerged in full force in the 1980s. Among the few recordings of the Missa Solemnis that strive for period authenticity, Gardiner's has attracted consistent critical plaudits. Indeed, the attempt to realize the grandeur of Beethoven's conception with the modest resources of his time can be seen as another aspect of the struggle inherent in his work – the limited number of choral voices and an absence of the depth and force that we associate with (and have come to expect from) modern instruments at times seem unequal to the task. Yet, something crucial is gained by the effort to replicate the vastly different timbres of two centuries ago. It can be heard in the very first chord – reedy winds, crisp drums and a balance in which the strings blend into, rather than overwhelm, the ensemble. The soloists' minimal vibrato imparts their texts with a natural sincerity far removed from the suggestions of artifice and theatricality of the more common operatic projection, and thus creates a sense of direct communication, as does the plaintive solo violin in the Benedictus, which avoids the cloying sentimentality of some other renditions. Incidentally, Gardiner is one of the few to follow the original score by using the soloists, rather than the full chorus, in the Sanctus. was the historical performance movement that emerged in full force in the 1980s. Among the few recordings of the Missa Solemnis that strive for period authenticity, Gardiner's has attracted consistent critical plaudits. Indeed, the attempt to realize the grandeur of Beethoven's conception with the modest resources of his time can be seen as another aspect of the struggle inherent in his work – the limited number of choral voices and an absence of the depth and force that we associate with (and have come to expect from) modern instruments at times seem unequal to the task. Yet, something crucial is gained by the effort to replicate the vastly different timbres of two centuries ago. It can be heard in the very first chord – reedy winds, crisp drums and a balance in which the strings blend into, rather than overwhelm, the ensemble. The soloists' minimal vibrato imparts their texts with a natural sincerity far removed from the suggestions of artifice and theatricality of the more common operatic projection, and thus creates a sense of direct communication, as does the plaintive solo violin in the Benedictus, which avoids the cloying sentimentality of some other renditions. Incidentally, Gardiner is one of the few to follow the original score by using the soloists, rather than the full chorus, in the Sanctus.

- David Zinman – Luba Orgonasova, Anna Larsson, Reiner Trost, Franz-Josef Selig; Schweizer Kammerchor, Tonhalle Orchestra Zurich (2001, Arte Nova CD)

Here, we have a "hybrid" approach to the Missa Solemnis, which combines modern instruments with the balances and style of the early Romantic era.  The timing alone announces the special nature of this recording – less than 66 minutes! – although it's hardly a surprise from the same forces that brought us a 59-minute Beethoven Ninth. Yet, it never sounds rushed, but rather ardent, as the tempos, while fast, are fully integrated into a convincing fabric, with sufficent respites to prepare for the next jolt of energy, and many wondrous features along the way – the Christe Eleison takes off like a heady waltz, the winds add lovely grace notes to the Gratias section of the Gloria, and the Gloria and Credo fugues boast superb clarity, despite the delirious tempos, the density of the writing and the considerable number of voices (90) and instruments (70) used. The voices and an especially prominent organ dominate the texture to impart a "churchy" sound. My only disappointment is that, despite thunderous drums, the military outbursts have diminshed impact. Overall, though, Zinman and his Swiss players bypass the gloss of the past to impart a thrilling sense of consistent vitality and fresh discovery, making the work vastly accessible – which, after all, is what Beethoven had intended. Among modern recordings, this is an ideal introduction to the glories of this fabulous work. The other extreme for a hybrid approach is by Eva Mai, Marjana Lopovšek, Anthony Rolfe Johnson, Robert Hall, the Arnold Schoenberg Chor and the Chamber Orchestra of Europe led by Nikolaus Harnoncourt (1992, Teldec CD), who take a far more leisurely 81 minute excursion. Although they produce a somewhat thinner sound by complementing their modern instruments with narrow-bore trombones, natural trumpets and small, less-resonant tympani, they generally emphasize the reverential, rather than the revolutionary, aspect of a work which continues to fascinate and compel listeners for the very reason that Beethoven so brilliantly managed to balance both elements in such a compelling and personal way. The timing alone announces the special nature of this recording – less than 66 minutes! – although it's hardly a surprise from the same forces that brought us a 59-minute Beethoven Ninth. Yet, it never sounds rushed, but rather ardent, as the tempos, while fast, are fully integrated into a convincing fabric, with sufficent respites to prepare for the next jolt of energy, and many wondrous features along the way – the Christe Eleison takes off like a heady waltz, the winds add lovely grace notes to the Gratias section of the Gloria, and the Gloria and Credo fugues boast superb clarity, despite the delirious tempos, the density of the writing and the considerable number of voices (90) and instruments (70) used. The voices and an especially prominent organ dominate the texture to impart a "churchy" sound. My only disappointment is that, despite thunderous drums, the military outbursts have diminshed impact. Overall, though, Zinman and his Swiss players bypass the gloss of the past to impart a thrilling sense of consistent vitality and fresh discovery, making the work vastly accessible – which, after all, is what Beethoven had intended. Among modern recordings, this is an ideal introduction to the glories of this fabulous work. The other extreme for a hybrid approach is by Eva Mai, Marjana Lopovšek, Anthony Rolfe Johnson, Robert Hall, the Arnold Schoenberg Chor and the Chamber Orchestra of Europe led by Nikolaus Harnoncourt (1992, Teldec CD), who take a far more leisurely 81 minute excursion. Although they produce a somewhat thinner sound by complementing their modern instruments with narrow-bore trombones, natural trumpets and small, less-resonant tympani, they generally emphasize the reverential, rather than the revolutionary, aspect of a work which continues to fascinate and compel listeners for the very reason that Beethoven so brilliantly managed to balance both elements in such a compelling and personal way.

Information used in the historical portion of this article came primarily from the following sources: Information used in the historical portion of this article came primarily from the following sources:

- Two monographs devoted to extensive background and analyses:

- William Drabkin: Beethoven – Missa Solemnis (Cambridge University Press, 1991)

- Roger Fiske: Beethoven’s Missa Solemnis (Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1979)

- Biographies containing valuable information about the composer during this period:

- Maynard Solomon: Beethoven (Schirmer, 1998)

- Lewis Lockwood: Beethoven – The Musician and the Life (Norton 2003)

- George Marek: Beethoven – Biography of a Genius (Thomas Y. Crowell Company, 1969)

- Notes to LP sets:

- Ernest Newman – Toscanini/NBC studio performance, RCA LM-6013

- James B. Rich – Kloor/Palatinate Philharmonia, Musical Heritage Society 1048/9

- William Mann – Klemperer/Philharmonia, Angel SB-3679

- Hans Schmidt – Davis/London Philharmonic, Philips 9500 542/4

- Andrew Huth – Solti/Chicago, London 411-842

- Notes to CDs:

- Arnold Werner-Jensen – Bernstein/Concertgebouw, DG 413 780-2

- Denis Stevens – Bernstein/NY Philharmonic, Sony SM2K 47522

- Introductions to scores:

- Willy Hess – introduction to the English Eulenburg score

- Max Unger – introduction to the German Eulenburg score

Copyright 2011 by Peter Gutmann

|