|

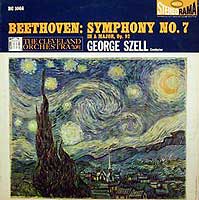

Of Beethoven’s “major” symphonies (that is, in the sense of innovation and prominence) the Seventh has aroused the widest spectrum of efforts to “interpret” its meaning. No such compulsion plagues the others – the “Choral” is guided by its text, the Fifth traces an emotional passage from grim determination to triumph, and Beethoven himself proclaimed his inspiration for the “Eroica” and labeled and described the movements of the “Pastoral.” But his Symphony # 7 in A major, Op. 92 is without such markers, and has drawn legions of commentators who felt compelled to explicate it. Arguably, that’s a sign of inspired subtlety – of the work, not the pundits – and a tribute to its remarkable ability to summon a broad spectrum of deeply personal and highly diverse response among listeners. the Seventh has aroused the widest spectrum of efforts to “interpret” its meaning. No such compulsion plagues the others – the “Choral” is guided by its text, the Fifth traces an emotional passage from grim determination to triumph, and Beethoven himself proclaimed his inspiration for the “Eroica” and labeled and described the movements of the “Pastoral.” But his Symphony # 7 in A major, Op. 92 is without such markers, and has drawn legions of commentators who felt compelled to explicate it. Arguably, that’s a sign of inspired subtlety – of the work, not the pundits – and a tribute to its remarkable ability to summon a broad spectrum of deeply personal and highly diverse response among listeners.

Just what does the Symphony # 7 mean? According to mid-19th century authorities, when the trend seemed to have peaked, it was a procession in an old cathedral or catacombs (Joseph d’Ortegue, 1863), a love-dream of a sumptuous odalesque (F.L.S. von Durenburg, 1863), a tale of Moorish knighthood (A. B. Marx, 1859), scenes from a masquerade (Alexander d’Oulibisheff, 1857) or a sequel to the Pastoral Symphony that “conjures up pictures of the autumnal merry-makings of the gleaners and wine-dressers, the tender melancholy of love-lorn youth, the pious canticle of joy and gratitude for nature’s gifts and the final outburst when joy beckons again and the dance melodies float out upon the air and none stands idle” (Ludwig Bischoff, 1859). Even fellow composers jumped in – Robert Schumann envisioned a peasant wedding, Hector Berlioz heard a “ronde des paysans” and, perhaps most famously, Richard Wagner characterized the whole as an “apotheosis of the dance.” But even their fertile speculation had been trumped by a Dr. Karl Iken, editor of the Bremer Zeitung and a contemporary of Beethoven, who wrote an extensive concert program that depicted a political revolution in great detail, beginning: Just what does the Symphony # 7 mean? According to mid-19th century authorities, when the trend seemed to have peaked, it was a procession in an old cathedral or catacombs (Joseph d’Ortegue, 1863), a love-dream of a sumptuous odalesque (F.L.S. von Durenburg, 1863), a tale of Moorish knighthood (A. B. Marx, 1859), scenes from a masquerade (Alexander d’Oulibisheff, 1857) or a sequel to the Pastoral Symphony that “conjures up pictures of the autumnal merry-makings of the gleaners and wine-dressers, the tender melancholy of love-lorn youth, the pious canticle of joy and gratitude for nature’s gifts and the final outburst when joy beckons again and the dance melodies float out upon the air and none stands idle” (Ludwig Bischoff, 1859). Even fellow composers jumped in – Robert Schumann envisioned a peasant wedding, Hector Berlioz heard a “ronde des paysans” and, perhaps most famously, Richard Wagner characterized the whole as an “apotheosis of the dance.” But even their fertile speculation had been trumped by a Dr. Karl Iken, editor of the Bremer Zeitung and a contemporary of Beethoven, who wrote an extensive concert program that depicted a political revolution in great detail, beginning:

The sign of revolt is given; there is a rushing and running about of the multitude; an innocent man, or party, is surrounded, overpowered after a struggle and haled before a legal tribunal. Innocency weeps; the judge pronounces a harsh sentence; sympathetic voices mingle in laments and denunciations. … The magistrates are now scarcely able to quiet the wild tumult. The uprising is suppressed, but the people are not quieted; hope smiles cheeringly and suddenly the voice of the people pronounces the decision in harmonious agreement.

Alexander Wheeler Thayer asserted that “such balderdash disgusted and even enraged Beethoven” and that in 1819 “he dictated a letter … in which he protested energetically against such interpretations of his music.”

Beethoven in 1814

by Louis-Rene Letronne

|

The tide turned in due course. Writing in 1935, Donald Francis Tovey dismissed the “sad nonsense” of “a long time ago,” and proclaimed the Seventh “so overwhelmingly convincing and so obviously untranslatable that it has for many generations been treated quite reasonably as a piece of music, instead of an excuse for discussing the French Revolution.” Nowadays, most analysts seem content to follow Tovey’s approach. Thus Paul Affelder dismisses the irreconcilable range of all the past imagery as proof of its futility. William Mann agrees that the Seventh can only be viewed as abstract art, calling it “an argument in terms of music. … It is about melodic shapes, tunes and vestiges of tunes, about harmony and the effect that a new chord can make and build up, about keys and the effect one key can have on another, about the relationship of wind to string to brass instruments.” In that light, Richard Freed regards the Seventh as “a triumphant discourse by a man intoxicated with the spirit of creativity itself.” In a similar vein, although the Seventh has been choreographed, Charles O’Connell cautions that any association with the dance should not be literal, but rather in the sense of artistic spirituality – dancing with words and the pen rather than with feet.

Yet, while we may disparage the overblown literary efforts of past critics to attribute symbolic imagery to the Seventh, they provide a spur for fruitful thought. Thus, in retrospect, Maynard Solomon points to the common thread of a carnival or festival image as resonating our human desire for a temporary release from subjugation to the prevailing social order and a suspension of customary norms, a joyous lifting of restraints and an outpouring of mockery, all of which permeate the score. And Tim McDonald attributes the past tendency to the composer’s anti-social turbulent nature, which left the field wide open and, on a positive note, reflects the overriding sense of enthusiasm and excitement that the work generates.

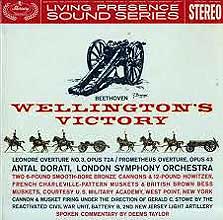

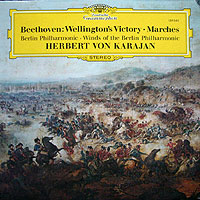

Yet, while explicit interpretation may be dubious, the Seventh – unlike nearly all Beethoven’s other orchestral works – may have been prompted by more than the composer’s whim. Its premiere performance took place in Vienna on December 8, 1813 and was hailed as a great success, although not because of the symphony itself. Rather, it anchored a novelty program featuring Beethoven’s Wellington’s Victory or the Battle of Vittoria, Op. 91, and two marches by Dussek and Pleyel for a mechanical trumpeter invented by Johann Nepomuk Maelzel, who enjoyed a close, if rocky, relationship to the composer, who frequented the Maelzel workshop. Maelzel had constructed an ear-trumpet that Beethoven found useful, and later would perfect the metronome upon which Beethoven would rely to specify tempos for his works. George Marek characterized Maelzel as “half Edison, half Barnum,” as evidenced by a bogus mechanical chess player that was found to have a man inside. Yet, while explicit interpretation may be dubious, the Seventh – unlike nearly all Beethoven’s other orchestral works – may have been prompted by more than the composer’s whim. Its premiere performance took place in Vienna on December 8, 1813 and was hailed as a great success, although not because of the symphony itself. Rather, it anchored a novelty program featuring Beethoven’s Wellington’s Victory or the Battle of Vittoria, Op. 91, and two marches by Dussek and Pleyel for a mechanical trumpeter invented by Johann Nepomuk Maelzel, who enjoyed a close, if rocky, relationship to the composer, who frequented the Maelzel workshop. Maelzel had constructed an ear-trumpet that Beethoven found useful, and later would perfect the metronome upon which Beethoven would rely to specify tempos for his works. George Marek characterized Maelzel as “half Edison, half Barnum,” as evidenced by a bogus mechanical chess player that was found to have a man inside.  Among his more spectacular genuine inventions was the “panharmonicon,” which, according to Sedgwick Clark, was “a giant mechanical orchestral machine, run by air pressure and incorporating flutes, trumpets, drums, cymbals, triangles, strings stuck by hammers, violins, cellos and clarinets.” According to Thayer, Maelzel wanted to popularize his device in London, and seized upon Wellington’s defeat of Napoleon at Vittoria to commission Beethoven to write a commemorative piece for it. In the meantime, to raise money for the venture, he produced a concert in Vienna that would serve as Beethoven’s first akademie (in which new works were presented) in five years, for which he suggested that Beethoven arrange Wellington’s Victory for orchestra and a battery of percussion. Ignaz Moscheles, who claimed to have witnessed the origin and progress of the work, asserted that Beethoven unfairly minimized the contributions of Maelzel, who laid out the whole design, fashioned the characteristic drum and trumpet flourishes and suggested the varied treatments of the French and British national anthems. According to Anton Schindler, even before the initial concert they had a falling out – Maelzel claimed that Beethoven had gifted him the work outright as collateral for a loan, and Beethoven retaliated by suing, claiming that Maelzel had mutilated the score which he had obtained by pretense. Among his more spectacular genuine inventions was the “panharmonicon,” which, according to Sedgwick Clark, was “a giant mechanical orchestral machine, run by air pressure and incorporating flutes, trumpets, drums, cymbals, triangles, strings stuck by hammers, violins, cellos and clarinets.” According to Thayer, Maelzel wanted to popularize his device in London, and seized upon Wellington’s defeat of Napoleon at Vittoria to commission Beethoven to write a commemorative piece for it. In the meantime, to raise money for the venture, he produced a concert in Vienna that would serve as Beethoven’s first akademie (in which new works were presented) in five years, for which he suggested that Beethoven arrange Wellington’s Victory for orchestra and a battery of percussion. Ignaz Moscheles, who claimed to have witnessed the origin and progress of the work, asserted that Beethoven unfairly minimized the contributions of Maelzel, who laid out the whole design, fashioned the characteristic drum and trumpet flourishes and suggested the varied treatments of the French and British national anthems. According to Anton Schindler, even before the initial concert they had a falling out – Maelzel claimed that Beethoven had gifted him the work outright as collateral for a loan, and Beethoven retaliated by suing, claiming that Maelzel had mutilated the score which he had obtained by pretense.

Billed as a benefit for wounded Austrian and Bavarian soldiers and fueled in significant part by the celebratory mood now that Napoleon’s seemingly unstoppable conquest of Europe (and its threat of French hegemony) at last had run aground, the premiere was a gala affair, with many of Vienna’s celebrity musicians, including Hummel, Spohr, Salieri, Meyerbeer and Moscheles, recruited to play the percussion. Thayer, though, claimed that they viewed it as a gigantic professional frolic and a stupendous musical joke. Beethoven conducted but, according to Affelder, with difficulty as he could only hear the loudest passages; Spohr called his leadership “uncertain and often ridiculous.”

The review of the concert in the influential Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung acclaimed the symphony a “triumph” that “fully deserved the loud applause and exceptionally warm reception that greeted it.” Yet such praise must be placed in perspective, as the same review hailed Wellington's Victory as “ingenious” and “leads one to conclude without hesitation that there is no work equal to it in the whole realm of tone-painting.” Indeed, the review in the Weiner Zeitung referred to the Seventh Symphony as a mere companion to the battle piece. Nowadays such comparisons seem absurd.  While Michael Steinberg defends the victorious conclusion as “concentrated” and “superbly composed,” and the remainder “naïve descriptive music” done with “a master’s sense of timing,” Wellington's Victory strikes most modern ears as a gimmicky pastiche intended to give sheltered concert-goers a safe and vicarious sonic taste of battle. Thus the first half of Beethoven’s score requires not only a main orchestra but two separate ones arrayed stereophonically to represent the English and French camps plus actual artillery. After each side presents its drum roll, trumpet fanfare and anthem, the combat begins and the score specifies the exact timing of 194 cannon shots (suitably balanced so that the English not only outweigh the French, 122 v. 72, but have the final 37) plus lengthy musket volleys from each side, all which must have been deafening within the confines of the concert hall and, in the context of the time, long before the advent of electronics and amplification, an overwhelming experience. While Michael Steinberg defends the victorious conclusion as “concentrated” and “superbly composed,” and the remainder “naïve descriptive music” done with “a master’s sense of timing,” Wellington's Victory strikes most modern ears as a gimmicky pastiche intended to give sheltered concert-goers a safe and vicarious sonic taste of battle. Thus the first half of Beethoven’s score requires not only a main orchestra but two separate ones arrayed stereophonically to represent the English and French camps plus actual artillery. After each side presents its drum roll, trumpet fanfare and anthem, the combat begins and the score specifies the exact timing of 194 cannon shots (suitably balanced so that the English not only outweigh the French, 122 v. 72, but have the final 37) plus lengthy musket volleys from each side, all which must have been deafening within the confines of the concert hall and, in the context of the time, long before the advent of electronics and amplification, an overwhelming experience.

Modern disparagement aside, Wellington's Victory served a noble purpose – to provide the strongest launch of any major Beethoven work, even if only through association. Audiences at the time heard the Seventh Symphony's buoyant exuberance and irresistible rhythm as an ideal companion to the battle piece and embraced it as a deeply-felt patriotic gesture and a welcome manifestation of the jubilant public mood. Yet while Czerny echoed the popular assumption that it was inspired by the recent military victories, Schindler points out that it had been completed long before those events occurred. Reflecting modern scholarship, David Wyn Jones asserts that it had been written between the fall of 1811 and the summer of 1812. In any event, the Battle Symphony drew unprecedented attention to its more serious companion.

As a measure of the Seventh’s huge popularity, by early 1816 its publisher had issued not only the full score and orchestral parts but arrangements for wind band, quartet, trio, piano duet and piano solo. Early critics, though, were less enamored. Aside from some nonsensical, hyperbolic slurs (Carl Maria von Weber said that Beethoven was ripe for the madhouse and Friedrich Weick called it the work of a drunkard), several critics claimed to find it disorganized and repetitious. Thus, one called it “a true mixture of tragic, comic, serious and trivial ideals which spring from one level to another without any connection [and] repeat themselves to excess.” Over a decade later, the London Harmonicum echoed: “Often as we have heard it performed, we cannot yet discover any design in it, neither can we trace any connection in its parts.”

Detractors who carped at its repetitiveness or found it disorganized clearly missed the very genius of the Seventh, which is unified by persistent and compelling rhythm. Indeed, no serious work before or since (so we're excluding Bolero) has relied so fully upon rhythm as its underlying principle. (And as for critics put off by the predominance of rhythm, it seems significant that rhythm has always been an element with far less appeal to sophisticates than to the populist masses, from medieval folk dance to jazz, disco and rap.) Detractors who carped at its repetitiveness or found it disorganized clearly missed the very genius of the Seventh, which is unified by persistent and compelling rhythm. Indeed, no serious work before or since (so we're excluding Bolero) has relied so fully upon rhythm as its underlying principle. (And as for critics put off by the predominance of rhythm, it seems significant that rhythm has always been an element with far less appeal to sophisticates than to the populist masses, from medieval folk dance to jazz, disco and rap.)  More enlightened analyses of the Seventh embrace and explore the wonders of its rhythm. Lewis Lockwood notes that, while rhythm is an element of nearly all music, here it is pushed into the foreground. And unlike in Beethoven’s Fifth, where the single opening motif recurs throughout the entire work, each movement here is animated by its own distinctive rhythm. Harking back to reactions to the premiere, Jones suggests that its untiring rhythmic articulation lends it an aura of a continuous celebration of joy. To Grove, the sheer “unflagging vigor,” as well as its “variety, life, color [and] elasticity,” create an impression of size and a mental image far disproportionate to its duration or emotional character. More enlightened analyses of the Seventh embrace and explore the wonders of its rhythm. Lewis Lockwood notes that, while rhythm is an element of nearly all music, here it is pushed into the foreground. And unlike in Beethoven’s Fifth, where the single opening motif recurs throughout the entire work, each movement here is animated by its own distinctive rhythm. Harking back to reactions to the premiere, Jones suggests that its untiring rhythmic articulation lends it an aura of a continuous celebration of joy. To Grove, the sheer “unflagging vigor,” as well as its “variety, life, color [and] elasticity,” create an impression of size and a mental image far disproportionate to its duration or emotional character.

Beyond its extraordinary sense of rhythm, other commentators credit the Seventh as romantic, in the sense of “swift and unexpected changes and contrasts, exciting the imagination to the highest degree and whirling it into new and strange regions” (Grove). Tovey expands on this notion of "exciting the imagination," while rationalizing the compulsion to “interpret” it in diverse ways, “insofar as romance is a term which, like humor, every self-respecting person claims to understand, while no two people understand it in quite the same way.” Others laud its innovative orchestration. Basil Lam calls the scoring “wonderful beyond explanation, unsurpassed anywhere for grandeur of sound,” even though this is achieved with the same modest orchestra familiar to Haydn and Mozart. Irving Kolodin cites in particular the finale as the first real orchestral piece ever written, in that instruments are not used for mere color but in keeping with the potential sonority of their inherent character. Features cited by Barry Cooper include the use of horns crooked in A, giving them an unusually high register, and drone basses, an offshoot of the Irish songs Beethoven had been commissioned to arrange at the time, in which such sustained harmony was common. William Drabkin cites the use of winds as a self-contained group rather than as an amplifier of string-dominated textures. Also remarkable, especially in the finale, is the way that Beethoven creates a heightened sense of activity within the continuity of a musical line by quickly and fluently passing phrases back and forth among instruments. The net result of all this, according to Drabkin, is that its originality lies not in the materials or proportions, which he finds quite conventional, but rather in the way Beethoven is able to control our perception of musical time. And this is achieved without any sense of respite from the constant energy and momentum – as many commentators have pointed out, similar to his shorter and simpler companion Symphony # 8 in F, Op. 93, there really is no slow portion at all, as the second movement specifies “allegretto” and even the trio is merely marked “assai meno presto” (much less quickly).

(Poco sostenuto – Vivace) – The first movement opens with a gesture that immediately announces its iconoclasm – a slow introduction nearly half as long as the remainder. (Poco sostenuto – Vivace) – The first movement opens with a gesture that immediately announces its iconoclasm – a slow introduction nearly half as long as the remainder.

The opening and theme of the first movement |

Leisurely symphony prologues were hardly novel – Haydn had used them, albeit briefly, in all but one of his final dozen “London” symphonies and Beethoven followed suit more expansively in his Second and Fourth Symphonies – but never with such length or import. Indeed, some commentators, including Grove, treat the slow introduction to the Seventh as a separate movement altogether. It opens with a vast chord ranging five octaves from a low A1 in the basses to a shrill a''' in the first flute. To Kolodin this symbolizes from the very outset a “spacing out of the orchestra in a rainbow of color” that opens our ears to vistas of musical thought unknown before then. Notwithstanding critics who found no sign of organic unity, the ensuing introduction contains a microcosm of the characteristics that will infuse the entire work – multiple levels of activity (emphatic chords, sustained notes, rapid motion), opposing progressions (descending bass downbeat figures v. ascending 16th note violin scales), gradual building toward and retreating from climaxes, juxtaposed pianissimo and fortissimo phrases, wind prominence, syncopation and, above all, the power of steadfast and obsessive rhythm. As Kinderman notes, the introduction “generates out of the most fundamental relationships of sound and time a propulsive rhythmic energy that is to inform the entire work.” Although long and far-reaching, it’s not a sprawling, independent conception but carefully and tightly structured, and serves to introduce multiple themes and materials that will be integral to the remainder. Yet, as McDonald observes, it keeps most of its latent energy locked up inside, and thus creates enormous suspense.

The acute sense of expectation fittingly peaks with a disarmingly simple but hugely effective transition to the ensuing vivace – it consists of nothing but 55 repeated E’s that at first tease and then coalesce into the modest but alluring three-note pattern in triplet time (a dotted eighth note, a sixteenth note and an eighth note) that will carry through to the end of the movement. (Noting that the repeated note is the top open violin string, Sigmund Spaeth intriguingly calls this “a suggestion of tuning fiddles,” as if to stress preparation for all that lies ahead.) Yet after four suspenseful minutes devoted to the introduction, rather than relieve the tension by having the vivace erupt dramatically, instead it emerges gently and playfully in the soft winds and only after a series of sforzando urgings do the strings at last proudly proclaim it fortissimo. The rest of the movement is in sonata form, but for Grove provides a prime example of Beethoven’s inventive genius – although the recapitulation presents the same materials as the exposition, it does so with “treatment, instrumentation and feeling all absolutely different.”

(Allegretto) – Like the opening movement of his Fifth Symphony, the Allegretto of the Seventh is an astounding example of how Beethoven could fashion a vast world from the humblest of materials. Historically, it was the most celebrated movement by far. (Allegretto) – Like the opening movement of his Fifth Symphony, the Allegretto of the Seventh is an astounding example of how Beethoven could fashion a vast world from the humblest of materials. Historically, it was the most celebrated movement by far.

The opening of the second movement |

The audience at the premiere clamored for it to be repeated, and Richard Freed reports that it was so notoriously popular throughout the following two decades that it sometimes was substituted for the slow movements of Beethoven’s earlier symphonies. Indeed, Berlioz rather disparagingly recalled that it was inserted into the Symphony # 2 “in order to help pass off the remainder.” Like the preceding movement, it immediately grabs our attention by opening with a chord, but with a difference – here, we begin with an inverted a-minor chord aptly described as “subtly unstable” (Steinberg) and “heart-rending” (Mann) that not only “casts a sudden mysterious chill over the memory of the preceding A-major coda” (Jack Deither) but is scored for winds alone and thus sounds “solitary and raw” compared to the prior warmth of bowed strings (Mann). The architecture of the entire movement is another remarkable illustration of the power of rhythm. Just consider the theme, which is melodically flat and harmonically static, and thus as inherently unappealing as could be. Rather, its appeal lies not in such conventional elements but in its compelling pulsation which persists throughout the entire movement, interrupted only briefly at key structural points before resuming – and expiring only at the very end, when that disconcerting opening wind chord is heard again as a closing bracket. To Speath the constant repetition of the same note emphasizes the inevitability of time itself. The tempo is significant – not a funereal adagio but a moderately-paced allegretto, which avoids any feeling of depression or sorrow but rather suggests an active melancholy, buffeted by focused thought. Nor is the constant repetition monotonous, since it keeps growing organically and interweaves counter-melodies, at first rising up through the instruments, next providing an ominous undertone to a lyrical section, then generating a fugato, and finally, after two forceful outbursts, fragmenting and descending into the primordial lower strings from which it first arose.

(Presto) – The third movement bursts out of the starting gate for a study in internal contrast. On the broadest level, it alternates a propulsive and rollicking presto section that bounds with ecstatic cheer and a trio that, despite its relative speed, projects stasis on a number of planes, (Presto) – The third movement bursts out of the starting gate for a study in internal contrast. On the broadest level, it alternates a propulsive and rollicking presto section that bounds with ecstatic cheer and a trio that, despite its relative speed, projects stasis on a number of planes,

The scherzo and trio of the third movement |

from its severely attenuated theme to a constant A-note drone that, as Drabkin notes, differs from a traditional bass pedal point as it is played by a variety of instruments, both above and below the main melodic line. But even within the presto, Beethoven buffets the pianissimo texture with sudden fortissimo stings and applies a number of volume swells that seem to vary the texture without departing from the insistent rapid pulse. Here, too, rhythm predominates, with the entire presto built upon the twin foundations of the rising and descending perky figures given at the very outset. Kinderman calls the trio “the still centre of the symphony,” and indeed it’s the only portion with a sense of respite from the rhythmic energy of the rest. Grove attributes its folk character to “a pilgrim’s hymn in common use in Lower Austria, and … an instance of Beethoven’s indifference to the sources of his materials when they were what he wanted and would submit to his treatment.”

Unlike a standard symphonic scherzo movement, comprising a scherzo, a trio and an abbreviated repeat of the scherzo (A-B-A), here both sections are repeated (A-B-A-B-A). McDonald suggests that this was to give the movement a dimension commensurate with the overall scale of the work. Yet, the first repetition of the scherzo presents a huge surprise, suppressing the ff stings of the initial appearance to the same pp whisper as the rest to lend it an entirely new and unsuspected sustained delicacy. In keeping with the nature of a scherzo (literally, a “joke”), Beethoven adds humorous touches, throwing off the regular musical periods with two-bar insertions, flavoring the trio with horn “burps” (Schumann’s term) and, above all, crafting an inspired ending, in which the music subsides to begin what promises to launch yet a third trio only to sour and then after a mere four bars plunge into a rapid five-note cadence.

(Allegro con brio) – The final movement is aptly described by Freed as “elemental fury unleashed,” (Allegro con brio) – The final movement is aptly described by Freed as “elemental fury unleashed,”

The opening and syncopated accompaniment of the finale |

by Jones as “aggressive vitality,” and by Lam as revealing “Beethoven’s ability to draw on the deepest primeval sources of pure energy.” Grove goes even further, asserting that while all Beethoven’s prior symphonic finales had dwelt within the bounds of convention (“Though strange, they contain nothing which can offend the taste, or hurt the feelings, of the most fastidious”), “here, for the first time, we find a new element, a vein of rough, hard, personal boisterousness” that reflects the composer’s “unbuttoned” attitude of no longer caring about affronts to social (or musical) expectation. McDonald calls the theme more of a “whirlwind figure” than a melody and asserts that it constantly assails us with a wall of fortissimo sound. Others note the resemblance of the theme to “Nora Creine,” an Irish folksong that Beethoven had recently set (WoO 154, # 8). The rhythms not only reach a peak of prominence but are remarkably complex. Just consider the accompaniment to the opening, after a brief call to attention (which, ironically, consists of more silence than sound) – although the natural accent of the theme falls heavily on the downbeat, the accompaniment consists of sforzando emphases on the third (brass and tympani) and fourth (winds) beats, so as to propel it forward with even greater compulsion. As Jones notes, it impresses not so much by its speed as by its muscular prowess; he cites in particular the impact of the violins and horns straining to play at the top of their registers. A profusion of secondary themes obsessively hammer home forceful figures, dotted accents and sustained notes, all reminiscent of the elements animating the prior movements but now concentrated and cohesively united. The movement, and the entire symphony, culminates in a final brickbat at customary expression – the first use of a startling triple forte (fff) in any of Beethoven’s scores.

Three particular concerns often guide interpretive approaches to the Seventh (as well as most orchestral music of the era). Most fundamental to any performance is tempo. Soon after the premiere of the Seventh, Beethoven obtained a metronome, perfected by none other than Maelzel, who replaced the initial design that had used a toothed wheel with a pendulum (but he may have lifted that idea from a Dutch inventor, Dietrich Winkel). According to Thayer, at first Beethoven rejected it as “silly stuff,” insisting that “one must feel the tempo.” Three particular concerns often guide interpretive approaches to the Seventh (as well as most orchestral music of the era). Most fundamental to any performance is tempo. Soon after the premiere of the Seventh, Beethoven obtained a metronome, perfected by none other than Maelzel, who replaced the initial design that had used a toothed wheel with a pendulum (but he may have lifted that idea from a Dutch inventor, Dietrich Winkel). According to Thayer, at first Beethoven rejected it as “silly stuff,” insisting that “one must feel the tempo.”

A Maelzel metronome

|

But by 1818 he came to consider a metronome “indispensible” and a welcome opportunity to give up the “nonsensical” Italian tempo designations (while retaining phrases describing the nature of a composition that suggest the emotional feeling to be conveyed). Ultimately, Beethoven appeared to arrive at a compromise, explaining on a song autograph that the numerical tempo must be observed for only the first few measures, “for feeling also has its tempo and cannot be expressed in this figure.” Perhaps that explains why Beethoven’s score is full of directives for internal dynamics (ranging from ppp to fff, plus sf, sfp, cresc., dimin.) and inflection (dolce, sempre, ten., slurs, phrasing) but no indication of tempo variation, which he apparently was willing to consign to the performers’ “feeling.” Thus, it seems wrong to assume, as some “purists” do, that respect for the score means adhering to rigid tempos, even if we assume that Beethoven’s opening specifications are accurate. (In that regard, Schindler points out that Beethoven had two metronomes with inconsistent markings, and scholars disagree as to which was the basis for the numerical tempos Beethoven specified to publishers of his earlier scores. Further valid questions have been raised as to the legitimacy of tempos that were assigned only years after composition and when Beethoven had arrived at a far different mental state.)

A second issue is the size of the ensemble that best conveys a score that is full of power yet demands fleet precision. The historically-informed approach generally is to assume an orchestra of modest dimensions, presumably typical of Beethoven’s day. Yet Drabkin notes that for a February 14, 1814 performance of the Seventh the composer left a memorandum specifying 18 first violins, 18 seconds, 14 violas, 12 celli, 7 basses and 2 contrabassoons (thus suggesting that all winds were to be doubled) – the approximate complement of a full modern symphonic orchestra (which would have to reinforce brass and winds yet further to match our louder strings). A related question is whether Beethoven, by now profoundly deaf, wrote within the practical limits of his time or on a more abstract, idealized level that transcends the resources he had at his disposal.

Robert Philips raises a third challenge by stressing the often overlooked point that early 20th century practice, as preserved in early recordings, is often wrongly dismissed as bloated and indulgent, yet was closer in time to Beethoven than to our own era and thus should not be disdained as an aberration requiring correction but rather as a manifestation of a venerable performance tradition. In particular, Philips catalogs more flexible tempos, greater acceleration, clearly defined tempo changes, more flexible and casual treatment of rhythmic detail, more restrained vibrato, more rubato (dislocating melody from accompanying rhythm) more portamento (sliding between notes) to clarify contrapuntal textures, and the use of individual string fingering in lieu of modern uniformity. He concludes that expressive irregularities and personal touches that strike us as decadent perhaps are far more authentic than the neat, clean simplicity that we tend to mistake as genuine. That, in turn, relegates any attempt to denounce the value of any particular interpretive approach to little more than a mere personal preference.

Of the literally hundreds of recordings of the Seventh, I’ve selected those that struck me as having particular historical or stylistic importance, plus some others that I've especially cherished. Please understand that these are merely my personal choices among the many dozens I’ve heard, and I’m sorry if I've overlooked your own favorites. Yet, for reasons that I hope will be evident, I make no apology for highlighting older recordings for their special qualities and fascination. Of the literally hundreds of recordings of the Seventh, I’ve selected those that struck me as having particular historical or stylistic importance, plus some others that I've especially cherished. Please understand that these are merely my personal choices among the many dozens I’ve heard, and I’m sorry if I've overlooked your own favorites. Yet, for reasons that I hope will be evident, I make no apology for highlighting older recordings for their special qualities and fascination.

- Coates, London Symphony Orchestra (HMV 78s, Pristine CD or download, 1921; 23' [abridged])

Coates’s Seventh remains remarkable for preserving interpretive traditions inherited from the 19th century. Relatively free of the improvisatory feeling of much of his superb discography, Coates’s tempos remain generally steady throughout each section, even though he does accelerate the allegretto at the first shift to A-major (bar 102).  Otherwise, he feels free to ignore Beethoven’s tempo indications, although hardly in the sense that most attach to them as being too fast. Thus, while his trio is taken at a leisurely 64 bars to the minute compared to Beethoven’s specification of 84, his opening poco sostenuto is a startling 90 beats to the minute versus Beethoven’s 69, and his finale is a frantic 92 bars v. 72, gaining extraordinary visceral excitement despite some lapses in articulation at the breakneck speed. It would be tempting to discount the extreme rapidity in order to fit the work onto six 78 rpm sides were it not for the similarly wild pacing of isolated movements of Coates’s Eroica and Jupiter recordings. Yet there were practical compromises, as all movements but the allegretto are cruelly cut – while the poco sustenuto introduction is intact, 95 bars are bypassed in the first-movement vivace, both the second scherzo and trio are omitted, and the entire recapitulation (bars 254-428) is excised from the finale. (The first of these cuts, coming at the mid-point of the vivace, is far more noticeable now than at the time, as it occurred between side changes, when continuity would have lapsed anyway.) Despite the severe restrictions of the acoustic recording process, the pickup is remarkably detailed, with inner voices clearly audible, the ensemble well-balanced and accents closely observed, although the dynamics are heavily compressed and the texture is distorted by the attenuation of overtones (making the flutes sound like slide-whistles) and the substitution of tubas for basses (with a more rasping, flatulent sonority – a routine studio practice of the time). Cuts and compromised fidelity aside, this remains a compelling, vivid account, as enjoyable today as when it first astounded listeners. Otherwise, he feels free to ignore Beethoven’s tempo indications, although hardly in the sense that most attach to them as being too fast. Thus, while his trio is taken at a leisurely 64 bars to the minute compared to Beethoven’s specification of 84, his opening poco sostenuto is a startling 90 beats to the minute versus Beethoven’s 69, and his finale is a frantic 92 bars v. 72, gaining extraordinary visceral excitement despite some lapses in articulation at the breakneck speed. It would be tempting to discount the extreme rapidity in order to fit the work onto six 78 rpm sides were it not for the similarly wild pacing of isolated movements of Coates’s Eroica and Jupiter recordings. Yet there were practical compromises, as all movements but the allegretto are cruelly cut – while the poco sustenuto introduction is intact, 95 bars are bypassed in the first-movement vivace, both the second scherzo and trio are omitted, and the entire recapitulation (bars 254-428) is excised from the finale. (The first of these cuts, coming at the mid-point of the vivace, is far more noticeable now than at the time, as it occurred between side changes, when continuity would have lapsed anyway.) Despite the severe restrictions of the acoustic recording process, the pickup is remarkably detailed, with inner voices clearly audible, the ensemble well-balanced and accents closely observed, although the dynamics are heavily compressed and the texture is distorted by the attenuation of overtones (making the flutes sound like slide-whistles) and the substitution of tubas for basses (with a more rasping, flatulent sonority – a routine studio practice of the time). Cuts and compromised fidelity aside, this remains a compelling, vivid account, as enjoyable today as when it first astounded listeners.

- Weingartner, London Symphony Orchestra (Columbia 78s, 1923-4; 32')

Although remembered nowadays for launching, even ahead of Toscanini, the modern “objective” style that typified (or, depending on your taste, ruined) 20th century interpretation (or lack thereof), Weingartner’s roots extended a generation deeper into the 19th century than Coates’s. Here, already 60 years old, he reaches back to his artistic origins to present a deeply romanticized, heavily inflected vision. Like Coates, he takes the opening faster, and the scherzo slower, than the score’s specifications (although his finale nearly matches Beethoven’s tempo). The most radical feature, which literally sets the pace for the vast majority of recordings that would follow, comes with the trio, which he paces at a mere 48 bars to the minute v. Beethoven’s 84 (and Coates’s 64). The result is a feeling not only of considerable repose but of comfort, perhaps in part because we have grown accustomed to hearing it that way. Weingartner may have been only the second conductor to record the Seventh, or the first to record it complete if we discount Coates’s condensation, but he also was the first to re-record it, in 1927 with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra as part of a complete set to commemorate the centennial of Beethoven’s death (and he would wax it yet a third time in 1936 with the Vienna Philharmonic in a less distinctive rendition). The 1927 remake is fascinating in comparison to the acoustic venture, as the scherzo is considerably faster (140 bars to the minute v. 116), thus providing a further reminder of the tradition of individual interpretation that could vary drastically from one performance to another (here bridged by a mere few years). the modern “objective” style that typified (or, depending on your taste, ruined) 20th century interpretation (or lack thereof), Weingartner’s roots extended a generation deeper into the 19th century than Coates’s. Here, already 60 years old, he reaches back to his artistic origins to present a deeply romanticized, heavily inflected vision. Like Coates, he takes the opening faster, and the scherzo slower, than the score’s specifications (although his finale nearly matches Beethoven’s tempo). The most radical feature, which literally sets the pace for the vast majority of recordings that would follow, comes with the trio, which he paces at a mere 48 bars to the minute v. Beethoven’s 84 (and Coates’s 64). The result is a feeling not only of considerable repose but of comfort, perhaps in part because we have grown accustomed to hearing it that way. Weingartner may have been only the second conductor to record the Seventh, or the first to record it complete if we discount Coates’s condensation, but he also was the first to re-record it, in 1927 with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra as part of a complete set to commemorate the centennial of Beethoven’s death (and he would wax it yet a third time in 1936 with the Vienna Philharmonic in a less distinctive rendition). The 1927 remake is fascinating in comparison to the acoustic venture, as the scherzo is considerably faster (140 bars to the minute v. 116), thus providing a further reminder of the tradition of individual interpretation that could vary drastically from one performance to another (here bridged by a mere few years).

- Wohllebe, Berlin State Opera Orchestra (Grammophon 78s, 1924; 32:40)

Very little seems to have been written about Walter Wohllebe, other than that he was a choral director who assisted Erich Kleiber at the Berlin State Opera in 1923. Yet he must have been held in sufficient esteem to have been chosen to lead the Seventh in the first integral set of Beethoven symphonies, alongside such luminaries as Klemperer, Fried, Pfitzner and Seidler-Winkler. As might be expected of a relatively unknown conductor (he may have led only one other recording, of the Wagner Tannhauser Overture) he adheres rather closely to the prescribed tempos but with two hugely notable exceptions: he begins the allegretto at a snail’s pace of only 50 beats per minute (v. Beethoven’s 76), but then (like Coates) jumps to 69 at the first A-major section, which he maintains throughout the rest, and (like Weingartner) takes the entire trio at a lugubrious 45 bars per minute, barely half of the prescribed 84. As a further individualistic touch, he adds a melodramatic flourish to the finale by prolonging the held notes and thus disrupting the insistent rhythm. Possibly in an effort to avoid sinking below the inherent noise floor of acoustic recordings, dynamics are nearly uniformly loud throughout, thus denying us the exhilarating surges and sforzando impacts of the score. The finale fits on a single side thanks to the same cut as Coates. The fidelity is indistinct and blurry, ironically due in part to the apparent use of real basses (and their unfortunate mid-range harmonic resonance) rather than the crisper tubas that most acoustic recordings substituted. Overall, the execution is rather indifferent and slipshod, but even that may preserve a valuable tradition of sorts – by draining much of the spirit and invoking the impression of an under-rehearsed pick-up band, we can empathize with early critics who found the work long and tedious, and to marvel with appreciation at Beethoven’s care in arranging its orchestration, textures and dynamics well beyond any reasonable expectations of the concert conditions of his time. other than that he was a choral director who assisted Erich Kleiber at the Berlin State Opera in 1923. Yet he must have been held in sufficient esteem to have been chosen to lead the Seventh in the first integral set of Beethoven symphonies, alongside such luminaries as Klemperer, Fried, Pfitzner and Seidler-Winkler. As might be expected of a relatively unknown conductor (he may have led only one other recording, of the Wagner Tannhauser Overture) he adheres rather closely to the prescribed tempos but with two hugely notable exceptions: he begins the allegretto at a snail’s pace of only 50 beats per minute (v. Beethoven’s 76), but then (like Coates) jumps to 69 at the first A-major section, which he maintains throughout the rest, and (like Weingartner) takes the entire trio at a lugubrious 45 bars per minute, barely half of the prescribed 84. As a further individualistic touch, he adds a melodramatic flourish to the finale by prolonging the held notes and thus disrupting the insistent rhythm. Possibly in an effort to avoid sinking below the inherent noise floor of acoustic recordings, dynamics are nearly uniformly loud throughout, thus denying us the exhilarating surges and sforzando impacts of the score. The finale fits on a single side thanks to the same cut as Coates. The fidelity is indistinct and blurry, ironically due in part to the apparent use of real basses (and their unfortunate mid-range harmonic resonance) rather than the crisper tubas that most acoustic recordings substituted. Overall, the execution is rather indifferent and slipshod, but even that may preserve a valuable tradition of sorts – by draining much of the spirit and invoking the impression of an under-rehearsed pick-up band, we can empathize with early critics who found the work long and tedious, and to marvel with appreciation at Beethoven’s care in arranging its orchestration, textures and dynamics well beyond any reasonable expectations of the concert conditions of his time.

- Strauss, Berlin State Opera Orchestra (Grammophon 78s, Koch CD, 1926; 32:15)

This first electrical recording of the Symphony # 7 serves to disprove a stereotype.  Perhaps due to his economical gestures, rapid tempos, obsession with fees and facetious pronouncements (conductors should never perspire; woodwinds should never be heard; the proper place for a conductor’s left [expressive] hand is in his waist-coat pocket), Richard Strauss tends to be remembered as a lazy and indifferent conductor. The generally reliable Harold Schonberg calls his records “disgraceful. … He rushes through the music with no force, no charm, no inflection and with a metronomic rigidity.” Yet nearly all Strauss’s recordings belie this damning portrayal. While most were of his own work, even his earliest (1917 acoustics of Till Eulenspiegel and Don Juan) crackle with excitement yet have plenty of repose in their central lyrical sections. (Peter Morse asserts that Strauss was late to the session and the first two sides of Don Juan in fact had been led by George Szell.) His 1926 Beethoven Seventh is generally calm but never bland, and has plenty of drama, from powerfully emphatic opening chords to setting up blazing endings of all but the allegretto, slowing in order to accentuate a final acceleration. If there is any “laziness” to Strauss’s conception, it lies in his rather formulaic tendency to link tempo and dynamics, so as to speed up for loud portions and slow down for softer ones. He even enlivens the normally steadfast finale with constant acceleration and deceleration. Strauss takes full advantage of the wider dynamic range of the then-new electrical recording process, although at the cost of some harsh sound, distortion and noise, inherent flaws of the Brunswick system which bypassed microphones for a more complex technology in which vibrations caused a mirror attached to a diaphragm to deflect a light ray onto a photocell. Unfortunately, while the rest of the symphony is presented complete, Strauss cuts the finale to fit on a single 78 rpm side and heightens the excitement by culminating in a wildly fast ending. (While the scherzo would seem the logical candidate for any necessary condensation, Strauss, despite his reputation as a speed demon, takes it at an abnormally slow pace, and his trio is barely half Beethoven’s specified tempo, so that the movement consumes a full two sides.) Any residual impression of Strauss as an uninspired conductor perhaps stems from the deep respect of one great composer for another. Perhaps due to his economical gestures, rapid tempos, obsession with fees and facetious pronouncements (conductors should never perspire; woodwinds should never be heard; the proper place for a conductor’s left [expressive] hand is in his waist-coat pocket), Richard Strauss tends to be remembered as a lazy and indifferent conductor. The generally reliable Harold Schonberg calls his records “disgraceful. … He rushes through the music with no force, no charm, no inflection and with a metronomic rigidity.” Yet nearly all Strauss’s recordings belie this damning portrayal. While most were of his own work, even his earliest (1917 acoustics of Till Eulenspiegel and Don Juan) crackle with excitement yet have plenty of repose in their central lyrical sections. (Peter Morse asserts that Strauss was late to the session and the first two sides of Don Juan in fact had been led by George Szell.) His 1926 Beethoven Seventh is generally calm but never bland, and has plenty of drama, from powerfully emphatic opening chords to setting up blazing endings of all but the allegretto, slowing in order to accentuate a final acceleration. If there is any “laziness” to Strauss’s conception, it lies in his rather formulaic tendency to link tempo and dynamics, so as to speed up for loud portions and slow down for softer ones. He even enlivens the normally steadfast finale with constant acceleration and deceleration. Strauss takes full advantage of the wider dynamic range of the then-new electrical recording process, although at the cost of some harsh sound, distortion and noise, inherent flaws of the Brunswick system which bypassed microphones for a more complex technology in which vibrations caused a mirror attached to a diaphragm to deflect a light ray onto a photocell. Unfortunately, while the rest of the symphony is presented complete, Strauss cuts the finale to fit on a single 78 rpm side and heightens the excitement by culminating in a wildly fast ending. (While the scherzo would seem the logical candidate for any necessary condensation, Strauss, despite his reputation as a speed demon, takes it at an abnormally slow pace, and his trio is barely half Beethoven’s specified tempo, so that the movement consumes a full two sides.) Any residual impression of Strauss as an uninspired conductor perhaps stems from the deep respect of one great composer for another.

- Stokowski, Philadelphia Orchestra (Victor 78s, Biddulph CD, 1927; 36')

Here we arrive at the first recording of the Seventh that requires few apologies or mental adjustment for its sheer sound.   Richly recorded only two years after introduction of the new electrical system, it’s beautifully played with confidence and a sheen that makes Strauss sound tentative and scrappy (and perhaps emphasizes the difference between an esteemed guest conductor and a permanent music director). Stokowski’s approach is unabashedly romantic, constantly adjusting the tempos to craft an organic voyage of vibrant, shifting feeling. The allegretto, in particular, emerges as a deeply emotional journey that takes its time (10:30 v. 7:05 for Weingartner, 7:20 for Coates, 8:20 for Wohlebbe and 9:25 for Strauss) to plumb depths impossible at any tempo near Beethoven’s and slows yet further for a heart-rending conclusion. The trio, too, overflows with profound feeling. Even in the faster sections, Stokowski constantly shapes phrases and leans into climaxes, taking full advantage of the extended dynamic range to create impassioned surges in the vivace and snarling and swirling his strings in the finale (and extending held notes to break the tempo for melodramatic effect). Richly recorded only two years after introduction of the new electrical system, it’s beautifully played with confidence and a sheen that makes Strauss sound tentative and scrappy (and perhaps emphasizes the difference between an esteemed guest conductor and a permanent music director). Stokowski’s approach is unabashedly romantic, constantly adjusting the tempos to craft an organic voyage of vibrant, shifting feeling. The allegretto, in particular, emerges as a deeply emotional journey that takes its time (10:30 v. 7:05 for Weingartner, 7:20 for Coates, 8:20 for Wohlebbe and 9:25 for Strauss) to plumb depths impossible at any tempo near Beethoven’s and slows yet further for a heart-rending conclusion. The trio, too, overflows with profound feeling. Even in the faster sections, Stokowski constantly shapes phrases and leans into climaxes, taking full advantage of the extended dynamic range to create impassioned surges in the vivace and snarling and swirling his strings in the finale (and extending held notes to break the tempo for melodramatic effect).

Ever the populist educator, Stokowski also recorded a companion “Outline of Themes” side in which he marvels at Beethoven’s creation of such a joyous work during a period of personal melancholy, repeats the cliché about the Seventh being a dance symphony and then announces and plinks out the major themes on a piano. While Stokowski’s lecture nowadays may strike us as shallow and condescending, Edward Johnson reminds us in his notes to the Biddulph CD reissue that this was the first American recording of the work, that radio and recordings were in their infancy and that many record-buyers would be hearing this symphony – and perhaps hearing of this symphony – for the very first time. That sobering thought prompts reflection on how much recordings have changed our culture from one in which the opportunity to hear a given work required the rare and taxing effort to attend a concert to one in which we have the luxury of summoning great performances at the push of a few buttons, although much may have been lost in the transition from an atmosphere demanding rapt attention to one that relegates music to superficial background.

Stokowski would record the Seventh again in 1958 with the Symphony of the Air (United Artists LP) and once more in 1973, his 91st year, near the very end of his extraordinarily prolific recording career, with the New Philharmonia Orchestra for Decca/London Phase Four. Exquisitely burnished, considerably slower and in superlative fidelity, it breathes with an autumnal perspective that lovingly transmutes impulsive energy into a smooth flow of tender affection. It also bears the dubious distinction of one of the very few stereo recordings of the Seventh to be truncated. According to the LP liner notes, “Maestro Stokowski has formed the opinion that the conventional Scherzo-Trio-Scherzo format is perfectly adequate and has subsequently omitted the second runthrough.” Even so, to all of us used to the five-part structure the abridgement comes as a surprise and is capped by an immediate leap into the finale – one more highly effective trick up the sleeve of an old master to compel us to focus our attention for a fresh experience.

- Toscanini, New York Philharmonic (Victor 78s, BMG CD, 1936; 34')

The ecstatic praise heaped on this 1936 recording is truly astounding:  “The Beethoven Seventh” (Kolodin); “The most perfect recording of any Beethoven symphony ever put on disc” (Records and Recordings, 1969); “Justifiably considered one of the greatest symphonic recordings ever made” (Harvey Sachs); “The standard against which all subsequent ones have been judged (and found wanting). … It remains as close to a perfect recording as one is likely to encounter this side of Elysium” (Mark Obert-Thorn). While I would hardly dare to pit my humble amateur taste against the weight of such expert authority, I just don’t hear it. Indeed, I wonder if their encomia were in part a function of the modern trend of distancing ourselves from the 19th century cult of personality in favor of a more “neutral” approach to the classics. In any event, Toscanini’s achievement here was to document a near-literal translation into sound of a score that perhaps demands (or tolerates) less “interpretation” than any of Beethoven’s other major works. His only significant departures from the score are an extremely somber poco sustenuto of 50 beats per minute v. Beethoven’s specification of 69 and an allegretto of 60 v. Beethoven’s 76; all other pacing is closely aligned with the composer’s. The method yields a striking result, enabling Toscanini to mold tempos, dynamics, textures and phrasing with a degree of subtlety that only a highly objective approach permits. Obert-Thorn reports that Toscanini had become annoyed by the start-and-stop mechanics of recording 78 rpm sides and had refused to approve efforts to record his concerts continuously on sound film, but here, at the end of his seven-year tenure with the New York Philharmonic, he agreed to momentary stops between sides, only long enough to switch the line inputs between turntables, and the result is a fine forward sweep of continuity. “The Beethoven Seventh” (Kolodin); “The most perfect recording of any Beethoven symphony ever put on disc” (Records and Recordings, 1969); “Justifiably considered one of the greatest symphonic recordings ever made” (Harvey Sachs); “The standard against which all subsequent ones have been judged (and found wanting). … It remains as close to a perfect recording as one is likely to encounter this side of Elysium” (Mark Obert-Thorn). While I would hardly dare to pit my humble amateur taste against the weight of such expert authority, I just don’t hear it. Indeed, I wonder if their encomia were in part a function of the modern trend of distancing ourselves from the 19th century cult of personality in favor of a more “neutral” approach to the classics. In any event, Toscanini’s achievement here was to document a near-literal translation into sound of a score that perhaps demands (or tolerates) less “interpretation” than any of Beethoven’s other major works. His only significant departures from the score are an extremely somber poco sustenuto of 50 beats per minute v. Beethoven’s specification of 69 and an allegretto of 60 v. Beethoven’s 76; all other pacing is closely aligned with the composer’s. The method yields a striking result, enabling Toscanini to mold tempos, dynamics, textures and phrasing with a degree of subtlety that only a highly objective approach permits. Obert-Thorn reports that Toscanini had become annoyed by the start-and-stop mechanics of recording 78 rpm sides and had refused to approve efforts to record his concerts continuously on sound film, but here, at the end of his seven-year tenure with the New York Philharmonic, he agreed to momentary stops between sides, only long enough to switch the line inputs between turntables, and the result is a fine forward sweep of continuity.

To my ears, the Philharmonic set sounds bland when compared to Toscanini’s concert recordings of the era. Thus, while the timings are nearly identical, a 1935 BBC Symphony Orchestra concert (BBC Music CD) is marginally more dramatic, with more urgent articulation and inflection and a somewhat quicker allegretto. As Sachs points out, the excellence and synchronization of conductor and orchestra are remarkable, as they had only worked together for two weeks at that point. Even more intense is a 1939 concert with the NBC Symphony Orchestra (Music and Arts CD), which substitutes precision for atmosphere, abetted by a sharply detailed recording with crisp timpani, winds and brass in lieu of the smoother blend and dull thuds of the Philharmonic studio recording. And tantalizing fragments from an April 1933 Philharmonic concert, despite miserable sound, evidence a tightly focussed yet pliant approach. In comparison, Toscanini’s highly-regarded NBC 1951 studio remake (RCA LP, BMG CD) sounds rather tired, with some “lazy” trumpet figures falling behind the beat, although it is partly redeemed by even stronger timpani-fueled climaxes. Any of the Toscanini outings exemplify a dedication to presenting the score with only minimal injection of the performer’s personality. Whether that is the epitome of integrity or a lack of imagination is, for me at least, an open question. In any event, what was once a daring pioneering approach has since become the norm and deserves to be remembered on that basis, even if its sense of boldness has long since dissipated.

- Furtwangler, Berlin Philharmonic (DG or Music and Arts CD, November 3, 1943 concert; 37½')

A simplistic myth contrasts Toscanini and Furtwangler as inhabiting the extreme opposite poles of music interpretation.  Yet in Beethoven, and especially here, it seems warranted. While Toscanini presents the Symphony # 7 as pure music, Furtwangler delves deep beneath the surface to craft a radical and profoundly personal rethinking that seeks eternal truth where others are content with lyrical grace and invocations of the dance. As with so many of his interpretations, his most intense reading is preserved in a Berlin Philharmonic concert during World War II. Consider the opening – each of the tutti chords is marked staccato, indicating a sharp attack, but under Furtwangler they emerge rough and blurred, struggling to overcome the stifling silence and heralding his vision of the entire work as an elemental metaphysical struggle between energy and fatigue, light and dark, motion and stasis – a heavy, dark and brooding universe far removed from any notion of classical balance or delight, much less “the dance.” Indeed, the ensuing vivace, while taken on average at the specified pace, assumes a wholly different character as the basses growl with menace, the tympani thunder with power, the horns bray in dire warning and the whole ensemble surges ahead and then grinds to a halt on a precipice of the unknown before resuming more as a tentative searching question than an affirmative resolute conviction, pulled back to earth before it can truly soar. The opening chord of the allegretto is held for eight seconds – over twice its notated length – and also heralds the ensuing movement that is dominated by a mournful yet unstable undercurrent, smoothly gliding between 27 and 36 beats per minute (v. Beethoven’s 76). The scherzo is suitably fast but thick, underlining the difference between tempo and texture. The feeling of insecurity returns in the finale, also taken at the prescribed pace, but with huge timpani rolls, abrasive trumpet accents and insistent outbursts, sounding far more desperate than joyous. He ends with an enormous acceleration that seems more a cathartic emergence from tragedy than a triumphant outcome. Indeed, his entire interpretation invests this ostensibly festive work with a pervasive sadness that adds a fascinating level of meaning to challenge our expectations. (Furtwangler’s other extant recordings of the Seventh – a 1948 Stockkholm Philharmonic concert, a 1950 Vienna Philharmonic EMI studio recording, a 1953 Berlin Philharmonic concert and a 1954 Vienna Philharmonic concert – all follow the same general scheme, but without the intense focus of this wartime concert.) Yet in Beethoven, and especially here, it seems warranted. While Toscanini presents the Symphony # 7 as pure music, Furtwangler delves deep beneath the surface to craft a radical and profoundly personal rethinking that seeks eternal truth where others are content with lyrical grace and invocations of the dance. As with so many of his interpretations, his most intense reading is preserved in a Berlin Philharmonic concert during World War II. Consider the opening – each of the tutti chords is marked staccato, indicating a sharp attack, but under Furtwangler they emerge rough and blurred, struggling to overcome the stifling silence and heralding his vision of the entire work as an elemental metaphysical struggle between energy and fatigue, light and dark, motion and stasis – a heavy, dark and brooding universe far removed from any notion of classical balance or delight, much less “the dance.” Indeed, the ensuing vivace, while taken on average at the specified pace, assumes a wholly different character as the basses growl with menace, the tympani thunder with power, the horns bray in dire warning and the whole ensemble surges ahead and then grinds to a halt on a precipice of the unknown before resuming more as a tentative searching question than an affirmative resolute conviction, pulled back to earth before it can truly soar. The opening chord of the allegretto is held for eight seconds – over twice its notated length – and also heralds the ensuing movement that is dominated by a mournful yet unstable undercurrent, smoothly gliding between 27 and 36 beats per minute (v. Beethoven’s 76). The scherzo is suitably fast but thick, underlining the difference between tempo and texture. The feeling of insecurity returns in the finale, also taken at the prescribed pace, but with huge timpani rolls, abrasive trumpet accents and insistent outbursts, sounding far more desperate than joyous. He ends with an enormous acceleration that seems more a cathartic emergence from tragedy than a triumphant outcome. Indeed, his entire interpretation invests this ostensibly festive work with a pervasive sadness that adds a fascinating level of meaning to challenge our expectations. (Furtwangler’s other extant recordings of the Seventh – a 1948 Stockkholm Philharmonic concert, a 1950 Vienna Philharmonic EMI studio recording, a 1953 Berlin Philharmonic concert and a 1954 Vienna Philharmonic concert – all follow the same general scheme, but without the intense focus of this wartime concert.)

- Mengelberg, Concertgebouw Orchestra of Amsterdam (Music and Arts CD, Pristine download, 1940 concert; 39½')

It would be tempting to say that Mengelberg followed firmly in Furtwangler’s footsteps, had his career not begun 15 years earlier. Chronology aside, though, their approaches to the Symphony # 7 are strikingly similar, full of rolled opening chords, constantly variable tempos and thick tympani-fueled climaxes. They finally part company in the trio, which Mengelberg takes at an astoundingly protracted 40 beats per minute. But even that is a mere average, as the tempo constantly shifts and at times grinds to a near-halt, after which the scherzo snaps in with startling impact. Indeed, the effect of both the pacing and the instability is to deny any feeling for a downbeat, which dissolves into a state of suspended time that is as far from the rudiments of the dance, with its reliably consistent tempo, as can be. From that point forward, any possibility of restoring elation through the finale is irreparably lost. Indeed, Mengelberg’s finale is even darker than Furtwangler’s, owing in substantial part to the recording that emphasizes the bass-heavy sonic anchor to keep the entire work not only earth-bound but incapable of even the momentary flights of escape that his surges of onrushing power might otherwise allow. Rather, the impression is one of hesitation and uncertainty. Like Furtwangler, Mengelberg transforms the symphony into something wholly distinctive. had his career not begun 15 years earlier. Chronology aside, though, their approaches to the Symphony # 7 are strikingly similar, full of rolled opening chords, constantly variable tempos and thick tympani-fueled climaxes. They finally part company in the trio, which Mengelberg takes at an astoundingly protracted 40 beats per minute. But even that is a mere average, as the tempo constantly shifts and at times grinds to a near-halt, after which the scherzo snaps in with startling impact. Indeed, the effect of both the pacing and the instability is to deny any feeling for a downbeat, which dissolves into a state of suspended time that is as far from the rudiments of the dance, with its reliably consistent tempo, as can be. From that point forward, any possibility of restoring elation through the finale is irreparably lost. Indeed, Mengelberg’s finale is even darker than Furtwangler’s, owing in substantial part to the recording that emphasizes the bass-heavy sonic anchor to keep the entire work not only earth-bound but incapable of even the momentary flights of escape that his surges of onrushing power might otherwise allow. Rather, the impression is one of hesitation and uncertainty. Like Furtwangler, Mengelberg transforms the symphony into something wholly distinctive.

The pioneers clearly felt no qualms against crafting a personal statement. Their influence is felt in some more modern recordings that hold particular appeal for those familiar with the work in more standard presentations. The following examples list the actual timing and, where appropriate for a more meaningful comparison, an estimate in brackets of the result had repeats been omitted. Admittedly, timing alone is a superficial way to characterize an entire performance. Yet in a work such as the Seventh, in which rhythm is a primary driving force, it can be a significant signpost of overall approach. The pioneers clearly felt no qualms against crafting a personal statement. Their influence is felt in some more modern recordings that hold particular appeal for those familiar with the work in more standard presentations. The following examples list the actual timing and, where appropriate for a more meaningful comparison, an estimate in brackets of the result had repeats been omitted. Admittedly, timing alone is a superficial way to characterize an entire performance. Yet in a work such as the Seventh, in which rhythm is a primary driving force, it can be a significant signpost of overall approach.

- Scherchen, Italian Swiss Radio Orchestra (various Japanese CDs, 1965 Lugano concert; 31:40) – Of all the Sevenths I’ve encountered,

after Coates, this is the only one that beats most of Beethoven’s own tempos (although not by much and not in the allegretto and trio – “for the record” his average tempos compared to Beethoven’s are: I: 78 v. 69 and 106 v. 104; II: 68 v. 76; III: 136 v. 132 and 66 v. 84; IV: 78 v. 72). Interestingly, Scherchen’s conventional 1951 Vienna studio recording (Westminster LP) was a full four minutes slower, so this testifies to either his radical rethinking of the work or the spontaneous exhilaration of a concert. (Probably the latter – in the same series he tore through the Pastoral in less than 35 minutes but languished in the Eroica for nearly 50.) It’s certainly worth hearing, if only as a basis for comparison with others, but to my ears it emerges as rushed and even frantic, with ragged playing and frayed ensemble that suggest that Beethoven set his tempos at the outer limit of even the most accomplished players’ ability. after Coates, this is the only one that beats most of Beethoven’s own tempos (although not by much and not in the allegretto and trio – “for the record” his average tempos compared to Beethoven’s are: I: 78 v. 69 and 106 v. 104; II: 68 v. 76; III: 136 v. 132 and 66 v. 84; IV: 78 v. 72). Interestingly, Scherchen’s conventional 1951 Vienna studio recording (Westminster LP) was a full four minutes slower, so this testifies to either his radical rethinking of the work or the spontaneous exhilaration of a concert. (Probably the latter – in the same series he tore through the Pastoral in less than 35 minutes but languished in the Eroica for nearly 50.) It’s certainly worth hearing, if only as a basis for comparison with others, but to my ears it emerges as rushed and even frantic, with ragged playing and frayed ensemble that suggest that Beethoven set his tempos at the outer limit of even the most accomplished players’ ability.

- Celibidache, Munich Philharmonic (EMI CD, 1989; 43') – At the other extreme, as is often the case, Celibidache weighs in with the slowest of all the recordings I’ve heard. In keeping with his Zen beliefs, both drama and animation are purged. But while I greatly admire most of his late work as revelatory (especially in Bruckner, Brahms, and the other Beethoven symphonies), here the result seems perverse. Drained of its essential energy, his Seventh emerges as stodgy and grueling. Although beautifully played – the opening chords materialize and recede with exceptional ease – we seem to miss the proverbial forest for the trees – a microscopic examination and dissection rather than a study of a thriving organism.

- Bernstein, Boston Symphony (DG CD, 1990, 45' [41']) – I’m including this

only because of its apparently even slower timing, but: it includes first- and third-movement repeats and applause (about 4' total), Bernstein was fatally ill (it was his last public appearance), the execution sounds listless and fatigued, and reportedly he collapsed during the scherzo although the orchestra covered valiantly. More representative of the late stage of his art was a vibrant 1978 Vienna Philharmonic concert (DG CD, 1980; 39' [36']) or, for a bracing dose of his earlier vigor (and stamina – it includes the finale repeat, rarely heard at the time), his 1964 NY Philharmonic record (Columbia LP, Sony CD; 42' [37']), itself a remake of a 1959 LP. only because of its apparently even slower timing, but: it includes first- and third-movement repeats and applause (about 4' total), Bernstein was fatally ill (it was his last public appearance), the execution sounds listless and fatigued, and reportedly he collapsed during the scherzo although the orchestra covered valiantly. More representative of the late stage of his art was a vibrant 1978 Vienna Philharmonic concert (DG CD, 1980; 39' [36']) or, for a bracing dose of his earlier vigor (and stamina – it includes the finale repeat, rarely heard at the time), his 1964 NY Philharmonic record (Columbia LP, Sony CD; 42' [37']), itself a remake of a 1959 LP.

- Asahina, New Japan Philharmonic (Fontec CD, 1989 Tokyo concert; 43½' [38']) – Only in part is this remarkable for its novelty – a thoroughly convincing rendition of German music by a Japanese conductor and orchestra. Yet, perhaps it’s not surprising coming from a Bruckner specialist and Furtwangler devotee. Superbly played with fine balances, polished phrasing and smooth dynamics, and with all repeats taken, it unfolds with assured logic and an insistent, if patient, rhythmic drive. There may be little joy in the scherzo, but a ravishing allegretto more than compensates.

- Klemperer, Philharmonia (EMI LP and CD, 1955 – 38½'; and 1960 – 41½') – Klemperer’s granitic, monumental approach to the classics in the final phase of his career could illuminate nearly any work. Even his 29-minute unfolding of Beethoven’s First serves to endow that youthful foray into the symphony with historical perspective so as to underline its serious aspect and thus places it firmly in perspective as a herald of the more profound works that were to come.