|

|

George Gershwin's Concerto in F was the last successful attempt to meld serious and pop music. In this article, we consider the background, its relation to jazz, its remarkable structure, Gershwin's own performing style and some of its most significant and historically-important recordings. Finally, we list some sources of further information about the work. |

|

When the definitive history of 20th century music is finally written, the most distressing trend surely will be the irreparable rift between popular and serious music. the most distressing trend surely will be the irreparable rift between popular and serious music.

In the late 1800s, tunes from the latest operas were whistled in the streets, but as the 20th century wore on pop and art music parted ways. Ranging through big band, show tunes, rock, punk, rap and beyond, pop music retained its its mass appeal while remaining true to its cultural vision. Serious music, though, bifurcated into two irreconcilable branches. Anachronistic imitations of 19th century models attracted mass audiences with simple taste, but merely dwelled in the past, bringing centuries of artistic evolution to a halt. Meanwhile, the vast majority of listeners shunned deeply challenging, credible progressive music, shorn of familiar anchors of melody, harmony, rhythm and structure. Neither served the cause of esthetic progress.

One of the last efforts to bridge the widening gap arose with George Gershwin, whose most conscious attempt to graft his brilliant gift as a pop tunesmith onto traditional classical form was his 1926 piano concerto, known simply as the Concerto in F.

The Concerto in F came at a propitious time. As Joan Peyser has pointed out, classical composers were facing the challenge of how to structure music after believing that they had finally exhausted the possibilities of tonality, upon which the prior centuries of music had been based. Arnold Schoenberg had just abandoned tonality altogether in favor of a new twelve-tone method of organization, while Igor Stravinsky’s neoclassicism took the opposite tack by plunging back into the past for renewed inspiration. Gershwin followed a middle path, building on popular music idioms of the day.

The Concerto in F came at a propitious time. As Joan Peyser has pointed out, classical composers were facing the challenge of how to structure music after believing that they had finally exhausted the possibilities of tonality, upon which the prior centuries of music had been based. Arnold Schoenberg had just abandoned tonality altogether in favor of a new twelve-tone method of organization, while Igor Stravinsky’s neoclassicism took the opposite tack by plunging back into the past for renewed inspiration. Gershwin followed a middle path, building on popular music idioms of the day.

Gershwin’s path to this juncture was swift if improbable. He had left high school for Tin Pan Alley, where he worked as a pianist plugging sheet music, while moonlighting as an accompanist and dabbling in composition. Having absorbed the writing and performing styles of his time, at age 20 he soared to fame with “Swanee,” a mega-hit for Al Jolson, soon became established as a prolific and superbly talented songwriter and graduated to Broadway where he wrote a dozen shows by age 25. Commissioned by Paul Whiteman for a marathon “Experiment in Modern Music” concert on February 12, 1924, his Rhapsody in Blue was a sensation, suggesting that his range extended beyond the pop confines of his initial fame.

Self-Portrait (1934) |

That, in turn, apparently stoked his confidence and kindled his ambitions - he announced his next project as “a jazz opera with a Negro subject” (but that would come to fruition a decade later as his masterwork Porgy and Bess). A suitable opportunity to prove himself as a serious composer soon came in a commission for a piano concerto from Walter Damrosch and the New York Symphony Society, to be given in seven concerts featuring Gershwin as the soloist. Gershwin accepted the challenge, in part to prove that the success of his Rhapsody in Blue was no fluke: “Many persons had thought that the Rhapsody was only a happy accident. Well, I went out, for one thing, to show them that there was more where that had come from. I made up my mind to do a piece of absolute music. The Rhapsody was a blues impression. The Concerto would be unrelated to any program.”

Gershwin then left for London to open a new show, later claiming that he brought along “four or five books on musical structure to find out what the concerto form really was.” Having been issued a week before the premiere, this statement may have been mere puffery for publicity purposes to boost the apparent magnitude of his achievement. Indeed, as Edward Jablonsky notes, although he may have been self-conscious over his lack of conservatory training, Gershwin in fact had studied composition. In any event, Gershwin took three months to write his concerto as a two-piano score and another to orchestrate it.

Gershwin completed the full score on November 10. Later that month he held a trial audition. He later recalled: “My greatest musical thrill? The time that I first heard my Concerto in F played by an orchestra.

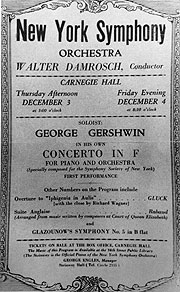

Program of the Premiere |

That was my first orchestration. Two weeks before the concerto was publically presented … I hired an orchestra of 50 musicians with whom I played the piece in the Globe Theater. That was an experience I’ll never forget. … You can imagine my delight when it sounded just as I had planned.” Although Damrosch claimed that he “didn’t know what to do with this strange work,” the Symphony Society’s December 3, 1925 premiere, before an audience packed with musical elite, was a huge success. Composer and orchestra toured the Concerto for the rest of the year.

Olin Downes opined in the New York Times that the Concerto was “a dubious experiment” and that Gershwin had “neither the instinct nor the technical equipment to be at ease in … a work of symphonic dimensions.” Lawrence Gilman, in the New York Tribune, contrasted it with the Rhapsody and claimed to “weep over the lifelessness of its melody and harmony, so derivative, so stale, so inexpressive.” John Struble points out that such mainstream critics seized upon the manifest deficiencies in Gershwin’s formal technique by judging him with the criteria of European art music, but that Gershwin’s perspective was far different – while other composers had been exposed to folk and vernacular music, Gershwin was a seasoned, professional writer of songs, which comprised his native language and became the frame of reference from which he attacked all compositional projects. Thus he was the first American to be able to approach classical music as part of a great continuum, and to regard pop not as cultural slumming but in a wholehearted embrace among equals.

Other critics seized upon the novelty – and patriotism – of this approach. Thus, Carl Engel in Musical Quarterly hailed it as “of a newness to be found nowhere except in these United States,” and for Beverly Nichols, an English critic, it conjured a vision “that the whole of America was blossoming into beauty before me.” Henry Osgood proclaimed: “He gave us something really new in music.

1925 – on the cover of Time! |

Not more than a dozen composers out of the hundreds on the honor list since composing began have succeeded in doing that.” Samuel Chotzinoff: “But all his shortcomings are nothing in the face of the one thing he alone of all those writing the music of today possesses. He alone actually expresses us. He is the present with all its audacity, impertinence, its feverish delight in its motion, its lapses into rhythmically exotic melancholy. He writes without the smallest hint of self-consciousness, and with unabashed delight in the stridency, the gaucheries, the joy and excitement of life as it is lived right here and now.” And in a final dig at conservative critics, Chotzinoff hailed Gershwin as “an instinctive artist who has that talent for the right manipulation of the crude material he starts out with that a lifelong study of form and harmony and counterpoint and fugue never can give to one who is not born with it.”

Perhaps the most remarkable appreciation came in 1938 as a posthumous tribute from none other than Arnold Schoenberg, arguably the most influential composer of the twentieth century, but whose rigid formal esthetics were diametrically opposed to Gershwin’s free-flowing inspiration:

Gershwin is an artist and a composer – he expressed musical ideas, and they were new, as is the way he expressed them. … An artist is to me like an apple tree. When the time comes, whether it wants to or not it bursts into bloom and starts to produce apples. … Serious or not, he is a composer, that is, a man who lives in music and expresses everything, serious or not, sound or superficial, by means of music, because it is his native language. … What he has done with rhythm, harmony and melody is not merely style. It is fundamentally different from the mannerism of many a serious composer [who writes] a superficial union of devices applied to a minimum of ideas. … The impression is of an improvisation with all the merits and shortcomings appertaining to this kind of production. … He only feels he has something to say and he says it.

Critics at the time referred to the new work as a jazz concerto. Gershwin rejected the label, stating that he had merely “attempted to utilize certain jazz rhythms worked out along more or less symphonic lines,” even though he noted that his “intervals” (presumably referring to harmonies and melodies) were derived from and peculiar to those jazz rhythms. Indeed, Gershwin considered the jazz of his time to be blatant and crude – “noisy, boisterous and even vulgar” – and looked forward to the time when it would emerge not as a predominant genre but would be absorbed into the great realm of musical tradition as “but one element in a great whole which at last will give a worthy musical expression to the spirit which is America.”

Critics at the time referred to the new work as a jazz concerto. Gershwin rejected the label, stating that he had merely “attempted to utilize certain jazz rhythms worked out along more or less symphonic lines,” even though he noted that his “intervals” (presumably referring to harmonies and melodies) were derived from and peculiar to those jazz rhythms. Indeed, Gershwin considered the jazz of his time to be blatant and crude – “noisy, boisterous and even vulgar” – and looked forward to the time when it would emerge not as a predominant genre but would be absorbed into the great realm of musical tradition as “but one element in a great whole which at last will give a worthy musical expression to the spirit which is America.”  Rather, he viewed jazz in a broader sense of “the spontaneous expression of the nervous energy of modern American life” that “expresses something vital in American life.” He viewed it as a “a powerful American folk music – not the only one but a very powerful one that is probably in the blood and feeling of the American people more than any other style of folk music” and therefore America’s greatest contribution to musical art. Rather, he viewed jazz in a broader sense of “the spontaneous expression of the nervous energy of modern American life” that “expresses something vital in American life.” He viewed it as a “a powerful American folk music – not the only one but a very powerful one that is probably in the blood and feeling of the American people more than any other style of folk music” and therefore America’s greatest contribution to musical art.

Just what is jazz anyway? Attempts to define it are so varied as to be more confusing than helpful. Even the individual elements that often recur hardly seem distinctive. Thus, we read of the innovative use of “blue” notes (that is, expressive notes between the standard diatonic tones), but this was standard practice in the centuries before equal temperament. Similarly, syncopation was a staple of renaissance dance music. Improvisation was expected of soloists in the cadenzas of concertos. And emphasis on solo work would seem to exclude big band arrangements and Duke Ellington’s orchestrations. Perhaps the only practical attempt to define jazz is the one that its own artists tend to offer, along the lines of “You know it when you hear it.”

That the Concerto in F was considered to be jazz was more a reflection of a massive cultural divide of its time than any intrinsic factor. Although there were some prominent and influential white jazz artists – Bix Biederbecke, Benny Goodman – the far more significant black jazzmen – King Oliver, Jellyroll Morton, Louis Armstrong – were largely unknown, whether intentionally or out of sheer ignorance. Thus, the first book devoted to jazz – Henry O. Osgood’s 1926 So This is Jazz – devoted entire chapters to Irving Berlin, Paul Whiteman and Gershwin (whom he dubbed the leading exponent) but referred to black musicians only in a single footnote. Charles Hamm attributes this perception of jazz as a largely white phenomenon to its exposure through the mass media filter of records and radio. Hamm posits that in order to be taken seriously music had to be seen as “progressive” in some way, but since there was nothing new in Gershwin’s harmonic, melodic or structural techniques his supporters seized upon its superficial “jazz” qualities, such as those “blue” notes.  He further asserts a social/political motive – by combining the standard symphonic vocabulary with pop and ethnic styles Gershwin was an ideal vehicle to advance the democratization of serious music, which, as we have noted, was increasingly alienating audiences and desperately needed some means to reverse that trend. Constant Lambert hails Gershwin as a pioneer in the process of incorporating other genres, especially those cultivated by African-Americans, into mainstream music, a process that he considers the most important musical development of the 20th century. He further asserts a social/political motive – by combining the standard symphonic vocabulary with pop and ethnic styles Gershwin was an ideal vehicle to advance the democratization of serious music, which, as we have noted, was increasingly alienating audiences and desperately needed some means to reverse that trend. Constant Lambert hails Gershwin as a pioneer in the process of incorporating other genres, especially those cultivated by African-Americans, into mainstream music, a process that he considers the most important musical development of the 20th century.

Ironically, these same considerations led the cultural gatekeepers to erect twin formidable cultural hurdles that Gershwin was forced to confront and overcome. As Joseph Horowitz points out, as a Brooklyn Jew Gershwin was considered “rootless” and thus lacking the essential artistic and social traditions from which great music was deemed to stem. At the same time, by dabbling in jazz (or at least the mainstream racist perception of jazz), he became identified with what was considered a primitive and degenerate form of real music. Horowitz concludes that Gershwin ultimately was redeemed by the “culture of performance” – once listeners set aside their prejudices, they found themselves delighted by his achievements. Gershwin himself anticipated this: “I am one of those who honestly believes that the majority has much better taste and understanding … than it is credited with having. It is not the few knowing ones whose opinions make any work of art great; it is the judgment of the great mass that finally decides.”

In any event, public attitudes soon evolved. By 1930, Isaac Goldberg’s Tin Pan Alley – a Chronicle of the American Pop Music Racket signaled a shifting recognition of jazz as “essentially an American development of Afro-American thematic material. … Its fundamental rhythm and its characteristic melody derive from the Negro. … The commercialization of Gotham quickly denatured the outlook for white consumption.” Nowadays, in André Barbera’s phrase, we accept the “recognition of Black origins rather than fundamentally European with special touches and timbres.” Indeed, modern writings on jazz barely even mention Gershwin, and then usually only in the context of his songs serving as inspiration for jazz treatment. (Aside from their catchy melodies, whose repeated notes Constant Lambert likens to the flattening of melody in jazz improvisations, musicians are attracted by the challenge of keeping up with the extraordinary pace of harmonic activity.  Thus Stephen Gilbert identifies 67 chord changes in the 28-bar refrain of Gershwin’s song “Beginner’s Luck.”) In retrospect, it seems incredible that Whiteman got away with billing himself as the “King of Jazz” when, in Edward Jablonski’s view, all he did was dress “obvious devices used by real jazzmen … in tricky big-band arrangements and perform them with missionary zeal.” As for Whiteman's huge success in the "naughty" 'Twenties that prided itself on breaking down social constraints, Jablonsky suggests: “There was something titillating about dancing to the kind of music that may have originated in brothels.” Thus Stephen Gilbert identifies 67 chord changes in the 28-bar refrain of Gershwin’s song “Beginner’s Luck.”) In retrospect, it seems incredible that Whiteman got away with billing himself as the “King of Jazz” when, in Edward Jablonski’s view, all he did was dress “obvious devices used by real jazzmen … in tricky big-band arrangements and perform them with missionary zeal.” As for Whiteman's huge success in the "naughty" 'Twenties that prided itself on breaking down social constraints, Jablonsky suggests: “There was something titillating about dancing to the kind of music that may have originated in brothels.”

Other attempts to base “serious” music on jazz seem wanting in comparison to Gershwin. Large-scale works seem to lack the full measure of integration of the Concerto in F. Thus, Aaron Copland’s 1924 Piano Concerto seemingly draws a distinction between its two elements, beginning with a calm, if astringent, introduction steeped in tradition from which the soloist erupts with a variety of rhythmic and intervallic invocations of jazz. Even with the benefit of decades of maturity, Rolf Liebermann’s 1954 Concerto for Jazz Band and Symphony Orchestra features jump, blues, boogie-woogie and mambo sections played by a jazz combo, separated by staid orchestral interludes. Despite their sporadic surges of energy, both works seem self-conscious in asserting their materials, and lack the melodic ease, flowing structure and natural attitude of the Concerto in F.

Far more credible are less pretentious, chamber-proportioned works. Darius Milhaud frequented Harlem jazz venues. His 1923 ballet La Création du Monde for 19 instruments has a pastoral opening (underlined by rumbling, impatient drums) and then, like Gershwin, applies the root elements of jazz to a classical context, even including fugues, leading to a noisy, dissonant climax, all evoking the spirit, if not the authentic sounds, of jazz. Igor Stravinsky, though, claimed never to have heard jazz, but rather based his conception strictly upon sounds he imagined from sheet music. Perhaps that accounts for the rather dry, academic quality of his early playful, intensely concentrated rhythmic explorations – a 4½ -minute 1918 Ragtime for Eleven Instruments and his 3-minute 1919 Piano-Rag-Music – while his nostalgic 1945 Ebony Concerto emulates the structure, if not the heady sense of joyous liberation, of the Concerto in F, with three brief movements comprising a rhythmic sonata, somber blues and busy, energetic variations. (Although often cited as a jazz work, his hour-long 1918 playlet Histoire du Soldat for seven instruments and a narrator reflects the disillusionment and alienation of the War; in Alfred Frankenstein’s apt description, the musical portions weave disparate materials, including a waltz, tango, ragtime, march and gypsy melody, “into a fabric of stretched metres with constantly shifting accents and a highly dissonant harmony, attaining a bitter and sardonic quality” – neither the foundation nor the attitude of jazz.)

Gershwin clearly viewed himself not as a modernist but as a traditionalist. He firmly believed that “to express the richness of [American] life fully, a composer must employ melody, harmony and counterpoint as great composers of the past have employed them.” To that end, he asserted the need for knowledge of traditional techniques and loosely modeled his Concerto in F upon the three traditional movements of the genre – an opening sonata, an andante respite and a rondo finale.

Gershwin clearly viewed himself not as a modernist but as a traditionalist. He firmly believed that “to express the richness of [American] life fully, a composer must employ melody, harmony and counterpoint as great composers of the past have employed them.” To that end, he asserted the need for knowledge of traditional techniques and loosely modeled his Concerto in F upon the three traditional movements of the genre – an opening sonata, an andante respite and a rondo finale.

Gershwin described the first movement as “quick and pulsating,

THE FIRST MOVEMENT

The startling percusssion opening:

The "Charleston" motif:

The piano entrance with the lyrical theme:

|

reflecting the young, enthusiastic spirit of American life.” The opening is a knockout, boldly proclaiming the excitement that lies ahead – four tympani strokes, a cymbal clash, a bass drum thud and a snare drum roll in strict 4/4 rhythm, all repeated, leading directly to a “Charleston” motif, an arpeggiated figure in dotted rhythm and a serene but playful main theme. Thus, in a flood of invention, Gershwin startles us with novel sound, injects a wildly popular dance craze of the era, “swings” a traditional opening gambit with a “jazzy” rhythm, and lowers the emotional heat to sensitive contemplation – and that’s just the first few pages! Charles Burr salutes the opening as “certainly one of the most passionate and inspired pieces of composition in existence. It dominates the whole piece, and there is no other music that is quite like it.”

From there, things get far more subtle and sophisticated. As Steven Gilbert demonstrates, while the Rhapsody in Blue had been modeled on Broadway song structure, confining development to one melody at a time, here Gershwin indulges in “contrapuntal layering,” in which multiple melodic lines are developed simultaneously. (Benjamin Lee analogizes the appearance, expansion and return of Gershwin’s themes to an inventive variation upon the exposition, development and recapitulation of sonata form.) While most of Gilbert’s granular structural analysis goes way over my head, he clearly demonstrates the interrelationship of themes and a tightly-knit structure that trounces those who dismiss the work as poorly developed and a product of mere intuition rather than a carefully-worked out artistic plan (although, as with most composers of genius, it undoubtedly flowed from Gershwin more subconsciously than schematically). Yet, the wonder of Gershwin remains – while his “serious” output may bear scholarly scrutiny, and while the score is fully prescribed, it always sounds spontaneous and free. A further observation: Gershwin’s themes strike me as inherently symphonic in the sense that, unlike pop tunes, they are deliberately incomplete and demand elaboration to make much musical sense. Just consider the lyrical theme of the first movement, a motif more than a melody that cannot possibly satisfy on its own but rather is ripe for development. Yet it also carries to the extreme Gershwin’s penchant for repeated notes, syncopation and small intervals in his melodies, offset by his characteristic rapid harmonic changes (all of which form a compelling impression of jazz).

According to Gershwin, the second movement,

THE SECOND MOVEMENT

The langorous horn opening:

Piu mosso – the bluesy piano picks up the pace:

|

marked Andante

“has a poetic, nocturnal atmosphere which has come to be referred to as the American blues, but in a purer form than that in which they are usually treated.” (This comment further reflects Gershwin’s rather surprising disdain for what we now consider the authentic jazz and blues of his era, which he considered primitive sources waiting to ripen and be amalgamated into a genuine American music.) Lee adds that the Andante reflects the blues more in character than in structure, as it features half-step melodic inflection and four-bar phrases but without coalescing into the 12-bar AAB pattern of a traditional blues stanza. As an example of Gershwin’s eclecticism, Struble traces his melodic use of slowly tremulated major and minor thirds to Yiddish theatre and cantorial chants. Structurally, Gilbert calls it a song form turned rondo.

Speaking of blues, Gershwin faced a steep challenge from his chosen solo instrument, as the characteristic “blue notes” cannot be played directly on a keyboard having keys that produce only fixed tones. His solution was to sound adjacent notes together to approximate the intended effect of tones that “fall between the cracks” of the piano keys. In the second movement, he further specifies that the entire string section strum four-note chords to accompany the animated piu mosso section, as if to emulate banjos, a predominant rhythm instrument in period jazz bands.

The third and final movement, to Gershwin, “reverts to the style of the first.

THE THIRD MOVEMENT

Busy hands — allegro agitato:

... and some more "blue" notes:

|

It is an orgy of rhythm, starting violently and keeping the same pace throughout.” Marked allegro agitato, the piano role in repeatedly presenting the main theme is a bravura display, rapidly alternating the two hands in a show of frenzied motion that looks far harder to play than it really is but flatters the soloist into dazzling naive audiences. In Gilbert’s detailed analysis it’s a rondo, but a complex one, structured ABACCCDCAECABA, after which, in a gesture of formal unity, the theme of the opening movement returns as a coda, ending with final authoritative statements of the tympani fanfare and the Charleston motif with which the work began.

Yet, when all is said and done, structural details and analyses of this work seem somewhat beside the point. Rather than acceding to critical accusations of Gershwin's alleged technical flaws, inadequate study and limited talent, Struble urges that the Concerto in F needs to be heard holistically – it’s full of awkward, clumsy moments that shouldn’t work theoretically but somehow manage to pack a tremendous acoustical punch. He asserts that its orchestration, while unconventional, is perfectly suited to the inherent nature of the ideas and concludes that, despite technical shortcomings, the Concerto in F is one of the most striking and original pieces of the 20th century. I would add that it packs a terrific emotional wallop as well, constantly erupting with vigor and joy yet offset with lots of introspection, and all in a comfortable, modern context with which, nearly a century after the close of the “jazz age,” we can fully identify.

Gershwin’s writings suggest that his performance preferences were basically rather conservative, but with intensive rhythmic vitality. Thus, he envisioned his ideal ensemble as a combination of a highly-trained symphonic orchestra and a rhythmically-responsive swing band, in which rhythms should be “made to snap and crackle. … The more sharply the music is played, the more effective it sounds.” As he disdained the crudity of jazz and the tendency of its practitioners to exaggerate their expression, he further directed that “a conductor must rule the musicians’ fancy with an iron hand.”

Gershwin’s writings suggest that his performance preferences were basically rather conservative, but with intensive rhythmic vitality. Thus, he envisioned his ideal ensemble as a combination of a highly-trained symphonic orchestra and a rhythmically-responsive swing band, in which rhythms should be “made to snap and crackle. … The more sharply the music is played, the more effective it sounds.” As he disdained the crudity of jazz and the tendency of its practitioners to exaggerate their expression, he further directed that “a conductor must rule the musicians’ fancy with an iron hand.”

Gershwin left us two fragments of his own playing of the Concerto in F. The first must be written off as an anomaly. In 1934 he played the finale on the Rudy Vallee radio program, seemingly in an adaptation for the studio band, which mechanically plods through the score.  Beyond that, his solos are rough and thick, devoid of animation and replete with blurred phrasing, wrong notes and rhythmic insecurity. Everyone has an occasional off-night; perhaps this was one of Gershwin’s. Far more revealing is a well-worn disc of the last third of the andante (beginning with the piano solo following rehearsal number 9), this time on his own April 7, 1935 radio show and presumably with his own orchestra that builds to a thrilling climax. Here, the solos are trenchant but with pliant phrasing that follows rather closely the score (which, after all, is replete with detailed expression and tempo indications). Gershwin's orchestral ideals can be gleaned from our only example of him conducting – a 1931 NBC broadcast of his Second Rhapsody (in which he also was the pianist). The work itself is a rather disappointing quarter-hour of empty sequencing devoid of memorable melody. Even so, both the orchestral and solo parts are assertive and alive with more than enough rhythmic and dynamic accentuation to compensate for the vacuous content. Beyond that, his solos are rough and thick, devoid of animation and replete with blurred phrasing, wrong notes and rhythmic insecurity. Everyone has an occasional off-night; perhaps this was one of Gershwin’s. Far more revealing is a well-worn disc of the last third of the andante (beginning with the piano solo following rehearsal number 9), this time on his own April 7, 1935 radio show and presumably with his own orchestra that builds to a thrilling climax. Here, the solos are trenchant but with pliant phrasing that follows rather closely the score (which, after all, is replete with detailed expression and tempo indications). Gershwin's orchestral ideals can be gleaned from our only example of him conducting – a 1931 NBC broadcast of his Second Rhapsody (in which he also was the pianist). The work itself is a rather disappointing quarter-hour of empty sequencing devoid of memorable melody. Even so, both the orchestral and solo parts are assertive and alive with more than enough rhythmic and dynamic accentuation to compensate for the vacuous content.

Fortunately, Gershwin left us additional, if indirect, guidance toward his authentic “serious” style. Foremost among them is his June 10, 1924 acoustic recording of the Rhapsody in Blue, or at least as much of it as could fit on a double-sided 12-inch 78. Cut with the same Whiteman players who had given the premiere four months earlier, the pacing is brisk, the dynamics extreme, the inflection brash, and Gershwin’s solos biting, tense and driven, yet so free-flowing as to sound as though they were improvised on the spot, imbued with the very breath of creation. (Remarkably, in addition to a 1927 Gershwin/Whiteman electrical remake, we have a 1927 German Rhapsody in Blue by Mischa Spolinsky and the Julian Fuhs Orchestra that, whether through inspiration or mere imitation, adheres disarmingly close to the audacious spirit of the original and thus serves to confirm the prevalence and authority of its style.) Admittedly, the Concerto was intended to be more staid than the Rhapsody. Perhaps the best example of Gershwin's more "serious" style lies in two sets of tunes from his latest shows (four each from Tip Toes and Oh! Kay) that Gershwin recorded as fox trots in 1926. While adhering to the demands of a steady, moderate dance tempo, he infuses every phrase with fabulously vital rhythmic accents and an overall joie de vivre. (An added bonus is bypassing the lyrics which, while undoubtedly successful at delighting elite humor of the times, seem more cloying than clever nowadays – consider: “Won’t you do, do, do what you done, done, done before, baby?”) Yet a further suggestion of Gershwin's free-wheeling style lies in the 1932 publication of his Songbook, comprising sheet music for 18 of his songs, each provided both both for voice with straightforward accompaniment plus in a transcription for piano alone, the latter mostly in the form of highly elaborate, captivating variations.

The history of Concerto in F recordings is quite atypical. Unlike nearly every other piece I’ve considered on this website, its earliest recordings, while historically important, seem far less significant in terms of sheer performance quality.

The history of Concerto in F recordings is quite atypical. Unlike nearly every other piece I’ve considered on this website, its earliest recordings, while historically important, seem far less significant in terms of sheer performance quality.

- Roy Bargy and the Paul Whiteman Orchestra (1928, Columbia 78s, Sony Masterworks Heritage CD; 23:50)

Only one recording of the Concerto in F was released during Gershwin’s short lifetime.  Whiteman apparently was miffed that, after having commissioned and popularized the Rhapsody in Blue and thereby launched Gershwin’s career as a serious composer, Gershwin had bypassed him for the first concert presentation of his first full classical work. Nonetheless, Whiteman seized the opportunity to cut the first recording, but in an arrangement by Ferde Grofé. To deepen the insult, in lieu of the obvious choice for the soloist – Gershwin himself – Whiteman used the staff pianist in his band. Historical significance aside, the sonics are thick, the performance prosaic and the arrangement perverse. Rumor has it that Whiteman walked out of the session, to be taken over by William Daly, a close associate whom Gershwin trusted with conducting a half-dozen of his shows, so the swift and steady pacing should be considered as exemplifying the composer’s preferred style. Remarkably, Daly takes the opening and closing sections of the Andante at a vastly faster clip than any subsequent reading, which lends it a far more diffident tone than the usual soulful reverie. Beyond Grofé’s several major cuts, the deeper problem lies in the arrangement, which is not merely different for the sake of being different but denies the essence of Gershwin’s original orchestration by replacing his varied and fully appropriate textures with a boring uniformity. Thus, from the very outset Grofé reassigns most string lines to the winds and brass, fills in syncopated silences with extraneous cymbal and brass phrases, and even tampers with the distinctive percussion introduction, substituting woodwind yelps and tremelo growls for the cymbal and snare drum parts. By hobbling its flowing structure, emaciating its bold sound and essentially turning the Concerto into a lame sequel to the Rhapsody in Blue, Whiteman’s message seems clear – if you won’t trust me with your new work, I’ll appropriate it anyway, and at the same time spoil your reputation by convincing the record-buying public that it’s just not all that good. (Message received – until recently the Gershwin estate barred further recordings of the Grofé version.) Whiteman apparently was miffed that, after having commissioned and popularized the Rhapsody in Blue and thereby launched Gershwin’s career as a serious composer, Gershwin had bypassed him for the first concert presentation of his first full classical work. Nonetheless, Whiteman seized the opportunity to cut the first recording, but in an arrangement by Ferde Grofé. To deepen the insult, in lieu of the obvious choice for the soloist – Gershwin himself – Whiteman used the staff pianist in his band. Historical significance aside, the sonics are thick, the performance prosaic and the arrangement perverse. Rumor has it that Whiteman walked out of the session, to be taken over by William Daly, a close associate whom Gershwin trusted with conducting a half-dozen of his shows, so the swift and steady pacing should be considered as exemplifying the composer’s preferred style. Remarkably, Daly takes the opening and closing sections of the Andante at a vastly faster clip than any subsequent reading, which lends it a far more diffident tone than the usual soulful reverie. Beyond Grofé’s several major cuts, the deeper problem lies in the arrangement, which is not merely different for the sake of being different but denies the essence of Gershwin’s original orchestration by replacing his varied and fully appropriate textures with a boring uniformity. Thus, from the very outset Grofé reassigns most string lines to the winds and brass, fills in syncopated silences with extraneous cymbal and brass phrases, and even tampers with the distinctive percussion introduction, substituting woodwind yelps and tremelo growls for the cymbal and snare drum parts. By hobbling its flowing structure, emaciating its bold sound and essentially turning the Concerto into a lame sequel to the Rhapsody in Blue, Whiteman’s message seems clear – if you won’t trust me with your new work, I’ll appropriate it anyway, and at the same time spoil your reputation by convincing the record-buying public that it’s just not all that good. (Message received – until recently the Gershwin estate barred further recordings of the Grofé version.)

That the primary disappointment of the premiere recording lay not in the performance but the arrangement is confirmed by a 2009 concert by Jean-Yves Thibaudet and the Baltimore Symphony Orchestra led by Marin Alsop (Decca CD; 31:30). Although sensitive, deeply committed and quite convincing, and while its patient pacing effectively emphasizes the classical aspect of the work, its sheer flavor still falls short of the full depth and invention of Gershwin’s variegated original. Incidentally, Whiteman himself left us an intriguing yet frustrating appendage to his role in the Concerto in F – an unpublished 1947 Hollywood Bowl concert, which collector Karl Miller was kind enough to share. Dazzling, dynamic and hugely dramatic, abetted by a brisk solo rendition from a young Earl Wild, it leaps right out of the starting gate and proceeds to an andante infused with inventive feeling that plunges without pause into a ferocious finale. Whiteman mostly reverts to the original score, with only slight “improvements” and wraps it all up in less than 28 minutes. Yet, before we can admire its vitality and impact, Whiteman shatters the mood with intrusions of a chorus, who pad the harmony with saccharine “ooh”s and lusty “aah”s that suggest a Hollywood caricature more than a legitimate sense of style. But for the ridiculous vocals, this would be a sensational souvenir and a heartening testament of a sinner’s redemption.

- Jesus Maria Sanroma, Boston Pops Orchestra, Arthur Fiedler (Victor 78s, 1940; 28:40)

- Earl Wild, Boston Pops Orchestra, Arthur Fiedler (RCA, 1961; 28:50)

Gershwin never wrote another large-scale instrumental work although, according to his sister Frances, before his untimely death (of a brain tumor at age 38) he felt he had only scratched the surface of what he planned to do, including a symphony and string quartets. Nor did he live to hear a recording of his authentic Concerto in F. That would come only in 1940, from Arthur Fiedler and the Boston Pops Orchestra, featuring the orchestra’s pianist, Jesus Sanroma, who was trained by Schnabel and Cortot in Paris but hailed from Puerto Rico and was known for his Latin temperament. In 1935 they had cut a fleet, impulsive, wonderfully spirited Rhapsody in Blue that Gershwin reportedly admired. They collaborated on other concerti – a bustling Mendelssohn First, a powerful Macdowell Second and even managed to inject a fair degree of vitality into the ponderous clichés of the Paderewski, but their Concerto in F is unexpectedly lackluster, with only occasional glimmers of the energy and impulsive phrasing of the composer’s own playing, barely offset by a first movement race to the finish, and compromised by dull sonics and some odd balances of piercing brass outbursts and barely audible tympani. In 1961 Fiedler and the Boston Pops remade the Concerto with Earl Wild and garnered well-earned critical accolades. Although billed on the album cover as “today’s leading Gershwin interpreter” (perhaps true at the time, if only by default), Wild had established a niche reputation for virtuoso transcriptions from Rameau and Bach to Wagner and Johann Strauss – and Gershwin. Here, he incites Fiedler, and together they apply vastly greater freedom to both solo and orchestral passages, augmenting the specific tempo indications of the score with vibrant expressive touches that magnify its spirit in a wholly apposite way. The package is further sparked by spectacular fidelity, complete with a window-rattling bass drum, as if to make amends for the deflated sound of the earlier Fiedler/Boston venture. before his untimely death (of a brain tumor at age 38) he felt he had only scratched the surface of what he planned to do, including a symphony and string quartets. Nor did he live to hear a recording of his authentic Concerto in F. That would come only in 1940, from Arthur Fiedler and the Boston Pops Orchestra, featuring the orchestra’s pianist, Jesus Sanroma, who was trained by Schnabel and Cortot in Paris but hailed from Puerto Rico and was known for his Latin temperament. In 1935 they had cut a fleet, impulsive, wonderfully spirited Rhapsody in Blue that Gershwin reportedly admired. They collaborated on other concerti – a bustling Mendelssohn First, a powerful Macdowell Second and even managed to inject a fair degree of vitality into the ponderous clichés of the Paderewski, but their Concerto in F is unexpectedly lackluster, with only occasional glimmers of the energy and impulsive phrasing of the composer’s own playing, barely offset by a first movement race to the finish, and compromised by dull sonics and some odd balances of piercing brass outbursts and barely audible tympani. In 1961 Fiedler and the Boston Pops remade the Concerto with Earl Wild and garnered well-earned critical accolades. Although billed on the album cover as “today’s leading Gershwin interpreter” (perhaps true at the time, if only by default), Wild had established a niche reputation for virtuoso transcriptions from Rameau and Bach to Wagner and Johann Strauss – and Gershwin. Here, he incites Fiedler, and together they apply vastly greater freedom to both solo and orchestral passages, augmenting the specific tempo indications of the score with vibrant expressive touches that magnify its spirit in a wholly apposite way. The package is further sparked by spectacular fidelity, complete with a window-rattling bass drum, as if to make amends for the deflated sound of the earlier Fiedler/Boston venture.

- Oscar Levant: (1) NBC Symphony Orchestra, Arturo Toscanini (RCA, 1942; 30:35), (2) New York Philharmonic, André Kostelanetz (Columbia, 1949, 31’)

Apparently as a patriotic gesture during the War, Toscanini broadcast the Concerto in F (along with other American works),  but he had no feeling for the native style. Curiously, in light of his reputation as a literalist, although he respects the score’s dynamic indications to a far greater degree than most others, he largely disregards the specified tempos, and gets things off to a forlorn start at a foursquare funereal pace. Rigid, impassive and literal throughout, even the languorous opening of the andante is metronomic and drained of all atmosphere. Even so, the Toscanini reading is instructive in a way, as it serves to prove that, despite his intentions, Gershwin did not fit comfortably into the mold of conventional serious music. Perhaps awed at the opportunity to work with the conductor deemed to be the world’s greatest at the time, Levant literally plays along, even though, as a close friend and acolyte of the composer, he clearly had some valuable ideas to contribute. Those are only slightly more evident in his 1949 studio recording with André Kostelanetz and the New York Philharmonic, in which he tends to enliven the solo passages, breaking away from orchestral sections nearly as impassive as Toscanini’s. An unpublished 1947 New York Philharmonic concert (also generously shared by Karl Miller) tends to confirm that Levant deferred to his conductors. Here, his work in each movement begins rather tentatively, consistent with stodgy orchestral openings, but then becomes far more expressive once Dmitri Mitropoulos leads the accompaniment into more vivid territory. While fundamentally serious, the overall aura is far more flexible than Toscanini allowed. Indeed, the evolution from staid to thrilling suggests the unique, spontaneous energy that concerts can generate when the performers allow themselves to be transported by the experience of live music, and especially here where the music is so inherently rousing. but he had no feeling for the native style. Curiously, in light of his reputation as a literalist, although he respects the score’s dynamic indications to a far greater degree than most others, he largely disregards the specified tempos, and gets things off to a forlorn start at a foursquare funereal pace. Rigid, impassive and literal throughout, even the languorous opening of the andante is metronomic and drained of all atmosphere. Even so, the Toscanini reading is instructive in a way, as it serves to prove that, despite his intentions, Gershwin did not fit comfortably into the mold of conventional serious music. Perhaps awed at the opportunity to work with the conductor deemed to be the world’s greatest at the time, Levant literally plays along, even though, as a close friend and acolyte of the composer, he clearly had some valuable ideas to contribute. Those are only slightly more evident in his 1949 studio recording with André Kostelanetz and the New York Philharmonic, in which he tends to enliven the solo passages, breaking away from orchestral sections nearly as impassive as Toscanini’s. An unpublished 1947 New York Philharmonic concert (also generously shared by Karl Miller) tends to confirm that Levant deferred to his conductors. Here, his work in each movement begins rather tentatively, consistent with stodgy orchestral openings, but then becomes far more expressive once Dmitri Mitropoulos leads the accompaniment into more vivid territory. While fundamentally serious, the overall aura is far more flexible than Toscanini allowed. Indeed, the evolution from staid to thrilling suggests the unique, spontaneous energy that concerts can generate when the performers allow themselves to be transported by the experience of live music, and especially here where the music is so inherently rousing.

Ironically, a better indication of Levant’s personality (as a musician, not as the whiny actor and self-proclaimed wit) emerged in two Gershwin-themed movies in which he plays heavily abridged finales of the Concerto in F. In the 1945 biopic Rhapsody in Blue (with Damrosch, who led the premiere, conducting) following the momentous gong clash there is a dramatic interruption to announce the composer’s death. In the 1951 American in Paris he fantasizes a concert in which he not only plays the solos but appears as conductor and multiple instrumentalists. Both are fleet and far more captivating than his full-length recordings. An additional bonus in the latter is the sustained shots of him at the keyboard that serve to emphasize the degree to which the piano remains active, even when barely heard above the full orchestra. That, in turn evokes the comment by Charles Burr that the piano “was Gershwin’s instrument and he played it like he’d invented it. The piano holds the [Concerto in F] together, it has such presence and authority, and more so in this music than in any other Gershwin we hear, through the piano, the composer’s own great, driving energy.”

- Morton Gould and His Orchestra (RCA LP, 1956; 31:25)

- Alec Templeton, Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra, Thor Johnson (Remington LP, 1954; 31:10)

I’ve grouped these together, as they present high expectations but disappointing results.   Like Gershwin, Morton Gould composed serious music from a Broadway background, but his recording, while faithful to the score, is rather dull, with an especially deadpan middle movement. More intriguing is Alec Templeton, a radio star, blind from birth, known for his improvisations and for popularizing (or perhaps defiling) the classics (as in “Bach Goes to Town” and “Scarlatti Stoops to Conga”), who adds several grace notes to the first piano entrance, but after teasing us with that promise of personalizing touches, then settles down to a wholly routine rendition. Even so, despite deliberate pacing, Johnson pays special attention to inner voices, so as to amplify the richness of Gershwin’s orchestration. Like Gershwin, Morton Gould composed serious music from a Broadway background, but his recording, while faithful to the score, is rather dull, with an especially deadpan middle movement. More intriguing is Alec Templeton, a radio star, blind from birth, known for his improvisations and for popularizing (or perhaps defiling) the classics (as in “Bach Goes to Town” and “Scarlatti Stoops to Conga”), who adds several grace notes to the first piano entrance, but after teasing us with that promise of personalizing touches, then settles down to a wholly routine rendition. Even so, despite deliberate pacing, Johnson pays special attention to inner voices, so as to amplify the richness of Gershwin’s orchestration.

- André Previn: (1) André Kostelanetz and his Orchestra (Columbia LP, Odyssey CD, 1960; 31:45) (2) Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra, André Previn (Philips CD, 1985; 32’); (3) London Symphony Orchestra, André Previn (EMI LP and CD, 1998; 32’)

Previn, too, had a versatile and prolific career ranging from serious composing and performance to dozens of highly credible jazz albums, including a set of fantasias on Gershwin songs in which he takes substantial rhythmic and melodic liberties and displays a fine feeling for the composer’s resourceful style. He also earns the distinction of having recorded the Concerto in F three times. All are fairly similar in concept and provide a fine balance of inflected solo freedom and more conventional ensemble passages.   For his first venture, Kostelanetz offers a far more incisive and empathetic accompaniment than he had provided for Levant, and the recording is quite detailed, affording a fine opportunity to appreciate and enjoy the felicities of Gershwin’s inventive scoring – a lovely reading, even if both artists seem just a bit reticent at times, especially in the Andante. (As an interesting – and perhaps significant – aside, Columbia issued both this and the prior Levant/Kostelanetz LP in its “CL” series for pop albums, rather than its “ML” classical designation.) After taking over the baton for his two remakes, Previn crafts an overall impression of a richly romantic work, with exquisitely tender solo passages nestled within an orchestral plan that tends to underscore Gershwin’s fundamentally conservative intentions and his successful integration of potentially disparate pop and serious elements that ensures the work’s historical significance. This is especially evident in his Philips outing, even though it stirs things up a bit with a coarser playing, deeper inflection and some unusual features – inaudible slap-sticks and wood blocks, a consistently startlingly loud cymbal and some huge dynamic stings to mark transitions and conclusions. The later EMI remake has somewhat sharper accents, contrasted tempos and more careful balances, hewing a middle course between the approaches of the other two. For his first venture, Kostelanetz offers a far more incisive and empathetic accompaniment than he had provided for Levant, and the recording is quite detailed, affording a fine opportunity to appreciate and enjoy the felicities of Gershwin’s inventive scoring – a lovely reading, even if both artists seem just a bit reticent at times, especially in the Andante. (As an interesting – and perhaps significant – aside, Columbia issued both this and the prior Levant/Kostelanetz LP in its “CL” series for pop albums, rather than its “ML” classical designation.) After taking over the baton for his two remakes, Previn crafts an overall impression of a richly romantic work, with exquisitely tender solo passages nestled within an orchestral plan that tends to underscore Gershwin’s fundamentally conservative intentions and his successful integration of potentially disparate pop and serious elements that ensures the work’s historical significance. This is especially evident in his Philips outing, even though it stirs things up a bit with a coarser playing, deeper inflection and some unusual features – inaudible slap-sticks and wood blocks, a consistently startlingly loud cymbal and some huge dynamic stings to mark transitions and conclusions. The later EMI remake has somewhat sharper accents, contrasted tempos and more careful balances, hewing a middle course between the approaches of the other two.

- Leonard Pennario, Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra, William Steinberg (Capitol, 1955; 29:40)

The mono era of Concerto in F recordings ended with two fine albums that were largely overlooked in the rush to stereo. Pennario and Steinberg choose finely-judged tempos, ideally poised between classical restraint and impetuous spirit, highlighted by reveling in the discontinuity among exaggerated tempos, brushing aside the score’s frequent qualification of “poco” (a little).   Details abound, such as having the cymbal strokes quickly rise in volume, rather than the sharp percussive impact that the "›" marks in the score suggest. Balances consistently favor the piano, even when it plays a supporting role beneath the orchestra. Yet, rather than be heard as a fluke, this serves to remind us of Gershwin’s ties to his primary instrument (and admire all the more his extraordinary achievement in scoring the Concerto so inventively for an augmented orchestra). Unfortunately, there seems to have been no CD reissue, so you may have to dust off your turntable to hear this. Details abound, such as having the cymbal strokes quickly rise in volume, rather than the sharp percussive impact that the "›" marks in the score suggest. Balances consistently favor the piano, even when it plays a supporting role beneath the orchestra. Yet, rather than be heard as a fluke, this serves to remind us of Gershwin’s ties to his primary instrument (and admire all the more his extraordinary achievement in scoring the Concerto so inventively for an augmented orchestra). Unfortunately, there seems to have been no CD reissue, so you may have to dust off your turntable to hear this.

- Julius Katchen, Mantovani and his Orchestra (Decca, 1955, 29:10)

One of the great joys of record collecting is not only being able to compare the nuances of up to dozens of renditions of a favorite work, but the sudden thrill of chancing upon a version that completely thwarts expectations. I bought this out of sheer perverse curiosity and in anticipation of hating how the signature sound of Mantovani’s luxuriant, cascading violins surely would ruin Gershwin’s brash, youthful essence, and I even planned to cite it as a dreadful mismatch of artist and repertoire. Instead, to me at least, this is the one of the finest recordings the Concerto in F has ever received. While perhaps far from idiomatic (whatever that might mean in a work like this), it exudes an intangible and ever-fresh sense of intrepid adventure and sheer joy that captures the Concerto’s unique place in music history. As if to set a mood of exploration, the first movement gets things off to a bizarre start with overly-long pauses, added trills and wildly disparate giddy and leisurely tempos, all of which disrupt the continuity and pave the way to extreme expressive flexibility once the piano takes over. The opening of the second movement, too, defies convention with an overtly “jazzy” trumpet that swoops into its phrases. Quick, eccentric and enthralling, while not a first choice for getting acquainted, Katchen and Mantovani craft a sense of sheer visceral excitement, invention and discovery that (to me) fully captures the revolutionary zeal of this impassioned work. And, yes, even those lush strings help to convey the serious aspirations of a work that truly straddles tradition and novelty. (The magic of the Katchen-Mantovani combination is accentuated by an RAI Symphony concert led by Arthur Rodzinski (Allegro CD, 33’) in which Katchen constantly chafes to animate a dour and overly cautious orchestral contribution.)

- Wayne Marshall, Aalborg Symfoniorkester (Virgin, 1995; 33’)

I hope this doesn’t sound racist, but given its jazz roots – as well as jazz’s own roots in Afro-American culture – I’ve always wondered how the Concerto would sound in the hands of Afro-American musicians.  Marshall provides an intriguing but partial answer – he was born in England and confines his career mostly to Europe, so the “-American” part remains open. His repertoire on the piano, organ and podium is eclectic, ranging from Handel to Duke Ellington, and an album of piano improvisations on Gershwin songs is inventive, thoughtful, playful and stylish. He brings those same qualities to the Concerto in F, in which he conducts a Danish orchestra in a hugely heartfelt and expressive rendition. Pacing varies considerably from the score’s specifications, launching with a frenzied opening and lapsing into hugely reflective piano solos. Abrupt transitions between disparate sections, each taken at extreme tempos, tend to impede the sense of an integrated, smoothly-flowing logical conception. “Jazz” elements emerge mostly in the Andante, in which instruments slide into their notes, occasionally with added “blue notes” and embellishments, and an unabashedly fat, gutteral, vibrato-laden trumpet that sounds far more immediate than the distant, evocative felt-crowned sonority specified in the score. At the risk of “breaking the line” – a cardinal sin of conducting in earlier eras – Marshall nearly suspends time altogether with breathtakingly delicate piano cadenzas and inflated grand pauses. As in live jazz, precision of execution is occasionally sacrificed for expression and spontaneity. The solos, in particular, breathe with a conversational ease. While not an interpretation suitable for a first acquintance with the Concerto in F, it’s a fascinating alternative to standard renditions – and surely in the spirit of the “jazz age” in which it was conceived. Marshall provides an intriguing but partial answer – he was born in England and confines his career mostly to Europe, so the “-American” part remains open. His repertoire on the piano, organ and podium is eclectic, ranging from Handel to Duke Ellington, and an album of piano improvisations on Gershwin songs is inventive, thoughtful, playful and stylish. He brings those same qualities to the Concerto in F, in which he conducts a Danish orchestra in a hugely heartfelt and expressive rendition. Pacing varies considerably from the score’s specifications, launching with a frenzied opening and lapsing into hugely reflective piano solos. Abrupt transitions between disparate sections, each taken at extreme tempos, tend to impede the sense of an integrated, smoothly-flowing logical conception. “Jazz” elements emerge mostly in the Andante, in which instruments slide into their notes, occasionally with added “blue notes” and embellishments, and an unabashedly fat, gutteral, vibrato-laden trumpet that sounds far more immediate than the distant, evocative felt-crowned sonority specified in the score. At the risk of “breaking the line” – a cardinal sin of conducting in earlier eras – Marshall nearly suspends time altogether with breathtakingly delicate piano cadenzas and inflated grand pauses. As in live jazz, precision of execution is occasionally sacrificed for expression and spontaneity. The solos, in particular, breathe with a conversational ease. While not an interpretation suitable for a first acquintance with the Concerto in F, it’s a fascinating alternative to standard renditions – and surely in the spirit of the “jazz age” in which it was conceived.

Although largely forgotten, the fine African-American conductor Dean Dixon (1915 – 1976) was born and raised in New York City’s Harlem but had to form his own orchestras and eventually emigrated to Europe after being denied all but a few token opportunities in America. While other of his recordings tend to be dynamic and bouncy, his contribution to a Hamburg Radio Symphony concert of the Concerto in F is rather prosaic, especially in the outer movements that are taken too slowly to make much impact, perhaps out of deference to his soloist, Radu Lupu, whose marvelously nuanced, deeply poetic approach Dixon may have felt compelled to complement. Another Hamburg Gershwin recording, although not of the Concerto, led by an African-American is a 1960 Rhapsody in Blue released on a Forum LP, with pianist Joyce Hatto in pre-scandal times and the Hamburg Pro Musica led by North Carolinian George Byrd (1926 – 2010), whose career also centered on Europe. Alas, while basically competent, it, too, is disappointingly bland, with few incidental touches that we might consider reflective of Byrd’s cultural roots, much less inspired or even mildly improvisatory.

- Katia and Marielle Labèque (two-piano version) (Philips, 1980; 31:30)

Among the obstacles Gershwin faced were rumors that he had not orchestrated the Concerto, or that he at least had plenty of unacknowledged help.  Feeding that suspicion was the striking sophistication of the orchestration, an astounding feat for a first effort at such a demanding task. Indeed, Gershwin exploits with remarkable creativity and skill the full resources of a large orchestra (2 flutes, piccolo, 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones and tuba, plus the usual strings and a battery of percussion). As Struble notes, as a consequence of his earlier career, which demanded an ability to transpose to any key to accommodate amateur singers and to play convincing versions of songs at sight, Gershwin was “chained to the piano” and his “thinking and instincts were inescapably pianistic.” Indeed, David Hogarth notes that Gershwin sketched the Concerto on four staves, as if written for two pianos. Yet, Gershwin asserted that he had delegated orchestration of the Rhapsody to Frede Grofé only due to Grofé’s intimate knowledge of the unique abilities of the members of the Whiteman orchestra for which it had been written, and even then that the piano score he gave to Grofé had contained extensive indications of orchestral colors. Gershwin further claimed that after receiving Damrosch’s commission he had bought Cecil Forsythe’s 1914 comprehensive manual on orchestration for the very reason that he wanted to orchestrate the Concerto himself. In that light, one of the most interesting versions of the Concerto is a two-piano score, which Gershwin prepared for a December 1926 concert from his original sketch. Hogarth considers this version to preserve the immediacy of Gershwin’s inspiration. Heard in a swift, enthusiastic, technically assured recording by the French Labèque sisters, one piano adheres to the original solo part while the other is assigned as much of the orchestral portion as her fingers can cover. Despite its excellence, it does present a problem – the very essence of the piano concerto genre is to contrast the sonority of the essentially percussive solo instrument against the variegated textures of the instruments of the orchestra, a distinction that is completely lost in a piano reduction (although stereo separation does help somewhat to differentiate the roles of the two pianos). Even so, it helps to focus attention on the splendor of the piece itself, as well as (albeit through its absence) the brilliance of Gershwin’s often overlooked ability as an orchestrator. Feeding that suspicion was the striking sophistication of the orchestration, an astounding feat for a first effort at such a demanding task. Indeed, Gershwin exploits with remarkable creativity and skill the full resources of a large orchestra (2 flutes, piccolo, 2 oboes, English horn, 2 clarinets, bass clarinet, 2 bassoons, 4 horns, 3 trumpets, 3 trombones and tuba, plus the usual strings and a battery of percussion). As Struble notes, as a consequence of his earlier career, which demanded an ability to transpose to any key to accommodate amateur singers and to play convincing versions of songs at sight, Gershwin was “chained to the piano” and his “thinking and instincts were inescapably pianistic.” Indeed, David Hogarth notes that Gershwin sketched the Concerto on four staves, as if written for two pianos. Yet, Gershwin asserted that he had delegated orchestration of the Rhapsody to Frede Grofé only due to Grofé’s intimate knowledge of the unique abilities of the members of the Whiteman orchestra for which it had been written, and even then that the piano score he gave to Grofé had contained extensive indications of orchestral colors. Gershwin further claimed that after receiving Damrosch’s commission he had bought Cecil Forsythe’s 1914 comprehensive manual on orchestration for the very reason that he wanted to orchestrate the Concerto himself. In that light, one of the most interesting versions of the Concerto is a two-piano score, which Gershwin prepared for a December 1926 concert from his original sketch. Hogarth considers this version to preserve the immediacy of Gershwin’s inspiration. Heard in a swift, enthusiastic, technically assured recording by the French Labèque sisters, one piano adheres to the original solo part while the other is assigned as much of the orchestral portion as her fingers can cover. Despite its excellence, it does present a problem – the very essence of the piano concerto genre is to contrast the sonority of the essentially percussive solo instrument against the variegated textures of the instruments of the orchestra, a distinction that is completely lost in a piano reduction (although stereo separation does help somewhat to differentiate the roles of the two pianos). Even so, it helps to focus attention on the splendor of the piece itself, as well as (albeit through its absence) the brilliance of Gershwin’s often overlooked ability as an orchestrator.

- Others, Disappointments and Regrets

Among the other recordings I’ve heard (and I do have my limits) I can recommend:

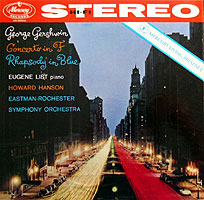

- Eugene List, Eastman-Rochester Symphony Orchestra, Howard Hanson (1957, Mercury)

- Jeffrey Siegel, St. Louis Symphony Orchestra, Leonard Slatkin (1974, Vox)

- William Tritt, Cincinatti Pops Orchestra, Erich Kunzel (1985, Telarc) )

- Peter Jablonski, Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, Vladimir Ashkenazy (1991, London)

- Garrick Ohlsson, San Francisco Symphony, Michael Tilson-Thomas (2004, RCA)

- Orion Weiss, Buffalo Philharmonic, JoAnn Falletta (2010, Naxos)

- Freddy Kempf, Bergen Philharmonic, Andrew Litton (2012, Bis)

All are well-played, enjoyable and boast special touches but, except for the 1957 List/Hanson, weigh in at over 32 minutes and strike me as too slow to convey the score's sheer inherent excitement.

My only severe disappointment is the 1993 concert recording by Sviatoslav Richter and the Stuttgart Radio Symphony Orchestra led by Christoph Eschenbach (Hansler; 36:30). While Richter fans salute this as evidence of the aging Russian master’s eclecticism, it’s not only painfully slow but incurably bland and constipated, with not even a hint of feeling for the idiom, complete with an Andante climax that sounds more like Bruckner than Gershwin. A very close, but slightly more stylish, second is the 1992 Arabesque CD by David Golub with Mitch Miller (!) conducting the London Symphony Orchestra, that lumbers in at nearly 36 minutes and whose high acclaim utterly eludes me. is the 1993 concert recording by Sviatoslav Richter and the Stuttgart Radio Symphony Orchestra led by Christoph Eschenbach (Hansler; 36:30). While Richter fans salute this as evidence of the aging Russian master’s eclecticism, it’s not only painfully slow but incurably bland and constipated, with not even a hint of feeling for the idiom, complete with an Andante climax that sounds more like Bruckner than Gershwin. A very close, but slightly more stylish, second is the 1992 Arabesque CD by David Golub with Mitch Miller (!) conducting the London Symphony Orchestra, that lumbers in at nearly 36 minutes and whose high acclaim utterly eludes me.

Regrets? If only the composer had left us a complete reading, if not conducted by himself then perhaps by Daly or another trusted colleague. It's also a shame that Leonard Bernstein never recorded the Concerto in F; judging from his slightly cut but deeply personal 1959 Columbia Rhapsody in Blue (not his flatter 1983 Los Angeles remake on DG), it might have been truly exceptional. Finally, I feel compelled to conclude this brief survey by offering my standard advance apology for overlooking readers’ favorite recordings, among which might lurk other fine or even revelatory discoveries.

I’ll take the credit (and blame) for my musical evaluations, but for the factual information, as well as the citations and quotes, I’m indebted to the following sources:

I’ll take the credit (and blame) for my musical evaluations, but for the factual information, as well as the citations and quotes, I’m indebted to the following sources:

|