|

The string quartets of Joseph Haydn afford a unique opportunity  in the annals of Western art – to trace the development of a major genre from birth to maturity, and all within the output of a single artist. A corollary benefit is to outline the evolution of a leading composer's genius, since Haydn's quartets extend from his very first to his very last published works. in the annals of Western art – to trace the development of a major genre from birth to maturity, and all within the output of a single artist. A corollary benefit is to outline the evolution of a leading composer's genius, since Haydn's quartets extend from his very first to his very last published works.

Just what is a quartet? The standard dictionary definition is merely a work written in four separate vocal or instrumental parts. But the string quartet, using an array of two violins, one viola and one cello, demands far more. Perhaps Goethe said it best: "a stimulating conversation between four intelligent people." The challenges and opportunities that the form presented to Haydn are summed up by Reginald Barrett-Ayres: "The limitations imposed by four stringed instruments appealed so much to his sensitive mind that he often used the string quartet as a means of expressing his deepest and innermost thoughts." To Henry Lang, Haydn poured into the medium his "love of life, inexhaustible humor and impeccable craftsmanship" and to Barrett-Ayres Haydn was "master yet student, scholar yet romantic, the essence of stability yet an adventurer." To Paul Griffiths, Haydn applied his abundant wit to the process of discovery of the essence of the quartet as a celebration of the arrival of language, just as a child claims a command of language by indulging in wordplay.

Just what is a quartet? The standard dictionary definition is merely a work written in four separate vocal or instrumental parts. But the string quartet, using an array of two violins, one viola and one cello, demands far more. Perhaps Goethe said it best: "a stimulating conversation between four intelligent people." The challenges and opportunities that the form presented to Haydn are summed up by Reginald Barrett-Ayres: "The limitations imposed by four stringed instruments appealed so much to his sensitive mind that he often used the string quartet as a means of expressing his deepest and innermost thoughts." To Henry Lang, Haydn poured into the medium his "love of life, inexhaustible humor and impeccable craftsmanship" and to Barrett-Ayres Haydn was "master yet student, scholar yet romantic, the essence of stability yet an adventurer." To Paul Griffiths, Haydn applied his abundant wit to the process of discovery of the essence of the quartet as a celebration of the arrival of language, just as a child claims a command of language by indulging in wordplay.

Griffiths likens the quartet to a living species and asserts that to search for its origins "is as vain as to search for the origins of man." Thus, it is hardly surprising that scholars trace the genesis of the quartet to many disparate roots.  Griffiths notes that works for four voices extend back to Pérotin in the late 12th century. Others cite a number of isolated examples of instrumental works specifying two violins, a viola and a cello by Gregori Allegri (1582 - 1662), Franz Xavier Richter (1709-89) and others, all of which predate Haydn. Barrett-Ayres finds Haydn's work – melding technique and feeling, form and freedom, rules and imagination – to be a synthesis of the extremes of two immediate predecessors – Georg Matthies Monn (1717-50), a master of technique but austere and cold, and Frantisck Xavier Dussek (1731-99), amateurish but full of feeling. Griffiths notes that works for four voices extend back to Pérotin in the late 12th century. Others cite a number of isolated examples of instrumental works specifying two violins, a viola and a cello by Gregori Allegri (1582 - 1662), Franz Xavier Richter (1709-89) and others, all of which predate Haydn. Barrett-Ayres finds Haydn's work – melding technique and feeling, form and freedom, rules and imagination – to be a synthesis of the extremes of two immediate predecessors – Georg Matthies Monn (1717-50), a master of technique but austere and cold, and Frantisck Xavier Dussek (1731-99), amateurish but full of feeling.

Most theorists trace the string quartet as having evolved from the Baroque trio sonata, which consisted of two melodic upper lines and a continuo of varying instrumentation comprised of virtually any lower voices (most often a harpsichord, but also organs, cellos, lutes or bassoons) to provide the harmonic base. Aside from the general impulsion of progress, the impetus for this development has been traced to the use of larger venues (and even the outdoors) where the continuo (especially a delicate harpsichord) would be sonically lost, a desire for structurally intricate music to stimulate musicians' interest, and the emergence of the viola as a viable instrument rising above its accustomed role as a mere adjunct to the cello and part of the continuo. Rosemary Hughes notes the esthetic logic of the result, as it parallels the constitution of the string section – divided violins, violas and cellos reinforced by double basses – that forms the foundation of the standard orchestra. Yet, she notes that until Haydn even music designated for four players was not cohesive, but rather tended to be showy and ornate.

How many quartets did Haydn write? The general consensus seems to be 69, although older authorities tend to cite 83. The higher figure credited quartet arrangements of a symphony and a sextet with two horns (Op. 1, #s 3 and 5), the seven-movement "Last Words of Christ on the Cross" and early works now thought to be spurious, while overlooking the so-called "Op. 0" that emerged relatively recently. Part of the confusion arose from Haydn himself, who included a set of six quartets published as his Opus 3 both in a reprint of his quartets in 1802 and in a catalog of his life work he prepared in 1805, although he had omitted them in an earlier listing of his output.  They now are thought to have been written by Romanus Hoffstetter, a monk who deeply admired Haydn and wrote: "everything that flows from Haydn's pen seems to me so beautiful and remains so deeply impressed in my memory that I cannot prevent myself now and again from imitating something as well as I can." (In the days before copyright, publishers often passed off amateur work as by famous compatriots.) Yet, some Haydn experts doubt that an amateur, no matter how devoted, could have produced work of such quality. Ironically, among the spurious works is the lovely serenade movement of Op. 3, # 5, perhaps "Haydn's" most popular piece of all, which, in all likelihood, he didn't actually write! They now are thought to have been written by Romanus Hoffstetter, a monk who deeply admired Haydn and wrote: "everything that flows from Haydn's pen seems to me so beautiful and remains so deeply impressed in my memory that I cannot prevent myself now and again from imitating something as well as I can." (In the days before copyright, publishers often passed off amateur work as by famous compatriots.) Yet, some Haydn experts doubt that an amateur, no matter how devoted, could have produced work of such quality. Ironically, among the spurious works is the lovely serenade movement of Op. 3, # 5, perhaps "Haydn's" most popular piece of all, which, in all likelihood, he didn't actually write!

(Were this a scholarly article – heaven forbid! – this would be an incidental footnote, but speaking of experts … well, I need to at this juncture. The following two sections may seem a pastiche of others' observations, but the fact is that in making my way through the mass of Haydn's massive and (to me) largely unfamiliar quartet output, I found my understanding vastly enhanced, far more than with more familiar music or more manageable chunks of the repertoire, by the guidance provided by several thoughtful analyses, and so it seems appropriate to summarize and pass them along for the benefit of readers rather than derive my own, far less useful, thoughts. The specific sources for these are given at the end of this article.)

In keeping with their general faith in progress, earlier critics tended to dismiss all but the last of Haydn's quartets. Thus, in the 1908 edition of Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians E. Heron-Allen wrote that "the early quartets of Haydn seem to us sadly feeble in the present day; there is not enough flesh to cover the skeleton; and the joints are terribly awkward." He asserted that only in the last 14 quartets, after "his long life of incessant practice" did Haydn "begin to show in the lower parts some of the boldness which had been only allowed to the 1st violin." Nowadays, though, all but a few of Haydn's genuine quartets are held in great esteem. In keeping with their general faith in progress, earlier critics tended to dismiss all but the last of Haydn's quartets. Thus, in the 1908 edition of Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians E. Heron-Allen wrote that "the early quartets of Haydn seem to us sadly feeble in the present day; there is not enough flesh to cover the skeleton; and the joints are terribly awkward." He asserted that only in the last 14 quartets, after "his long life of incessant practice" did Haydn "begin to show in the lower parts some of the boldness which had been only allowed to the 1st violin." Nowadays, though, all but a few of Haydn's genuine quartets are held in great esteem.

Consistent with the publishing custom of the time, nearly all of Haydn's quartets were released in sets of six, even though Haydn did not necessarily plan them as integral editions. Except for the unpublished "Op. 0," his first ten authentic quartets (together with two arrangements) were issued as his Opus 1 and 2. While their exact dates of creation are not certain, they are believed to have been written between 1752 and 1760, possibly in 1757 when a Baron von Fürnberg asked Haydn to compose a work for four string players (including Haydn) for a music-making party at his castle. Significantly, the compositions are labeled in his manuscripts as "notturni" and in his thematic catalog initially as "cassatio" and later as "divertimenti a quarto." Indeed, they bear a strong resemblance to the orchestral nocturnes, cassations and divertimentos of the time and Haydn clearly did not think of them as forging a new genre. Several modern commentators note that structurally they resemble suites, with the five traditional movements (allegro, minuet, adagio, another minuet, presto finale), all in major keys (except minuet trios), melodies characteristic of Austrian folksongs, much two-part harmony (often by doubling the two violins and viola/cello parts), imitative filler phrases of ascending and descending figures, and dominant violins whose occasional dialogues recall trio sonatas. Some have even posited that continuo parts should be inferred.

Joseph Haydn

1792 Portrait by Hardy |

While Hughes considers most movements clichéd, for her the minuets bloom with fresh melodies and imaginative tone color. In a delightful metaphor, Barrett-Ayers likens Haydn's first quartet outing to that of a "loose-limbed gangling colt … bounding hither and yon, trying out its legs, sniffing the air and loving all its sees and feels." Heard today, like Mozart's early symphonies they exude a touching, untroubled purity and sincerity; it's hard to disagree with Barrett-Ayers that "they contain some delightful music, simply expressed and molded with a subtlety and deftness which show Haydn to be a craftsman of the highest order, … a workman who took pride in everything he did … but something more – a truly gifted musician."

Haydn's next set of quartets, published as his Op. 9 came in 1770. In the interim decade he had entered the service of the royal Esterházy family and was installed in their castle, where he was expected to compose prolifically and produce appropriate music for their frequent entertainments. Haydn apparently recognized that his new set of quartets represented a quantum leap, as in his retirement he reportedly told his publisher Artaria to exclude all the predecessors from a planned collected set of his string quartet output. Griffiths and Geiringer attribute this mainly to a new emphasis upon dialogue among instruments – ideas are not merely imitated or repeated but modified and developed as they are passed from voice to voice, and sequencing and modulation evolve into elaboration, all of which were to become hallmarks of the maturity of the medium. Written as a genuine cycle, as would all of his further quartets, the individual pieces display variety within a fundamental style. Here, they feature a virtuostic first violin part, presumably written for Luigi Tomasini, an excellent violinist whom his deeply devoted patron had hired for the court orchestra, and interior 6-4 cadences suggest opportunities for Tomasini to improvise cadenzas. Despite the dominance of the violin, Barrett-Ayres notes that the primary difference from symphonies of the time was that the symphonies' repeated sequencing and variety of timbres satisfied listener demands while boring the executants, whereas quartets strove to present intrinsic interest for the players. Put another way, David Francis Tovey states that the self-sufficiency of each part marks the emergence of the quartet from the matrix of the orchestra. The result, as noted by István Barna, was a radical shift in purpose – these were consciously written to engage listeners' concentration, rather than serving as mere background for conversations of aristocratic company. From this point forward, all Haydn quartets would be shorn of the second dance movement, although in his next dozen (perhaps in keeping with their generally light tone, in which a rest seems appropriate to prepare for the vigorous finale) the minuets would precede the adagios.

In each of the next two years Haydn wrote six more quartets, published as his Opp. 17 and 20.

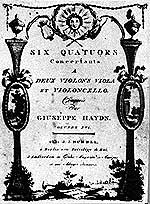

"Sun" Quartets - title page |

As many have noted, the figure of the sun on the title page of Op. 20 was fitting, as it boasted developments of vast significance to the genre and a symbolic birth of the true string quartet. Tovey considers Op. 20 among the most important documents in the history of music. Their many advances heralded by commentators include the emancipation of the cello and the emergence of its unique character, the achievement of parity of the four parts (enforced in part through the device of several fugal finales which, although a throwback to prior Baroque principles, emphasized equality of all instrumental lines), an awareness of the texture and tone quality of each instrument and the consequent emergence of its personality, an overall deepening of expression (perhaps most exemplified through increased use of the minor mode), the use of asymmetrical subjects to assert Haydn's personality, and form that emerges from intensive motivic development rather than being imposed by outward architecture. James Webster notes that Haydn's Opp. 9, 17 and 20 emerged during the "strum und drung" ("storm and stress") literary movement and shared the wider emotional range of Haydn's symphonies of the same period.

After this astounding outburst of discovery and excellence, Haydn wrote no further quartets for nine years. Hughes speculates that he may have succumbed to the demands of routine work for his Prince, or perhaps that his instinct demanded that he wait until he could reach a new plateau. Known as the "Russian Quartets," not because of Slavic influence over their content, but merely because they were first played at the home of the Russian Prince and future Czar, Haydn described his next Op. 33 cycle as written in "a completely new and special style," even though most scholars regard them more as a consolidation of his prior work than truly novel, Ludwig Finscher going so far as to regard the tag as misleading and a mere marketing gimmick. Yet their quality is universally praised. Thus, Marion Scott notes that the first notes of the first subject generate the melodic dimensions of an entire work, likening it to a seed that strikes roots, stems, leaves and flowers that grow until the plant is a mass of beauty. Geiringer, too, hails their thematic elaboration raised to the status of a main stylistic feature, and especially the dissecting and reassembling of fragments of the subject which, Webster notes, is developed in all the parts within a primarily homophonic structure. László Somfai salutes their concentration and restlessness that leaps beyond Haydn's classical ideals to anticipate 20th century chamber music. Barrett-Ayres cites their luminous, translucent texture and jubilant finales, which he attributes to the influence of Mozart's early quartets. Hughes credits them with effortless fluency, and Griffiths hears in them the first full pervasive flowering of Haydn's trademark wit, culminating in surprises such as the end of Op. 33 # 2 in broken phrases, 4˝ bars of silence and a final whimper. Perhaps for the last reason, they became hugely popular, appealing alike to connoisseurs and unsophisticated listeners, the demand generating dozens of transcriptions and four further editions in two years and stimulating others (including Mozart) to write quartets of their own. Somfai even credits the Op. 33 cycle with launching one of the first known professional string quartets, which toured them (and other works) for eight months in private homes and public concerts in a number of cities, thus spreading Haydn's growing celebrity yet further.

Haydn's Op. 33 quartets were highly influential, but perhaps their greatest impact was upon Mozart, who met Haydn in 1781 and performed with him. (Talk about superstar concerts!) As Geiringer notes, their personalities and temperaments were diametric opposites: Mozart, who developed and wrote quickly, was young, moody, a flamboyant solo performer and a disorganized spendthrift, while Haydn, 24 years older, was deliberate, calm, steadfast, private, precise and thrifty. Yet, they loved each other's work, Haydn famously proclaiming on a number of occasions that Mozart was the greatest composer of all, and Mozart reciprocating by asserting that it was only from Haydn that he learned to write quartets. (Indeed, scholars believe that Mozart may have been stimulated to write a set of six earlier quartets, K. 168-173, in response to Haydn's Opp. 9 and 17.) The young admirer then embarked on his own first set of mature quartets, and after two years of highly uncharacteristic struggle produced six (K. 387, 421, 428, 458, 464 and 465) which he felt worthy of being dedicated to Haydn. Griffiths notes that while Haydn's were carried forward by development, Mozart strove for balance and resolution, and of course they were suffused with his ineffable formal perfection and grace.

Somfai notes with some irony that the huge impact of the Op. 33 set and its many imitations upped the ante for Haydn's next quartets, which continued to consolidate his achievements in the genre. Thus, after another lengthy gap, during which he continued to pour out symphonies and a curious single quartet (Op. 42), his next six quartets (Op. 50 – 1787) focused on further unification by basing entire movements upon the components of a single theme, rather than contrasting ideas, and generally exploiting the resulting motifs to expand the development sections of sonata form movements. The next dozen, published as Opp. 54 and 55 (three each, 1788) and Op. 64 (six, 1790) are regarded as retrenchments in which the first violin resumes dominant brilliance, in part to gratify Johann Tost, a former Esterházy violinist who had become a wealthy merchant and who commissioned them. Incidentally, Op. 64 includes the thoroughly delightful "Lark" Quartet, which was the most popular of Haydn's "early" quartets and thus played a crucial role in apprising concert-goers and record buyers of the vast world that preceded the widely-acknowledged final masterpieces.

Haydn's next quartets, published in two sets of three as Opp. 71 and 74, reflect a drastic change in the composer's life. After his three decades of devoted service to the Esterházys his music-loving patron died, and the heir summarily dismissed the court musicians and relieved Haydn of his duties. Perhaps not enthused with the prospect of ending his life as a servant, Haydn turned down offers of new court appointments and instead accepted an opportune offer by Johann Peter Salomon, a German violinist turned English impresario, to come to London, where he was feted as artistic royalty. Written in 1795-6 upon his return to Vienna, the new sets of quartets were intended for a second London visit and reflect the freedom and cosmopolitan influences the former provincial servant had never known before. Of equal importance, they were aimed for public performance in vast concert halls before eager crowds rather than in the more intimate confines of a royal castle before invited dignitaries. This is immediately apparent from their opening notes – like his "London" symphonies, they begin with expectant hushed passages or bold introductory gestures, as if to briefly quiet a restive audience before settling down to business. Other elements to appeal to popular audiences noted by Webster include their more original themes, bolder contrasts and distant keys. But beyond specific ingredients, Barrett-Ayres considers their overall texture and instrumentation to reflect an orchestral quality, their character to herald a battle between Haydn's classical roots and emerging romantic tendencies and, perhaps most important, a shift of perspective from a primarily intimate performers' medium to one oriented toward ticket-buying listeners in a public venue. The radical reorientation paved the way to Haydn's final set of quartets, universally hailed as his masterpieces.

Commentators generally concur that Haydn's next and final set is the greatest among his many quartet masterworks – "the harvest" (Bennett-Ayres), "excelsior" (Geiringer) and "songs of experience" in which "Haydn's creative life reaches its fulfillment" (Hughes). Written in 1796 or 1797 (the autographs are lost and the chronology is somewhat speculative), they were commissioned by Count Joseph Erdödy who specified exclusive use for three years. When published in 1799 and dedicated to him (thus their occasional reference as the "Erdödy Quartets"), they first appeared in Vienna in two sets of three as Opp. 75 and 76, and then took their final form together in London as Op. 76. Back from England, financially independent and liberated from servility and prior routine, Haydn was at last free to write as he wished and poured himself into the new quartets (as well as his most ambitious and ultimately most popular work of all, the "Creation" oratorio). The result was an intensification of his prior achievements with added weight and character. The respected author and music historian Charles Burney hailed them as "full of invention, fire, good taste and new effects" and proclaimed that he "had never received more pleasure from instrumental music." Each of the six quartets displays this fine balance between consolidation of the tradition Haydn already had created and his irrepressible drive toward yet further innovation, and boasts sufficient riches to warrant individual consideration. Commentators generally concur that Haydn's next and final set is the greatest among his many quartet masterworks – "the harvest" (Bennett-Ayres), "excelsior" (Geiringer) and "songs of experience" in which "Haydn's creative life reaches its fulfillment" (Hughes). Written in 1796 or 1797 (the autographs are lost and the chronology is somewhat speculative), they were commissioned by Count Joseph Erdödy who specified exclusive use for three years. When published in 1799 and dedicated to him (thus their occasional reference as the "Erdödy Quartets"), they first appeared in Vienna in two sets of three as Opp. 75 and 76, and then took their final form together in London as Op. 76. Back from England, financially independent and liberated from servility and prior routine, Haydn was at last free to write as he wished and poured himself into the new quartets (as well as his most ambitious and ultimately most popular work of all, the "Creation" oratorio). The result was an intensification of his prior achievements with added weight and character. The respected author and music historian Charles Burney hailed them as "full of invention, fire, good taste and new effects" and proclaimed that he "had never received more pleasure from instrumental music." Each of the six quartets displays this fine balance between consolidation of the tradition Haydn already had created and his irrepressible drive toward yet further innovation, and boasts sufficient riches to warrant individual consideration.

The first quartet of the series, in G major The first quartet of the series, in G major

The opening of the first Op. 76 quartet (cello part) |

is an astounding harbinger of Haydn's one-time student and ultimate successor in the course of music, yet without sacrificing any of Haydn's own trademarks. In a remarkable anticipation of Beethoven's 1804 Eroica Symphony, it begins with three sharp chords (another audience rouser) that introduce a triadic theme given by the cello (as if to show the extent of its emergence from the shadows of continuo). (In fairness, the opening chords were not an innovation, but rather a conventional opening of Italian overtures at the time.) Beethoven looms even larger over the ensuing adagio sostenuto, whose slow progressions, syncopations and rich harmonizations could easily fit into one of Beethoven's late quartets, and the menuetto, whose rapid one-to-a-bar pacing forecasts the scherzo that Beethoven would hone to perfection. Yet, Haydn hardly suppressed his own personality – the jolly bustle of the first movement gets hung up on a suspended chord of b-flat-d-f-g# (which only "resolves" into a crestfallen b-flat-c#-e-flat-g), the first violin tries to reassert itself by silencing the others in the adagio (which Barrett-Ayres credits as a Haydn formalistic invention, combining the structure of a rondo's recurring opening section with the key progressions of a sonata movement), the trio lumbers along on a loping theme dear to Haydn's lusty peasant heart, and the finale totters between major and minor (a Haydn predilection) before concluding with a major affirmation.

The second Op. 76 quartet, in d minor, is known as the "Quinten" ("Fifths") for its distinctive opening motif of falling tonic and dominant open fifths which generate the entire work (and, perhaps not coincidentally, The second Op. 76 quartet, in d minor, is known as the "Quinten" ("Fifths") for its distinctive opening motif of falling tonic and dominant open fifths which generate the entire work (and, perhaps not coincidentally,

The "fifths" motif of the Quinten Quartet |

are the familiar sounds of Big Ben, whose pealing may have stuck in Haydn's ears in London). Barrett-Ayres calls this exemplar of monothematicism "the most superb treatment of concentrated thought in all of Haydn's quartets," as it weaves the entire fabric of the work. He also marvels at how Haydn compresses the recapitulation of the volatile, dynamic and intense sonata form first movement (40 measures v. the exposition's 56) to allow room for a lengthy coda. Throughout the respite of the andante o piů tosto ("rather like") allegretto the violin plays elaborations of a tune based on the opening motif's falling fifths above the others' accompaniment. The extraordinary third movement has been dubbed the "witches' minuet" for its rather grim tone and intentional lack of grace – Tovey called it "clowns dancing with flat feet" – but its most extraordinary feature is the sheer discipline of its rigid structure – a strict canon between violins followed at one bar by viola and cello, all in octaves – as Barrett-Ayers notes, an extraordinary result of Haydn's lifelong preoccupation with counterpoint, and yet a throwback to his habit of octave doubling in his earliest two-part work. Prior to a final plunge into D major, the vivace assai finale is a delirious peasant dance of furious gypsy fiddling spiced by drones, syncopations, dynamic accents and teasing pauses, which Geiringer relates to the music of Hungary, where Haydn had worked for thirty years.

The third quartet, in C major, is called the "Emperor." The third quartet, in C major, is called the "Emperor."

The Emperor hymn of the third quartet |

The "Gott Erhalte Franz Der [C]aiser" opening |

Apparently, Haydn was so impressed by "God Save the King" during his sojourns in England (and concerned over Napoleon's advance toward Vienna) that he wrote a hymn in honor of his own monarch, which ultimately became the Austrian national anthem ("Gott erhalte Franz der Kaiser" - "God Save the Emperor Franz"). The second movement is cast as the hymn and four variations in which, rather than being subject to development or elaboration, it is heard unvaried by each instrument in turn (second violin, cello, viola, first violin) to the others' varied accompaniment. Frankly, the theme is rather foursquare and static, its use seems more politically motivated than musically justified, and unless a listener's heart is swelled by nationalistic pride the movement proceeds as uncharacteristically dull. Yet, the presentation is sweet and gentle, thus mitigating much of the martial character on which Haydn otherwise might have capitalized. Perhaps to excite its intended audience with anticipation, Haydn builds the first movement from a theme that hints at the overall character of the hymn without directly emulating it, and, as a foretaste of the variations to come, exploits its potential through a wide variety of permutations. Yet Somfai goes further, noting that the opening theme of the first movement comprises G-E-F-D-C[K], representing the first letters of the hymn title, a musical symbol which, he asserts, audiences of the time would have immediately grasped. As many commentators have noted, the menuett is notable for its A major trio emerging from bittersweet a minor surroundings, as if in anticipation of another giant of the next generation, Schubert. Barrett-Ayers finds much of the finale to consist of monotonous padding, and somewhat disappointing in light of the bold character of its theme (alternating three bold tutti chords with a placid scalar motif), but redemption comes with an unexpected C major coda after dwelling throughout in the relative minor.

The fourth quartet, in B-flat major, is the "Sunrise," The fourth quartet, in B-flat major, is the "Sunrise,"

The "sunrise" theme of the fourth quartet |

aptly named for the exquisite theme that opens and shines throughout the first movement, rising caringly but surely in the violin over an expectant, sustained earth-bound tonic chord. The entire movement is magnificent, evolving organically from that wondrous opening that begs to be heard again and again and proves to be constantly fascinating in its growth, including a flurry of vigorous activity, an inversion that provides a mirror secondary theme in the celli, a temporary darkening of clouds in the development, and a final outburst shared with the other instruments. The whole process manages to sound fresh and spontaneous, yet unfolds with the utmost assurance, inevitability and formal observance – the sure sign, if one were really needed, of a master of both genius and humanity. Much of that same feeling animates the adagio, which Barrett-Ayers considers a fantasia, unfolding from an initial five-note motif derived from a fragment of the sunrise theme, as if Haydn, like us, couldn't get enough of it. The focal point of the minuet is its melancholy trio, whose pedals, hesitant syncopations and chromaticism H. C. Robbins Landon identifies as Balkan in feeling. On the other hand, Barrett-Ayres identifies the elegant but vigorous theme of the finale as English, perhaps in celebration of Haydn's success and happiness there, although a variation that plunges suddenly into the relative minor suggests something more Slavish. Just as its energy seems ready to slacken, Haydn quickens the pace with a figure that careens among the instruments, accelerates once more and wraps it all up in a final burst of unfettered energy.

In the last two Op. 76 quartets Haydn turns to structural exploration and an ample dose of mischievous humor. The opening movement of the fifth, in D major, departs from the sonata form of the first four to what Robin Golding can only describe as "unorthodox variations," as it really seems to defy conventional formal analysis and thwarts expectations, even while suggesting an intensely human struggle. Thus, its elegant, dignified dance theme in triple time devolves into d minor, fragments, repeats the first phrase in furious scalar runs, tries to reassert itself, but then breaks away and takes off at a faster clip propelled by sixteenth notes that never release their grip. Finally, the opening phrase keeps repeating itself until it gives up into a concluding cadence. The ensuing largo in the remote key of F# major provides another glance ahead to Beethoven with tender phrasing, soft dynamics and searching modulations. Haydn aptly labels it "Cantabile e mesto" – "singing and sad." Geiringer attributes its "tone quality of ethereal beauty" in part to the key, which precludes the use of open strings by any of the players. The minuet, too, contains unorthodox touches – each time it settles into its expected consistent triple time, syncopated duple figures disrupt the pace, and its trio, with constant activity never rising above a whisper, hints at deep secrets. The presto finale begins where it seemingly should end – with three insistent tonic cadences – and then gallops off in unbounded joy broken only by occasional grand pauses, its frantic pace, sustained length and jagged phrasing as challenging for the players to maintain as for listeners to marvel at. In the last two Op. 76 quartets Haydn turns to structural exploration and an ample dose of mischievous humor. The opening movement of the fifth, in D major, departs from the sonata form of the first four to what Robin Golding can only describe as "unorthodox variations," as it really seems to defy conventional formal analysis and thwarts expectations, even while suggesting an intensely human struggle. Thus, its elegant, dignified dance theme in triple time devolves into d minor, fragments, repeats the first phrase in furious scalar runs, tries to reassert itself, but then breaks away and takes off at a faster clip propelled by sixteenth notes that never release their grip. Finally, the opening phrase keeps repeating itself until it gives up into a concluding cadence. The ensuing largo in the remote key of F# major provides another glance ahead to Beethoven with tender phrasing, soft dynamics and searching modulations. Haydn aptly labels it "Cantabile e mesto" – "singing and sad." Geiringer attributes its "tone quality of ethereal beauty" in part to the key, which precludes the use of open strings by any of the players. The minuet, too, contains unorthodox touches – each time it settles into its expected consistent triple time, syncopated duple figures disrupt the pace, and its trio, with constant activity never rising above a whisper, hints at deep secrets. The presto finale begins where it seemingly should end – with three insistent tonic cadences – and then gallops off in unbounded joy broken only by occasional grand pauses, its frantic pace, sustained length and jagged phrasing as challenging for the players to maintain as for listeners to marvel at.

As with the fifth, the final Op. 76 quartet, As with the fifth, the final Op. 76 quartet,

The theme of the sixth quartet trio |

in E-flat major, begins with a seemingly leisurely sprawling melody that appears headed for a standard set of variations, but after the expected embellishments and injection of energy subside and it seems ready to wrap up, it snaps back to generate a fugue, which Haydn had used only once since his Op. 20 (and previously only in finales). As Donat points out, the combination of variations and a fugue would be enthusiastically taken up by Beethoven, Brahms and Reger. Next comes another Fantasia, this time focusing on extreme modulations from B to A-flat major. Indeed, the range is so extreme that for the first half Haydn doesn't even bother to specify a key signature, preferring instead to sprinkle the score with accidentals. Somfai calls it a "harmonic labyrinth." Donat notes that Haydn wrote the phrase "cum licentia" ("with freedom") on the parts, resorting to enharmonic notation mixing sharps and flats, so extreme are the modulations. Humor (and quite a bit of awe) returns in the trio (labeled "alternativo"), constructed almost entirely of repeated E-flat major scales and, eschewing the usual convention of the score signalling a repeat of the entire section, instead is written out at nearly twice the usual length. Vignal hails this section as "a feat of skill if ever there was one," as if Haydn was boasting, "See what I can do with just a scale." And as if that were not sufficient, the finale, too, is built largely upon short, rapid tonic scales, but this time with added rhythmic irregularity that often defies the sense of an expected recurrent downbeat. Barrett-Ayers notes that here Haydn leaps over Beethoven and his entire century to anticipate Stravinsky and Bartok, an altogether remarkable finish to an extraordinarily varied and daring set.

Although the six Op. 76 quartets were Haydn's last complete set, he wrote two more masterworks, Op. 77, and then tried to write another two in 1803 at the then extreme old age of 71 but was able to complete only the two inner movements, an adagio and minuet.

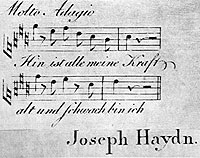

Haydn's calling card |

While Hughes cites their "chromatic fire and passion to testify that it was only the physical vitality that had burned itself out," Geiringer asserts that they show a certain lack of inventive power, and indeed one's perception is invariably tinged by the image of a depleted master no longer able to fully summon his formidable creative faculties. When issued in 1806 as Haydn's final, albeit incomplete, work the year before his death, the publisher reproduced Haydn's calling card with its poignant epigram from a favorite song, "Der Greis" ("The Old Man"): "Hin ist alle meine Kraft, alt und schwach bin ich." ("Gone is my strength, old and weak am I").

But despite all the scholarship, influence and devotion his quartets have attracted, perhaps Haydn had had his last say in an 1802 letter, cited by Geiringer, that he had written to admirers in Bergen, Germany, who had put together an amateur performance of his "Seasons" oratorio and who had conveyed their gratitude for his art:

Often, … when my powers both of body and mind were failing and I felt it a hard matter to persevere … a secret feeling within me whispered, "There are but few contented and happy men here below; everywhere grief and care prevail; perhaps your labors may one day be the source from which the weary and worn … may derive a few moments' rest and refreshment." What a powerful motive for pressing onward!

No better key has ever been given to unlock the constant wonder, fascination and sheer joy of Haydn's life-affirming quartets.

If any tangible measure of Haydn's success in revitalizing "the weary and worn" with "a few moments' rest and refreshment" be needed, surely it lies in the generally superb quality of recordings of his quartets. It's hard to go far wrong among them, perhaps because the very nature of the works inspires an extraordinary degree of enthusiasm, love and devotion among a wide swath of players. If any tangible measure of Haydn's success in revitalizing "the weary and worn" with "a few moments' rest and refreshment" be needed, surely it lies in the generally superb quality of recordings of his quartets. It's hard to go far wrong among them, perhaps because the very nature of the works inspires an extraordinary degree of enthusiasm, love and devotion among a wide swath of players.

At the outset, we should note that few performers of the Haydn quartets bother mentioning whether they use period instruments, and with good reason – it hardly matters, since even modern ensembles prize the fabulous string instruments made in Italy by Stradivari, Guarneri del Gesu, Amati and others generations before Haydn and aspire to play the surviving originals, as their gorgeous tone has never been matched, despite all the "progress" and "improvements" in instrument construction since then. Even modern craftsmen attempt to emulate them but have yet to uncover all their secrets. Yet while the instruments themselves haven't been altered since well before Haydn's time, techniques of playing them have changed considerably, as have stylistic approaches to older music. Among the fundamental issues to be determined by modern performers are tempos (in the days before metronome markings, scores merely specified abstract terms such as allegro, andante, etc.), whether to observe all repeats (and, if so, the degree to which they should be varied), ornamentation, dynamics and accents (most of which were omitted from scores, since performers were assumed to have the taste and training to know how and when to apply them), and which of the available editions to use (as many of the autographs have been lost, and Haydn's intent can be hard to glean beneath the gloss (and errors) added by generations of editors).

While scholars may have been aware of the scope and excellence of Haydn's achievements, in the public mind during most of the pre-LP era he had written a dozen or so great symphonies, two oratorios and not much else of value, and so it is hardly surprising that recordings of his quartets were few and far between. Isolated movements occasionally were used as filler to sets of other, presumably more important, quartets that required odd numbers of 78 rpm sides. The first ensemble to devote serious attention to Haydn was the Hungarian Léner Quartet (comprising Jenö Léner, Joszef Smilovits, Sándor Roth and Imre Hartmann), which recorded acoustical versions of Op. 76 # 5 and the spurious Op. 3 # 5 (probably for its famous serenade). Electrical remakes of both were joined by Op 64 # 5 (the "Lark") and Op. 76 # 3 (the "Emperor"), plus the andante of Op. 76 # 2. All were on Columbia 78s, and now Rockport CDs. Tully Potter describes their sound as "soupy" due to their extremely wide vibrato and he adds that their ensemble could be sloppy yet redeemed by a natural flair and warmth. Fascinating comparisons lie in the lighter, brilliant precision of a 1926 recording of Op. 76 # 1 by the Léner's compatriots, the Budapest Quartet, and the grace, rhythmic snap and considerably less portamento and vibrato in a 1928 set of the "Lark" by the Franco-Belgian Flonzaley Quartet, both of which sound comparatively modern. While the comparison suggests that the Léner may have sounded dated even at the time, their records (which, according to Gramophone, reportedly sold especially well in England and Japan) exemplify the somewhat indulgent romantic view of "Papa Haydn." in the public mind during most of the pre-LP era he had written a dozen or so great symphonies, two oratorios and not much else of value, and so it is hardly surprising that recordings of his quartets were few and far between. Isolated movements occasionally were used as filler to sets of other, presumably more important, quartets that required odd numbers of 78 rpm sides. The first ensemble to devote serious attention to Haydn was the Hungarian Léner Quartet (comprising Jenö Léner, Joszef Smilovits, Sándor Roth and Imre Hartmann), which recorded acoustical versions of Op. 76 # 5 and the spurious Op. 3 # 5 (probably for its famous serenade). Electrical remakes of both were joined by Op 64 # 5 (the "Lark") and Op. 76 # 3 (the "Emperor"), plus the andante of Op. 76 # 2. All were on Columbia 78s, and now Rockport CDs. Tully Potter describes their sound as "soupy" due to their extremely wide vibrato and he adds that their ensemble could be sloppy yet redeemed by a natural flair and warmth. Fascinating comparisons lie in the lighter, brilliant precision of a 1926 recording of Op. 76 # 1 by the Léner's compatriots, the Budapest Quartet, and the grace, rhythmic snap and considerably less portamento and vibrato in a 1928 set of the "Lark" by the Franco-Belgian Flonzaley Quartet, both of which sound comparatively modern. While the comparison suggests that the Léner may have sounded dated even at the time, their records (which, according to Gramophone, reportedly sold especially well in England and Japan) exemplify the somewhat indulgent romantic view of "Papa Haydn."

The sea change came in 1932 when the Belgian Pro Arte Quartet (Alphonse Onnou, Laurent Halleux, Germain Prevost, Robert Maas) launched a series of HMV sets of 78s, each with nearly an hour's worth of music on seven records containing three or four Haydn quartets (now available in the original configurations on Pristine Audio or combined into two Testament four-CD sets). As an indication of Haydn's lack of renown at the time and the consequent presumed financial risk, the project was undertaken by a Haydn Quartet Society, which sputtered after the fifth release in 1935, but by 1938 had issued eight volumes with 27 quartets (plus two of Hoffstetter's), but included only two of Op. 76 (the "Emperor" in 1934 and the "Sunrise" in 1938). In a 1937 review welcoming Volume 6, Gramophone offered its "highest praise," citing "the perfection of ensemble" and "continuous beauty of tone and finish." Notably, in light of Haydn's letter noted above, which assumed renewed significance on the eve of World War II, the review alluded to "the sanity of Haydn's music. It spells unbelievable peace to be able to leave this mad world, if only for a while, and recover in these inspired pages – the work of a man who had faith – a sense of proportion, a sense of certainty that all will be well, however dark the present outlook be." Heard today, the Pro Arte records amply reflect that view – a fine balance between level-headed focus and incisive commitment, with just enough grace and a hint of playfulness to rise above the mundane, and some deeply heartfelt phrasing (especially in the Emperor andante) – both a glance back at the romantic style of their predecessors and a salute to the devotion that the composer lavished on his work, while at the same time forcefully advocating the worth of these pieces for listeners of the future. (Alphonse Onnou, Laurent Halleux, Germain Prevost, Robert Maas) launched a series of HMV sets of 78s, each with nearly an hour's worth of music on seven records containing three or four Haydn quartets (now available in the original configurations on Pristine Audio or combined into two Testament four-CD sets). As an indication of Haydn's lack of renown at the time and the consequent presumed financial risk, the project was undertaken by a Haydn Quartet Society, which sputtered after the fifth release in 1935, but by 1938 had issued eight volumes with 27 quartets (plus two of Hoffstetter's), but included only two of Op. 76 (the "Emperor" in 1934 and the "Sunrise" in 1938). In a 1937 review welcoming Volume 6, Gramophone offered its "highest praise," citing "the perfection of ensemble" and "continuous beauty of tone and finish." Notably, in light of Haydn's letter noted above, which assumed renewed significance on the eve of World War II, the review alluded to "the sanity of Haydn's music. It spells unbelievable peace to be able to leave this mad world, if only for a while, and recover in these inspired pages – the work of a man who had faith – a sense of proportion, a sense of certainty that all will be well, however dark the present outlook be." Heard today, the Pro Arte records amply reflect that view – a fine balance between level-headed focus and incisive commitment, with just enough grace and a hint of playfulness to rise above the mundane, and some deeply heartfelt phrasing (especially in the Emperor andante) – both a glance back at the romantic style of their predecessors and a salute to the devotion that the composer lavished on his work, while at the same time forcefully advocating the worth of these pieces for listeners of the future.

Dozens of recordings of individual Haydn quartets were cut throughout the pre-stereo era.  While the vast majority of these are no longer available, record catalogs of the time list 78 sets by the Calvert, Capet, International, Poltronier, Prisca, Rich Queling, Roth and Wendling Quartets and LPs by the Amadeus, Baroque, Borchet, Budapest, Galimar, Griller, Hollywood, Hungarian, Italian, Koeckert and Vienna Kozerthaus Quartets, plus an extensive series by the Schneider Quartet (Alexander Schneider, Isador Cohen, Karen Tuttle, Hermann Busch) for the Haydn Society. Unfortunately, few are available nowadays to document the evolution and variety of styles of the era, but the Schneider series has been restored to currency on the Vinyl Fatigue website. Serious and weighty, their generally slow tempos yield affecting adagios, andantes and largos and respect the fundamental classical nature of the outer movements, but the minuets in particular tend to lack a vital spark and the sonic quality is rather flat. While the vast majority of these are no longer available, record catalogs of the time list 78 sets by the Calvert, Capet, International, Poltronier, Prisca, Rich Queling, Roth and Wendling Quartets and LPs by the Amadeus, Baroque, Borchet, Budapest, Galimar, Griller, Hollywood, Hungarian, Italian, Koeckert and Vienna Kozerthaus Quartets, plus an extensive series by the Schneider Quartet (Alexander Schneider, Isador Cohen, Karen Tuttle, Hermann Busch) for the Haydn Society. Unfortunately, few are available nowadays to document the evolution and variety of styles of the era, but the Schneider series has been restored to currency on the Vinyl Fatigue website. Serious and weighty, their generally slow tempos yield affecting adagios, andantes and largos and respect the fundamental classical nature of the outer movements, but the minuets in particular tend to lack a vital spark and the sonic quality is rather flat.

The stereo era saw an exciting development that heralded growning interest in the depth of Haydn's output – the production of integral sets of the entire quartet oeuvre.   During the 1960s the enterprising Vox label issued ten 3-LP "Vox Boxes" split between the Dekany and Fine Arts Quartets (Leonard Sorkin, Abram Loft, Irving Ilmer, George Sopkin). The latter's versions of the later quartets, including the Op. 76 set, boasts finely graded dynamics and tempo variation within a warm acoustic and a wide stereo soundstage that enables listeners to trace the individual instrumental lines, an important consideration where, as here, the players opt for a well-blended sonority. In the early 1970s they were joined by a second complete set by the British Aeolian Quartet (Emanuel Hurwitz, Raymond Keenlyside, Margaret Major, Derek Simpson), released in seven boxes of between three and six LPs on the Argo label in Europe and on London Stereo Treasury in America (and now combined in a budget Decca CD box). Like the Pro Arte, the Fine Arts projects a tangible sense of enthusiasm, sparked by inventive dynamics and added (and occasionally subtracted) grace notes, but always within a aura of elemental dignity that seems appropriate to the spirit of each work. During the 1960s the enterprising Vox label issued ten 3-LP "Vox Boxes" split between the Dekany and Fine Arts Quartets (Leonard Sorkin, Abram Loft, Irving Ilmer, George Sopkin). The latter's versions of the later quartets, including the Op. 76 set, boasts finely graded dynamics and tempo variation within a warm acoustic and a wide stereo soundstage that enables listeners to trace the individual instrumental lines, an important consideration where, as here, the players opt for a well-blended sonority. In the early 1970s they were joined by a second complete set by the British Aeolian Quartet (Emanuel Hurwitz, Raymond Keenlyside, Margaret Major, Derek Simpson), released in seven boxes of between three and six LPs on the Argo label in Europe and on London Stereo Treasury in America (and now combined in a budget Decca CD box). Like the Pro Arte, the Fine Arts projects a tangible sense of enthusiasm, sparked by inventive dynamics and added (and occasionally subtracted) grace notes, but always within a aura of elemental dignity that seems appropriate to the spirit of each work.

Although an integral set of the full run of Haydn quartets places the Op. 76 group in perspective (and provides an entire day's worth of mostly fine music), at least three are also available in more affordable and digestible segments, mostly comprising a single opus (or combining those having only three quartets) on two CDs. The complete Haydn quartet recordings of the Hungarian Tátrai Quartet (Vilmos Tátrai, István Várkonyi, György Konrád, Ede Banda) (3 LPs, 2 CDs, Hungaroton) have been universally praised since their series began with the Op. 76 set in 1964, and to many they still represent the epitome of achievement in this realm, managing a near-ideal blend of the range and qualities that make Op. 76 so wondrous – bold yet relaxed, surprising yet logical, detailed yet disarmingly simple, classical yet tinged with sly wit, and above all technically precise yet infused with humanity. No matter how many other renditions you’ve heard, you can always return to the Tatrai set for an intangible feeling of well-being and comfort that subtly compels awe of the magnitude and complexity of Haydn’s achievement and still speaks to us, utterly undimmed and immune from the abrasion and attenuation of all the time that has passed since its creation. at least three are also available in more affordable and digestible segments, mostly comprising a single opus (or combining those having only three quartets) on two CDs. The complete Haydn quartet recordings of the Hungarian Tátrai Quartet (Vilmos Tátrai, István Várkonyi, György Konrád, Ede Banda) (3 LPs, 2 CDs, Hungaroton) have been universally praised since their series began with the Op. 76 set in 1964, and to many they still represent the epitome of achievement in this realm, managing a near-ideal blend of the range and qualities that make Op. 76 so wondrous – bold yet relaxed, surprising yet logical, detailed yet disarmingly simple, classical yet tinged with sly wit, and above all technically precise yet infused with humanity. No matter how many other renditions you’ve heard, you can always return to the Tatrai set for an intangible feeling of well-being and comfort that subtly compels awe of the magnitude and complexity of Haydn’s achievement and still speaks to us, utterly undimmed and immune from the abrasion and attenuation of all the time that has passed since its creation.

A more recent set by the German Buchberger Quartet (Hubert Buchberger, Julia Greve, Jachim Etzekm Helmut Sohler) on Brilliant, has the added advantage of budget pricing.  Their readings are lively paced and sharply phrased, with incisive rhythm, crystalline recording, and a fresh, uninflected approach that seems entirely suitable in the earlier works but may strike some in Op. 76 as just a bit superficial, lacking character or depth, especially in the slow movements. Also economical and even more convenient are the more routine recordings of the Hungarian Kodaly Quartet (Atilla Falvay, Tamás Szabó, Gábor Fias, János Devich) on Naxos, all of which are available as single CDs (so that, for example, Op. 76 comprises one volume of #s 1-3 and another of #s 4-6). Both the Buchberger and Kodaly complete cycles are available in deeply discounted boxes, which make both storage and economic sense if you plan to get more than a few (although mixing and matching for the sake of variety makes sense as well). Their readings are lively paced and sharply phrased, with incisive rhythm, crystalline recording, and a fresh, uninflected approach that seems entirely suitable in the earlier works but may strike some in Op. 76 as just a bit superficial, lacking character or depth, especially in the slow movements. Also economical and even more convenient are the more routine recordings of the Hungarian Kodaly Quartet (Atilla Falvay, Tamás Szabó, Gábor Fias, János Devich) on Naxos, all of which are available as single CDs (so that, for example, Op. 76 comprises one volume of #s 1-3 and another of #s 4-6). Both the Buchberger and Kodaly complete cycles are available in deeply discounted boxes, which make both storage and economic sense if you plan to get more than a few (although mixing and matching for the sake of variety makes sense as well).

Also worth consideration are individual sets of Op. 76 by groups that have not ventured into the full series of Haydn quartets.

- Quatour Mosaďques

(Erich Höbarth, Andrea Bischof, Anita Mitterer, Christophe Coin) (naďve astree CD set, 2000) – Despite the French-sounding name, this is an offshoot of the Concentus Musicus Wien, and despite the lean, wiry sound of that esteemed ensemble’s pioneering recordings of Baroque repertoire, the Mosaďques nestle the Haydn quartets in rich warmth, abetted by a resonant acoustic, in which the cello is given unusual emphasis to challenge the violin’s natural dominance and to impart a symphonic texture throughout.   Thus, the cello’s anchor to the three chords that open Op. 76 # 1 linger to underline and thus integrate the opening theme, the canon of the # 2 trio is uncommonly spooky and the energy of the finale of # 5 is especially exhausting. Yet, more than in any other set I’ve heard, the Mosaďques attempt to replicate the performance style of Haydn’s time. By severely limiting vibrato, which can obscure inaccuracy, they place a premium on the precision of their intonation. Some of Haydn’s elegance is sacrificed, but the playing is full of sharp, fascinating detail, and while some of their phrasing and accentuation may sound odd, presumably it is boasts the virtue of authenticity. Thus, the cello’s anchor to the three chords that open Op. 76 # 1 linger to underline and thus integrate the opening theme, the canon of the # 2 trio is uncommonly spooky and the energy of the finale of # 5 is especially exhausting. Yet, more than in any other set I’ve heard, the Mosaďques attempt to replicate the performance style of Haydn’s time. By severely limiting vibrato, which can obscure inaccuracy, they place a premium on the precision of their intonation. Some of Haydn’s elegance is sacrificed, but the playing is full of sharp, fascinating detail, and while some of their phrasing and accentuation may sound odd, presumably it is boasts the virtue of authenticity.

- Tokyo Quartet (Koichiro Harada, Kikuei Ikeda, Kazuhide Isomura, Sadao Harada (CBS LP box; Sony Essential Classics CDs, 1978-9) – In light of the remarkable number of fine string players who hail from the Far East, the excellent musicianship of the Toyko Quartet should come as no surprise. Despite their secure mechanics, there's no sense of dutiful fiddling here. Rather, they radiate a thoroughly engaging sense of youthful discovery, invigorating every gesture with ardent enthusiasm that compels renewed appreciation for the extraordinary invention that Haydn poured into these works, at a stage of his life and career when he easily could have fallen back into well-worn routine. Crisp rhythms, bounding excitement, careful enunciation of transitions and structure, and just enough sweetness ensure a light, appropriate balance that stays well within the esthetic of the classical era.

- Alban Berg Quartet (Gunter Pichler, Gerhard Schulz, Thomas Kakuska, Valentin Erben) (EMI, 1996)

- Takász Quartet (Gábor Takász-Nagy, Károly Schranz, Gábor Ormai, András Fejér) (Decca, 1989)

- Eder Quartet (Péter Szüts, János Selmeczy, Sándor Papp, György Éder) (Teldec, 1984)

- Amadeus Quartet (Norbert Brainin, Siegmund Nissel, Peter Schidlof, Martin Lovett) (DG, 3 CD set including Opp. 77 and 103, 1963-70)

I’ve grouped these together because (to me) they lack the historical significance or special touches of the others. They’re all technically secure, played with sufficient enthusiasm, are free of rhetoric, give a good sense of the works, are well-recorded and shouldn’t disappoint. The differences among them seem rather slight. Perhaps appropriately, given its naming in honor of the Viennese modernist who helped humanize twelve-tone writing, the Alban Berg Quartet has a bit more spontaneity, as in the opening of the “Sunrise” which breathes with creative phrasing that animates the score into a living entity, yet their readings have little wit – they’re far from grim, yet tend to be rather serious and focused, although sufficiently swift and light to avoid any feeling of tedium or undue weight. The Takasz have a sweeter sound, in part from their more immediate recording and wider violin vibrato. The Eder, named for its cellist (rather than, as usual, for the first violinist and presumed leader), is slightly more mellow, with a richer, balanced sound. Formed in Britain by Jewish Viennese refugees, the Amadeus compiled a vast catalog of solid recordings during its remarkable 40-year tenure, including 27 quartets by Haydn, which are lean, swift (with few repeats) and imbued with no-nonsense clarity.

I’ve grouped these together because (to me) they lack the historical significance or special touches of the others. They’re all technically secure, played with sufficient enthusiasm, are free of rhetoric, give a good sense of the works, are well-recorded and shouldn’t disappoint. The differences among them seem rather slight. Perhaps appropriately, given its naming in honor of the Viennese modernist who helped humanize twelve-tone writing, the Alban Berg Quartet has a bit more spontaneity, as in the opening of the “Sunrise” which breathes with creative phrasing that animates the score into a living entity, yet their readings have little wit – they’re far from grim, yet tend to be rather serious and focused, although sufficiently swift and light to avoid any feeling of tedium or undue weight. The Takasz have a sweeter sound, in part from their more immediate recording and wider violin vibrato. The Eder, named for its cellist (rather than, as usual, for the first violinist and presumed leader), is slightly more mellow, with a richer, balanced sound. Formed in Britain by Jewish Viennese refugees, the Amadeus compiled a vast catalog of solid recordings during its remarkable 40-year tenure, including 27 quartets by Haydn, which are lean, swift (with few repeats) and imbued with no-nonsense clarity.

- The Lindsays (Peter Cropper, Ronald Birks, Robin Ireland, Bernard Gregor-Smith) (ASV separate CDs, 2000) – The Lindsays’ account is perhaps the most controversial (and that’s a rare thing in the genteel world of chamber music).

Writing for Classicstoday.com, David Hurwitz minces no words, calling them “perverse … focusing on matters of rhythm and accentuation to the exclusion of everything else, including … tonal beauty, dynamics, shading, intonation and structural cohesion. … While I certainly prefer personality and character to blandness, the Lindsays step over the line into caricature. They bury the music with their mannered, neurotic twitching and fidgeting. It's unmusical, unidiomatic, and unpleasant to listen to … .” True, it doesn’t gush with tenderness and it’s a far cry from your grandfather’s image of a kindly, bewigged doddering “Papa Haydn” (and speaking of images, how about that cover!) as well as the focused moderation we have come to expect from British ensembles, but it’s not all that outré and hardly as abrasive and punishing as Hurwitz suggests. Rather, it makes no pretense of being idiomatic, and portions admittedly are overstated. But at the risk of displaying appalling ignorance of “proper” style, I find it riveting, enhanced by extremely close miking that invites you to feel the visceral force of the playing. The Lindsays (that’s what they call themselves) may not serve as a fair introduction to the subtleties of Haydn’s work or the classical string quartet in general, but their informality and iconoclasm provide an unvarnished and colorful take on works that can become overly familiar and afford a compelling change of pace once you become accustomed to other more routine versions. Writing for Classicstoday.com, David Hurwitz minces no words, calling them “perverse … focusing on matters of rhythm and accentuation to the exclusion of everything else, including … tonal beauty, dynamics, shading, intonation and structural cohesion. … While I certainly prefer personality and character to blandness, the Lindsays step over the line into caricature. They bury the music with their mannered, neurotic twitching and fidgeting. It's unmusical, unidiomatic, and unpleasant to listen to … .” True, it doesn’t gush with tenderness and it’s a far cry from your grandfather’s image of a kindly, bewigged doddering “Papa Haydn” (and speaking of images, how about that cover!) as well as the focused moderation we have come to expect from British ensembles, but it’s not all that outré and hardly as abrasive and punishing as Hurwitz suggests. Rather, it makes no pretense of being idiomatic, and portions admittedly are overstated. But at the risk of displaying appalling ignorance of “proper” style, I find it riveting, enhanced by extremely close miking that invites you to feel the visceral force of the playing. The Lindsays (that’s what they call themselves) may not serve as a fair introduction to the subtleties of Haydn’s work or the classical string quartet in general, but their informality and iconoclasm provide an unvarnished and colorful take on works that can become overly familiar and afford a compelling change of pace once you become accustomed to other more routine versions.

Haydn's evolution of the string quartet, the subtleties of which can elude amateurs, has been traced by a number of historian/scholars. Among them, I found these to be extremely insightful and valuable: Haydn's evolution of the string quartet, the subtleties of which can elude amateurs, has been traced by a number of historian/scholars. Among them, I found these to be extremely insightful and valuable:

- Reginald Barrett-Ayres: Joseph Haydn and the String Quartet (Schirmer, 1974) – this is one of those rare books that transcends its nominal subject, placing detailed analyses of each set of quartets in context with astute excursions on musical forms, parallel events and other musicians.

- Paul Griffiths: The String Quartet – A History (Thames & Hudson, 1983).

- Karl Geiringer: Haydn – A Creative Life in Music (Norton, 1946; 2d edition: Doubleday, 1963).

- Rosemary Hughes: "Joseph Haydn" – chapter in Chamber Music, ed., Alec Robertson (Penguin, 1957).

- James Webster – article on Haydn in Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians (2001 edition).

- Reginald Barrett-Ayres: notes to the Aeolian Quartet LP boxes of Opp. 0/1/2 and 76/77/103 (London Stereo Treasury STS-15328/32, 15333/36) – these supplement his book with even more detailed analyses of the individual pieces.

- Laszlo Somfai – notes to the Tatrai Quartet CD sets of Opp. 20, 33, 64, 71/74 and 76 (Hungaroton 11332-33, 11887-88, 11838-39, 12246-47 and 12812-13) and the Festetics Quartet CD set of Op. 9 (Hungaroton 12976-77).

- Istvan Barna – notes to the Tatrai Quartet CD set of Op. 17 (Hungaroton 11382-83) and LP of Op. 77 (Hungaroton SLPX 11776).

- Marc Vignal – notes to the Mosaďques Quartet CD set of Op. 76 (Astrée E 8665).

- Robin Golding – notes to the Lindsay Quartet CD set of Op. 76 (ASV DCA 1077).

- Misha Donat – notes to the Takász Quartet CD set of Op. 76 (London 425 467).

Copyright 2010 by Peter Gutmann

|

Thus, the cello’s anchor to the three chords that open Op. 76 # 1 linger to underline and thus integrate the opening theme, the canon of the # 2 trio is uncommonly spooky and the energy of the finale of # 5 is especially exhausting. Yet, more than in any other set I’ve heard, the Mosaďques attempt to replicate the performance style of Haydn’s time. By severely limiting vibrato, which can obscure inaccuracy, they place a premium on the precision of their intonation. Some of Haydn’s elegance is sacrificed, but the playing is full of sharp, fascinating detail, and while some of their phrasing and accentuation may sound odd, presumably it is boasts the virtue of authenticity.

Thus, the cello’s anchor to the three chords that open Op. 76 # 1 linger to underline and thus integrate the opening theme, the canon of the # 2 trio is uncommonly spooky and the energy of the finale of # 5 is especially exhausting. Yet, more than in any other set I’ve heard, the Mosaďques attempt to replicate the performance style of Haydn’s time. By severely limiting vibrato, which can obscure inaccuracy, they place a premium on the precision of their intonation. Some of Haydn’s elegance is sacrificed, but the playing is full of sharp, fascinating detail, and while some of their phrasing and accentuation may sound odd, presumably it is boasts the virtue of authenticity.