|

Everyone loves a good mystery. Of the fifteen riddles packed into Sir Edward Elgar's 1899 Enigma Variations, the most intriguing one has yet to be solved.

In the annals of English music, Elgar was a true hero.

In the annals of English music, Elgar was a true hero.

Edward Elgar, c. 1900 |

Elgar had little formal instruction and was largely self-taught. Christopher Headington deems it fortunate that his parents could not afford to send him to study abroad, where he would have been molded by foreign influence. Instead, he was enthralled by the resources of his father's music store, where he studied scores and textbooks on his own, and accompanied his father, who was the organist of Worcester Cathedral. Elgar later recalled: “A stream of music flowed through our house and the shop. I was all the time bathing in it.” He became proficient on the cello, bass, piano, bassoon and trombone – and the violin, which he taught. Headington further notes that, as a Catholic, Elgar was largely insulated from the influence of the rigid musical strictures of the English church. Yet in his proper dress, formal bearing and regal conduct Elgar outwardly appeared to be the very model of an English gentleman and the exemplification of Edwardian society.

In keeping with his cherished place in his nation's musical history, more than any other composer Elgar has triggered substantial dispute over the meaning of his “Englishness.” To some it was manifest. Thus, writing in the 1954 edition of Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians, “H.C.C.” contended that: “it is by the direct and constant appeal of Elgar's music to his own countrymen that the English character of his art is abundantly proved.” Ernest Newman proclaimed Elgar “the very soul of our race” and his works “in truth the very voice of England.” Yehudi Menuhin agreed that listeners could recognize in Elgar “the collective soul of a race, set in its own climate and landscape.”

Honored with a stamp ... and a £20 bank note |

Others were not so sure. Alex Cohen, for one, denied that “our composers use exclusively English rhythms, harmonies and orchestral coloring” and doubted that “they by some secret fusion or mingling of the elements of music achieve an amalgam recognizable as English.” Rather, he cautioned that “we stimulate our pride of possession by conveniently ignoring the purely personal idiom and idiosyncrasies of our great men and lumping their characteristics together as 'national.' The greatest works in literature and music cannot be pigeon-holed in their 'national' categories.”

J. B. Priestly delved a bit deeper to posit a more complex artist, chiding those who sneer at Elgar for failing to understand that “the age did not simply consist of the British Empire still untroubled, garden parties, champagne suppers and the Guards on parade,” but rather “confusion, deepening doubt and melancholy whispers from the unconscious, as well as all that hope and glory.” Nalini Ghuman goes further, tracing the very notion of “Englishness” and its perpetuation to nostalgia for the waning imperial past and to British efforts to counter the schisms and dissent bred by colonial expansion.

Statue in Worcester |

Esther Cavett-Dunsby agrees that pigeon-holing Elgar as quintessentially English is paradoxical, since his genius transcended, rather than grew out of, his English predecessors by integrating foreign styles and precedent. In that light, “H.C.C.” contended that Elgar “was never impressed by the doctrine that national music can be synthetically developed from national sources of folk songs and other traditions of the past” but rather that he wrote in “a cosmopolitan language spoken with a personal tone of voice (albeit with a provincial accent).” Harold Schonberg adds that, unlike his Victorian predecessors, Elgar injected an unusual degree of individual personality, as heard in melodies with tension, wide intervals and exuberant leaps.

Among the roots of Elgar's art, Cavett-Dunsby cites the 19th century tone poems of Liszt, Smetana and Strauss, the concerto and symphonic finales of Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven and, of particular significance here, the variations of Brahms, Dvorak, Franck and Tchaikovsky. Interestingly, Percy Sholes notes a direct if rather obscure precedent for the Enigma Variations, although there is no reason to believe that Elgar knew of it: an 1825 Enigma Variations and Fantasia on a Favorite Irish Air for the Piano Forte in the Style of Five Eminent Artists by Cipriani Potter (who later revealed his stylistic models to be Ries, Kalkbrenner, Kramer, Rossini and Moscheles).

While some snubbed Elgar's output as a sentimental, pseudo-romantic relic, he undeniably paved the way for Vaughan Williams, Delius, Walton, Britten and others to revitalize British music. Indeed, rather than spurn his art as derivative Bernard Shaw (actually Irish) unabashedly praised Elgar's “sheer personal originality” and proclaimed him the true symphonic successor to Beethoven, superior to Mendelssohn, Schumann and even Brahms. Shaw especially praised Elgar's orchestration – “No mere effect monger, he … raises every separate instrument to its highest efficiency” – which Adam Carse expands to cite Elgar's clarity in choosing distinctive tone colors for each instrument, minutely-graded inflections and blending of the primary tone colors, overlapping tone colors to avoid sharp contrasts, and an absence of harmonic padding.

![]() Although Elgar had been composing for over a decade, his Enigma Variations was his first grand success and undoubtedly led to his being knighted in 1904. It arose with astonishing speed. He recalled its genesis in a most casual way:

Although Elgar had been composing for over a decade, his Enigma Variations was his first grand success and undoubtedly led to his being knighted in 1904. It arose with astonishing speed. He recalled its genesis in a most casual way:

One evening after a long and tiresome day's teaching, aided by a cigar, I musingly played on the piano the theme as it now stands. The voice of Lady Elgar asked with a sound of approval, “What was that?” I answered, “Nothing – but something might be made of it.” [He then played several variations] and asked, “Who is that like?” The answer was, “I cannot quite say, but it is exactly the way W.M.B. goes out of the room. You are doing something which I think has never been done before.” Thus the work grew into the shape it has now.That was on October 21, 1898. Three days later he wrote to his publisher:

Alice and Edward Elgar, c. 1889 |

I have sketched a set of Variations (orkestry) on an original theme: the Variations have amused me because I've labeled 'em with the nicknames of my particular friends. That is to say, I've written the variations each one to represent the mood of the “party” – I've liked to imagine the “party” writing the var: him (or her) self & have written what I think they wd. have written – if they were asses enough to compose – it's a quality idee & the result is amusing to those behind the scenes & won't affect the hearer who “nose nuffin.” what think you?On October 28 at a weekly teaching session he extemporized a set of variations on his theme and challenged his students to guess whom they represented. He reportedly discarded variations for the composers Charles Parry and Arthur Sullivan that imitated their styles rather than personality traits. On November 1 he played nearly the entire piece for a student.

The full score is dated February 19, 1899. Two days later, hoping for a dramatic boost in his fortunes, Elgar sent it to Hans Richter, the famous Wagner conductor, who was sufficiently intrigued to program it for his upcoming June 19 London concert, where it was received with enormous acclaim. The Musical Times review was ecstatic, hailing its “effortless originality ... combined with thorough savoir faire.” (Alas, the review was hardly impartial; rather it was written by Augustus Jaeger, a representative of Elgar's supportive – and highly motivated – publisher.) Jerrold Northrop Moore proclaims the Enigma Variations “without parallel in the world of music – the announcement of a new creative presence on the world stage has never been made more brilliantly or completely.” Jack Wastrop, though, asserts that the greatest enigma was that such a magnificent work sprang from a composer who, until age 42, had yet to produce a masterpiece.

The first layer of mystery lay in Elgar's prefacing each variation with a cryptic title recognizable only to those familiar with his circle of associates.

The first layer of mystery lay in Elgar's prefacing each variation with a cryptic title recognizable only to those familiar with his circle of associates.  Initially, he sought to dispel any need to identify the references, telling one of the subjects that the Variations: “ought to be considered as absolute music and that any personal allusion only concerned his subjects and himself.” He further claimed that while “the various personalities have been a source of inspiration ... there is nothing to be gained in an artistic or musical sense by solving the enigma of any of the personalities; the listener should hear the music as music and not trouble himself with any intricacies of 'programme.'” Yet in program notes to a 1911 Turino concert, he helped to stoke curiosity:

Initially, he sought to dispel any need to identify the references, telling one of the subjects that the Variations: “ought to be considered as absolute music and that any personal allusion only concerned his subjects and himself.” He further claimed that while “the various personalities have been a source of inspiration ... there is nothing to be gained in an artistic or musical sense by solving the enigma of any of the personalities; the listener should hear the music as music and not trouble himself with any intricacies of 'programme.'” Yet in program notes to a 1911 Turino concert, he helped to stoke curiosity:

This work, commenced in a spirit of humour and continued in deep seriousness, contains sketches of the composer's friends. It may be understood that these personages comment or reflect upon the original theme and each one attempts a solution of the Enigma, for so the theme is called.Elgar finally dispelled speculation and identified all the subjects of his private joke in notes to a 1929 Aeolian piano roll, posthumously expanded in a 1949 36-page booklet, My Friends Pictured Within, in which a photo and description of each individual faced the first page of the autograph score of the matching movement. Interestingly, the variations did not celebrate Elgar's inner circle, as might have been expected, but rather a disparate group of both close and casual acquaintances. (Moore posits that most had recently joined Elgar at the Leeds Music Festival for the premiere of his historical cantata Caractacus two weeks before the evening he described, and thus remained in his mind.) Remarkably, other than Elgar himself, none of his subjects seems known nowadays apart from being memorialized in his score – all the more reason to approach the Variations as absolute music, to be enjoyed purely on its abstract merits without regard to the now-obscure sources of its inspiration.

In its final form, the work comprises a theme and 14 variations. The parenthetical information below following each title names the subject and provides the tempo marking and the timing in Elgar's own 1926 recording. Unless otherwise attributed, all quotations are the composer's.

Theme (Andante – 1:34) – In 1912 Elgar explained that the theme represents

The Enigma theme with fully-annotated expression |

I – C.A.E. (Caroline Alice Elgar – l'Istesso tempo – 2:05) – While Norman Del Mar describes the composer's wife Alice (as she was known) on the basis of pictures as a “homely, old-fashioned lady,” Milton Cross asserts, far more importantly, that she encouraged the fledgling composer, focused him on a serious musical career and had such taste and judgment that she became his most discriminating critic, on whose judgments he came to rely and whose practical advice he followed.

Enigmas I (C.A.E.), II (H.D.S.-P.) and III (R.B.T.) (all photos [except Weaver] from My Friends Within) |

II – H.D.S.-P. (Hew David Steuart-Powell – Allegro – 0:44) – To honor the pianist in Elgar's trio, the violins plunge forward with scampering 16th notes as the lower strings test more mellow extended phrases that barely hint at a melody about to emerge and soon abandon the effort. While William Mann contends that the agitated chromatic notes reflect the pianist's sight-reading troubles, Elgar recalled that before beginning to play Steuart-Powell would warm his fingers “with a characteristic diatonic run over the keys,” which Elgar humorously transforms into chromatic phrases “beyond H.D.S.-P.'s liking.”

III – R.B.T. (Richard Baxter Townsend – Allegretto – 1:26) – According to Michael De-La-Noy, Townsend was a non-musical eccentric who rode a tricycle, ringing a bell so people could hear him coming. Apparently, during amateur theatricals he impersonated an old man with a deep voice that kept breaking into his natural high falsetto, to the great amusement of the audience. A sinuous clarinet and bassoon melody spiked by syncopated bursts and string pizzicatos suggests gentle ribbing. Curiously, his variation also contains the only repeated section in the entire work, although the significance of that device in this context is unclear.

IV – W.M.B. (William Meath Baker – Allegro di molto – 0:31) – Noy identifies Baker as Townsend's brother-in-law who owned an inn and gave quick, decisive orders while organizing activities for his guests.

IV (W.M.B.), V (R.P.A.) and VI (Ysobel) |

V – R.P.A. (Richard Penrose Arnold – Moderato – 1:53) – The son of the famous literary critic and poet Matthew Arnold, Richard “played [the piano] in a self-taught manner, evading difficulties but suggesting in a mysterious way the real feeling. His serious conversation was continually broken up by whimsical and witty remarks.” His variation, in c-minor, is considerably darker yet flowing, with a livelier middle section emulating his nervous laugh in a rhythm of “ha-ha-HA, ha-ha-HA-ha-ha” that quickly subsides into the initial ruminations and leads directly to ...

VI – Ysobel (Isabel Fitton – Andantino – 1:22) – While the linkage to Arnold's variation is unclear, Fitton's immediately brightens into C major. She was a viola student of Elgar and the opening is intended to depict “an exercise for crossing the strings, a difficulty for beginners.” Elgar described her as tall and graceful, seeming to float rather than walk, and apparently was taken with her charm and beauty, intending her music to be “pensive and, for a moment, romantic.” Aptly, a solo viola plays her languid melody at the very top of its register, as if yearning for something alluring but out of reach, perhaps suggesting Elgar's feelings toward her.

VII – Troyte (Arthur Troyte Griffith – Presto – 0:54) – Griffith was an abrupt and opinionated architect. His variation bounds in with an escalating insistent timpani figure that launches a scamper among furious string scales and assertive brass and comes to a brusque close.

VII (Troyte), VIII (W.N.) and IX (Nimrod) |

VIII – W.N. (Winifred Norbury – Allegretto – 1:42) – A neighbor who accompanied Elgar when he tried out new works (he on violin, she on piano), Norbury lived with her sister in an 18th century home. To Elgar, “the gracious personalities of the ladies are sedately shown,” together with “a little suggestion of her characteristic laugh.” To Moore, the minuet reflects the charm of the Norbury home, to William Mann the length of the musical phrases suggests that Winifred was a great talker, and to Irving Kolodin this quiet interlude reflects her calming place among Elgar's friends.

IX – Nimrod (Augustus Johannes Jaeger – Adagio – 2:52) – As liaison to Elgar's publisher Novello, Jaeger was an untiring advocate for Elgar's work, which Elgar deeply appreciated. As for the title, Jaeger was born in Germany, “jäger” means “hunter” in German, and Nimrod was a mighty hunter in Genesis. His variation, set in the “noble” key of E-flat, was intended as “a record of a long summer evening talk when my friend Jaeger grew nobly eloquent – as only he could – on the grandeur of Beethoven and especially his slow movements. ... The opening bars were made to suggest the slow movement of Beethoven's Pathetique [Sonata].” By placing “Nimrod” at the very center of the work, Elgar crafts a deeply felt and intensely moving tribute to his closest friend, second only to his wife in his affections. Indeed, the theme of this variation is nearly identical to the opening, thus drawing a special musical intimacy with the composer. “Nimrod” is the only section of the Variations that tends to be performed in isolation, often at solemn occasions.

X – Intermezzo – Dorabella (Dora Penny – Allegretto – 2:53) – A close friend who would turn pages for Elgar as he played at the piano,

X (Dorabella), XI (G.R.S., with Dan) and XII (B.G.N.) |

XI – G.R.S. (George Robert Sinclair – Allegro di molto – 0:51) – Sinclair was the organist at Hereford Cathedral, but Elgar contended that the variation “has nothing to do with organs or cathedrals or, except remotely, with G.R.S.” Rather, Dr. Perry Hull, who succeeded Sinclair at Hereford, explained that the opening depicted Sinclair's bulldog Dan rushing about a riverbank, plunging in, paddling after a stick Sinclair had thrown in, and growling with joy as he seized hold of it. Martin Bookspan hears Dan's barking in the brass figures. A friend of Sinclair thought that the variation captured Sinclair's “'prancing walk' – a quick pace but with stiffness in it.” In any event, it's breathlessly paced and full of coiled energy.

XII – B.G.N. (Basil G. Nevinson – Andante – 2:16) – Dominated by cellos, from which a soloist occasionally breaks free, this variation is for the cellist in the trio with Elgar and Steuart-Powell (Variation II) – “a tribute to a very dear friend whose scientific and artistic attainments, and the whole-hearted way they were put at the disposal of his friends, particularly endeared him [to me].” Elgar's reference to science might have been to Nevinson's activity as an entomologist who reportedly assembled an enormous collection of 140,000 beetles.

XIII – Romanza: *** (Lady Mary Lygon[?] – Moderato – 2:05) – Elgar later asserted that this variation referred to Lady Mary Lygon, a wealthy aristocrat active in local music festivals whose patronage he might have sought, but others are unsure. The standard assumption is that, as a reflection of his extreme sensitivity for propriety, Elgar left this title temporarily nameless until he could get Lady Lygon's permission, as he mistakenly thought her to have left on a long sea voyage to Australia, where her brother was to be installed as the colonial governor. He left some intriguing clues: “the soft tremor of the drums suggests the distant throb of the engines of a[n ocean] liner” and “the quiet undulations of the violas suggest the peaceful motion of the water.” Moore further notes that the clarinet quotes a phrase from Mendelssohn's Calm Sea and Prosperous Voyage Overture.

XIII (Mary Lygon? Helen Weaver?) |

XIV – Finale: E.D.U. (Elgar – Allegro – 4:33) – An intimate riddle that mystified most of his colleagues, the initials here turned out to stand for Alice's pet name for the composer – Edoo. Fittingly the longest and most complex variation, Elgar described it well: “Written at a time when friends were dubious and generally discouraging as to the composer's musical future, this variation is merely to show what E.D.U. intended to do. References are made to two great influences on the life and art of the composer – C.A.E. and Nimrod. [Indeed, it melds the themes of variations I and IX.] The whole work is summed up in the triumphant broad presentation of the theme in the major.” Cross adds: “The composer speaks of his illusions and frustrations, dreams and ideals. The principal theme is given exultantly. The organ [in its only appearance] enters with majestic peals as if to confirm Elgar's faith in life and art.”

As originally written, the finale was to have ended rather abruptly. But after the first performance, Jaeger thought it was too short and urged Elgar to extend it and to even add “Finale” to the main title. Elgar quipped that if E.D.U. was not logically developed, it would be an accurate self-portrait and resisted lengthening it on the ground that he already had exhausted G Major and so dwelling further on that single key would sound too Schubertian. But he ultimately capitulated. Perhaps reflecting his relief, Elgar quoted Longfellow for an epigraph on the final page: “Great is the art of beginning, but greater the art is of ending.” And so, Moore notes, after his journey of discovery through friends Elgar returns to his point of departure with the themes of his wife and finally himself, concluding with a highly appropriate affirmation of his own self-image (although to some it might sound a bit too weighty and prolonged in contrast to the lean efficiency of the preceding portions). The quandaries of the individual titles, while once perplexing, have all been solved (with the possible exception of XIII). As Glenn Gould quipped, they “provided a diverting parlor game for the musical equivalent of the Bloomsbury set” – at least until Elgar published the definitive key. But there remains a far greater puzzle for which Elgar dropped only the barest of hints. Having intrigued scholars for over a century, it still appears to be impenetrable.

The quandaries of the individual titles, while once perplexing, have all been solved (with the possible exception of XIII). As Glenn Gould quipped, they “provided a diverting parlor game for the musical equivalent of the Bloomsbury set” – at least until Elgar published the definitive key. But there remains a far greater puzzle for which Elgar dropped only the barest of hints. Having intrigued scholars for over a century, it still appears to be impenetrable.

Here, the composer, who was enamored of riddles, ciphers and cryptograms, was far less helpful.  Elgar's program note for the 1899 premiere contained a deliberately obscure tease: “The 'Enigma' I will not explain – its 'dark saying' must be left unguessed, and I warn you that the apparent connection between the Variations and the Theme is often of the slightest texture; further, through and over the whole another and larger theme 'goes' but is not played.” Moore points out that each of the variations does indeed contain at least the germ of the initial theme. But the “another and larger theme [that] 'goes' but is not played” remains elusive, although not for lack of effort.

Elgar's program note for the 1899 premiere contained a deliberately obscure tease: “The 'Enigma' I will not explain – its 'dark saying' must be left unguessed, and I warn you that the apparent connection between the Variations and the Theme is often of the slightest texture; further, through and over the whole another and larger theme 'goes' but is not played.” Moore points out that each of the variations does indeed contain at least the germ of the initial theme. But the “another and larger theme [that] 'goes' but is not played” remains elusive, although not for lack of effort.

The earliest and most rudimentary attempts at solutions all assumed that the hidden theme served as a musical counterpoint to the principal theme, and perhaps to some, if not most, of the variations. That approach was triggered by Elgar himself, who told the Musical Times in October 1900 that “the heading Enigma is justified by the fact that it is possible to add another phrase, which is quite familiar, above the original theme … .” Among the “quite familiar” tunes proposed, the front-runner was “Auld Lang Syne,” which at least has the added benefit of words that appropriately convey nostaglic sentiment. Others (in many cases accompanied by annotated scores detailing the purported points of congruence) have been: “Rule Britannia,” “Pop Goes the Weasel,” “Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star” [itself derived from the French folk song “Ah! vous dirai-je, maman”], the slow movement of Mozart's “Prague” Symphony, the Dies Irae plainchant, Chopin's Nocturne in g minor and the revered name of “Bach” (in German musical notation: B-flat, A, C, B-natural). Whenever presented with a purported solution, Elgar steadfastly derided it. Toward the end of his life, he rejected a suggestion of “God Save the Queen”: “Of course not, but it is so well-known that it is extraordinary no-one has found it.”

Others have proposed more creative, if obscure, musical solutions:

- Stephen Pickett considered the enigma to be a decryption for “Rule Britannia,” as each letter appears in one of the abbreviations Elgar assigned to the variations (GRS, EDU, HeLen, DorabElla, etc.).

- Andrew Moodie enciphered the name of Elgar's daughter Carice in musical notation (so that after A through G, H becomes “A,” I becomes “B,” etc.) to yield “CADBCE'' and then shows that the theme (transposed to a-minor = CADB) and numerous other motifs are derived from it and its retrograde, inversion and transpositions.

- Martin Gough asserted that the hidden theme is a puzzle canon (also called a canon aenigmaticus [“enigmatic canon”], in which only the leading voice is annotated, leaving the other parts to be realized through clues) based on the primary theme itself, which, in turn, accompanies a larger theme by Thomas Tallis that fits in counterpoint with every one of the variations.

that Elgar never really said that the hidden “phrase” or “theme” was musical, and so it could be literary, abstract or symbolic. That opens the floodgates to some wildly creative, if circuitous and wholly speculative, solutions. Among the most intriguing:

that Elgar never really said that the hidden “phrase” or “theme” was musical, and so it could be literary, abstract or symbolic. That opens the floodgates to some wildly creative, if circuitous and wholly speculative, solutions. Among the most intriguing:

- Del Mar, Mann and De-La-Noy all felt that the work is unified by an underlying theme of friendship, mainfested as a cross-section of the society in which Elgar developed and functioned.

- Byron Adams submitted that the enigma is one of identity – the complex interaction between the composer's outer, rigid, socially-conforming male and inner, emotional, sensitive female personalities which he was able to explore by projecting himself into the souls of others.

- C. R. Santa noted that the g-minor scale degrees of the first four notes are 3-1-4-2, a common decimal approximation of the mathematical constant pi and that in his notes to the 1929 Pianola roll Elgar referred to two quavers, two crochets and a drop of a seventh, or 22/7, the fractional approximation of pi. Santa further linked Elgar's reference to a “dark saying” to the nursery rhyme of “four and twenty blackbirds baked in a pie [=pi].”

- Edmund M. Greene contended that each variation corresponds to a line of Shakespeare's Sonnet 66. Thus, line 9 (“And art made tongue-tied by authority”) corresponds to Dorabella's stutter, line 11 (“And simple truth miscalled simplicity”) refers to B.B.N.'s scientific attainments and line 12 (“And captive good attending captain ill”) invokes the sea voyage of ***.

- Robert W. Padgett first insisted upon Bach's Ein Feste Burg but then presented the most complex analysis of all, resulting in a revelation made a few months before the genesis of the Variations. I could not hope to paraphrase his reasoning:

In measure 6 is an oddly-placed double bar marking the end of something other than the Enigma Theme which concludes in measure 17. In these opening six measures only the string quartet plays: Violin I, Violin II, Viola and Cello. Adding up the notes for each of these active parts produces number totals that are easily matched to corresponding letters in the alphabet. Based on the formula in which 1 = A, 2 = B, 3 = C and so on, the note totals [12, 15, 17, 24] produce LOQX. This is the phonetic equivalent of locks, a term suggesting the presence of multiple keys, and by extension, ciphers. Applying the formula in reverse in which Z = 1, Y = 2, X = 3 and so on, the same note totals produce the letters LOJC. In the Bible the term lo means to look, gaze, or behold. JC are the initials for Jesus Christ. Together LOJC may be read as “Behold Jesus Christ.” By combining the plaintext results of the cipher going forwards (LOQX) and backwards (LOJC) in the alphabet, a third solution emerges: LOOX LQ JC. This phrase (or 'dark saying') reads as “Looks like JC,” or “Looks like Jesus Christ.” This solution is an apt description of the miraculous image on the Turin Shroud first revealed by Secondo Pia's famous photographic negative in May 1898.

And then there are the skeptics, beginning with Newman in 1939, who consider the whole idea of an unsolved puzzle to be a hoax, the mischievous prank of a composer who had a lifelong love of solving and creating all types of conundra. Indeed, Elgar titled the work merely “Variations on an Original Theme” and the first references to an enigma came only later. (Del Mar asserts that the superscription “enigma” over the opening theme in the autograph is not even in Elgar's handwriting.) In that spirit, Glenn Gould insisted that the solution was P.D.Q. Bach's “Songs Without Points,” which he claimed results in perfect harmony when each theme is applied to it as a cantus firmus without any need for transposition or metrical alteration – “incontrovertible evidence that the greatest English composer of his day paid tacit tribute to the most imaginative of his German predecessors.” Of course, both P.D.Q. and his composition are wholly fictitious!

Given the vast gulf among purported solutions, their irreconcilable nature and the adamant conviction of their proponents, it seems reasonable to assume that the underlying enigma will never be solved. Indeed, the only folks who really knew or might have known the answer, if in fact there was one (Elgar, Alice and perhaps Jaeger and Penny) all took that knowledge to their graves. While efforts undoubtedly will persist, the true glory of the Enigma Variations surely lies not in the challenge of its impenetrable riddle but in the music itself that compels and amply merits attention. After all, despite our natural fascination with sources of inspiration or extrinsic references, all music ultimately stands on its intrinsic merit.

A key to presenting the Variations may lie in its composer's personality. According to Shaw: “A less pretentious person than Elgar could not be found. …

A key to presenting the Variations may lie in its composer's personality. According to Shaw: “A less pretentious person than Elgar could not be found. …

[You could] talk to him for a week without suspecting that he is anything more than a very typical English country gentleman who does not know a fugue from a fandango.” Newman contends: “Few conductors suffer as much … from their uncomprehending interpreters than Elgar does. His exquisite sensitiveness is turned into sentimentality, his high spirits into vulgarity, his nobilmente into theatrical bombast – all because the conductor does not know where to stop.” Elgar told Newman that the proper expression is written into the music and that all a conductor has to do is to follow those directions. Indeed, Elgar left us extensive interpretive directions, as the score is full of dynamic, tempo and expressive indications. Even so, in 1935 the Times contended that: “No doubt, writing in the 1890's, Elgar was given to over-marking expressive nuances as an insurance against the haphazard treatment he was liable to receive from the English orchestras of the day.” Elgar himself urged that his music should be played “elastically and mystically.”

Elgar's first acoustical recording sessionFortunately, we have a far more reliable guide to Elgar's interpretive intent than hints derived from his personality and anecdotal statements and even the score itself – his two recordings. Although he reportedly struggled at first, Elgar apparently was considered sufficiently accomplished to merit appointment as the Principal Conductor of the London Symphony Orchestra in 1911. Lewis Forman credits him with changing the perception of British conductors, who until then gave an impression of being ponderous and self-satisfied, whereas Elgar had a calm demeanor and developed exacting demands for nuance. (Alas, he was fired after one season; while the London Symphony board cited numerous health issues, that may have been a pretext for Elgar's poor drawing power in others' works, with which he reportedly was ill at ease and garnered mixed reviews.) Schonberg asserts that after his creative period ended following Alice's death Elgar focused on conducting his own works, with the auspicious consequence that we have both acoustical and electrical Elgar-led recordings of most of his major pieces.

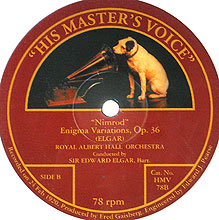

Edward Elgar, The Symphony Orchestra [sic] (1920-1921, HMV 78s, 26:15); Royal Albert Hall Orchestra (1926, HMV 78s, EMI CD, 27:20)

Timothy Day reported that Elgar loved listening to his own recordings, even the acoustical ones that falsified the instrumentation, texture and overall sound. Thus in 1917 he proclaimed (admittedly for the Gramophone promotional house magazine): “The records of my own compositions conducted by me are remarkably faithful reproductions of the originals.” He became an advocate of recordings to foster appreciation of great music, and his enthusiastic participation undoubtedly helped bolster the legitimacy of the industry.

Elgar began recording his works in 1914,

beginning with the freshly-composed Carissima and continuing mostly with other short, light pieces, plus heavily abridged four-sided (16-minute) versions of his 50-minute Violin Concerto (1916, with Marie Hall) and half-hour Cello Concerto (1919, with Beatrice Harrison). In May 1919 he recorded the “Nimrod” and “Dorabella” movements of the Variations as a double-sided 78, presumably intended to present the most popular sections, but recut them in February 1920, added three more sides containing the theme and first eight variations in November 1920 and cut the remainder on three further sides in May 1921 to generate the first complete recording. (Various sources report prior single- or double-sided issues of excerpts, but I've never encountered any of them.) After the acoustical system was replaced with electrical recording Elgar re-cut the Variations in April and August 1926 to produce the first electrical album. The two sets are essentially similar, the difference in overall timing due mainly to a major cut in the famed Nimrod section in order to squeeze it onto the same side as Dorabella in the acoustical version. (The R.B.T. repeat and the rambling Intermezzo, both of which would have survived unharmed by trimming, are given intact.) While the acoustical pickup was quite good, the textures and dynamics are conveyed more fully in the electrical remake.

beginning with the freshly-composed Carissima and continuing mostly with other short, light pieces, plus heavily abridged four-sided (16-minute) versions of his 50-minute Violin Concerto (1916, with Marie Hall) and half-hour Cello Concerto (1919, with Beatrice Harrison). In May 1919 he recorded the “Nimrod” and “Dorabella” movements of the Variations as a double-sided 78, presumably intended to present the most popular sections, but recut them in February 1920, added three more sides containing the theme and first eight variations in November 1920 and cut the remainder on three further sides in May 1921 to generate the first complete recording. (Various sources report prior single- or double-sided issues of excerpts, but I've never encountered any of them.) After the acoustical system was replaced with electrical recording Elgar re-cut the Variations in April and August 1926 to produce the first electrical album. The two sets are essentially similar, the difference in overall timing due mainly to a major cut in the famed Nimrod section in order to squeeze it onto the same side as Dorabella in the acoustical version. (The R.B.T. repeat and the rambling Intermezzo, both of which would have survived unharmed by trimming, are given intact.) While the acoustical pickup was quite good, the textures and dynamics are conveyed more fully in the electrical remake.Despite his admonition to others to strictly follow the score, Elgar himself takes substantial expressive liberties with the tempos. Sir Adrian Boult recalled that “no composer-conductor varied more than Elgar in his interpretations of his own works from year to year,” and indeed the theme and variations I, III, VIII and X are considerably faster in the remake (balanced out by notably slower V, VII, XII and XIII). While the tempo variances fall into no meaningful pattern, both versions are fully convincing with ample feeling, but moderate and balanced, within a context of nobility and dignity. Even if the rather discrete portamenti (curiously, more pronounced in the remake) are dismissed as a period relic, Elgar's unwritten inflections are not only gratifying in their own right but provide a hugely valuable supplement to the score itself – both as a baseline and a model for others – even though Elgar may have mellowed somewhat in the decades between writing and recording the Variations.

Henry Wood, New Queen's Hall Orchestra (1924, Columbia 78s, 24:20); New Queen's Hall Orchestra (1936, Columbia 78s, Pearl CD, 27')

Second in importance only to Elgar's own recordings of the Variations are those of Henry Wood,

the most esteemed British conductor of his time (and who nearly gave the premiere). Both his recordings (including the only other acoustical one) were with the house orchestra of the Promenade Concerts, which he instituted in 1893 at the then-newly-opened Queen's Hall, London's foremost concert venue famed for its excellent acoustics, and which he led as the “Proms” for a half-century (until the hall was destroyed in the blitzkrieg, yet the cherished Proms tradition was revived and lives on to this day). At first Wood was known as a strict disciplinarian – he eliminated the “deputy system” in which the regular players routinely sent substitutes so as to accept more lucrative outside engagements. Despite his orchestra's reputation as the best in London, according to Robert Philip, Wood himself was considered merely basic, unsophisticated and “rough-and-ready,” emphasizing quantity over quality (in part due to the inadequacy of three rehearsals for six weekly Proms concerts). Elgar was no fan – in 1924 he slammed a Wood performance of the Beethoven Eroica as “commonplace and stupid.” Yet Wood's late acoustical recordings of major works display bold personality – a bounding, vigorous and propulsive (albeit abridged) Haydn “Surprise” Symphony, a virile Schubert Unfinished (also abridged), and a full-length Franck Symphony in d that surges with tense energy (and, alas, a decent but less inspired Tchaikovsky Pathetique).

the most esteemed British conductor of his time (and who nearly gave the premiere). Both his recordings (including the only other acoustical one) were with the house orchestra of the Promenade Concerts, which he instituted in 1893 at the then-newly-opened Queen's Hall, London's foremost concert venue famed for its excellent acoustics, and which he led as the “Proms” for a half-century (until the hall was destroyed in the blitzkrieg, yet the cherished Proms tradition was revived and lives on to this day). At first Wood was known as a strict disciplinarian – he eliminated the “deputy system” in which the regular players routinely sent substitutes so as to accept more lucrative outside engagements. Despite his orchestra's reputation as the best in London, according to Robert Philip, Wood himself was considered merely basic, unsophisticated and “rough-and-ready,” emphasizing quantity over quality (in part due to the inadequacy of three rehearsals for six weekly Proms concerts). Elgar was no fan – in 1924 he slammed a Wood performance of the Beethoven Eroica as “commonplace and stupid.” Yet Wood's late acoustical recordings of major works display bold personality – a bounding, vigorous and propulsive (albeit abridged) Haydn “Surprise” Symphony, a virile Schubert Unfinished (also abridged), and a full-length Franck Symphony in d that surges with tense energy (and, alas, a decent but less inspired Tchaikovsky Pathetique).Wood's acoustical recording of the Variations is a fine companion to Elgar's own, exhibiting much of the same fine adjustment of tempos, together with lovely balances, a robust presentation of inner voices, brass accents and timpani, precise articulation and a keen sensitivity to the mood of each section. The recording is somewhat less atmospheric than Elgar's, yet with better fidelity, avoiding sonic congestion in the densely-scored finale. One curious aspect – Wood bypasses the repeat in Variation III, presumably out of artistic choice rather than technical necessity, as it would have only added another half-minute to the first side (containing the Theme and variations I, II and III) for a total time of 4.1 minutes while the very next side (with IV, V, VI and VII) runs 4.3 minutes. (Frankly, I've never appreciated the need for the III repeat, as it results in two identical climaxes that are awkward in their own right and seem to have no connection to the personality of its subject.)

In any event, Wood gets off to a quicker start and his overall pacing is notably swifter than Elgar's. His 1936 electrical remake tends to intensify the tempos, so that the quicker variations (III, VII and XI) fly by even faster and all but one (XII) of the others become more relaxed.

In any event, Wood gets off to a quicker start and his overall pacing is notably swifter than Elgar's. His 1936 electrical remake tends to intensify the tempos, so that the quicker variations (III, VII and XI) fly by even faster and all but one (XII) of the others become more relaxed.Not surprisingly, in light of Elgar's vaunted position in the English musical pantheon, most of the first half-century of recordings of the Variations were by British conductors and orchestras. Perhaps out of respect for cherished traditions, they tend to adhere rather closely to the composer's own approach:

- Hamilton Harty, Hallé Orchestra (1932, Columbia 78s, 26:45)

The excellence of the Hallé Orchestra tended to pull the center of British musical gravity from London to Manchester, abetted by its cavalcade of superstar chief conductors who preceded (Richter, Beecham) and followed (Sargent, Barbirolli) Harty's reign (1920 – 1933). His Enigma is surprisingly moderate when compared to his other recordings of major works – a Dvorak “New World” Symphony that crackles with vitality, a heavily-inflected yet lyrical Schubert “Unfinished,” muscular Haydn symphonies that belie the “Papa Haydn” indulgence of the time, and a zesty, propulsive Mendelssohn “Italian” Symphony. From the very outset, Harty presents the Theme with exquisitely molded string phrases and then surges ahead with the central wind section but never cedes emotional control, imparting even the fast sections with a patrician sheen (although his Troyte becomes a wild scramble, haphazardly articulated at his break-neck tempo). While actually Irish, Harty adheres overall to a smooth, eminently “civilized” British approach of attentive reserve, while opening the interpretive door just enough to pave the way for more iconoclastic readings that eventually would come from an influx of outside traditions, beginning with ...

- Arturo Toscanini, BBC Symphony Orchestra (1935, EMI CD, 28:35); NBC Symphony Orchestra (1951, RCA LP, BMG CD, 29:14)

Toscanini's visits to London rekindled a surge of cultural chauvinism that provides a fascinating opportunity to revisit the concept of musical nationalism. As recounted by Joseph Horowitz, the press sniped that the Italian “clearly misunderstood” Elgar and Neville Cardus called him “a cultivated foreigner speaking the English language.” Yet his defenders rose up as well.

While conceding his “non-English accent,” Newman wrote that Toscanini's Enigma “soared to a height and plumbed a depth I have never known it to approach.” Leading British conductors, presumably experts in their national culture, agreed. Adrian Boult called it “a great experience” with “what seems to be inevitably the right musical language” and Landon Ronald hailed it as the finest performance he had ever heard and “exactly as Elgar intended.” While praising Elgar's own renditions, Ronald conceded: “Toscanini excelled because he has a genius for conducting and Elgar has not.” Many commentators have subsequently offered explanations for the appeal and validity of Toscanini's approach. Joseph Horowitz explains that while Toscanini's work may not have been idiomatic, it was that very factor that led him to apply fresh insight to bypass others' interpretive gloss: “its indiscriminate detergent action makes worn goods emerge glistening clean.” Mortimer Frank points to “its flair for the dramatic, its plateaus of contrast from one variation to another, and its shaping and building of climaxes,” which Harris Goldsmith traces to Toscanini's background in opera and the theater. Spike Hughes cites “superb conviction, genuine feeling for lyrical passages [and] tremendous, irresistible rhythmic impetus,” and concludes that when all is said and done one could not care less whether the music sounded English or Eskimo.

While conceding his “non-English accent,” Newman wrote that Toscanini's Enigma “soared to a height and plumbed a depth I have never known it to approach.” Leading British conductors, presumably experts in their national culture, agreed. Adrian Boult called it “a great experience” with “what seems to be inevitably the right musical language” and Landon Ronald hailed it as the finest performance he had ever heard and “exactly as Elgar intended.” While praising Elgar's own renditions, Ronald conceded: “Toscanini excelled because he has a genius for conducting and Elgar has not.” Many commentators have subsequently offered explanations for the appeal and validity of Toscanini's approach. Joseph Horowitz explains that while Toscanini's work may not have been idiomatic, it was that very factor that led him to apply fresh insight to bypass others' interpretive gloss: “its indiscriminate detergent action makes worn goods emerge glistening clean.” Mortimer Frank points to “its flair for the dramatic, its plateaus of contrast from one variation to another, and its shaping and building of climaxes,” which Harris Goldsmith traces to Toscanini's background in opera and the theater. Spike Hughes cites “superb conviction, genuine feeling for lyrical passages [and] tremendous, irresistible rhythmic impetus,” and concludes that when all is said and done one could not care less whether the music sounded English or Eskimo.Tony Harrison notes that Toscanini had rebelled against recording larger works in individual 78 rpm side chunks and so, beginning with a June 3, 1935 concert that included the Variations (and Wagner's Faust Overture and Brahms's Symphony # 4), the EMI engineers undertook to record him live using relays of overlapping disc cutters. Despite the excellence of the results, Toscanini refused to approve them, and so they were released only posthumously (although he soon would relent and participate in formal BBC recording sessions from 1937 to 1939, and NBC sessions from 1938 until his retirement in 1954). Heard today, Toscanini's Variations boasts a plastic molding of phrases and subtle tempo variations that temper elemental energy with an aura of spontaneity unmatched in his first NBC broadcast presentation (February 4, 1939), which seems tentative in comparison, unlike the majority of his broadcasts near the outset of his relationship with his American orchestra. By the time Toscanini cut his only studio Variations in late 1951 with the NBC Symphony his simplified approach had smoothed out much of the nuance of his earlier work in favor of a stronger sense of momentum and overall drive which, while thrilling in itself, falls short of the vibrancy and intense involvement of the BBC concert. If Toscanini seems to lavish particular devotion upon the lower string parts, and especially the solos in VI, XII and XIII, it likely stems from his early career as a cellist.

In the meantime, recordings continued from British conductors and orchestras:

In the meantime, recordings continued from British conductors and orchestras:

Adrian Boult, BBC Symphony (1936, HMV 78s, VAI CD, 26:10); London Philharmonic (1953, HMV); London Philharmonic (1961, World Record Club); London Symphony (1971, EMI LP, 30:00) – To Boult goes the unique distinction of four studio Enigmas – on 78s, mono LP, stereo mail-order LP and a final EMI rendition. A prominent conductor known for his taste and restraint, in his first outing Boult conjures excellent playing from the BBC orchestra (which, after all, he founded) and adheres closely to the score with only occasional hints of champing at the bit. The lovely reading builds to a thrilling finale and has a “modern” sound by eliminating all traces of portamento. Typical of recordings of the time, the timpani are barely audible.

Boult's final recording of the Variations benefits from far improved sound and is considerably more leisurely. Indeed in places it seems rather autumnal – understandably so, as he was 82 at the time. Inherent merit aside, it stands as a vital historical monument – the final statement of the last-surviving conductor who knew, extensively worked with, and was deeply admired by Elgar.

Malcolm Sargent, National Symphony (1945, Decca 78s, Dutton CD); London Symphony (1953, Decca LP, 30:15); Philharmonia (1960, HMV LP, 30:30) – Sargent, too, led Enigma studio recordings for evolving media – first on 78s, then on LP and finally in stereo. Known as a passionate advocate for the music of his native country (with particular enthusiasm for Elgar's choral works) and a severe taskmaster (and thus not especially liked by musicians), he was reputed for careful preparation and the precision of his performances. Despite the use of different orchestras, his Enigmas are all unerringly played. The mono LP is the most fully characterized (and boasts typically magnificent Decca fidelity) while the stereo LP builds through forthright preliminary variations to an especially imposing Nimrod and then subsides to a deeply moving Romanza.

John Barbirolli, Hallé Symphony Orchestra (1948, HMV 78s, 26:10); Hallé Symphony Orchestra (1956, Pye LP, 27:55); Philharmonia Orchestra (1963, EMI/Angel LP, 30:50) – Barbirolli, too, cut three studio recordings of the Enigma within 15 years. After a rough detour as Toscanini's successor at the New York Philharmonic (admittedly impossibly huge shoes to have filled), he returned to his native England and resurrected both his and the Hallé's reputations over the next quarter century. As is evident from the timings alone, his three Enigmas follow the usual progression of a maturing conductor – the first is fleet and incisive, the last, while hardly stodgy, is more considered and atmospheric (and embraces the more polished sound of the Philharmonia), and the middle one combines the most attractive qualities of the others in a winning balance of ardor and reflection.

George Weldon, Philharmonia Orchestra (1954, English Columbia LP, 32:10) – Poor George – he appears to be the only British musician we've named so far (plus most of those to come) who hasn't been knighted. Far less known or remembered than his compatriots, reportedly modest, nice and outpaced by more ambitious colleagues, Weldon led the Birmingham orchestra for seven years until ousted by rumors. His Variations are patiently paced and noble, yet acutely attentive, with exceptional care to bring out the full complement of instrumental textures. Surging with multiple crests and especially heartfelt is his rendition of Nimrod, to which he must have felt a particular bond, as he requested to have it played at his funeral.

Thomas Beecham, Royal Philharmonic (1955, Columbia LP, 30:25) – Perhaps it was a matter of ego, but despite their parallel urbane personalities the most famous of all British conductors had surprisingly little enthusiasm for the most famous British composer. And despite his reputation for stimulating his players to heights of lyricism and spontaneity, evident in a few sections (a heartfelt Nimrod, a bounding GRS, a gracious Dorabella), Beecham's only recording of the Variations, with the orchestra he had founded a decade earlier, sounds rather routine and aloof, further hampered by mediocre sonics.

Colin Davis, London Philharmonic (1965, Philips LP, 33:10); London Symphony Orchestra (2007, LSO Live CD, 33:05) – One more British recording before the floodgates of foreigners opened … Even though the tempos are steadily deliberate, Davis's recording is fully characterized, deeply felt, radiantly played and vividly recorded. Remarkably, he repeated the feat 42 years later with a virtually identical reading, recorded in concert and released on the London Symphony's own CD label.

While it would be interesting to compare Enigmas led by conductors representing other national schools, only three issued prior to the 1970s (aside from Toscanini,

While it would be interesting to compare Enigmas led by conductors representing other national schools, only three issued prior to the 1970s (aside from Toscanini,

whose unique approach was rarely regarded as authentically Italian) were by conductors from outside the English mainstream, although their credentials as belonging to a national school of interpretation were hardly intact.

whose unique approach was rarely regarded as authentically Italian) were by conductors from outside the English mainstream, although their credentials as belonging to a national school of interpretation were hardly intact.Walter Goehr, Concert Hall Symphony Orchestra (1953, Concert Hall LP, 30:05) – After spending his first three decades in Berlin, Goehr was exiled in 1932 and based the rest of his career in London. Perhaps out of deference to his pick-up recording orchestra, his leadership is cautious, with no hint of the philosophical rumination considered the essence of the German romantic style. Sonic sludge obscures textural detail and conveys little evidence of timpani.

William Steinberg, Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra (1960, Capitol LP, 29:25) – Steinberg, too, was trained and launched his career in Germany, was summarily ousted by the Nazis, and emigrated – to America, where his most enduring post was his quarter-century in Pittsburgh. Their Variations reflects neither his native background nor the pioneering energy of his adopted home but rather present the score in a solid, thoroughly idiomatic reading of which any British conductor could be proud.

Pierre Monteux, London Symphony Orchestra (1961, Decca, 29:35) – Nor is it surprising that Monteux, famed for his penchant for leading any work credibly and idiomatically, eschews all but a trace of his diffident French accent. Universally adored by musicians, he effortlessly and persuasively conveys the essence of the Variations in rich sonority with barely any embellishment. Equally fascinating is the Variations that Monteux led with the Symphony of the Air – the remnant of Toscanini's NBC Symphony Orchestra that persevered as a conductorless ensemble – at the Toscanini memorial concert in Carnegie Hall on February 5, 1957, displaying uncharacteristic lean textures and sharp attacks, perhaps in tribute to the departed Maestro's own style (Music and Arts CD, 27:50).

Only in the 1970s did the Variations attract an eclectic set of interpreters on record who hailed from non-British traditions – Eugene Ormandy/Philadelphia Orchestra (1972), Zubin Mehta/Los Angeles Philharmonic, Eugen Jochum/London Symphony, Bernard Haitink/London Philharmonic (all 1975), Georg Solti/Chicago Symphony and Daniel Barenboim/London Philharmonic (both 1976). But by then, the burgeoning advances in communication and transportation had broken down the former cultural barriers to create the less distinctive pan-national style to which we have become accustomed. Even so, among them were a precious few that presented personal outlooks:

Only in the 1970s did the Variations attract an eclectic set of interpreters on record who hailed from non-British traditions – Eugene Ormandy/Philadelphia Orchestra (1972), Zubin Mehta/Los Angeles Philharmonic, Eugen Jochum/London Symphony, Bernard Haitink/London Philharmonic (all 1975), Georg Solti/Chicago Symphony and Daniel Barenboim/London Philharmonic (both 1976). But by then, the burgeoning advances in communication and transportation had broken down the former cultural barriers to create the less distinctive pan-national style to which we have become accustomed. Even so, among them were a precious few that presented personal outlooks:Leopold Stokowski, Czech Philharmonic (1975, London Phase Four LP, 32:10)

Taped in concert together with a half-dozen intensely-wrought Bach orchestral transcriptions in July 1972

(but not released until 1975), this was Stokowski's only recorded Enigma as well as his only recording with the Czech Philharmonic, renowned for the distinctive sound of each of its instrumental choirs. Typical of his inexhaustible enthusiasm for new challenges, he tackled this new venture at age 90! Elgar may have painted his Variations in pastels, but Stokowski renders them in Technicolor. Others personalize the Variations with adjustments of tempo and phrasing and Stokowski does so as well, but adds the additional fascination of spotlighting Elgar's shifting instrumental textures for which the Czech orchestra was so well-equipped. The result may strike traditionalists as inapt and even vulgar but others will revel in the discoveries inherent in a piece we thought we knew all too well – the winds prattle merrily in II, the cymbals send out cascades of water spray in VII, the shrill flutes in VIII gently mock the ladies' chatter, the deep brass add gravity to IX, the clarinets underscore the mystery of XIII. After all, the Enigmas was widely hailed for its bold orchestration, so why not fully display it? We might also mention that, although never “officially” released (but readily available on YouTube), an even more dramatic account came from a most unexpected source – Eugene Ormandy, freed from the lush, if rather impersonal, sound of his Philadelphia Orchestra, conducting the Boston Symphony in a stunningly trenchant July 14, 1964 concert (28:15).

(but not released until 1975), this was Stokowski's only recorded Enigma as well as his only recording with the Czech Philharmonic, renowned for the distinctive sound of each of its instrumental choirs. Typical of his inexhaustible enthusiasm for new challenges, he tackled this new venture at age 90! Elgar may have painted his Variations in pastels, but Stokowski renders them in Technicolor. Others personalize the Variations with adjustments of tempo and phrasing and Stokowski does so as well, but adds the additional fascination of spotlighting Elgar's shifting instrumental textures for which the Czech orchestra was so well-equipped. The result may strike traditionalists as inapt and even vulgar but others will revel in the discoveries inherent in a piece we thought we knew all too well – the winds prattle merrily in II, the cymbals send out cascades of water spray in VII, the shrill flutes in VIII gently mock the ladies' chatter, the deep brass add gravity to IX, the clarinets underscore the mystery of XIII. After all, the Enigmas was widely hailed for its bold orchestration, so why not fully display it? We might also mention that, although never “officially” released (but readily available on YouTube), an even more dramatic account came from a most unexpected source – Eugene Ormandy, freed from the lush, if rather impersonal, sound of his Philadelphia Orchestra, conducting the Boston Symphony in a stunningly trenchant July 14, 1964 concert (28:15).Leonard Bernstein, BBC Symphony Orchestra (1982, DG LP and CD, 38')

Admired by iconoclasts but reviled by traditionalists, Bernstein's sprawling take is the least idiomatic of all Enigma recordings yet fascinating in its own right, illuminating the familiar warhorse with a fresh, if challenging, approach. As documented in an ICA Classics video, rehearsals to prepare for his only outing with the venerable BBC ensemble became a tense confrontation between a headstrong interpreter proselytizing the immutable truth of his novel vision and an established institution firmly adhering to the intransience of its own culture, exacerbated by resistance to Bernstein's attempts to leaven condescension with humor. Bernstein prevailed, as the performance itself is a bold, compelling venture realized with commitment and splendor.

While the faster sections are taken at a nearly normal pace, they sharply contrast with the others, beginning at the very outset with the theme (1:59, compared to Elgar's 1:34), and culminating with XII (3:29 v. 2:16), XIII (3:25 v. 2:05) and the finale (6:14 v. 4:33). The utmost extreme is IX (7:12 v. 2:52), apparently intended as a profound meditation on Nimrod's friendship but emerging as funereal with a climax more oppressive than potent. To the artists' credit, despite their misgivings the playing is brilliant, from the exquisite tenderness of the end of I to the brass snarls of VII. Although largely ignoring the tempo indications, Bernstein faithfully observes the expressive markings of the score, providing a unique opportunity to dwell upon the felicities of its construction. While his efforts to inject emotional depth and gravity may be anathema to the English temperament, and while, as some have quipped, the result is more caricature than characterization, Bernstein's vision is undeniably unique and dares us to take a fresh look at a familiar work. Giuseppe Sinopoli and the Philharmonia soon would follow suit with a somewhat similar but less boldly impassioned reading (1984, DG, 34:15) but with a somewhat more standard four-minute Nimrod and a broader W.N.

While the faster sections are taken at a nearly normal pace, they sharply contrast with the others, beginning at the very outset with the theme (1:59, compared to Elgar's 1:34), and culminating with XII (3:29 v. 2:16), XIII (3:25 v. 2:05) and the finale (6:14 v. 4:33). The utmost extreme is IX (7:12 v. 2:52), apparently intended as a profound meditation on Nimrod's friendship but emerging as funereal with a climax more oppressive than potent. To the artists' credit, despite their misgivings the playing is brilliant, from the exquisite tenderness of the end of I to the brass snarls of VII. Although largely ignoring the tempo indications, Bernstein faithfully observes the expressive markings of the score, providing a unique opportunity to dwell upon the felicities of its construction. While his efforts to inject emotional depth and gravity may be anathema to the English temperament, and while, as some have quipped, the result is more caricature than characterization, Bernstein's vision is undeniably unique and dares us to take a fresh look at a familiar work. Giuseppe Sinopoli and the Philharmonia soon would follow suit with a somewhat similar but less boldly impassioned reading (1984, DG, 34:15) but with a somewhat more standard four-minute Nimrod and a broader W.N.Roger Norrington, SWR Radio-Sinfonieorchester Stuttgart (2010, Haenssler CD, 31:45)

Speaking of iconoclastic approaches to the Variations, Norrington, famed as a pioneer and paradigm of the historically-informed performance movement, extended his initial interest in reviving authentic practices of the baroque and classical eras through the late romantics and here applies to the Variations his current fixation of replacing the “continuous vibrato of the 20th century” with “pure tone.” While this approach certainly clarifies the harmonies, the resulting sound is rather austere and a bit bland. Like Bernstein, he tends to broaden the tempos as the work progresses, and he doesn't follow the score literally. On the one hand, reticence might seem to invoke the composer's personality as well as the ideal temperament of his era and homeland, and the lighter sections gain a lovely diffident simplicity (VIII, X) or a measure of special dignity (Nimrod) suitable to their subjects. But unlike with prior musical epochs, there's little need for speculation as to how Elgar might have wanted his work to sound, as we have the creator's own recordings as models, and they're far more free and emotionally charged than the attempted restoration presented here.

While Elgar would go on to produce oratorios, symphonies and concerti that are well-respected, performed and recorded, it is his Enigma Variations (along with his even lighter Pomp and Circumstance Marches) that is – and most likely will remain – his most popular and universally-admired work.

The most comprehensive source for all things Elgarian is the Elgar Society, which has generously made the entire contents of its bi-monthly Journal available free on-line (http://elgar.org/elgarsoc/archive/). While I accept full blame for the musical judgments in this article, I am indebted to the following sources for the information, references and quotations:

The most comprehensive source for all things Elgarian is the Elgar Society, which has generously made the entire contents of its bi-monthly Journal available free on-line (http://elgar.org/elgarsoc/archive/). While I accept full blame for the musical judgments in this article, I am indebted to the following sources for the information, references and quotations:- On Elgar:

- Carse, Adam: History of Orchestration (Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co., 1925)

- Cross, Milton: Encyclopedia of the Great Composers and Their Music (Doubleday, 1953)

- De-La-Noy, Michael: Elgar, the Man (Viking, 1984)

- Headington, Christopher: History of Western Music (Bodley Head, 1974)

- Moore, Jerrold Northrup: Edward Elgar: A Creative Life (Oxford, 1984)

- Schonberg, Harold: Lives of the Great Composers (Norton, 1981)

- Shaw, Bernard: The Great Composers: Reviews and Bombardments (Louis Compton, ed.) (U California Press, 1978)

- On “Englishness”:

- Cohen, Alex: “Elgar and Englishness” (Elgar Society Journal 12:4)

- Ghuman, Nalini: “The Third 'E' – Elgar and Englishness” (Elgar Society Journal 15:3)

- “H.C.C.”: article on Elgar in Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians (Grove, 1954 edition)

- Langford, Samuel: “Elgar and Englishness” (Elgar Society Journal 12:4)

- Priestly, J. B.: “Elgar and Englishness” (Elgar Society Journal 12:4)

- On the Variations:

- Blamires, Ernest: “Loveliest, Brightest, Best – a Reappraisal of 'Enigma' Variation XIII” (Elgar Society Journal 14:2)

- Cavett-Dunsby, Esther: Preface to Eulenburg score (Eulenburg, 19xx)

- Del Mar, Norman: Conducting Elgar (Clarendon, 1998)

- Mann, William: notes to Barbirolli/Philharmonia LP (Angel S 36120, 1963)

- Sholes, Percy: Oxford Companion to Music (9th Edition, Oxford, 1955)

- On Solving the Enigmas:

- Adams, Byron: “The 'Dark Saying' of the Enigma: Homoeroticism in the Elgarian Paradox” in S. Fuller and L. Whitsell, eds: Queer Episodes in Music and Western Identity (University of Illinois, 2002)

- Elgar, Sir Edward: My Friends Pictured Within (Novello, [undated])

- Gould, Glenn: The Glenn Gould Reader (Tim Page, ed.) (Knopf, 1984)

- Greene, Edmund M.: “Elgar's 'Enigma': a Shakespearean Solution” (Elgar Society Journal 13:6)

- Moodie, Andrew: “Elgar's 'Enigmas' – a Solution: (Elgar Society Journal 13:6)

- Padgett, Robert W.: “Elgar's Enigma Theme Unmasked (http://enigmathemeunmasked.blogspot.com/2011/06/links-between-enigma-variations-and.html)

- Pickett, Steven: “Elgar's 'Enigmas' – a Decryption?” (Elgar Society Journal 13:6)

- Santa, C. R.: “Solving Elgar's Enigma” (Current Musicology 89 (Spring 2010))

- On Conductors and Recordings:

- Day, Timothy: A Century of Recorded Music – Listening to Musical History (Yale, 2000)

- Forman, Lewis: “Picturing Elgar and His Contemporaries as Conductors: Elgar Conducts at Leeds” (Elgar Society Journal 15:6)

- Frank, Mortimer: Arturo Toscanini: The NBC Years (Amadeus, 1992)

- Goldsmith, Harris: notes to Toscanini/NBC CD (RCA/BMG 60287 2, 1991)

- Harrison, Tony: notes to Toscanini/BBC CD (EMI 7 69184 2, 1987)

- Horowitz, Joseph: Understanding Toscanini – A Social History of American Concert Life (University of California, 1994)

- Hughes, Spike: The Toscanini Legacy (Putnam, 1959)

- Philip, Robert: Performing Music in the Age of Recording (Yale, 2014)

- Van den Hoogen, Eckhardt: notes to Norrington/SWR CD (Haenssler 93191, 2011)

As for the recordings themselves, it seems appropriate to acknowledge the bounty available through on-line sites. (Let me be clear: I do not use or condone sites offering unlicensed downloads of currently-available – and even new – CDs. Such sites are not only illegal but unethical, as they steal well-deserved income from artists and legitimate distributors and undermine the commercial incentive to continue their valuable work.) YouTube, Spotify and devoted fans who restore and make available older records that are neglected by copyright owners but deserve to be remembered and cherished, all enabled me to transcend the resources of my own collection and local libraries to hear the vast majority of the performances cited in this article, and thus expand its scope. (Indeed, without these resources I never would have been able to cover the entire first two-dozen Enigma recordings and then sample many of the others.) Beyond serving as an invaluable base for research, they open the door wide for us all to simply enjoy the vast realm of what is, after all, our shared cultural heritage.

Copyright 2016 by Peter Gutmann

copyright © 1998-2016 by Peter Gutmann. All rights reserved.