|

|

The broadway show is America's true classical music, boasting our finest composition, lyrics, drama, acting, dance and stagecraft rolled into one. Here's a survey of a dozen favorites.

|

In a previous column, I had looked to the New York Philharmonic's sweeping “American Celebration” box set as a key to defining American classical music. That effort ultimately failed, defeated by the huge profusion of material we embrace as our own. But perhaps I looked in the wrong place. And, coming from New York, I should have known better.

“Classical” means art music. When a folk singer bemoans social injustice, or a blues wailer the world's cruelties, or a torch vocalist her broken heart we respond because we feel it as spontaneous, heartfelt and personal. But when an opera diva warbles such things, we know that every note is precisely scripted, every inflection carefully planned and every gesture fully rehearsed. Art isn't supposed to be real; rather, it's a heavily stylized form of expression. Yet, we respond to it even more deeply because it's the culmination of everything our culture has to offer.

Our true classical music is the Broadway show. It's the American opera - our finest music, lyrics, drama, acting, dance and stagecraft rolled into one. Despite their wide range of settings, characters and plots, our Broadway shows created an experience to which generations of Americans looked for the ultimate expression of our culture. And, like European opera, their appeal transcended high art - the songs often crossed over to become huge popular hits. Now, in retrospect, they serve both as a floodlight to illuminate the trends and outlooks of the past century and as a mirror to reflect the enduring ideals upon which our present culture is based.

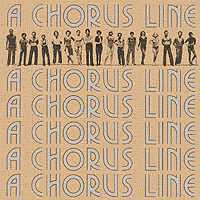

For this brief and highly subjective survey I've picked a dozen personal favorites. I've included two which you won't find on many other lists, while omitting others that, while hugely popular and widely admired, I've just never liked that much (Guys and Dolls, The Most Happy Fella, Man of La Mancha) or which in retrospect don't seem all that significant (Camelot, Hair, The King and I). I've relied principally upon Broadway cast recordings, which inevitably slight all other elements at the expense of the songs but which usually comprise our most reliable remnant of the original productions. I've disregarded movie adaptations, though - some are faithful (Oklahoma, The Music Man) but most are awkward attempts to translate a work conceived in one medium into another with vastly different resources and means; indeed, a few (Cabaret, On the Town, A Chorus Line) made radical changes that supplant memories of the original shows.

Show Boat (music by Jerome Kern; lyrics by Oscar Hammerstein II; first produced in 1927) - Show Boat is widely regarded as the first truly great American musical.  Its substantial plot, epic scope, complex characters and serious social subtext were a tremendous leap forward from the previous fluff of amorous flirtations among the idle rich (affectionately satirized in Sandy Wilson's The Boy Friend). Audiences knew from the very opening that something significant was about to unfold, as two choruses sing of cotton blossoms - black workers lament the burden of carrying bales of the stuff, while white revelers anticipate the show they're about to see on the riverboat of that name. Rather than the usual complement of one or at most two memorable songs, its score is rich with a half-dozen, including “Make Believe,” “Can't Help Lovin' Dat Man,” “You Are Love,” “Life Upon the Wicked Stage,” “Bill,” and the stunning “Old Man River”. The lyrics were accessible and vernacular, yet truly profound: Its substantial plot, epic scope, complex characters and serious social subtext were a tremendous leap forward from the previous fluff of amorous flirtations among the idle rich (affectionately satirized in Sandy Wilson's The Boy Friend). Audiences knew from the very opening that something significant was about to unfold, as two choruses sing of cotton blossoms - black workers lament the burden of carrying bales of the stuff, while white revelers anticipate the show they're about to see on the riverboat of that name. Rather than the usual complement of one or at most two memorable songs, its score is rich with a half-dozen, including “Make Believe,” “Can't Help Lovin' Dat Man,” “You Are Love,” “Life Upon the Wicked Stage,” “Bill,” and the stunning “Old Man River”. The lyrics were accessible and vernacular, yet truly profound:

I get weary and sick of tryin',

I'm tired of livin' and scared of dyin',

But Old Man River, he just keeps rollin' along.

The records cut by the original cast, with excerpts from subsequent revivals, are on Pearl GEMM 0060 (2 CDs), but, typical of the time, many pieces were trimmed to fit 78 side restrictions and were altered into fox trots for dancing. Ironically, then, it's the many revivals that provide our most authentic souvenirs of the original Showboat conception (despite the need to update the book and lyrics which, even for their era, contained disturbingly frequent use of the "n-word"). Of these, a 1962 studio set with John Raitt, Barbara Cook and William Warfield (now on Sony CD SK 61877) is nicely done and contains a selection of older sides as well.

Oklahoma (Richard Rodgers, Oscar Hammerstein II; 1943) - Despite its innovations, Show Boat was about show folk, and thus its music was an amalgam of old operetta styles.  Oklahoma was about real people doing real things. The opening “Oh, What a Beautiful Mornin’” was a waltz, but one that shone with the clarity of the sun warming cornfields and open plains. With only a single exception (“It's a Scandal,” wisely cut from the album and movie), the score is magnificent, every song replete with the wholesome spirit of our pioneers. The plot is unmistakably American and the characters symbolize the great forces that shaped our nation's history - the love between rancher Curly and farmer's daughter Laurie reconciles the two conflicting economic forces that settled the West, hired hand Jud Fry embodies the grueling labor of Westward expansion, peddler Ali Hakim stands for the influx of immigrants, the lusty shenanigans of Will Parker and Ado Annie represent the irrepressible youthful energy that fueled it all, and the folksy wisdom, loneliness and sacrifices of widow Aunt Eller provide the spiritual backbone for the emerging community. It's the story of America in a nutshell. When Curly ardently avows his vision for the future, he isn't a mere actor, but he's speaking for every one of our parents - and for each of us as well. While stars of previous shows had cut a few sides, as a measure of its importance Oklahoma was the first American show to boast an integral original cast album. Although not recorded until seven months after the opening and despite downsizing a few items to fit on a 78 side, it bursts with a fervor that must have thrilled its audiences, from the crisp electrifying energy of the Overture through its legendary hits: “Oh, What a Beautiful Mornin',” “Surrey With the Fringe on Top,” “Kansas City,” “People Will Say We're in Love” and the title anthem. Issued on six 78s (and eventually on 45s and LP), it was so successful (the entire album hit the Billboard Pop Chart) that a second volume was issued in 1945 with the rest of the numbers - the largely-forgotten “Lonely Room,” which immeasurably humanizes the monstrous Jud; two sides of “The Farmer and the Cowman” production number; and - ugh! - “It's a Scandal.” All are included on the current CD (Decca 157 981) which boasts remarkably clear sound, far preferable to the murk of an earlier issue (MCA 10798). Oklahoma was about real people doing real things. The opening “Oh, What a Beautiful Mornin’” was a waltz, but one that shone with the clarity of the sun warming cornfields and open plains. With only a single exception (“It's a Scandal,” wisely cut from the album and movie), the score is magnificent, every song replete with the wholesome spirit of our pioneers. The plot is unmistakably American and the characters symbolize the great forces that shaped our nation's history - the love between rancher Curly and farmer's daughter Laurie reconciles the two conflicting economic forces that settled the West, hired hand Jud Fry embodies the grueling labor of Westward expansion, peddler Ali Hakim stands for the influx of immigrants, the lusty shenanigans of Will Parker and Ado Annie represent the irrepressible youthful energy that fueled it all, and the folksy wisdom, loneliness and sacrifices of widow Aunt Eller provide the spiritual backbone for the emerging community. It's the story of America in a nutshell. When Curly ardently avows his vision for the future, he isn't a mere actor, but he's speaking for every one of our parents - and for each of us as well. While stars of previous shows had cut a few sides, as a measure of its importance Oklahoma was the first American show to boast an integral original cast album. Although not recorded until seven months after the opening and despite downsizing a few items to fit on a 78 side, it bursts with a fervor that must have thrilled its audiences, from the crisp electrifying energy of the Overture through its legendary hits: “Oh, What a Beautiful Mornin',” “Surrey With the Fringe on Top,” “Kansas City,” “People Will Say We're in Love” and the title anthem. Issued on six 78s (and eventually on 45s and LP), it was so successful (the entire album hit the Billboard Pop Chart) that a second volume was issued in 1945 with the rest of the numbers - the largely-forgotten “Lonely Room,” which immeasurably humanizes the monstrous Jud; two sides of “The Farmer and the Cowman” production number; and - ugh! - “It's a Scandal.” All are included on the current CD (Decca 157 981) which boasts remarkably clear sound, far preferable to the murk of an earlier issue (MCA 10798).

Carousel (Rodgers and Hammerstein, 1945) - Set among the fisher-folk of Maine, R&H's follow-up to Oklahoma features an equally fine but even more essential score  that plunges deeper into human emotion, intensifies character and advances the narrative rather than merely pausing to elaborate a point already made in the story. “If I Loved You,” “Mister Snow,” “June is Bustin' Out All Over,” “This Was a Real Nice Clambake,” “What's the Use of Wondrin',” “When the Children Are Asleep” and “You'll Never Walk Alone” are capped by the astounding “Soliloquy,” in which the male lead, a carnival barker, explores the implications of his new fatherhood and ultimately resolves to grasp his responsibilities - an amazingly virtuostic profusion of nine melodies packed into seven minutes that manages to make complete dramatic sense. Another innovation was the replacement of an overture with an opening pantomime to the gorgeous “Carousel Waltz,” during which a carnival is assembled on stage. But while many undoubtedly get choked up, I'm afraid that I react with a different reflex to the cloying story and especially the contrived ending, which have never managed to pass my personal gag quotient. The music, though, remains magnificent, especially as performed with complete conviction by John Riatt, Jan Clayton and the other creators of the roles. And perhaps in recognition of its importance, the set was issued on 12 inch 78s (usually reserved for classical releases), rather than the usual 10-inch sides, so as to avoid abridging the complex song intros. The CD reissue (MCA 10799) has three outtakes that are instructive - ask a jazzman to play a song twice and each time he'll fascinate with improvisatory variation, but here the pairs of takes are virtually identical down to all but the smallest detail. That's not necessarily a compliment, but in this context it does serve as an example of what art entails - a focused effort to perfect an expression which can then be repeated verbatim for multiple audiences. that plunges deeper into human emotion, intensifies character and advances the narrative rather than merely pausing to elaborate a point already made in the story. “If I Loved You,” “Mister Snow,” “June is Bustin' Out All Over,” “This Was a Real Nice Clambake,” “What's the Use of Wondrin',” “When the Children Are Asleep” and “You'll Never Walk Alone” are capped by the astounding “Soliloquy,” in which the male lead, a carnival barker, explores the implications of his new fatherhood and ultimately resolves to grasp his responsibilities - an amazingly virtuostic profusion of nine melodies packed into seven minutes that manages to make complete dramatic sense. Another innovation was the replacement of an overture with an opening pantomime to the gorgeous “Carousel Waltz,” during which a carnival is assembled on stage. But while many undoubtedly get choked up, I'm afraid that I react with a different reflex to the cloying story and especially the contrived ending, which have never managed to pass my personal gag quotient. The music, though, remains magnificent, especially as performed with complete conviction by John Riatt, Jan Clayton and the other creators of the roles. And perhaps in recognition of its importance, the set was issued on 12 inch 78s (usually reserved for classical releases), rather than the usual 10-inch sides, so as to avoid abridging the complex song intros. The CD reissue (MCA 10799) has three outtakes that are instructive - ask a jazzman to play a song twice and each time he'll fascinate with improvisatory variation, but here the pairs of takes are virtually identical down to all but the smallest detail. That's not necessarily a compliment, but in this context it does serve as an example of what art entails - a focused effort to perfect an expression which can then be repeated verbatim for multiple audiences.

South Pacific (Rodgers and Hammerstein, 1949) - This show had perfect timing, tapping into America's euphoria over the recent War victory, yet respecting lingering sadness over our losses.  Amid servicemen stationed in the South Pacific who yearn for the things we take for granted, love blooms between a “Cock-Eyed Optimist” Kansas nurse and a world-weary French plantation owner (and, more tragically, between a sailor and a local girl). The plot struck a deeply patriotic chord with both vets and those who stayed at home, while the exotic location made the serious undertones of xenophobia and racism seem less threatening. The music ranges from a children's ditty (“Dites-Moi”) to a deeply-moving operatic aria (“This Nearly Was Mine”). It also reflects an American jolted into reality by the War - while Oklahoma had teased audiences with the wonders of “Kansas City” and a girl who “Cain't Say No,” South Pacific boiled with the repressed lust of horny sailors pining that “There Is Nothing Like a Dame” and replaced prairie petticoats with Mary Martin taking an on-stage shower to “Wash That Man Right Outta My Hair.” South Pacific also had perfect casting. Although many have tried, no one has ever sung “Some Enchanted Evening” as touchingly as Metropolitan Opera bass Ezio Pinza nor “Bali Ha'i,” dripping with misty atmosphere, as movingly as Juanita Hall. (Ironically, the current CD reissue (on Sony 60722) unwittingly illustrates the point - a bonus track has Pinza's dreadful assault on “Bali Ha'i” as he woodenly declaims, “Most-pee-pull-leeve-on-a-lone-lee-eye-land.”) OK, this has begun to read like a tribute to Rodgers and Hammerstein, but they were the greatest and most influential creators Broadway has ever seen. While it's time to change course, before taking leave we should note their 1951 King and I (Decca 158 982), a further slice of exotica with more intimately-scaled music. Amid servicemen stationed in the South Pacific who yearn for the things we take for granted, love blooms between a “Cock-Eyed Optimist” Kansas nurse and a world-weary French plantation owner (and, more tragically, between a sailor and a local girl). The plot struck a deeply patriotic chord with both vets and those who stayed at home, while the exotic location made the serious undertones of xenophobia and racism seem less threatening. The music ranges from a children's ditty (“Dites-Moi”) to a deeply-moving operatic aria (“This Nearly Was Mine”). It also reflects an American jolted into reality by the War - while Oklahoma had teased audiences with the wonders of “Kansas City” and a girl who “Cain't Say No,” South Pacific boiled with the repressed lust of horny sailors pining that “There Is Nothing Like a Dame” and replaced prairie petticoats with Mary Martin taking an on-stage shower to “Wash That Man Right Outta My Hair.” South Pacific also had perfect casting. Although many have tried, no one has ever sung “Some Enchanted Evening” as touchingly as Metropolitan Opera bass Ezio Pinza nor “Bali Ha'i,” dripping with misty atmosphere, as movingly as Juanita Hall. (Ironically, the current CD reissue (on Sony 60722) unwittingly illustrates the point - a bonus track has Pinza's dreadful assault on “Bali Ha'i” as he woodenly declaims, “Most-pee-pull-leeve-on-a-lone-lee-eye-land.”) OK, this has begun to read like a tribute to Rodgers and Hammerstein, but they were the greatest and most influential creators Broadway has ever seen. While it's time to change course, before taking leave we should note their 1951 King and I (Decca 158 982), a further slice of exotica with more intimately-scaled music.

Kismet (Alexander Borodin / Robert Wright and George Forrest, 1953) - Kismet has the most wondrous score of any musical and with good reason. With all due respect to Irving Berlin, Jerome Kern, Richard Rodgers, Cole Porter and company, the best melodies of all time were written by the great romantic classical composers. Kismet was adapted from the symphonic, piano, chamber and operatic bounty of Russian Alexander Borodin (1833 - 1887). Its fantastic tale of a miraculous day in the life of a beggar-poet is pure exotic escapism, but peopled with wincingly outdated “comically” sadistic Arab stereotypes (“Gesticulate” is a hymn to a hand about to be cut off and “Was I Wazir?” catalogues tortures inflicted upon an evil ruler's enemies). In keeping with its origins and setting, the music and its arrangements are lavish, sensuous and brilliantly complex, from rousing chorales and whirling dances to exquisite love songs and philosophical musings. “And This Is My Beloved,” although adapted from a string quartet, is the equal of any opera aria. The lyrics, too, are dazzlingly literate. Take the poet's introduction (“Rhymes Have I”): Jerome Kern, Richard Rodgers, Cole Porter and company, the best melodies of all time were written by the great romantic classical composers. Kismet was adapted from the symphonic, piano, chamber and operatic bounty of Russian Alexander Borodin (1833 - 1887). Its fantastic tale of a miraculous day in the life of a beggar-poet is pure exotic escapism, but peopled with wincingly outdated “comically” sadistic Arab stereotypes (“Gesticulate” is a hymn to a hand about to be cut off and “Was I Wazir?” catalogues tortures inflicted upon an evil ruler's enemies). In keeping with its origins and setting, the music and its arrangements are lavish, sensuous and brilliantly complex, from rousing chorales and whirling dances to exquisite love songs and philosophical musings. “And This Is My Beloved,” although adapted from a string quartet, is the equal of any opera aria. The lyrics, too, are dazzlingly literate. Take the poet's introduction (“Rhymes Have I”):

To a world too prone to be prosaic,

I bring my own panacea -

An iota of iambic and a tittle of trochaic,

Added to a small amount of onomatopoeia.

They sure don't write them like that anymore! And how about this lilting paean to the sheer musicality of words (“Night of My Nights”):

Play on the cymbal, the timbal, the lyre;

Play with appropriate passion. Fashion

Songs of delight and delicious desire

For this night of my nights.

The recording with Alfred Drake, Doretta Morrow and Richard Kiley (Sony SK 89252) is gorgeously sung and superbly detailed.

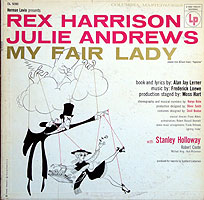

My Fair Lady (Frederick Lowe / Alan Jay Lerner, 1956) - A Broadway show arouses different expectations in each patron. For those who seek sheer delight without even a hint of a serious theme, My Fair Lady is the perfect choice.  It's based on George Barnard Shaw's updating of Pygmalion, the Greek myth of a sculptor who falls in love with his statue. Shaw skewered British class distinctions as a prim sexist phonetics professor bets that he can pass off a Cockney flower girl as a proper lady just by teaching her diction and manners. You can guess the rest - he succeeds only too well and succumbs to the charm he's created. The tunes are wonderful, including “Wouldn't It Be Loverly,” “With a Little Bit of Luck,” “The Rain in Spain,” “Show Me,” “Get Me to the Church on Time,” “I've Grown Accustomed to Her Face” and the ravishing “I Could Have Danced All Night.” Perhaps in keeping with the hero's vocation, the lyrics are splendidly witty and urbane, as when Professor Higgins urges the superiority of his gender to deal with a crisis in “A Hymn to Him” (British accent, please): It's based on George Barnard Shaw's updating of Pygmalion, the Greek myth of a sculptor who falls in love with his statue. Shaw skewered British class distinctions as a prim sexist phonetics professor bets that he can pass off a Cockney flower girl as a proper lady just by teaching her diction and manners. You can guess the rest - he succeeds only too well and succumbs to the charm he's created. The tunes are wonderful, including “Wouldn't It Be Loverly,” “With a Little Bit of Luck,” “The Rain in Spain,” “Show Me,” “Get Me to the Church on Time,” “I've Grown Accustomed to Her Face” and the ravishing “I Could Have Danced All Night.” Perhaps in keeping with the hero's vocation, the lyrics are splendidly witty and urbane, as when Professor Higgins urges the superiority of his gender to deal with a crisis in “A Hymn to Him” (British accent, please):

Would I start crying like a bathtub overflowing?

Or carry on as if my home were in a tree?

Would I run off and never tell me where I'm going?

Why can't a woman [...two-beat pause...] be like me?

Although hindsight truly is 20/20, it still seems incredible that Columbia cut the original cast recording in mono long after the advent of home stereo tape playback and as the rollout of stereo LPs was imminent. Fortunately, in exchange for investing in the show Columbia received perpetual recording rights, and finally recut the album in stereo in February 1959 using the London cast. Rex Harrison as the professor, Julie Andrews as Lisa Doolittle and Stanley Holloway as her scheming father all reprise their roles with more inflection and deeper characterization. But even beyond one disastrous substitution who bleats the gorgeous “On the Street Where You Live” through his nose, something crucial was lost in the export. This is an American show - since the Revolution we've never tired of satirizing our former rulers - and loses its edge when the British wind up ribbing themselves. Overall, the earlier version (Sony CK 5090) is more musical and, surprisingly, better recorded (especially on CD, in which heavy overload distortion afflicts the remake on Sony SK 60539).

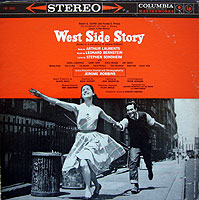

West Side Story (Leonard Bernstein / Stephen Sondheim, 1957) - The unlikely concept of transplanting Romeo and Juliet into New York gang warfare produced the height of Broadway art, a stunningly effective confluence of creative juices  to integrate music, drama and dance to convey a compelling story of tragic romance. Arthur Laurents's book captured the lingo of the streets, Stephen Sondheim's lyrics were understated and utterly convincing, Leonard Bernstein's score soared from the wonder of first love to tragic fury, and huge portions of the show were devoted to Jerome Robbins's expressive ballets. The result shattered so many of the traditional rules. Consider the intermission break. Typically, while problems are implied, first acts end on a hopeful upbeat. Here, a dexterous and buoyant Quintet in which two angry gangs, two ardent but forbidden lovers and a sultry girlfriend sing of their conflicting aspirations plunges into a fatal knife fight. As a siren wails, the shocked survivors scramble off, leaving two corpses sprawled on the bare pavement. A deathly gong tolls over a dry xylophone trill as the dim street lighting fades to black, an urban requiem for shattered dreams that left audiences stunned. This show had attitude and ultimately would spawn Hair and other productions that challenged conventional stories and techniques. But that lay well into the future - indeed, its two great themes of immigrant assimilation and generational conflict would be treated again the very next year with gentle humor in Flower Drum Song. The best reflection of the bold concept is the original cast recording, cut three days after the opening, which bristles with scrappy energy (Sony SK 60724). Although much of the ardor remains in the 1960 soundtrack recording (Sony SK 48211), Bernstein's 1985 remake (DG 457 199) is ill-conceived as the grand opera he never wrote, howlingly miscast and ploddingly paced. to integrate music, drama and dance to convey a compelling story of tragic romance. Arthur Laurents's book captured the lingo of the streets, Stephen Sondheim's lyrics were understated and utterly convincing, Leonard Bernstein's score soared from the wonder of first love to tragic fury, and huge portions of the show were devoted to Jerome Robbins's expressive ballets. The result shattered so many of the traditional rules. Consider the intermission break. Typically, while problems are implied, first acts end on a hopeful upbeat. Here, a dexterous and buoyant Quintet in which two angry gangs, two ardent but forbidden lovers and a sultry girlfriend sing of their conflicting aspirations plunges into a fatal knife fight. As a siren wails, the shocked survivors scramble off, leaving two corpses sprawled on the bare pavement. A deathly gong tolls over a dry xylophone trill as the dim street lighting fades to black, an urban requiem for shattered dreams that left audiences stunned. This show had attitude and ultimately would spawn Hair and other productions that challenged conventional stories and techniques. But that lay well into the future - indeed, its two great themes of immigrant assimilation and generational conflict would be treated again the very next year with gentle humor in Flower Drum Song. The best reflection of the bold concept is the original cast recording, cut three days after the opening, which bristles with scrappy energy (Sony SK 60724). Although much of the ardor remains in the 1960 soundtrack recording (Sony SK 48211), Bernstein's 1985 remake (DG 457 199) is ill-conceived as the grand opera he never wrote, howlingly miscast and ploddingly paced.

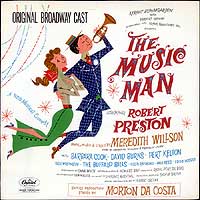

The Music Man (Meredith Willson, 1957) - Most musicals stem from the authors' imagination - Kern never set foot on a showboat nor Hammerstein in Oklahoma, Siam or the South Pacific.  Meredith Willson's tale of a con artist (winningly played by Robert Preston) redeemed by the town librarian (Barbara Cook), though, radiates authenticity, as well it should - it takes place in Mason City, Iowa where he was born and raised, boasts “76 Trombones” which evokes the great marches of John Philip Sousa in whose famous band he played flute, and neatly but respectfully pokes fun at how Americans' hearts turn to mush for their kids. Music Man's abiding glory is its extraordinary variety of vocal styles. The opening is one of the most startling ever mounted on stage - a car full of traveling salesmen deplore the challenges of their profession in an incredibly intricate four-minute a capella group rap emulating the sounds and rhythms of their moving train. There's further vocal gymnastics in the gossipy “Pick a Little, Talk a Little,” a heated argument between mother and daughter (“Piano Lesson”), revivalist preaching (“Trouble”), a chorale (“Iowa Stubborn”), vamping (“Marion the Librarian”), square dance calling (“Shipoopi”) and loads of barbershop harmony by the Buffalo Bills quartet. And there are even gorgeous ballads as well, including “Goodnight My Someone,” “My White Knight” and “Till There Was You,” admired and covered by the Beatles. (CD: Angel 64663.) Meredith Willson's tale of a con artist (winningly played by Robert Preston) redeemed by the town librarian (Barbara Cook), though, radiates authenticity, as well it should - it takes place in Mason City, Iowa where he was born and raised, boasts “76 Trombones” which evokes the great marches of John Philip Sousa in whose famous band he played flute, and neatly but respectfully pokes fun at how Americans' hearts turn to mush for their kids. Music Man's abiding glory is its extraordinary variety of vocal styles. The opening is one of the most startling ever mounted on stage - a car full of traveling salesmen deplore the challenges of their profession in an incredibly intricate four-minute a capella group rap emulating the sounds and rhythms of their moving train. There's further vocal gymnastics in the gossipy “Pick a Little, Talk a Little,” a heated argument between mother and daughter (“Piano Lesson”), revivalist preaching (“Trouble”), a chorale (“Iowa Stubborn”), vamping (“Marion the Librarian”), square dance calling (“Shipoopi”) and loads of barbershop harmony by the Buffalo Bills quartet. And there are even gorgeous ballads as well, including “Goodnight My Someone,” “My White Knight” and “Till There Was You,” admired and covered by the Beatles. (CD: Angel 64663.)

No Strings (Richard Rodgers, 1962) - Amid Broadway's usual lavish spectacle, this show presents a more modest but effective scale,  depicting the freedoms and pressures of living abroad, through an unworkable interracial romance between two Americans in Paris - a fashion model (Diahann Carroll) and a wealthy author (Richard Kiley). The atmosphere is literally lightened as the cast moves around bits of suggestive scenery and by a wonderfully breezy and sassy score. In keeping with the title, instrumentation consists only of winds, brass and percussion (and one bass) and to enhance the intimacy the players wander on stage and interact with the singers. If this concept suggests a symbolic integration of music and text, it should - following the death of Oscar Hammerstein II, his long-time lyricist whose illustrious career stretched from Show Boat to The Sound of Music, Rodgers wrote No Strings entirely by himself. (CD: Angel 64694.) depicting the freedoms and pressures of living abroad, through an unworkable interracial romance between two Americans in Paris - a fashion model (Diahann Carroll) and a wealthy author (Richard Kiley). The atmosphere is literally lightened as the cast moves around bits of suggestive scenery and by a wonderfully breezy and sassy score. In keeping with the title, instrumentation consists only of winds, brass and percussion (and one bass) and to enhance the intimacy the players wander on stage and interact with the singers. If this concept suggests a symbolic integration of music and text, it should - following the death of Oscar Hammerstein II, his long-time lyricist whose illustrious career stretched from Show Boat to The Sound of Music, Rodgers wrote No Strings entirely by himself. (CD: Angel 64694.)

Hello, Dolly (Jerry Herman, 1964) - This is my favorite example of the star vehicle, for which fans clamor to see a legend in action as much as the show itself.  Here, the attraction was Carol Channing, whose voice is, well, an acquired taste. Her every syllable gushes personality, whether she's brashly taking charge of a wildly confused situation, guiding a frightened teenager through his first romance or slyly ingratiating herself into a wealthy dowager's heart and wallet. To showcase the star, there are plenty of production numbers - “Put on Your Sunday Clothes,” “Dancing,” “Before the Parade Passes By” and the hugely popular title tune, which was a smash New-Orleans flavored hit for Louis Armstrong. Yet, Herman's fine score balances these stirring pieces with the breathtakingly intimate “Ribbons Down My Back”. Although succeeded during its long run by Pearl Bailey, Ethel Merman and Phyllis Diller (and by Barbra Streisand in the movie), the show forever remains Carol Channing's. (CD: RCA 3814.) Another prime example of this genre is Irving Berlin's 1946 Annie Get Your Gun with Ethel Merman, which boasts “There's No Business Like Show Business” and “Everything You Can Do I Can Do Better,” one of the few comic songs that's genuinely funny. (CD: MCA 3814.) Here, the attraction was Carol Channing, whose voice is, well, an acquired taste. Her every syllable gushes personality, whether she's brashly taking charge of a wildly confused situation, guiding a frightened teenager through his first romance or slyly ingratiating herself into a wealthy dowager's heart and wallet. To showcase the star, there are plenty of production numbers - “Put on Your Sunday Clothes,” “Dancing,” “Before the Parade Passes By” and the hugely popular title tune, which was a smash New-Orleans flavored hit for Louis Armstrong. Yet, Herman's fine score balances these stirring pieces with the breathtakingly intimate “Ribbons Down My Back”. Although succeeded during its long run by Pearl Bailey, Ethel Merman and Phyllis Diller (and by Barbra Streisand in the movie), the show forever remains Carol Channing's. (CD: RCA 3814.) Another prime example of this genre is Irving Berlin's 1946 Annie Get Your Gun with Ethel Merman, which boasts “There's No Business Like Show Business” and “Everything You Can Do I Can Do Better,” one of the few comic songs that's genuinely funny. (CD: MCA 3814.)

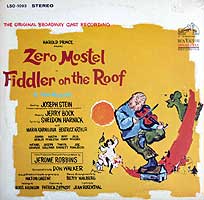

Fiddler on the Roof (Jerry Bock, Sheldon Harnick, 1964) - We're a nation of immigrants. Other ethnic shows (The Most Happy Fella, Flower Drum Song, Raisin) focused on the successful American end of the melting-pot process.  Fiddler, though, is the story of where, in a sense, we all came from - and why. Set in a small Jewish village in pre-Revolutionary Russia, it traces a milkman's desperate attempts to cope with changes that threatens his family and the only world he knows. The show's huge success and impact had as much to do with its poignant tale as the music, and so the album may seem disappointing, as several numbers contain extensive narration and make little sense extracted from the context of the plot; the two longest ones (“Tradition” and “Tveye's Dream”) are really dramas played out against musical backgrounds rather than songs as such. The moments of whimsy (“Matchmaker, Matchmaker,” “If I Were a Rich Man”) and joy (“Miracle of Miracles,” “To Life”) are offset by looming tragedy and indeed the first act ends with a pogrom and the second with expulsion and an uncertain future. “Far From the Home I Love” and the concluding “Anatevka” are acutely moving reminders of the final breakdown of the traditions that bound together the cultures of the Old World, where the promise of America and its beacon of freedom gleamed as an improbable but compelling hope that sustained our forebears. The CD album (RCA 7060) includes two tracks omitted from the LP. Fiddler, though, is the story of where, in a sense, we all came from - and why. Set in a small Jewish village in pre-Revolutionary Russia, it traces a milkman's desperate attempts to cope with changes that threatens his family and the only world he knows. The show's huge success and impact had as much to do with its poignant tale as the music, and so the album may seem disappointing, as several numbers contain extensive narration and make little sense extracted from the context of the plot; the two longest ones (“Tradition” and “Tveye's Dream”) are really dramas played out against musical backgrounds rather than songs as such. The moments of whimsy (“Matchmaker, Matchmaker,” “If I Were a Rich Man”) and joy (“Miracle of Miracles,” “To Life”) are offset by looming tragedy and indeed the first act ends with a pogrom and the second with expulsion and an uncertain future. “Far From the Home I Love” and the concluding “Anatevka” are acutely moving reminders of the final breakdown of the traditions that bound together the cultures of the Old World, where the promise of America and its beacon of freedom gleamed as an improbable but compelling hope that sustained our forebears. The CD album (RCA 7060) includes two tracks omitted from the LP.

A Chorus Line (Marvin Hamlisch / Edward Kleban, 1975) - Despite its daring concept (by Michael Bennett) and extraordinary success (15 continuous years, exceeded only by the equally non-traditional Cats), A Chorus Line to me  signals the end of the line for the great musicals. Its theme of overcoming obstacles to success is American to the core, but its bare stage and “Survivor” plot (24 hopefuls audition for eight slots in the chorus line of a new show) smack more of reality TV than the transporting fantasy stuff of which our fondest Broadway memories are made. Aside from the poignant “Nothing” and its fine novelty numbers (“I Can Do That,” “Sing” and the discretely titled “Dance: Ten; Looks: Three”), the music is largely functional - its most memorable tune (“One”) is a conscious throwback to the lavish production numbers of old and its supposed showstopper (“What I Did For Love”) is vapid pop rather than an emotionally-arresting moment. This may make for great theatre, but on record, at least (Sony SK 65282), it's just not much of a show. Besides, the great musicals are larger than life but A Chorus Line looks inward as the characters bare their souls and stir our intimate, primal fears. It's altogether too real and that's a dangerous thing to do in the arts - like explicit sex in the movies, once you show it all, what's left? Perhaps the answer lies less in the megahits that followed (Cats, Les Mis) than in the huge popularity of revivals nowadays, which just may say something about audience expectations and the undiminished ability of the great classic shows to fulfill them. signals the end of the line for the great musicals. Its theme of overcoming obstacles to success is American to the core, but its bare stage and “Survivor” plot (24 hopefuls audition for eight slots in the chorus line of a new show) smack more of reality TV than the transporting fantasy stuff of which our fondest Broadway memories are made. Aside from the poignant “Nothing” and its fine novelty numbers (“I Can Do That,” “Sing” and the discretely titled “Dance: Ten; Looks: Three”), the music is largely functional - its most memorable tune (“One”) is a conscious throwback to the lavish production numbers of old and its supposed showstopper (“What I Did For Love”) is vapid pop rather than an emotionally-arresting moment. This may make for great theatre, but on record, at least (Sony SK 65282), it's just not much of a show. Besides, the great musicals are larger than life but A Chorus Line looks inward as the characters bare their souls and stir our intimate, primal fears. It's altogether too real and that's a dangerous thing to do in the arts - like explicit sex in the movies, once you show it all, what's left? Perhaps the answer lies less in the megahits that followed (Cats, Les Mis) than in the huge popularity of revivals nowadays, which just may say something about audience expectations and the undiminished ability of the great classic shows to fulfill them.

There's something deeply satisfying about coming full circle - Show Boat began the wondrous Golden Age of the Broadway musical with its tale of “Life Upon the Wicked Stage,” and 50 years later, A Chorus Line brought it to a close with a strikingly similar theme. Together, they bracket the great shows which fully reflected the best our artists and culture had to offer, while recording for all time the trends and outlooks of our society.

For more information, I'd recommend two books in particular. Denny Martin Flinn's exhilarating Musical! A Grand Tour (Schirmer 1997) traces the forbears back to Aristophanes and treats the modern history through sweeping analytic discussions of grand themes. Abe Laufe's Broadway's Greatest Musicals (Funk & Wagnalls 1977) is a more conventional survey with all the facts and figures - plot summaries, song lists, original casts and credits; it's a bit old, but current enough to cover all the important years.

Copyright 2000 by Peter Gutmann

|