|

Nowadays we expect our conductors (and soloists, for that matter) to be everywhere and to perform everything with equal distinction. But even by our modern cosmopolitan standards, the scope of Pierre Monteux’s career and recorded legacy was extraordinary.

From the Folies Bergère to Papa Pierre

Born in 1875, Monteux was trained in the traditions of the nineteenth century, and not just the cultural summit – as a teen he played a two-year stint at the legendary Folies Bergères burlesque house in Paris. Attracted to the avant-garde, he was recruited to conduct the famous Ballets Russes, where he prepared and led the world premieres of so many cornerstones of twentieth-century ballet – Debussy’s Afternoon of a Faun and Jeux, Stravinsky’s Petrouchka and Rite of Spring and Ravel’s Daphnis et Chloë. Monteux’s career then embraced lengthy tenures at the Metropolitan Opera, the Boston Symphony, the Amsterdam Concertgebouw and, from 1936 to 1951, the San Francisco Symphony. In between, he founded several orchestras and concert series and toured as violist in the Geloso Quartet. He devoted his final decade to guest conducting the Boston and London Symphony orchestras, among many others, and to his school for conductors which he founded in 1943.

Despite such impressive historical credentials, Monteux never quite established the reputation he deserved. One reason was that, unlike most of his contemporaries, he wasn’t a showman. Rather, Monteux prided himself on being a thoroughly professional musician – moderate rather than obsessive, dedicated without being flamboyant, graceful but never sentimental. All of his performances have a natural ease and flow.  The cutting-edge tension and deep probative insights of other interpreters simply were not part of his expressive arsenal. Instead, he could always be counted upon to produce an enthusiastic but honest rendition of any score. The absence of trendiness in his work assures its permanence. His lasting influence is further assured by his legions of pupils – instead of taking well-deserved vacations he devoted his summers to teaching, first in Paris and then in Maine. His only point of vanity was defending his black hair against insinuations that it had been dyed (notwithstanding skeptics who pointed to his huge white walrus moustache).

The cutting-edge tension and deep probative insights of other interpreters simply were not part of his expressive arsenal. Instead, he could always be counted upon to produce an enthusiastic but honest rendition of any score. The absence of trendiness in his work assures its permanence. His lasting influence is further assured by his legions of pupils – instead of taking well-deserved vacations he devoted his summers to teaching, first in Paris and then in Maine. His only point of vanity was defending his black hair against insinuations that it had been dyed (notwithstanding skeptics who pointed to his huge white walrus moustache).

Another problem that may have hindered Monteux’s fame lies in the very factor that provides his enduring strength – his versatility. With only a handful of exceptions, for every work he recorded critics have pointed to more preferred recommendations. Yet few other conductors on record – and especially those of the “Golden Age” – have led so many genres of music so well and so consistently. (Can you picture Toscanini, Furtwangler or Klemperer leading ballets?) It seems safe to say that no other conductor’s recorded legacy preserves such a wide variety of classical music in such uniformly fluent readings. Even if none is quite “the best” (whatever that might mean), none is a disappointment either. Of other conductors on record, only Leonard Bernstein’s range was so eclectic.

A further problem tends to bash Monteux’s recordings for allegedly sloppy execution. Perhaps this arose as an assumed consequence of Monteux reportedly taking little interest in them. It has also been suggested that the San Francisco Symphony, with which he made many of his recordings, simply was not a first-rate ensemble. But their occasional gaffes seem no worse than those that afflict most records made before tape editing and in any event are more than overcome by the soulful spirit that propels them. In any event, he created a San Francisco “sound” that combined luminous detail and natural, moderated flow with a slight exciting edginess that communicated a sense of humanity.

Monteux had a reputation as the most beloved of conductors. Accustomed to the constant abuse of baton dictators, musicians adored him. Only rarely did they take advantage of his endearing geniality, relaxed demeanor, gentle humor and hesitancy to demand retakes. Far more often, they played their hearts out for him. Even in later years, he roused the often staid Boston Symphony (the self-proclaimed “Aristocrat of Orchestras”) to play Tchaikovsky symphonies with a thrilling spirit and attention to detail that transcends their other records of the time, and induced the Chicago Symphony to break the shackles of discipline imposed by Fritz Reiner to produce a reading of the Franck Symphony in D Minor that seethes with atmospheric depth.

Musicians weren’t the only ones who adored Monteux.  As recounted by Herb Caen in Don’t Call it Frisco, “Papa Pierre” was a fixture in his adopted home town:

As recounted by Herb Caen in Don’t Call it Frisco, “Papa Pierre” was a fixture in his adopted home town:

Short and roly-poly, with apple-red cheeks, a constant Gallic glint in his eyes and an endearing French accent, he filled the popular concept of the symphony maestro to perfection. People who never in their lives attended a concert beamed with proprietary pride as they watched him walking his beloved poodle Fifi along the streets of Nob Hill. “Fifi zay ‘allo to za nize pippils,” he’d say, picking up the tiny dog and holding her over his head. And the cable car gripman would clang his gong and everybody would wave back and forth and feel happy and proud that Papa Monteux, the big-league conductor, the Joe DeMaggio of his particular field, was “their” maestro.Joseph Wechsburg summed it up well: “People love Monteux because instinctively they feel that he is a real human being.” Musicians felt it, too: “No one has ever seen Monteux break a baton or conduct with his eyes closed.” Monteux was deeply proud of that reputation and never let fame go to his head. Caen relates that when a brigade of fireboats rushed across San Francisco Bay to meet Monteux's ferry and began to spout water in salute, he became alarmed that his boat was on fire, as it never occurred to him that they might be honoring him. Nor did he concern himself with the world beyond music. André Previn recalls that in 1950 he visited Monteux in his army uniform and announced that he was being posted to Japan, but Monteux advised against it, as he had heard that the Tokyo orchestra wasn’t very good.

Early Recordings

Monteux drew upon his variegated career to produce a discography of extraordinary scope and consistent quality. His recorded legacy began in 1929 with a set of Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring with a “Grande Orchestre Symphonique” that, despite virtually identical timings and the same orchestra, ironically is far more authentic than the composer’s own contemporaneous set – by then, Stravinsky had passed through his neoclassical phase and no longer had the temperament and artistic outlook of the brash lion who had electrified the musical world two decades before, and so it is Monteux's recording, despite rotten sound, that provides the clearest window to one of the turning points of our culture.

Equally authentic was Monteux’s next major recording – the Berlioz Symphonie Fantastique with the Paris Symphony Orchestra in 1931.  Recognizing the Symphonie’s importance as a foundation in the development of instrumental music and the art of orchestration, many attempts have been made to recreate its original sound, but Monteux’s version trumps them all for authenticity. Early in his career Monteux served as first violist and then assistant conductor of the Colonne Orchestra whose leader, Edouard Colonne, had known Berlioz and had absorbed the composer’s interpretive outlook first-hand. Indeed, as the basis of his recording Monteux used a score annotated with Colonne’s directions. (The precious score was lost when Nazis looted Monteux’s Paris home.) Thus, Monteux’s earliest recording of this seminal work is the closest sonic link we will ever have to its creator.

Recognizing the Symphonie’s importance as a foundation in the development of instrumental music and the art of orchestration, many attempts have been made to recreate its original sound, but Monteux’s version trumps them all for authenticity. Early in his career Monteux served as first violist and then assistant conductor of the Colonne Orchestra whose leader, Edouard Colonne, had known Berlioz and had absorbed the composer’s interpretive outlook first-hand. Indeed, as the basis of his recording Monteux used a score annotated with Colonne’s directions. (The precious score was lost when Nazis looted Monteux’s Paris home.) Thus, Monteux’s earliest recording of this seminal work is the closest sonic link we will ever have to its creator.

Monteux’s other early recordings, all with the Paris Symphony, accompanied the young violin sensation Yehudi Menuhin with great flexibility. A 1932 HMV Bach Concerto for Two Violins is notable more for the empathetic interplay between the soloists (Menuhin and his teacher/mentor George Enesco) than the orchestral accompaniment, which is suitably modest and free of romantic hyperbole. A 1934 HMV Paganini Concerto # 1, on the other hand, gives full rein to Menuhin’s heartfelt emotion while avoiding any hint of vulgarity. A spurious Adelaide Concerto (presented as a youthful work of Mozart, but in fact written around 1930 by Marius Casadesus) is played with vigor that challenges the delicate image attributed to its supposed composer by most musicologists of the time.

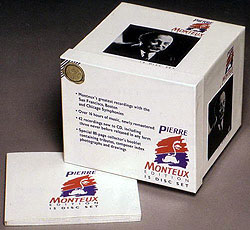

The Pierre Monteux Edition

The 1994 Pierre Monteux Edition comprises most of the works he recorded while an exclusive RCA Victor artist from 1941 to 1961, mostly with the San Francisco Symphony. It seems ironic that while he was pushed into recording French music, Monteux’s own preference was for the German repertoire. In addition to expectedly strong renditions of French works, the Monteux Edition provides wonderful readings of the Germans and Russians. The Edition is formatted as a cube with each volume in a separate standard jewel case (and the Tchaikovsky symphonies in a double slimline case), plus an 80-page trilingual booklet of appreciations and a biography.

comprises most of the works he recorded while an exclusive RCA Victor artist from 1941 to 1961, mostly with the San Francisco Symphony. It seems ironic that while he was pushed into recording French music, Monteux’s own preference was for the German repertoire. In addition to expectedly strong renditions of French works, the Monteux Edition provides wonderful readings of the Germans and Russians. The Edition is formatted as a cube with each volume in a separate standard jewel case (and the Tchaikovsky symphonies in a double slimline case), plus an 80-page trilingual booklet of appreciations and a biography.

Among the few commercially-released omissions from this segment of Monteux’s career, the most prominent is Schumann’s Symphony # 4 in D minor (1952) which boasts invigorating integration of classical restraint and romantic impulse within a fundamentally fleet (26 minutes, including the first-movement repeat) but by no means rushed impression. Also missing are Monteux’s only recording of Milhaud (the Suite symphonique # 2 [Protée]), the Brahms Alto Rhapsody with Marian Anderson, the Bruch Violin Concerto with Menuhin and no-nonsense but beautifully-sculpted Mozart Piano Concertos (#s 12 and 18, with Lili Kraus and the Boston Symphony). (The 1945 splashy, pop-infused Gruenberg Violin Concerto with Jascha Heifetz (who commissioned the work), also omitted, is in the RCA Heifetz Edition.) But regrets aside, the discs are well-filled with mostly wonderful performances:

- Bach – We tend to sneer nowadays at the Passacaglia and Fugue in C Minor in the lush Respighi orchestration (recorded with the San Francisco Symphony Orchestra in 1949) as a desecration, but Bach arrangements were common practice in earlier times (even Toscanini, that alleged purist, programmed them) and they introduced Bach to far more concert-goers and into far more homes than the originals ever did.

- Beethoven – The Symphony # 4 (SF, 1952)

boasts fine balance between the dramatic and lyric elements and is more spontaneous than the London Symphony stereo remake; the Symphony # 8 (SF, 1950) is free of rhetoric, brisk but never forced, and reflective of its classical roots.

boasts fine balance between the dramatic and lyric elements and is more spontaneous than the London Symphony stereo remake; the Symphony # 8 (SF, 1950) is free of rhetoric, brisk but never forced, and reflective of its classical roots. - Brahms reportedly told Monteux that Germans played his music too heavily while the French played it properly. The Song of Destiny (with the Stanford University Chorus, SF, 1949) emerges with fine poise between incisive drama and wistful regret. The Symphony # 2 (the only Brahms symphony he recorded – four times! – here SF, 1951) is moderately paced and resists rushing the finale.

- Liszt – Les Preludes (Boston, 1952) is free of bombast yet sharp and luminous, letting the inherent drama shine within a context of lyricism.

- Mahler – Monteux professed to not like Mahler, neither personally (Mahler reportedly snubbed him after he had prepared the chorus for a performance of the “Resurrection” Symphony) nor as a composer, but he undertook Kindertotenlieder (SF, 1950), his only Mahler recording, out of admiration for soprano Marian Anderson, whose lovely but rather fluttery voice is contrasted with carefully shaded accompaniment, somewhat more active than the mournful norm.

- Debussy – Monteux had worked intensively with Debussy to prepare performances of then-new works, and he leads them with natural ease and elegance, melding power and grace. The Images (SF, 1951) have a slightly rough edge and emergent surges of detail, while La Mer and the Nocturnes (both Boston, 1954-5) are sensual and refined.

- His Ravel, too, is elegant; ironically, La Valse (SF, 1941) is sonically superior to the later Valses Nobles et Sentimentales and Daphnis et Chloë Suite # 1 (both SF, 1946). Indeed, the artistic excellence of Monteux’s pioneering 1946 set of the Suite # 1 (as opposed to the far more popular Suite # 2) is compromised by shrill tone that turns the winds into slide-whistles and drastic compression that destroys any hint of the score’s subtleties.

- Franck – The Pièce Heroique (orchestrated by Charles O’Connell; SF, 1941) is atmospheric and tasteful,

with a fine sense of patient momentum. From its first release the Symphony in D Minor (Chicago, 1961) was hailed as nigh-definitive, which seems unfair to its other many superb recordings (including Monteux’s own bolder, more impulsive one – SF, 1950), but it indeed is brilliant, with remarkably varied textures and just enough mysticism without wallowing in excess.

with a fine sense of patient momentum. From its first release the Symphony in D Minor (Chicago, 1961) was hailed as nigh-definitive, which seems unfair to its other many superb recordings (including Monteux’s own bolder, more impulsive one – SF, 1950), but it indeed is brilliant, with remarkably varied textures and just enough mysticism without wallowing in excess. - Chausson – Monteux’s reading of the sadly neglected Symphony in B-Flat (SF, 1950) is deeply committed, ardent and sensual without a hint of vulgarity. In the Poeme de l’amour et de la mer (SF, 1952) Gladys Swarthouse’s voice overwhelms the subtleties of the symphonic texture and overrides the delicate interweaving of instrumental and vocal lines.

- Stravinsky – Beyond leading the world premieres of Stravinsky's two most popular ballet scores, Monteux went on to introduce them to the world’s concert halls. Harking back to his professional roots, his objective interpretations remained fairly constant, even sticking with the original versions rather than the composer’s revisions. The Rite of Spring (SF, 1951) may seem a bit under-nourished (although Stravinsky admired Monteux’s execution as “clean and finished” rather than taking unwanted liberties) yet the somewhat husky San Francisco sound and steadfast drive seem entirely apt, as does the finer polish and vitality of the 1959 Boston recording of the more slender Petroushka.

- Delibes – The Boston Symphony’s reduced forces (1951) emulate the pit orchestra of a ballet. The only other ballets Monteux recorded, the suites from Coppelia and Sylvia would seem to have little in common with Stravinsky, but Monteux’s ballet experience led him to never lose sight of preserving a danceable pulse, albeit leavened with sparkle and uplifting detail.

- Tchaikovsky – Generally smooth and unsentimental, but by no means dull, Monteux prompts breathtakingly fine playing that obviates the need for extrinsic stimulation to effectively communicate the inherent excitement of the final three Tchaikovsky symphonies (Boston, 1959, 1958, 1955), although the fidelity of the Sixth is a bit crude compared to the others.

- Rimsky-Korsakoff – Here, too,

Monteux presents the intensely colorful scoring and resists the temptation to underline and emote all over the gorgeous score of Scheherazade (with Naoum Blinder, violin, SF, 1942), which glows with a natural radiance. The recording is far superior to the compressed, overloaded, rumbly sound of Sadko (SF, 1945 – its first recording) and Antar (SF, 1946).

Monteux presents the intensely colorful scoring and resists the temptation to underline and emote all over the gorgeous score of Scheherazade (with Naoum Blinder, violin, SF, 1942), which glows with a natural radiance. The recording is far superior to the compressed, overloaded, rumbly sound of Sadko (SF, 1945 – its first recording) and Antar (SF, 1946). - D’Indy – Monteux championed d’Indy; his 78 sets of Istar (SF, 1945), teasingly structured so that the theme emerges only after being hinted through numerous variations, the sprawling, lush, folk-infused Symphony # 2 (SF, 1942) and the charming Symphony on a French Mountain Air (with Maxim Schapiro, piano, SF, 1941) were their first and, for quite a long time, only recordings and remain classics.

- Berlioz – The Benvenuto Cellini Overture (SF, 1952) conveys the natural ebb and flow of music and ideas. The Symphonie Fantastique (SF, 1945) is somewhat compromised by a coarse recording and some tentative ensemble, but Monteux’s acclaimed characterful approach still comes across effectively enough. Bracing Trojan and Rakoczy Marches (SF, 1945, 1951) are welcome fillers.

- Scriabin – Often whipped into a super-heated frenzy, the Poem of Ecstasy (Boston, 1952) benefits from Monteux’s sober but eminently musical approach.

- Strauss – Ein Heldenleben (with Naoum Blinder, violin, SF, 1947) sees its first release in this Edition, with well-detailed sound and an earnest effort to tame the score’s bombast and blatant sentiment. At age 84, Monteux returned to the San Francisco Symphony in 1960 for a pair of recordings – a gorgeous Wagner Siegfried Idyll (unfortunately not included here) and a superbly potent but musically sane Strauss Death and Transfiguration, presenting all the score’s inherent drama, but perhaps more notable for splendidly rich and detailed sonic fidelity that one cannot help but wish RCA had lavished on all his prior San Francisco recordings.

- Also noted – The original ten-CD release of the Monteux Edition also includes Beethoven’s Ruins of Athens Overture (SF, 1949), Ravel’s Alborado del gracioso (SF, 1947), Lalo’s La roi d’Ys Overture (SF, 1942), Ibert’s Escales (SF, 1946), d’Indy’s Fervaal Prelude (SF, 1945), Gounod’s Faust Ballet Music (previously unreleased; SF, 1947) Saint-Saens’s Havanaise (with Leonid Kogan; Boston, 1948), Debussy’s Sarabande (orchestrated by Ravel; SF, 1946) and the Fete-polonaise from Chabrier’s Le roi malgré lui (SF, 1947).

San Francisco Broadcast Concerts

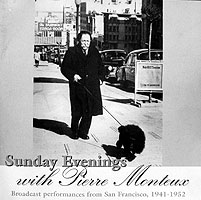

A crucial adjunct to the Monteux Edition is Sunday Evenings with Pierre Monteux, a 1997 Music and Arts set (originally 10 CDs but later expanded to 13) which focuses on San Francisco radio concerts in which Monteux presented a considerable part of his repertoire that didn’t interest the record producers (that is, nearly all but the French and Russian pieces). But there was a catch – accorded the precious prime-time Sunday evening slot, the sponsor, Standard Oil, imposed an arbitrary but rigid 23-minute limit on any piece. While a few serious works could pass that muster, symphonies and concertos often were reduced to excerpts; the tightly-integrated Beethoven Fifth suffered the ultimate indignity of being divided over two nights nearly four years apart! Consequently, a disproportionate share of the works presented were overtures, suites and tone poems. As a general matter, the concert renditions project an enthusiasm and exuberance that, like most conductors, Monteux tempered in the studio, while preserving much of his trademark elegance. Despite variable, mostly thin sound, the essential Monteux spirit consistently comes through loud and clear.

a 1997 Music and Arts set (originally 10 CDs but later expanded to 13) which focuses on San Francisco radio concerts in which Monteux presented a considerable part of his repertoire that didn’t interest the record producers (that is, nearly all but the French and Russian pieces). But there was a catch – accorded the precious prime-time Sunday evening slot, the sponsor, Standard Oil, imposed an arbitrary but rigid 23-minute limit on any piece. While a few serious works could pass that muster, symphonies and concertos often were reduced to excerpts; the tightly-integrated Beethoven Fifth suffered the ultimate indignity of being divided over two nights nearly four years apart! Consequently, a disproportionate share of the works presented were overtures, suites and tone poems. As a general matter, the concert renditions project an enthusiasm and exuberance that, like most conductors, Monteux tempered in the studio, while preserving much of his trademark elegance. Despite variable, mostly thin sound, the essential Monteux spirit consistently comes through loud and clear.

Among the many highlights:

- Beethoven – The stunner here is the manic pace and urgent insistence of the first movement of the Fifth Symphony which, after a tentative start, rushes forward to clock in at 6:29 including the exposition repeat – quite possibly the fastest on record. More than any other part of the entire collection, it serves as an extreme example to underline the difference between live impulse and studio reserve. Even so, the rest (from another concert) is comparatively conventional, if scrappily played. Perhaps as a symbol of the overall fascination and spontaneity of this set, the timpanist leaps ahead of the second chord of the otherwise stolid Consecration of the House Overture. Egmont, Fidelio and Leonore 3 Overtures are energetic yet sensible.

- Mozart and Haydn – It seems a shame that Monteux didn’t record more from the classical era. The Mozart “Haffner” Symphony and Haydn Symphony # 88 both benefit from brisk readings with sufficient flexibility and light textures to compellingly convey their lyrical essence within a context of respect for the ethos of their era. Alas, presumably due to the time restriction, only the Andante and finale were given of the Mozart Piano Concerto # 12 in A, in which Monteux fashions an ideal complement to William Kappell’s finely-chiselled solos. Overtures to Mozart’s Don Giovanni, Magic Flute and Seraglio (as well as Gluck’s Iphigenie en Aulide) are aptly reserved.

- Strauss – While the world isn’t in desperate need of yet another version of the triumvirate of Strauss favorites,

Monteux provides superb renditions of Till Eulenspiegel, Don Juan and Death and Transfiguration that intensify their variegated moods without disrupting their musical integrity, with deeply expressive solos and potent orchestral contributions, abetted by especially rich sonics, that managed to rekindle, if only briefly, my enthusiasm for these time-worn pieces. A Rosenkavalier Suite is pleasant enough, even if played with less enthusiasm and more dimly recorded.

Monteux provides superb renditions of Till Eulenspiegel, Don Juan and Death and Transfiguration that intensify their variegated moods without disrupting their musical integrity, with deeply expressive solos and potent orchestral contributions, abetted by especially rich sonics, that managed to rekindle, if only briefly, my enthusiasm for these time-worn pieces. A Rosenkavalier Suite is pleasant enough, even if played with less enthusiasm and more dimly recorded. - Wagner – One is tempted to say the same about nearly two hours of Wagner “bleeding chunks” which comprise the largest segment of the collection. (Confession: never having fully grasped the brilliance of the full operas, I’m fine with orchestral excerpts.) Perhaps the key to Monteux’s approach lies in the Meistersinger Prelude, in which he unabashedly leans into the emotional impact of each section with a constant variation of tempo and adjustment of texture. If his Parsifal Prelude, Rhine Journey and Wotan’s Farewell seem a bit dutiful, the Flying Dutchman Overture is charged by stark timpani, the Tristan Prelude and Leibestod is thrillingly ardent and the Rienzi Overture packs a potent punch.

- Liszt – Les Préludes affords a rare opportunity to compare nearly contemporaneous Monteux accounts by the Boston and San Francisco orchestras. Perhaps in part due to being a concert rendition, the 1950 San Francisco version here (the 1952 Boston is in the Edition) is freer and more heavily accented, while the recording boasts flow and smoothness (and superior sound, with richer bass and a glossier blend). A Hungarian Rhapsody # 2 seems a bit mild, if only by comparison.

- Berlioz – Perhaps the most exhilarating disc provides 75 minutes of Berlioz, surely one of Monteux’s favorite composers – he recorded five Symphonie Fantastiques, more than any other work – and clearly one with whom he deeply connected. His Roman Carnival and Corsair Overtures are predictably festive, the Trojans Prelude serious without lapsing into severity, Enfance de Christ excerpts tender but never precious, and Romeo and Juliet excerpts bursting with life and fervent love, in sharp contrast to the comparable portions of his complete Romeo (Westminster, 1962) where muted accents admittedly seem more appropriate to integrating the entire 95-minute oratorio (and his mellowing may have reflected the natural effect of age – although he had just become the London Symphony’s permanent conductor, he was 87).

- Mendelssohn – Monteux managed to slip the full “Italian” Symphony past the sponsor’s time restriction, but not by much – 25 ½ minutes – although, ironically, without the first-movement repeat, which he takes, it would have just met the limit at 23. Yet the first movement is led at break-neck speed with which the players couldn’t keep up, resulting in blurred and messy ensemble, while the rest is more moderate, if only by comparison. Hebrides and Ruy Blas Overtures are compellingly powerful, emphasizing muscular command over grace.

- Rachmaninoff – Apparently having fallen victim to the time limit,

only the middle movements of the gorgeous but sprawling Symphony # 2 were given, with their order reversed so as to end with the upbeat scherzo – although the adagio is rather stolid.

only the middle movements of the gorgeous but sprawling Symphony # 2 were given, with their order reversed so as to end with the upbeat scherzo – although the adagio is rather stolid. - Brahms – Brahms reportedly was Monteux’s favorite composer (along with Beethoven and Wagner), but, aside from the Second Symphony, his recordings of Brahms are scant – a shame, since concerts (as on a superb Tahra set of Concertgebouw Symphonies 1 and 3 and the Violin Concerto with Nathan Milstein) document wonderfully empathetic readings. According to the liner notes to the Sunday Evenings set by Arthur Bloomfield, Monteux programmed isolated movements from the symphonies in his broadcasts, but only an intensely-felt Andante sostenuto of the Symphony # 1 is included here, along with a less distinctive Tragic Overture (and five Op. 39 piano waltzes nicely orchestrated by Alfred Hertz, a suitable historical touch – in 1925 he had led the San Francisco Symphony’s first recordings and broadcasts).

- Franck – Fittingly, the original 10-CD set ends with a full disc of Franck, with whose music Monteux was especially associated. Monteux's rendition of Pierné’s arrangement of the Prelude, Chorale and Fugue is far more deeply impassioned than would ever be heard in the organ original, and Psyché excerpts and Rédemption boast acutely varied tempos without disrupting the continuity. Bloomfield speculates that the producers gave Monteux a birthday present to enable him to present intact the entire 36-minute Symphony in D Minor, the only grand-scale work to have been so permitted. A fine adjunct to his famous 1961 Chicago studio LP (included in the Edition), the 1946 concert is far more spontaneous and boasts a full two minute-faster first movement, but the visceral impact is somewhat compromised by flat sonics.

- Miscellany – While not as atmospheric as Stokowski’s London Symphony version, Messaien's L’Ascension is notable for its inclusion here if only because it’s the only “modern” work in the entire set (or, for that matter, which Monteux otherwise recorded). Also notable: an uncommonly dynamic Sibelius Valse Triste, a playful Rossini Italiana in Algeri Overture, an agile Thomas Mignon Overture, an exquisitely nuanced Weber Euryanthe Overture, a sparkling (albeit abridged) Rimsky-Korsakoff Russian Easter Overture, vigorous Borodin Polovetsian Dances, and a suitably extroverted Sousa Stars and Stripes Forever March.

2006 Expanded Version – In 2006 Music and Arts released a remastered and expanded version of Sunday Evenings with Pierre Monteux with a slightly modified cover design that included three more CDs from Sunday evening San Francisco Symphony broadcast concerts.

- CD 11 is a grab-bag that exemplifies Monteux’s versatility, spanning the 18th to the 20th centuries and comprising a tour of France, Germany, Spain and Italy. Nicolai’s Merry Wives of Windsor Overture emerges as bracing and Massenet’s Phedre as utterly convincing; Falla’s Three-Cornered Hat Suite struts with atmosphere, the disparate segments of Rossini’s William Tell Overture are fully characterized yet flow together beautifully and Wagner’s Tannhauser Overture is uncommonly light and propulsive.

All are sandwiched between Gretry’s ballet music from Cephale et Procris and Respighi’s Fountains of Rome, both of which strike me more as background or movie soundtrack music than concert-hall material but here manage to sound absorbing – and perhaps that’s the true test of a great conductor, whose talent and inspiration can infuse the mediocre with more than a hint of substance.

All are sandwiched between Gretry’s ballet music from Cephale et Procris and Respighi’s Fountains of Rome, both of which strike me more as background or movie soundtrack music than concert-hall material but here manage to sound absorbing – and perhaps that’s the true test of a great conductor, whose talent and inspiration can infuse the mediocre with more than a hint of substance. - CD 12 seems the most disposable, presenting the first movements of three concertos in rather middling performances. Solomon had been playing the Beethoven Third in concert since age 9 and had recorded it for EMI both in 1944 with Boult and the BBC and, more leisurely, in 1956 with Menges and the Philharmonia. While fundamentally his same light, precise interpretation (including Clara Schumann’s unassuming cadenza), Monteux in 1951 provides a more vibrant accompaniment that prompts somewhat greater flexibility in the solos, although they are blurred by an especially dull recording. Shura Cherkassky’s 1944 Tchaikovsky First is more robust (and less individual) than his extraordinarily lush, free-wheeling 1951 DG recording with Ludwig and the Berlin Philharmonic, and is further compromised by annoying rumble that easily could have been filtered. The 1947 Brahms Double emerges as rather schizoid – the solos by long-time concertmaster Naoum Blinder and his younger brother Boris are as deeply felt as their relationship would suggest, and are offset by far crisper and quicker orchestral segments. It’s a shame they omitted the ensuing Andante, where their contributions would have melded, or the finale, where the contrast might have seemed more appropriate. The disc is filled out with Lili Kraus, who affectionately caresses the solo passages that remain in Liszt’s rather superfluous orchestration of Schubert’s Wanderer Fantasy.

- CD 13, like CD 11, begins and ends with pleasant, upbeat fluff – the polka, tango, passadoble and tarantella from Walton’s first Façade Suite and Chadwick’s Jubilee. It also contains the sole vocal work in the entire collection, a brief song with Dorothy Warenskjold: “Risurrezione: Dio pietoso” that evokes a leftover from Turandot with good reason – it’s by Franco Alfano, who completed that opera after Puccini’s death. While well-characterized, Sibelius’s Pohjola’s Daughter curiously ends at the final climax rather than continuing through the remaining minute or so of tender deceleration. The prize here, and indeed of the entire set, is the Schumann Symphony # 4, given a month before the RCA studio recording and clocking in several minutes faster – barely 22, perhaps in part to placate the sponsor’s arbitrary limitation. Viscerally thrilling and bristling with energy, it smoothly integrates the sections of vigor and repose; the pace, while fleet, never seems rushed. Atypically, though, the balance is skewed with overly prominent brass that provides an added ominous sense to the fourth-movement transition but obscures much of the first-movement melody. The Mozart “Jupiter” Symphony emerges as a soul-mate with the Schumann, taken briskly with an especially swift first movement but then calming down for the rest, reminiscent of the electrifying 1927 Coates 78s.

Although beyond the scope of this article, we should briefly note Monteux’s final set of warm yet vibrant studio recordings,

made in his late ‘eighties with the London Symphony and Vienna Philharmonic for Decca/London (but mostly released in the US on RCA). Among these are the Dvorak Seventh Symphony, Haydn’s “Surprise” and ”Clock” Symphonies, the complete Ravel Daphnis et Chloë, Elgar’s Enigma Variations, the Sibelius Symphony # 2, the Brahms Violin Concerto with Henryk Szeryng, Tchaikovsky Sleeping Beauty excerpts, remakes of Scheherazade and the Brahms Symphony # 2 and the first eight Beethoven symphonies (the Ninth was released on Westminster). With the exception of a sadly lame remake of The Rite of Spring with the Paris Conservatoire Orchestra, all boast steadfast playing, fine balance and credible sound that eschews others’ urgent drama and deep philosophical exploration to simply revel in the pleasure of unadorned great music. We should also note the three complete operas Monteux recorded in the mid-1950s (Gluck’s Orfeo and Verdi’s La Traviata with the Rome Opera and, more in his element, a highly-acclaimed Massenet Manon with Victoria de los Angeles, Henri Legay, Michel Dens and the Opera Comique), together with a significant number of posthumously-issued Monteux concerts, including many on various labels with the Amsterdam Concertgebouw, with which he was closely associated both before and after World War II. Like the Sunday Evenings set, all serve to enlarge our appreciation of his remarkable range and consistent excellence.

made in his late ‘eighties with the London Symphony and Vienna Philharmonic for Decca/London (but mostly released in the US on RCA). Among these are the Dvorak Seventh Symphony, Haydn’s “Surprise” and ”Clock” Symphonies, the complete Ravel Daphnis et Chloë, Elgar’s Enigma Variations, the Sibelius Symphony # 2, the Brahms Violin Concerto with Henryk Szeryng, Tchaikovsky Sleeping Beauty excerpts, remakes of Scheherazade and the Brahms Symphony # 2 and the first eight Beethoven symphonies (the Ninth was released on Westminster). With the exception of a sadly lame remake of The Rite of Spring with the Paris Conservatoire Orchestra, all boast steadfast playing, fine balance and credible sound that eschews others’ urgent drama and deep philosophical exploration to simply revel in the pleasure of unadorned great music. We should also note the three complete operas Monteux recorded in the mid-1950s (Gluck’s Orfeo and Verdi’s La Traviata with the Rome Opera and, more in his element, a highly-acclaimed Massenet Manon with Victoria de los Angeles, Henri Legay, Michel Dens and the Opera Comique), together with a significant number of posthumously-issued Monteux concerts, including many on various labels with the Amsterdam Concertgebouw, with which he was closely associated both before and after World War II. Like the Sunday Evenings set, all serve to enlarge our appreciation of his remarkable range and consistent excellence.

Specific recommendations? Unnecessary. Simply follow your taste. Since this is Monteux, you won’t be disappointed.

![]()

Copyright 2017 by Peter Gutmann

copyright © 1998-2017 by Peter Gutmann. All rights reserved.