|

You know those ancient legends where people  fervently wish for something, and then up pops a genie and they wind up with far more than they can handle? fervently wish for something, and then up pops a genie and they wind up with far more than they can handle?

I once lamented that while we had fine historical CD surveys of the violin, cello, viola and even the harpsichord, sorely missing was the most popular instrument of all, the piano. Well, a genie at Philips must have heard my call.  I was soon reveling in their massive "Great Pianists of the 20th Century" edition. Would you believe two hundred discs? And you thought Bear Family boxes were huge? I was soon reveling in their massive "Great Pianists of the 20th Century" edition. Would you believe two hundred discs? And you thought Bear Family boxes were huge?

Fortunately, the Edition isn't as unwieldy as it might sound. It comes in 100 mid-priced 2-CD units, each devoted to a single artist. Sheer size apart, this is a hugely impressive project. Here's the stats: 72 pianists, of whom seven giants (Arrau, Brendel, Gilels, Horowitz, Kempff, Richter and Rubinstein) are honored with three volumes each; sixteen more artists get two. (OK, wise guys - the math is correct, since two of the volumes feature pairs of pianists.) The total running time is over 250 hours, with most discs very full (some approach 81 minutes!). Much of the music is new to CD. Although Philips' own material (and that of their Decca and Deutsche Grammophon affiliates) figures prominently, recordings were licensed from the other majors (EMI, RCA and Sony) and some smaller labels as well.

Any project of this scope reflects the taste of its producer, in this case life-long piano enthusiast Tom Deacon, whose credentials and culture I wouldn't dare challenge. Even so, a few overall quibbles still seem fair, as my frustrations with this edition go beyond questions of personal taste and in fact seem fueled by the Edition's own liner notes.

While the focus is on solo work, there are also lots of concertos and other works with orchestra but nothing in between, even though the notes for many sets extol their subjects' chamber music fame. For a 20th century piano survey, there's hardly any 20th century piano music, although the notes vaunt several of the artists as committed modernists. Nor are many early masters of the century (de Greef, Lamond) or the great composer-pianists (Bartok, Prokofiev) included, presumably because they were not sufficiently prolific to fill 2 CDs by themselves, even though they are praised in their students' volumes. Even within individual sets, the notes cruelly tease with unfulfilled expectations, touting several artists' preferred repertoire which is omitted from their volumes; thus, while Leon Fleisher's unique claim to the obscure but fascinating left-hand literature is duly noted, all we get of that is his overly-familiar Ravel Concerto.

Indeed, the selections all too often seem stuck in a standard repertoire rut, with huge amounts of overlap. Among major works alone over fifty receive three or more performances. Admittedly, they're mostly masterworks and make for fascinating stylistic comparisons, but some more variety would have been nice, too. Thus, we get six versions of Prokofiev's Third Concerto, but none of Beethoven's; eight of Chopin's Second Sonata but none of Brahms's; and five of Ravel's slight Sonatina but none of his more substantial Miroirs. If you're looking to assemble a comprehensive survey of great piano music, this clearly won't do.

Rather, the organizing principle was to create musical portraits of some of the most distinctive personalities of the recorded era.  To that end, the project is wildly successful – absorbing one of these volumes reveals as much of its subject as a detailed biography or analysis. Once you're willing to submit to the producers' quirks, this edition affords a wealth of fabulous pianism that combines stunning technique, profound musical understanding and brilliant interpretive insight. To that end, the project is wildly successful – absorbing one of these volumes reveals as much of its subject as a detailed biography or analysis. Once you're willing to submit to the producers' quirks, this edition affords a wealth of fabulous pianism that combines stunning technique, profound musical understanding and brilliant interpretive insight.

But where do you start? Philips has made that an easy choice. For the price of a single mid-line CD, they've packaged a hardcover book of artist bios and a piano history with a 2-CD sampler of selections from all but two of the artists (licensing problems?), graced with cogent performance notes. But don't mistake Philips's gesture for generosity. Hearing this stuff is addictive and you'll be sorely tempted to plunge into the full Edition.

The sampler will help guide you to your own favorites. Here are mine among the first fifty volumes. They're in no particular order; my current favorite invariably is the one I've heard most recently.

- Schnabel's Beethoven, Kempff's Brahms, Rubinstein's Chopin, Cortot's Schumann, Richter's Prokofiev and Laroccha's Albinez all are utterly transparent - they sublimate ego to achieve full identification with a composer's expression - and thus represent the ultimate triumph of truly great artistry.

- Along with Schnabel and Cortot, Lhevinne and Rachmaninoff were "Golden Age" pianists, whose authenticity arose from immersion in the very tradition that produced our core repertoire; while younger artists try to emulate that vision, these guys lived it.

- Rosalyn Tureck recreates Bach with rarefied feeling.

- Maria Yudina jolts often staid Bach and Beethoven variations with electrifying authority.

- Alfred Brendel presents Haydn and Schubert with sparkling clarity.

- Clifford Curzon presents Mozart and the same Schubert with exquisite sensitivity.

- Shura Cherkassky imbues Chopin with sweeping personal poetry.

- Mikhail Pletnev enlivens his Tchaikovsky with balletic elan.

- Arturo Benedetti Michelangeli colors the impressionists with radiant hues.

- John Ogden revitalizes unusual repertoire with compelling intensity.

- Lyubov Bruk and Mark Taimanov, duo-pianists, may double your pleasure.

- Byron Janis, Julius Katchen and Leon Fleisher are quintessentially American - bold and brash.

- Evgeny Kissin dazzles as a phenomenal teenage prodigy.

- Dinu Lipatti, Clara Haskil and Ingrid Haebler communicate with disarming directness.

- Ivan Moravec plays so smoothly you'll forget that his piano's a percussion instrument.

- Maurizio Pollini, Zoltan Koksis, Vladimir Ashkenazy, Alexis Weissenberg and Martha Argerich play with clean, modern splendor that defies pigeon-holing.

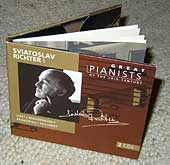

- Nothing, though, matches the inspiration of a live concert. If I had to choose just one volume as a great place to start it would be the first devoted to Sviatoslav Richter, which combines his definitive Prokofiev with a staggeringly intense 1958 Sofia recital that amply validates why many consider Richter to have been the pianist of the century. Also wondrous is an awesome 1974 concert of Bach, Chopin and flashy showpieces by Jorge Bolet.

I'm even thrilled with the packaging, a rare emotion since the demise of gatefold LPs.  In lieu of a clunky double jewelbox, each volume comes as a DigiPak, a hardback book with stiff paper CD sleeves glued to the inside covers and the notes bound in between. The DigiPak takes up the same space as a single jewelbox, but it's far more attractive and sturdy. In lieu of a clunky double jewelbox, each volume comes as a DigiPak, a hardback book with stiff paper CD sleeves glued to the inside covers and the notes bound in between. The DigiPak takes up the same space as a single jewelbox, but it's far more attractive and sturdy.

It's great to see a major label adopt a sensible alternative to the crummy jewelbox. Boy, do I hate those things! Oh, I know all the marketing rationales. Durable? Try dropping one on the floor. Attractive? Not unless you've got a plastic fetish. Compact? They're mostly wasted space, hogging three times the room needed for a CD, booklet and paper sleeve. And all the crocodile tears once shed over the longbox pale compared to the sheer environmental waste of these things, which promise to bloat landfills for generations to come.

But the DigiPaks do present a slight problem - it's nearly impossible to extract the discs from their tight sleeves without fingerprinting and scratching them; not with major globs and gouges that cause mistracking, but the type that leads clerks in used CD stores to feign agony. If you're up for an art project, you can cut out an hourglass piece from the top of the sleeve to the center hole and then guide the CD in and out with your finger - an inconvenience, perhaps, but well worth escaping the tyranny of the jewelbox. it's nearly impossible to extract the discs from their tight sleeves without fingerprinting and scratching them; not with major globs and gouges that cause mistracking, but the type that leads clerks in used CD stores to feign agony. If you're up for an art project, you can cut out an hourglass piece from the top of the sleeve to the center hole and then guide the CD in and out with your finger - an inconvenience, perhaps, but well worth escaping the tyranny of the jewelbox.

Oh, one thing more. As if 200 CDs were not enough, the producer mentioned in a Gramophone interview that he was working on another hundred volumes! Amid the abundant glories of the present edition, I won't deny that I just may have wished for that!

= = = = = = = = = = = = =

Hopefully, my overall enthusiasm for the marvels of the "Great Pianists of the 20th Century" Edition is amply evident from the foregoing column I had written concerning the first half. Once the remaining fifty volumes had been released, I updated my recommendations to cover some highlights of the rest somewhat more expansively without the constraints of print limitations. In late 2005 I went back to provide others (Backhaus, Barenboim, Bruk/Taimanov, Cliburn, Cortot, Cziffra, Francois, Friedman, Gieseking, Haskil, Katchen, Kissin, the Lhevinnes, Moiseiwitch, Moravec, Paderewski, Pletnev, Previn, Rachmaninoff, Schnabel and Uchida). The ones I've omitted are simply those for which I found I had little to say, as well as those about whom others have written extensively.

- Geza Anda (1921 - 1976) - Just call this volume Geza Anda's Greatest Hits. Anda is best remembered for one of the greatest early triumphs of crossover marketing,

in the ancient times before soundtrack albums. His ravishing 1961 rendition (at the keyboard and conducting) of the andante of Mozart's Piano Concerto # 21 in C was popularized as the theme from the 1967 Swedish romantic film Elvira Madigan, which then returned the favor when Anda's original album was reissued with a wistful cover portrait of the lead actress and became a smash hit - deservedly so, as the performance is truly exquisite, lush but with ample respect for Mozart's chamber sonority. The net result: even today, the Mozart 21st is still known as the "Elvira Madigan" Concerto. Among classical buffs, though, Anda is better remembered for his fabulous idiomatic set of the Bartok Piano Concertos with Ferenc Fricsay and the RSO Berlin. Connoisseurs further revere Anda for his deeply contemplative set of the Chopin Waltzes, waxed in his final half-year. All three performances comprise this fine edition. in the ancient times before soundtrack albums. His ravishing 1961 rendition (at the keyboard and conducting) of the andante of Mozart's Piano Concerto # 21 in C was popularized as the theme from the 1967 Swedish romantic film Elvira Madigan, which then returned the favor when Anda's original album was reissued with a wistful cover portrait of the lead actress and became a smash hit - deservedly so, as the performance is truly exquisite, lush but with ample respect for Mozart's chamber sonority. The net result: even today, the Mozart 21st is still known as the "Elvira Madigan" Concerto. Among classical buffs, though, Anda is better remembered for his fabulous idiomatic set of the Bartok Piano Concertos with Ferenc Fricsay and the RSO Berlin. Connoisseurs further revere Anda for his deeply contemplative set of the Chopin Waltzes, waxed in his final half-year. All three performances comprise this fine edition.

- Martha Argerich (b. 1941), volume 2 - Beyond exciting accounts of the Schumann Second and Liszt b minor Sonatas, the emphasis here is on Chopin,

including the complete Preludes and Third Sonata. Argerich's approach provides a clear rebuke to classical gender stereotyping: the Chopin of Anda, Cherhassky, Moravec and other guys in the Great Pianists Edition oozes soft, gentle, nurturing sensitivity - "effeminate," if you will - while Argerich's is aggressive, bold, temperamental and edgy. There's lots of beauty, but it's the type that emerges in contrast to rough, elemental power. There's also plenty of romanticism here - not the pale, wispy pining sort, but one that seems to better reflect the ardent, fevered, emotional tumult of a young, conflicted composer. This is a stunning collection. including the complete Preludes and Third Sonata. Argerich's approach provides a clear rebuke to classical gender stereotyping: the Chopin of Anda, Cherhassky, Moravec and other guys in the Great Pianists Edition oozes soft, gentle, nurturing sensitivity - "effeminate," if you will - while Argerich's is aggressive, bold, temperamental and edgy. There's lots of beauty, but it's the type that emerges in contrast to rough, elemental power. There's also plenty of romanticism here - not the pale, wispy pining sort, but one that seems to better reflect the ardent, fevered, emotional tumult of a young, conflicted composer. This is a stunning collection.

- Wilhelm Backhaus (1884 - 1969) - The notes by Piero Rattalino recall that Backhaus, whose recording career began with the first full concerto ever committed to disc (Grieg’s, in 1910),

was prized by producers of the time for his calm demeanor that achieved continuity across the required side breaks, a practical boon but one that carried an aesthetic limitation - an “expressive modesty that … borders on coldness.” Indeed, it’s hard to muster much enthusiasm for his 1952 Brahms Concerto # 2 with Schuricht and the Vienna Philharmonic, coming midway between his acclaimed 1939 and 1967 accounts with Bohm (and the Saxon State and Vienna Philharmonic Orchestras, respectively) – despite shrill sound, it’s attentive, solid and thoroughly idiomatic, yet superfluous, given the realm of other fine recordings nowadays with superior sound and/or inspiration. Fortunately, the rest of this collection is far more interesting. Five Beethoven sonatas (the “Pathetique,” “Tempest,” “Les adieux,” Op. 79 and Op. 111) present one of his foremost specialties, where a dry directness and lack of emotion seem especially apt. All are from a March 1954 concert. While it’s nice to have a supplement to his Decca stereo studio recordings of these works, they’re barely distinguishable, trading only slightly greater animation for simplified dynamics, lesser inflection, and far thinner sonics. Of several encores (all live as well), a Chopin Etude in f minor, Op. 25 # 2 and a Brahms Intermezzo in C, Op. 119 # 3 are beautifully played and organized without a hint of ostentation but with breathtakingly secure technique and the most subtle of rhythmic inflection. Alongside the Beethoven, they document a self-effacing artist with sufficient confidence to let the music speak for itself. was prized by producers of the time for his calm demeanor that achieved continuity across the required side breaks, a practical boon but one that carried an aesthetic limitation - an “expressive modesty that … borders on coldness.” Indeed, it’s hard to muster much enthusiasm for his 1952 Brahms Concerto # 2 with Schuricht and the Vienna Philharmonic, coming midway between his acclaimed 1939 and 1967 accounts with Bohm (and the Saxon State and Vienna Philharmonic Orchestras, respectively) – despite shrill sound, it’s attentive, solid and thoroughly idiomatic, yet superfluous, given the realm of other fine recordings nowadays with superior sound and/or inspiration. Fortunately, the rest of this collection is far more interesting. Five Beethoven sonatas (the “Pathetique,” “Tempest,” “Les adieux,” Op. 79 and Op. 111) present one of his foremost specialties, where a dry directness and lack of emotion seem especially apt. All are from a March 1954 concert. While it’s nice to have a supplement to his Decca stereo studio recordings of these works, they’re barely distinguishable, trading only slightly greater animation for simplified dynamics, lesser inflection, and far thinner sonics. Of several encores (all live as well), a Chopin Etude in f minor, Op. 25 # 2 and a Brahms Intermezzo in C, Op. 119 # 3 are beautifully played and organized without a hint of ostentation but with breathtakingly secure technique and the most subtle of rhythmic inflection. Alongside the Beethoven, they document a self-effacing artist with sufficient confidence to let the music speak for itself.

- Daniel Barenboim (b. 1942) - This set provides two snapshots that barely suggest the breadth of Barenboim’s career. The first is from 1971.

An entire CD is devoted to two of his collaborations with Otto Klemperer that year – the Mozart Concerto # 25 and the Beethoven Concerto # 1. True, they document the taming of a young soloist by the respected control of a wizened elder master, plus Klemperer enlivens the orchestra with prominent winds that leaven his deliberate tempi and presciently suggest the sonority of the late classical era, but one (or even a single movement) would have sufficed to make the point. Also from 1971 is his Brahms Concerto # 1 with Barbirolli leading the Philharmonia, an unusually deliberate reading that seems more ponderous rather than inspired, missing much of the profundity later mined by Zimerman and Bernstein’s similar approach. The second snapshot is the three Liszt Sonetti del Petrarca from 1980 and the Liszt arrangement of Wagner’s Isolde’s Liebestod from 1982. Here, too, a single example would have been enough and, indeed, the notes concede that the passionate Liszt is surprisingly nonchalant. Admittedly, Barenboim’s fame as a conductor (emerging as one of our preeminent Beethoven and Bruckner conductors in the footsteps of his idol Furtwangler) is beyond the scope of this Edition, but what of his wonderful chamber music in which his romantic tendencies were in full bloom, especially when partnering his wife, the great cellist Jacqueline du Pré? Or, as the pathway to his conducting career, one of the Mozart concerti which he both played and conducted from the keyboard? Snapshots can be interesting, but it’s often hard to infer from them the richness of their surroundings. An entire CD is devoted to two of his collaborations with Otto Klemperer that year – the Mozart Concerto # 25 and the Beethoven Concerto # 1. True, they document the taming of a young soloist by the respected control of a wizened elder master, plus Klemperer enlivens the orchestra with prominent winds that leaven his deliberate tempi and presciently suggest the sonority of the late classical era, but one (or even a single movement) would have sufficed to make the point. Also from 1971 is his Brahms Concerto # 1 with Barbirolli leading the Philharmonia, an unusually deliberate reading that seems more ponderous rather than inspired, missing much of the profundity later mined by Zimerman and Bernstein’s similar approach. The second snapshot is the three Liszt Sonetti del Petrarca from 1980 and the Liszt arrangement of Wagner’s Isolde’s Liebestod from 1982. Here, too, a single example would have been enough and, indeed, the notes concede that the passionate Liszt is surprisingly nonchalant. Admittedly, Barenboim’s fame as a conductor (emerging as one of our preeminent Beethoven and Bruckner conductors in the footsteps of his idol Furtwangler) is beyond the scope of this Edition, but what of his wonderful chamber music in which his romantic tendencies were in full bloom, especially when partnering his wife, the great cellist Jacqueline du Pré? Or, as the pathway to his conducting career, one of the Mozart concerti which he both played and conducted from the keyboard? Snapshots can be interesting, but it’s often hard to infer from them the richness of their surroundings.

- Jorge Bolet (1914 - 1990), Volume II - Here's another superb Liszt collection to place alongside the Horowitz, Cziffra and Ogden volumes. But even beyond its intrinsic splendor,

this set highlights the glory of the medium of recordings, which we often disparage in favor of concerts. Indeed, Bolet's own volume I is devoted to a stunning 1974 Carnegie Hall recital, the liner notes to which carp that Bolet was far happier before an audience, and suggesting that his studio work was cautious and less inspired. But that's simply not true. While concerts and records are surely different media, neither is inherently superior to the other. The edgy fireworks of a concert are indeed thrilling to experience (and indeed are fitting to keep the attention of the audience) but can tend to wear thin over repeated hearings. Great studio recordings, intended to be savored in private, can wield a more subtle but perhaps more lasting power that transcends the moment. While avoiding the the greater visceral excitement and risk-taking of a concert, Bolet's studio Liszt exerts a unique spell - confident, relaxed, finely-structured, and assertive without being overwhelming. Take, for example, the Harmonies du Soir. Richter's stunning live 1958 Sofia version (on his Volume I) builds to a shattering climax, rendered in white heat with blazing virtuosity, leaving the listener drained with exhaustion. Bolet's, though, gleams with a subtlety that could get lost in the concert hall, pulsing instead with an ebb and flow of fluid feeling, lifting you up and letting you down gently in the peace of your home. The marvel begs to be heard again as soon as it's over - a special type of magic that only recordings can conjure. this set highlights the glory of the medium of recordings, which we often disparage in favor of concerts. Indeed, Bolet's own volume I is devoted to a stunning 1974 Carnegie Hall recital, the liner notes to which carp that Bolet was far happier before an audience, and suggesting that his studio work was cautious and less inspired. But that's simply not true. While concerts and records are surely different media, neither is inherently superior to the other. The edgy fireworks of a concert are indeed thrilling to experience (and indeed are fitting to keep the attention of the audience) but can tend to wear thin over repeated hearings. Great studio recordings, intended to be savored in private, can wield a more subtle but perhaps more lasting power that transcends the moment. While avoiding the the greater visceral excitement and risk-taking of a concert, Bolet's studio Liszt exerts a unique spell - confident, relaxed, finely-structured, and assertive without being overwhelming. Take, for example, the Harmonies du Soir. Richter's stunning live 1958 Sofia version (on his Volume I) builds to a shattering climax, rendered in white heat with blazing virtuosity, leaving the listener drained with exhaustion. Bolet's, though, gleams with a subtlety that could get lost in the concert hall, pulsing instead with an ebb and flow of fluid feeling, lifting you up and letting you down gently in the peace of your home. The marvel begs to be heard again as soon as it's over - a special type of magic that only recordings can conjure.

- Lyubov Bruk (1926 - 1996) and Mark Taimanov (b. 1926) - Nope, I never heard of them either before this. Interestingly, though, it turns out that Taimanov is far more famed in chess circles,

where for many years he was ranked among the world’s top ten masters. A variation of the Sicilian opening is even named after him. (His chess career crashed in 1971 when he lost 6-0 to then-American Bobby Fischer in the world championship quarter rounds. Despite his loyalty (a picture in the booklet shows him playing chess as Che Guevara looks on), the Soviets felt so embarrassed as to strip him of his salary and travel privileges.) But it’s his musical calling that’s the focus here. In the notes he provided, Taimanov recalls beginning to play together with Bruk as 12-year old students, an association that led to marriage and continued for over 3 decades until they parted ways. He calls theirs a “unity of opposites” – she was delicate and refined, he outgoing and romantic. As heard here, though, the commonality of approach and close coordination are truly remarkable, perhaps arising from their long-time spiritual union. Aside from its technical challenges (it’s hard enough for a single brain to manage ten fingers, but far more demanding for two independent minds to coordinate 20), the use of two pianos produces not only thicker textures but the opportunity for more complexity and a heady rush of more notes than two hands can produce. Taimanov claims that most of their repertoire was recorded. Frustratingly, though, this volume omits many of the pieces he cites as particular favorites (by Saint-Saens, Schumann and Mendelssohn), as well as others, now obscure, written especially for them. All would be fascinating to hear (and seem otherwise unavailable). Of the material that is included, Taimanov and Bruk display a fine range of feeling appropriate to each work. While their background and training suggest a natural affinity for the Arensky and Rachmaninoff Suites for Two Pianos, their Mozart (the Concerto for Two Pianos, KV 365) and Busoni Duetto concertante (modeled after the finale of Mozart’s Piano Concerto in F, KV 459) are nicely animated rather than classically restrained, and the rarely-heard Chopin Rondo for Two Pianos in C, Op. 73 gives free rein to the poles of their personalities. Perhaps most fascinating and unexpected is their French repertoire, in which they capture the dry wit and abundant energy of Milhaud’s Scaramouche and Poulenc’s Concerto for Two Pianos and Sonata for Two Pianos. where for many years he was ranked among the world’s top ten masters. A variation of the Sicilian opening is even named after him. (His chess career crashed in 1971 when he lost 6-0 to then-American Bobby Fischer in the world championship quarter rounds. Despite his loyalty (a picture in the booklet shows him playing chess as Che Guevara looks on), the Soviets felt so embarrassed as to strip him of his salary and travel privileges.) But it’s his musical calling that’s the focus here. In the notes he provided, Taimanov recalls beginning to play together with Bruk as 12-year old students, an association that led to marriage and continued for over 3 decades until they parted ways. He calls theirs a “unity of opposites” – she was delicate and refined, he outgoing and romantic. As heard here, though, the commonality of approach and close coordination are truly remarkable, perhaps arising from their long-time spiritual union. Aside from its technical challenges (it’s hard enough for a single brain to manage ten fingers, but far more demanding for two independent minds to coordinate 20), the use of two pianos produces not only thicker textures but the opportunity for more complexity and a heady rush of more notes than two hands can produce. Taimanov claims that most of their repertoire was recorded. Frustratingly, though, this volume omits many of the pieces he cites as particular favorites (by Saint-Saens, Schumann and Mendelssohn), as well as others, now obscure, written especially for them. All would be fascinating to hear (and seem otherwise unavailable). Of the material that is included, Taimanov and Bruk display a fine range of feeling appropriate to each work. While their background and training suggest a natural affinity for the Arensky and Rachmaninoff Suites for Two Pianos, their Mozart (the Concerto for Two Pianos, KV 365) and Busoni Duetto concertante (modeled after the finale of Mozart’s Piano Concerto in F, KV 459) are nicely animated rather than classically restrained, and the rarely-heard Chopin Rondo for Two Pianos in C, Op. 73 gives free rein to the poles of their personalities. Perhaps most fascinating and unexpected is their French repertoire, in which they capture the dry wit and abundant energy of Milhaud’s Scaramouche and Poulenc’s Concerto for Two Pianos and Sonata for Two Pianos.

- Robert Casadesus (1899 - 1972) - The perceptive notes by Farhan Malik pinpoint the "problem" in attempting to describe Casadesus's art - you really can't.

Casadesus is perhaps best heard as a bridge between centuries and cultures. Born in 1899, he may have been the "last great pianist of the 19th century" and indeed, although allied with the French modernists, his style was of the old school - heavy rather than elegant, with lots of detail subsumed into structural attention. The first disc is devoted to Baroque (Bach, Rameau and Scarlatti), with precise articulation imbued with feeling and inflection, and early Beethoven (the Sonata # 2), gentle and light. The second disc begins by documenting one of the great duo-piano teams on record - Robert and his wife Gaby, who imbue Faure's Dolly Suite and especially Debussy's En Blanc et Noir with exquisite feeling and deep emotional coordination; it's a shame that the Six Epigraphes Antiques, its original LP companion, is omitted, despite ample CD capacity. Robert then flatters Faure solo pieces with his devoted attention. The set concludes with his 1947 Ravel Piano Concerto in D for the Left Hand with Ormandy and the Philadelphia Orchestra, which is not only deservedly famous in its own right but also rings with authority stemming from the close association between performer and composer. Casadesus is perhaps best heard as a bridge between centuries and cultures. Born in 1899, he may have been the "last great pianist of the 19th century" and indeed, although allied with the French modernists, his style was of the old school - heavy rather than elegant, with lots of detail subsumed into structural attention. The first disc is devoted to Baroque (Bach, Rameau and Scarlatti), with precise articulation imbued with feeling and inflection, and early Beethoven (the Sonata # 2), gentle and light. The second disc begins by documenting one of the great duo-piano teams on record - Robert and his wife Gaby, who imbue Faure's Dolly Suite and especially Debussy's En Blanc et Noir with exquisite feeling and deep emotional coordination; it's a shame that the Six Epigraphes Antiques, its original LP companion, is omitted, despite ample CD capacity. Robert then flatters Faure solo pieces with his devoted attention. The set concludes with his 1947 Ravel Piano Concerto in D for the Left Hand with Ormandy and the Philadelphia Orchestra, which is not only deservedly famous in its own right but also rings with authority stemming from the close association between performer and composer.

- Van Cliburn (b. 1934) - Like Casals, Paderewski and Hess, Van Cliburn will be remembered as much for politics as music. During the height of the Cold War,

the lanky young Texan ventured to Moscow where he won the first Tchaikovsky Competition and wowed Russian audiences with his open attitude and magnificent playing of “their” music. When he returned home to a ticker-tape parade and a hero’s welcome, Time hailed him as “Horowitz, Liberace and Presley all rolled into one.” Two days after his triumphant homecoming, he recorded the Rachmaninoff Third and 11 days later the Tchaikovsky First, the concertos with which he had won the final round of the Competition, both in Carnegie Hall with Kirill Kondrashin, the conductor who had accompanied him. Released to huge acclaim, the Tchaikovsky became the first million-selling classical LP. But that was in 1958. What of the music? In liner notes to the Rachmaninoff LP, David Sarnoff wrote: “If one seeks an explanation for Van Cliburn’s magnetism, I would simply say that it is musical control coupled with spontaneous beauty.” In the New Yorker, Winthrop Sargeant called Cliburn the “living representative of the great 19th and early 20th century school of virtuosity” with tasteful rubato, a sure sense of phrasing, feeling for restraint and an overall musical sensitivity. That about sums it up – despite potent technique, Cliburn eschews thundering keyboard power for masterful, solid warmth. Such a style seems authentic. The best comparison for the Tchaikovsky is the magnificent 1926 recording by Vassily Sapellnikoff, whom the composer considered his foremost exponent; while it’s generally faster (perhaps to fit onto eight 12-inch sides) and begins with impetuous phrasing and huge dynamic accents, it soon settles into lyric elegance. Rachmaninoff’s own 1939 recording of his Third with Ormandy and the Philadelphia Orchestra reflects similar moderation and refinement. The rest of this collection presents a deeply-felt live 1960 Moscow taping of the Rachmaninoff Sonata # 2, and a 1970s collection of short pieces. Among these, perhaps the most surprising is the Etude-Tableau in e-flat minor which avoids a temptation to storm the heavens for equally effective heart-melting pleading. While much of his other work tended to be overlooked, within the limits of his narrow repertoire Cliburn still comes across as a musical champion. the lanky young Texan ventured to Moscow where he won the first Tchaikovsky Competition and wowed Russian audiences with his open attitude and magnificent playing of “their” music. When he returned home to a ticker-tape parade and a hero’s welcome, Time hailed him as “Horowitz, Liberace and Presley all rolled into one.” Two days after his triumphant homecoming, he recorded the Rachmaninoff Third and 11 days later the Tchaikovsky First, the concertos with which he had won the final round of the Competition, both in Carnegie Hall with Kirill Kondrashin, the conductor who had accompanied him. Released to huge acclaim, the Tchaikovsky became the first million-selling classical LP. But that was in 1958. What of the music? In liner notes to the Rachmaninoff LP, David Sarnoff wrote: “If one seeks an explanation for Van Cliburn’s magnetism, I would simply say that it is musical control coupled with spontaneous beauty.” In the New Yorker, Winthrop Sargeant called Cliburn the “living representative of the great 19th and early 20th century school of virtuosity” with tasteful rubato, a sure sense of phrasing, feeling for restraint and an overall musical sensitivity. That about sums it up – despite potent technique, Cliburn eschews thundering keyboard power for masterful, solid warmth. Such a style seems authentic. The best comparison for the Tchaikovsky is the magnificent 1926 recording by Vassily Sapellnikoff, whom the composer considered his foremost exponent; while it’s generally faster (perhaps to fit onto eight 12-inch sides) and begins with impetuous phrasing and huge dynamic accents, it soon settles into lyric elegance. Rachmaninoff’s own 1939 recording of his Third with Ormandy and the Philadelphia Orchestra reflects similar moderation and refinement. The rest of this collection presents a deeply-felt live 1960 Moscow taping of the Rachmaninoff Sonata # 2, and a 1970s collection of short pieces. Among these, perhaps the most surprising is the Etude-Tableau in e-flat minor which avoids a temptation to storm the heavens for equally effective heart-melting pleading. While much of his other work tended to be overlooked, within the limits of his narrow repertoire Cliburn still comes across as a musical champion.

- Alfred Cortot (1877 - 1962) - Cortot most often is mentioned nowadays for two traits. This first is a quality of free expression that permeates his performances.

Alfred Brendel called it control in the guise of improvisation and characterized Cortot’s playing as three-dimensional, “equally satisfying my mind, my senses and my emotions.” Indeed, his spontaneous approach, while occasionally seeming a random affectation (as in his volatile 1926 Liszt Hungarian Rhapsody # 2 heard here), constantly impresses as an effort to elucidate the structure and distinctive essence of a piece. Such a method seems essential in the rambling expanses of Franck (here, the Prelude, choral et fugue, the Prelude, aria et final and the Variations symphoniques), helpful to illuminate the tonal meandering of Debussy (here, the Preludes, Book I), and especially fascinating in the well-worn Preludes and Études of Chopin, where fresh direction is welcome and where Cortot constantly probes to challenge our assumptions. The other quality, alas, is technical imprecision. As Harold Schonberg notes, Cortot was not only a preeminent soloist, but a famed conductor, chamber musician, teacher, educator, editor and author. With such multi-faceted demanding careers, “How could he possibly find time to keep his fingers in shape? The answer is simple: he didn’t.” Indeed, his recordings show a precipitous decline in technique, beginning with his near-perfect Victor acousticals (represented here by a 1923 Ravel Jeux d’eau) and superb trios with Casals and Thibaud (readily available on Naxos and elsewhere), slipping somewhat in his early electrical solos, and sadly diminished in his LP remakes. The unfortunate culmination is on clear display in his Schumann here. Although the album credits mislabel his Études symphoniques and Carnaval as his acclaimed 1928-9 versions, they in fact are his 1953 remakes, of perverse interest to collectors but otherwise crude and graceless compared to the versions they purport to be. (The 1935 Kreisleriana was his only recording, according to the discography compiled by Farhan Malik, but it's far from flawless.) Yet, even those impress in a way – the sheer feeling behind the playing combines with the flaws to produce a pervasive quality of humanity that enhances Cortot’s achievement and seems a small price to pay to relive his inspired and impulsive poetry. Alfred Brendel called it control in the guise of improvisation and characterized Cortot’s playing as three-dimensional, “equally satisfying my mind, my senses and my emotions.” Indeed, his spontaneous approach, while occasionally seeming a random affectation (as in his volatile 1926 Liszt Hungarian Rhapsody # 2 heard here), constantly impresses as an effort to elucidate the structure and distinctive essence of a piece. Such a method seems essential in the rambling expanses of Franck (here, the Prelude, choral et fugue, the Prelude, aria et final and the Variations symphoniques), helpful to illuminate the tonal meandering of Debussy (here, the Preludes, Book I), and especially fascinating in the well-worn Preludes and Études of Chopin, where fresh direction is welcome and where Cortot constantly probes to challenge our assumptions. The other quality, alas, is technical imprecision. As Harold Schonberg notes, Cortot was not only a preeminent soloist, but a famed conductor, chamber musician, teacher, educator, editor and author. With such multi-faceted demanding careers, “How could he possibly find time to keep his fingers in shape? The answer is simple: he didn’t.” Indeed, his recordings show a precipitous decline in technique, beginning with his near-perfect Victor acousticals (represented here by a 1923 Ravel Jeux d’eau) and superb trios with Casals and Thibaud (readily available on Naxos and elsewhere), slipping somewhat in his early electrical solos, and sadly diminished in his LP remakes. The unfortunate culmination is on clear display in his Schumann here. Although the album credits mislabel his Études symphoniques and Carnaval as his acclaimed 1928-9 versions, they in fact are his 1953 remakes, of perverse interest to collectors but otherwise crude and graceless compared to the versions they purport to be. (The 1935 Kreisleriana was his only recording, according to the discography compiled by Farhan Malik, but it's far from flawless.) Yet, even those impress in a way – the sheer feeling behind the playing combines with the flaws to produce a pervasive quality of humanity that enhances Cortot’s achievement and seems a small price to pay to relive his inspired and impulsive poetry.

- Gyorgy Cziffra (1921 - 1994) - While the temptation to match artistic temperament with biographical background often fails, it’s hard to dismiss the impact Cziffra’s gypsy parentage,

time as a POW, three years of hard labor and ultimate escape to Vienna must have had in shaping his outlook. Cziffra’s complete 1962 set of the Chopin Études is frighteningly intense, as he constantly upends expectations and peers deeply into the darkest regions of the composer’s soul. Thus, the very first étude is deliberately lumpy, the second mechanically joyless, the “Black Key” brittle and drained of all its accustomed grace, the C# minor thrashingly violent and full of rhythmic and dynamic distension, the “Revolutionary” suffused with anguish, and Op. 25, # 7 so tortured with impatience that it’s simply impossible to beat its time. This is a deeply challenging, exhausting encounter, utterly unique among all the fine, idiomatic renditions on record. (The CD closes, though, with a “Heroic” Polonaise that’s equally puzzling – restrained, gentle and barely inflected.) The other CD will be far less controversial – a collection of Liszt powerhouse pieces that unquestionably fit Cziffra’s volatile and edgy temperament, ranging from the pristine beauty of the Sonetto 123 del Petrarca and the profound peace of “Un sospiro” to the severe formality of the Fantasy and Fugue on the Name B-A-C-H, the spiritual elevation of the Legende No. 2, the heroism of the Polonaise No. 2 and the dense volitility of the Mephisto Waltz No. 1 time as a POW, three years of hard labor and ultimate escape to Vienna must have had in shaping his outlook. Cziffra’s complete 1962 set of the Chopin Études is frighteningly intense, as he constantly upends expectations and peers deeply into the darkest regions of the composer’s soul. Thus, the very first étude is deliberately lumpy, the second mechanically joyless, the “Black Key” brittle and drained of all its accustomed grace, the C# minor thrashingly violent and full of rhythmic and dynamic distension, the “Revolutionary” suffused with anguish, and Op. 25, # 7 so tortured with impatience that it’s simply impossible to beat its time. This is a deeply challenging, exhausting encounter, utterly unique among all the fine, idiomatic renditions on record. (The CD closes, though, with a “Heroic” Polonaise that’s equally puzzling – restrained, gentle and barely inflected.) The other CD will be far less controversial – a collection of Liszt powerhouse pieces that unquestionably fit Cziffra’s volatile and edgy temperament, ranging from the pristine beauty of the Sonetto 123 del Petrarca and the profound peace of “Un sospiro” to the severe formality of the Fantasy and Fugue on the Name B-A-C-H, the spiritual elevation of the Legende No. 2, the heroism of the Polonaise No. 2 and the dense volitility of the Mephisto Waltz No. 1

- Christoph Eschenbach (b. 1940) - Here is another bold, exciting performer who transforms everything he encounters with sensationally clean articulation into a vibrant,

living experience. But for every rule there's an exception, and here it's a more earth-bound Beethoven First Concerto with von Karajan, to whose literalism Eschenbach bends his own inspiration to produce a strong if characterless reading in which the extended four-minute cadenza and an exquisite adagio speak more eloquently than the rest. The rest of his program is both generous (both discs run over 80 minutes) and striking - breathtakingly swift Haydn sonatas, precise and eloquent Mozart (the "Ah, vous dirai-je, Maman" Variations and the Sonata in F, K. 332), sparkling early Schumann (the "Abegg" Variations and Op. 4 Intermezzi) and a sharply-etched Schubert Sonata in A, D. 959. living experience. But for every rule there's an exception, and here it's a more earth-bound Beethoven First Concerto with von Karajan, to whose literalism Eschenbach bends his own inspiration to produce a strong if characterless reading in which the extended four-minute cadenza and an exquisite adagio speak more eloquently than the rest. The rest of his program is both generous (both discs run over 80 minutes) and striking - breathtakingly swift Haydn sonatas, precise and eloquent Mozart (the "Ah, vous dirai-je, Maman" Variations and the Sonata in F, K. 332), sparkling early Schumann (the "Abegg" Variations and Op. 4 Intermezzi) and a sharply-etched Schubert Sonata in A, D. 959.

- Edwin Fischer (1886 - 1960), volume 1 - Nowadays we are so used to "authentic" period renditions of Bach played with phenomenal precision on original instruments

that we tend to forget that there is another way to approach this most universal of all composers. Fischer is a glorious throwback who plays his Bach on the concert grand with an exquisite velvet touch and boatloads of personal inflection. While his renditions of three piano concertos and excerpts from "The 48" are revelatory, especially startling are three fantasy pieces, in which his free-wheeling departures from modern interpretive expectations are especially strong and uniquely compelling. Which style is truly the more authentic? From a purely emotional point of view, they're equally valid and only serve to prove the futility of aesthetic arguments in face of the transcendent universality of Bach's timeless art. that we tend to forget that there is another way to approach this most universal of all composers. Fischer is a glorious throwback who plays his Bach on the concert grand with an exquisite velvet touch and boatloads of personal inflection. While his renditions of three piano concertos and excerpts from "The 48" are revelatory, especially startling are three fantasy pieces, in which his free-wheeling departures from modern interpretive expectations are especially strong and uniquely compelling. Which style is truly the more authentic? From a purely emotional point of view, they're equally valid and only serve to prove the futility of aesthetic arguments in face of the transcendent universality of Bach's timeless art.

- Edwin Fischer, volume 2 - Fischer's first volume is devoted to his lovely, rich, old-fashioned Bach. The second, exploring the rest of the core German

repertoire in which he specialized, is fueled by two marvelous concerto recordings. His 1933 account of the Mozart Concerto # 20 is lean, pointed, vital and heartfelt without sentimentality. His 1951 reading of the Beethoven Emperor with Furtwangler and the Philharmonia generates a far different excitement, charged with spiritual drama from the closely-attuned philosophical interplay of soloist and conductor deeply immersed in German tradition. The second disc presents the Mozart Fantasia in c minor, K. 475, the Schubert Impromptus, D. 899 and the Beethoven Appassionata and Op. 110 Sonatas, all played with a direct, natural, self-effacing and utterly convincing manner that sounds ineffably right. Fischer's art is not colorful, but it has infinite degrees of careful shading. repertoire in which he specialized, is fueled by two marvelous concerto recordings. His 1933 account of the Mozart Concerto # 20 is lean, pointed, vital and heartfelt without sentimentality. His 1951 reading of the Beethoven Emperor with Furtwangler and the Philharmonia generates a far different excitement, charged with spiritual drama from the closely-attuned philosophical interplay of soloist and conductor deeply immersed in German tradition. The second disc presents the Mozart Fantasia in c minor, K. 475, the Schubert Impromptus, D. 899 and the Beethoven Appassionata and Op. 110 Sonatas, all played with a direct, natural, self-effacing and utterly convincing manner that sounds ineffably right. Fischer's art is not colorful, but it has infinite degrees of careful shading.

- Leon Fleisher (b. 1928) - This set, to me, is a sadly missed opportunity. Although not by choice, Fleisher has established a unique reputation as a champion and superb

interpreter of the literature for the left hand alone. All we get here of it, though, is the Ravel Concerto for the Left Hand. Fleisher's performance is superb, but it's hardly unique; indeed, those of Katchen and Casadesus are included in their volumes of this same Edition. The rest of the Fleisher set consists of his youthful records of Liszt, Copland, Mozart and Weber sonatas, recorded prior to the mid-sixties when he lost the use of his right hand to a nervous affliction. (Most recently, has recovered its use and issued an album of two-hand music to great acclaim.) Fine as these are, the producers missed a great opportunity to present Fleisher in a realm in which he alone reigns supreme. The left-handed literature may not overflow with great masterpieces, but it provides a fascinating demonstration of using musical resources to overcome fearsome limitations. And perhaps that is the ultimate value of such pieces -- they epitomize the wonder of art, which uses everyday materials within structural confines to lift us above the physical world into a far more extraordinary and limitless one. The portrait of Fleisher presented here is one of sad regret, of a brilliant standard career cruelly cut short by tragedy. More valuable would have been the musical proof of an intensely uplifting human drama of triumphing over crushing odds. We can hear lots of great Liszt and Mozart (even in this very Edition), but to whom else can we turn for a Toccata by Takacs? interpreter of the literature for the left hand alone. All we get here of it, though, is the Ravel Concerto for the Left Hand. Fleisher's performance is superb, but it's hardly unique; indeed, those of Katchen and Casadesus are included in their volumes of this same Edition. The rest of the Fleisher set consists of his youthful records of Liszt, Copland, Mozart and Weber sonatas, recorded prior to the mid-sixties when he lost the use of his right hand to a nervous affliction. (Most recently, has recovered its use and issued an album of two-hand music to great acclaim.) Fine as these are, the producers missed a great opportunity to present Fleisher in a realm in which he alone reigns supreme. The left-handed literature may not overflow with great masterpieces, but it provides a fascinating demonstration of using musical resources to overcome fearsome limitations. And perhaps that is the ultimate value of such pieces -- they epitomize the wonder of art, which uses everyday materials within structural confines to lift us above the physical world into a far more extraordinary and limitless one. The portrait of Fleisher presented here is one of sad regret, of a brilliant standard career cruelly cut short by tragedy. More valuable would have been the musical proof of an intensely uplifting human drama of triumphing over crushing odds. We can hear lots of great Liszt and Mozart (even in this very Edition), but to whom else can we turn for a Toccata by Takacs?

- Samson François (1924 - 1970) – One of the least known pianists in this edition, François is barely mentioned in most references, but surely deserves inclusion.

As a student of Cortot, Long and Lefebure, he was solidly trained in the French tradition, but his interest in jazz and movies stimulated a remarkable sense of freedom and improvisation in his playing, which declined well before his life ended (at age 46) due to a reckless spendthrift lifestyle and a surfeit of alcohol, tobacco and drugs. The first disc applies his fascinating artistry to Chopin – Impromptus suffused with diffidence, a Sonata # 2 that begins with thorny brittle anger and subsides into mechanics drained of feeling, heavily inflected Waltzes with bumpy rhythms that defy dancing, and, most startling of all, the four Ballades – the first rollicking and vibrant, the second fitfully stormy and brooding, the third suitably becalmed and a restless fourth that teases with initial placidity. After squandering much of the second disc on lesser stuff comes excerpts from his startlingly unfettered 1961 survey of Debussy. A Clair de lune is no pale reverie, but a vibrant, shining beacon of complex reflections; rather, it is with L’isle joyeuse that François crafts a dense dream with rapidly-shifting moods, while Pour le Piano is earnest, fully-realized and multi-leveled. The collection ends with François’ first record, a stunning 1948 78 of his signature piece – "Scarbo" from Ravel’s Gaspard de la Nuit, thrashing with nervous outbursts from a raw, hallucinatory texture. Despite his obscurity, François is utterly unique, his deeply personal, free-wheeling style compelling a rethinking of familiar materials. As a student of Cortot, Long and Lefebure, he was solidly trained in the French tradition, but his interest in jazz and movies stimulated a remarkable sense of freedom and improvisation in his playing, which declined well before his life ended (at age 46) due to a reckless spendthrift lifestyle and a surfeit of alcohol, tobacco and drugs. The first disc applies his fascinating artistry to Chopin – Impromptus suffused with diffidence, a Sonata # 2 that begins with thorny brittle anger and subsides into mechanics drained of feeling, heavily inflected Waltzes with bumpy rhythms that defy dancing, and, most startling of all, the four Ballades – the first rollicking and vibrant, the second fitfully stormy and brooding, the third suitably becalmed and a restless fourth that teases with initial placidity. After squandering much of the second disc on lesser stuff comes excerpts from his startlingly unfettered 1961 survey of Debussy. A Clair de lune is no pale reverie, but a vibrant, shining beacon of complex reflections; rather, it is with L’isle joyeuse that François crafts a dense dream with rapidly-shifting moods, while Pour le Piano is earnest, fully-realized and multi-leveled. The collection ends with François’ first record, a stunning 1948 78 of his signature piece – "Scarbo" from Ravel’s Gaspard de la Nuit, thrashing with nervous outbursts from a raw, hallucinatory texture. Despite his obscurity, François is utterly unique, his deeply personal, free-wheeling style compelling a rethinking of familiar materials.

- Ignaz Friedman (1882 - 1848) - Best known for his bold, deeply individual style, Friedman's recordings often thwart our conventional expectations. This edition presents most of them,

omitting retakes and salon fluff (including his own compositions) that are collected complete on Pearl IF 2000. His Chopin, while often seeming to reflect his own idiosyncratic personality, does have a claim to authenticity, as he was trained in Chopin's culture and researched the approaches of Chopin's own students when compiling his edition of the complete Chopin works. Thus, as his biographer Allan Evans points out, while Friedman's set of 12 mazurkas seems quirky, with bizarre rhythmic lapses, they deliberately synthesize classical regularity with genuine folk elements of stretched beats and agogic accents, similar to the dances with which Friedman was familiar as a rural Polish child. He also departs from the Chopin norm with a consistently sunny "Raindrop" Prelude, an Etude in C (Op. 10, #7) with an exciting snarl, a "Minute" Waltz that's supernaturally swift, and a "Heroic" Polonaise propelled by dramatic lurches and pauses, as if to be sure we know just who dominates this partnership between composer and performer. Aside from an assertive Beethoven "Kreutzer" Sonata with Huberman (not included here, but on Naxos), full of daring tension, the only complete major work Friedman recorded was the Beethoven "Moonlight" Sonata in which he logically extends the gentle opening through the often brusque finale. Other highlights include a rip-roaring Liszt Hungarian Rhapsody # 12, a Weber Invitation to the Dance that's deeply intimate not only in the introduction but throughout, a Rubinstein Valse caprice that's shaped with dramatic thrust, and a set of Mendelssohn Songs Without Words that seem elevated above the mundane by treating each piece with the respect merited by more substantial music. omitting retakes and salon fluff (including his own compositions) that are collected complete on Pearl IF 2000. His Chopin, while often seeming to reflect his own idiosyncratic personality, does have a claim to authenticity, as he was trained in Chopin's culture and researched the approaches of Chopin's own students when compiling his edition of the complete Chopin works. Thus, as his biographer Allan Evans points out, while Friedman's set of 12 mazurkas seems quirky, with bizarre rhythmic lapses, they deliberately synthesize classical regularity with genuine folk elements of stretched beats and agogic accents, similar to the dances with which Friedman was familiar as a rural Polish child. He also departs from the Chopin norm with a consistently sunny "Raindrop" Prelude, an Etude in C (Op. 10, #7) with an exciting snarl, a "Minute" Waltz that's supernaturally swift, and a "Heroic" Polonaise propelled by dramatic lurches and pauses, as if to be sure we know just who dominates this partnership between composer and performer. Aside from an assertive Beethoven "Kreutzer" Sonata with Huberman (not included here, but on Naxos), full of daring tension, the only complete major work Friedman recorded was the Beethoven "Moonlight" Sonata in which he logically extends the gentle opening through the often brusque finale. Other highlights include a rip-roaring Liszt Hungarian Rhapsody # 12, a Weber Invitation to the Dance that's deeply intimate not only in the introduction but throughout, a Rubinstein Valse caprice that's shaped with dramatic thrust, and a set of Mendelssohn Songs Without Words that seem elevated above the mundane by treating each piece with the respect merited by more substantial music.

- Andrei Gavrilov (b. 1955) - The notes attempt to neatly divide Gavrilov's career (so far) into two phases - that of a youthful firebrand in Russia, and then a mature international outlook after his emigration in 1984.

But this simplistic chronology is belied by his passionate 1993 Bach French Suite # 6 and a wistful 1973 Handel Suite in d minor. Rather, this program boasts brilliant virtuosity, constantly evolving and consistently serving the cause of a wide variety of music - a strongly characterized Chopin Ballade # 2, exciting Tchaikovsky Theme and Variations, a probing Mozart Fantasia in d minor, a potent Prokofiev Concerto # 1, rich Rachmaninov Moments Musicaux, a fiery Scriabin Sonata # 4 and wondrous excerpts from Prokofiev's Romeo and Juliet ballet, all capped by a stunning account of Balakirev's Islamey. The only curiosity is a weighty Schumann Papillons that emerges more as an iron butterfly than a dappled flight of imagination. Both in variety and execution, this is a breathtaking volume. But this simplistic chronology is belied by his passionate 1993 Bach French Suite # 6 and a wistful 1973 Handel Suite in d minor. Rather, this program boasts brilliant virtuosity, constantly evolving and consistently serving the cause of a wide variety of music - a strongly characterized Chopin Ballade # 2, exciting Tchaikovsky Theme and Variations, a probing Mozart Fantasia in d minor, a potent Prokofiev Concerto # 1, rich Rachmaninov Moments Musicaux, a fiery Scriabin Sonata # 4 and wondrous excerpts from Prokofiev's Romeo and Juliet ballet, all capped by a stunning account of Balakirev's Islamey. The only curiosity is a weighty Schumann Papillons that emerges more as an iron butterfly than a dappled flight of imagination. Both in variety and execution, this is a breathtaking volume.

- Walter Gieseking (1895-1956), Volume 1 - Although best remembered for his superlative Debussy and Ravel recordings (included in his volume 2, discussed below),

in his time Geiseking played an even more important role. Nowadays, Mozart has taken his rightful place alongside Bach and Beethoven as a supreme master, but barely a century ago nearly all his output beyond the late symphonies and operas were dismissed as rococo trivia. Gieseking’s pioneering LP traversal of Mozart’s complete solo piano music awakened much of the world to its splendor. While Gieseking’s mild interpretive approach seems somewhat attenuated in light of our modern view, in which we tend to attribute to Mozart a more expansive realm of human emotion, Gieseking presented Mozart with a simple sincerity that accorded him a respect that compelled reevaluation and led, in part, to his current esteem. The full cycle is readily available on EMI; instead, here we have his recordings with Karajan and the Philharmonia of the Piano Concertos 23 and 24, which (despite blurred, overloaded recordings) fully convey his clean classicism, treating Mozart neither as a budding romantic nor a precious miniaturist. Also here are the 1951 Karajan/Philharmonia Beethoven Concertos 4 and 5. The latter, in particular, serves as an ideal vehicle for Gieseking’s style, its exquisite adagio framed by the outer movements in which Beethoven lets his orchestra do the heavy lifting, leaving the soloist to revel in delicate adornment. Karajan provides an objective, emotionally-neutral backdrop in which Gieseking’s subtly expressive playing is effectively nestled. The same forces join in a dry and reticent Franck Symphonic Variations which seems bland compared to a number of more spirited accounts. in his time Geiseking played an even more important role. Nowadays, Mozart has taken his rightful place alongside Bach and Beethoven as a supreme master, but barely a century ago nearly all his output beyond the late symphonies and operas were dismissed as rococo trivia. Gieseking’s pioneering LP traversal of Mozart’s complete solo piano music awakened much of the world to its splendor. While Gieseking’s mild interpretive approach seems somewhat attenuated in light of our modern view, in which we tend to attribute to Mozart a more expansive realm of human emotion, Gieseking presented Mozart with a simple sincerity that accorded him a respect that compelled reevaluation and led, in part, to his current esteem. The full cycle is readily available on EMI; instead, here we have his recordings with Karajan and the Philharmonia of the Piano Concertos 23 and 24, which (despite blurred, overloaded recordings) fully convey his clean classicism, treating Mozart neither as a budding romantic nor a precious miniaturist. Also here are the 1951 Karajan/Philharmonia Beethoven Concertos 4 and 5. The latter, in particular, serves as an ideal vehicle for Gieseking’s style, its exquisite adagio framed by the outer movements in which Beethoven lets his orchestra do the heavy lifting, leaving the soloist to revel in delicate adornment. Karajan provides an objective, emotionally-neutral backdrop in which Gieseking’s subtly expressive playing is effectively nestled. The same forces join in a dry and reticent Franck Symphonic Variations which seems bland compared to a number of more spirited accounts.

- Walter Gieseking, Volume 2 - I'm deeply torn over this set. Artistically, it's consistently sensational and it ends with one of the greatest piano recordings

ever made - Gieseking's 1937/8 Ravel Gaspard de la Nuit. The exquisite subtlety of Gieseking's touch, the astounding color he conjures, and the sheer flow of his notes are absolutely breathtaking. And yet, much of the wonder is ruined by miserable transfers. In a sadly misguided (and largely unsuccessful) attempt to reduce the surface noise (of which plenty remains), the music is stripped of both bass and treble, leaving a boxy, synthetic sound that barely resembles a piano. Both the original LP transfer on Columbia ML 4773 and a prior CD on Pearl 9449 preserve the tonal richness and convey the depth of Gieseking's extraordinary sound. Such a shame! Equally lousy transfers diminish the marvels of Debussy's first book of Preludes and his Estampes. Swift and precise readings of the same vintage of Beethoven's Waldstein and Appassionata Sonatas come across somewhat better. If you can stand some increased "sizzle,"get the Pearl CD of the wondrous Debussy and Ravel. ever made - Gieseking's 1937/8 Ravel Gaspard de la Nuit. The exquisite subtlety of Gieseking's touch, the astounding color he conjures, and the sheer flow of his notes are absolutely breathtaking. And yet, much of the wonder is ruined by miserable transfers. In a sadly misguided (and largely unsuccessful) attempt to reduce the surface noise (of which plenty remains), the music is stripped of both bass and treble, leaving a boxy, synthetic sound that barely resembles a piano. Both the original LP transfer on Columbia ML 4773 and a prior CD on Pearl 9449 preserve the tonal richness and convey the depth of Gieseking's extraordinary sound. Such a shame! Equally lousy transfers diminish the marvels of Debussy's first book of Preludes and his Estampes. Swift and precise readings of the same vintage of Beethoven's Waldstein and Appassionata Sonatas come across somewhat better. If you can stand some increased "sizzle,"get the Pearl CD of the wondrous Debussy and Ravel.

- Emil Gilels (1916 - 1985), Volume 3 - The final volume devoted to the great Russian colossus emphasizes his lyric side. It begins with a 1972 account of the Brahms

Second with Eugen Jochum and the Berlin Philharmonic that deliberately eschews the dramatic challenges of the work but reaches extraordinary expressive heights, especially in the ravishing andante (ironically the movement in which the piano plays the least role). There's also a rarely-heard Clementi Sonata and an intense and powerful account of the duo-piano Schubert Fantasy, D. 940 in which Gilels is partnered by his daughter Elena, who reinforces his full-blooded yet searching approach. Perhaps most fascinating, though, are the two Chopin Sonatas. Op. 35, from a 1961 concert, bristles with elemental energy and nervous tension, especially in Gilels' jagged shaping of the propulsive phrases of the first movement. Op. 58 (from 1978) begins with a burst of quirky passion but then subsides into a beautifully flowing, leisurely (30 minutes, rather than the usual 24 or so), autumnal discourse. Four gorgeous Grieg Lyric Pieces top off a wonderful tribute to a well-rounded and deeply sensitive artist. Second with Eugen Jochum and the Berlin Philharmonic that deliberately eschews the dramatic challenges of the work but reaches extraordinary expressive heights, especially in the ravishing andante (ironically the movement in which the piano plays the least role). There's also a rarely-heard Clementi Sonata and an intense and powerful account of the duo-piano Schubert Fantasy, D. 940 in which Gilels is partnered by his daughter Elena, who reinforces his full-blooded yet searching approach. Perhaps most fascinating, though, are the two Chopin Sonatas. Op. 35, from a 1961 concert, bristles with elemental energy and nervous tension, especially in Gilels' jagged shaping of the propulsive phrases of the first movement. Op. 58 (from 1978) begins with a burst of quirky passion but then subsides into a beautifully flowing, leisurely (30 minutes, rather than the usual 24 or so), autumnal discourse. Four gorgeous Grieg Lyric Pieces top off a wonderful tribute to a well-rounded and deeply sensitive artist.

- Grigory Ginsburg (1904 - 1961) - Heard after the brilliance of Gavrilov, this volume serves as a reminder that traditional Russian piano playing is not the blinding virtuosity

and thundering energy of Gilels, Richter or Horowitz, but a far more refined and contemplative style - a reflection of conservative Russian society before the Revolution, when ideals were far closer to European nobility than unleashed Slavic passion. Thus, in Ginsburg's hands Beethoven's explosive Rondo a capriccio in G, Op. 129, aptly titled the "Rage Over the Lost Penny," sounds more like Mozart annoyed than Beethoven in a fury. Ginsburg's grand style brings a fine sense of structural unfolding to six Liszt Hungarian Rhapsodies, Tchaikovsky's Grande Sonate in G, two transcriptions of Eugene Onegin and obscurities from Medtner and Miaskovsky. But don't mistake Ginsburg's approach for a masking of uncertain technique; the glissandi in his Hungarian Rhapsody # 10 are stunning and the Prokofiev Sonata # 3 is suitably brilliant. It just goes to show that sometimes smoldering embers can provide as much heat as a roaring blaze. and thundering energy of Gilels, Richter or Horowitz, but a far more refined and contemplative style - a reflection of conservative Russian society before the Revolution, when ideals were far closer to European nobility than unleashed Slavic passion. Thus, in Ginsburg's hands Beethoven's explosive Rondo a capriccio in G, Op. 129, aptly titled the "Rage Over the Lost Penny," sounds more like Mozart annoyed than Beethoven in a fury. Ginsburg's grand style brings a fine sense of structural unfolding to six Liszt Hungarian Rhapsodies, Tchaikovsky's Grande Sonate in G, two transcriptions of Eugene Onegin and obscurities from Medtner and Miaskovsky. But don't mistake Ginsburg's approach for a masking of uncertain technique; the glissandi in his Hungarian Rhapsody # 10 are stunning and the Prokofiev Sonata # 3 is suitably brilliant. It just goes to show that sometimes smoldering embers can provide as much heat as a roaring blaze.

- Leopold Godowsky (1870 - 1938) - Those who heard him in private considered Godowsky the greatest pianist of his generation, but he reportedly was intimidated by public

performances and often sounds stiff on record. Indeed, the 12 Chopin Nocturnes heard here are charitably described in the liner notes as "earthbound," and that could be said as well of his Beethoven "Adieu" Sonata. The Schumann Carnival, Chopin Sonata # 2 and Grieg Ballade fare better, despite poor transfers; side 1 of the Grieg is badly damaged, unlike the transfer on Pearl 9133. Perhaps the finest piece is the Chopin Scherzo # 4, reconstituted from an acetate dub and a test pressing, in which, despite dreadful sound, Godowsky for once seems to catch fire and leave his inhibitions aside. But it's hard to separate one's reaction from the poignant circumstances of this recording - right after completing it, Godowsky suffered a stroke that ended his career; could he possibly have sensed that this might be his last performance? performances and often sounds stiff on record. Indeed, the 12 Chopin Nocturnes heard here are charitably described in the liner notes as "earthbound," and that could be said as well of his Beethoven "Adieu" Sonata. The Schumann Carnival, Chopin Sonata # 2 and Grieg Ballade fare better, despite poor transfers; side 1 of the Grieg is badly damaged, unlike the transfer on Pearl 9133. Perhaps the finest piece is the Chopin Scherzo # 4, reconstituted from an acetate dub and a test pressing, in which, despite dreadful sound, Godowsky for once seems to catch fire and leave his inhibitions aside. But it's hard to separate one's reaction from the poignant circumstances of this recording - right after completing it, Godowsky suffered a stroke that ended his career; could he possibly have sensed that this might be his last performance?

- Glenn Gould (1932 - 1982) - Here's a bizarre collection. Gould had a reputation as one of the most eccentric pianists, but somehow I don't think the producers programmed Gould's

volume with Byrd, Gibbons, Scarlatti, Bizet, Strauss and Berg as a salute to his artistic personality. Gould was arguably the most important Bach player of all time. His deeply personal ideas were both praised as brilliant and reviled as perverse but never ignored. Here, though, they are wholly ignored -- we get not a note of his Bach (or even his equally controversial Beethoven). Rather, his volume is filled with throwaway stuff peripheral to his artistry. The liner notes forthrightly acnowledge this gaping lapse and gallantly try to infer Gould's greatness from bare hints derived from the stuff that's included. But why? I can only assume that the licensing process here fell more than a bit short of the love-fest of cooperation suggested by the publicity surrounding the Edition. I suspect that Sony, for one, kept all the best Gould material for its own recently-completed Glenn Gould Edition (which, incidentally, is a huge ripoff, full-priced but with many of its discs barely half full). It's also worth noting that the only two artists absent from the sampler volume of this Edition are Gould and his Sony label-mate Rudolf Serkin, and that according to the intended release schedule printed in the sampler Gould was to have had two volumes, but one of his two numbers was later reassigned to Gieseking. volume with Byrd, Gibbons, Scarlatti, Bizet, Strauss and Berg as a salute to his artistic personality. Gould was arguably the most important Bach player of all time. His deeply personal ideas were both praised as brilliant and reviled as perverse but never ignored. Here, though, they are wholly ignored -- we get not a note of his Bach (or even his equally controversial Beethoven). Rather, his volume is filled with throwaway stuff peripheral to his artistry. The liner notes forthrightly acnowledge this gaping lapse and gallantly try to infer Gould's greatness from bare hints derived from the stuff that's included. But why? I can only assume that the licensing process here fell more than a bit short of the love-fest of cooperation suggested by the publicity surrounding the Edition. I suspect that Sony, for one, kept all the best Gould material for its own recently-completed Glenn Gould Edition (which, incidentally, is a huge ripoff, full-priced but with many of its discs barely half full). It's also worth noting that the only two artists absent from the sampler volume of this Edition are Gould and his Sony label-mate Rudolf Serkin, and that according to the intended release schedule printed in the sampler Gould was to have had two volumes, but one of his two numbers was later reassigned to Gieseking.

- Frederich Gulda (b. 1930), volume 2 - The turgid excerpt in the sampler scared me away from his first, all-Debussy and Ravel volume. Here, though, are extraordinary performances -

solidly classical but with brilliant touches of individuality. The Chopin Ballades are incredible, fast but not rushed and filled with invention and life. The Beethoven and Chopin Concertos # 1 boast chamber sonorities, decades ahead of modern, "authentic" versions. The liner notes, though, constantly tease with anticipation of the really great phase of Gulda's artistry that they claim would follow these ‘fifties records. Since Gulda isn't exactly a household name here in the Colonies, I'd like to have heard some of his real glories, but they're nowhere to be heard. The set concludes with a six-minute live jam with an unidentified jazz combo. Are the producers suggesting that jazz is a natural extension of traditional classical music (as indeed it is)? If so, then lots of other great pianists of the twentieth century beg to be included in future volumes - Jellyroll Morton, Fats Waller, Art Tatum, Erroll Garner, ... solidly classical but with brilliant touches of individuality. The Chopin Ballades are incredible, fast but not rushed and filled with invention and life. The Beethoven and Chopin Concertos # 1 boast chamber sonorities, decades ahead of modern, "authentic" versions. The liner notes, though, constantly tease with anticipation of the really great phase of Gulda's artistry that they claim would follow these ‘fifties records. Since Gulda isn't exactly a household name here in the Colonies, I'd like to have heard some of his real glories, but they're nowhere to be heard. The set concludes with a six-minute live jam with an unidentified jazz combo. Are the producers suggesting that jazz is a natural extension of traditional classical music (as indeed it is)? If so, then lots of other great pianists of the twentieth century beg to be included in future volumes - Jellyroll Morton, Fats Waller, Art Tatum, Erroll Garner, ...

- Clara Haskil (1895 - 1960) - It's hard to avoid the temptation to relate Clara Haskil's art to her difficult life. Yet, her tribulations (spine injuries, brain tumor, exile) led her playing along two diametrically opposed courses.