|

(... or how I had to stop listening in order to love the Bomb)

Early March 2003 — I always look forward to seeing my columns in print, but I truly had hoped that the editors would reject this one. I fantasized that tensions had eased and its relevance had passed. But, alas – my deadline arrived and we're still swamped by thoughts of war. Indeed, even aside from the daily banner headlines, constant news updates and security warnings, I sit in my downtown DC office in full Code Orange alert, a mere four blocks from the White House, amid all the heightened police patrols, helicopters, surveillance and sirens and it’s hard to think of much else. amid all the heightened police patrols, helicopters, surveillance and sirens and it’s hard to think of much else.

In such troubled times the rarified purity of fine art seems insignificant, a selfish and useless indulgence, an ineffective attempt to hide from terrible visions and debilitating fears. I’m powerless to evade the pervasive obsession that consumes us and I must leave to credentialed experts the weightier and far more relevant issues of the roots and solutions to our present crisis, of which my knowledge is strictly derivative and my opinions largely worthless. But I can offer a few regrettably timely thoughts on music and war.

Music has always played an integral role in war and its preparations and aftermath. From organizing formations to launching cavalry charges, the sounds of bugle calls, drumming and marching bands have marked routine, coordinated maneuvers, underlined ceremony, celebrated victory and mourned losses. But when it comes to war in music, the two rarely mix. In comparison to its prevalence in theatre, painting and movies, surprisingly little music actually depicts or refers to war itself. Even so, given their stock in trade, composers naturally have been attracted to the sheer sound of war. After all, the explosive power of munitions must have packed a huge visceral thrill in the prehistoric era before rock concerts, home theatres, mega-watt amps and subwoofers.

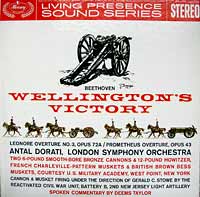

Curiously, while we revere him as one of the purest musical minds of all time, none other than Beethoven produced one of the few literal depictions of war in his 1813 Wellington’s Victory, or the Battle of Vittoria. Beethoven at first had so revered Napoleon as a populist liberator that he had offered the dedication of his remarkable Third Symphony, but inscribed it instead to “the memory of a great man” when Bonaparte proclaimed himself emperor. While Beethoven must have been genuinely thrilled at Napoleon’s defeat, his motivation was also mercenary. Wellington’s Victory was written for the Panharmonicon, a mechanical orchestra which covered its crudeness with a large battery of percussion. The contraption had been invented by his friend Johann Maelzel, who endeared himself to the increasingly deaf composer with another of his inventions, the ear-trumpet. Although barely more than an opportunistic and uninspired pastiche of national hymns and marching songs, the huge popularity of Wellington’s Victory boosted Beethoven’s fame and its sizable income bolstered his tenuous finances. none other than Beethoven produced one of the few literal depictions of war in his 1813 Wellington’s Victory, or the Battle of Vittoria. Beethoven at first had so revered Napoleon as a populist liberator that he had offered the dedication of his remarkable Third Symphony, but inscribed it instead to “the memory of a great man” when Bonaparte proclaimed himself emperor. While Beethoven must have been genuinely thrilled at Napoleon’s defeat, his motivation was also mercenary. Wellington’s Victory was written for the Panharmonicon, a mechanical orchestra which covered its crudeness with a large battery of percussion. The contraption had been invented by his friend Johann Maelzel, who endeared himself to the increasingly deaf composer with another of his inventions, the ear-trumpet. Although barely more than an opportunistic and uninspired pastiche of national hymns and marching songs, the huge popularity of Wellington’s Victory boosted Beethoven’s fame and its sizable income bolstered his tenuous finances.  When Beethoven toured the work in a version for live orchestra, his score specified the precise beats for each of 188 cannon shots and 25 volleys of musket fire, arrayed spatially to suggest the opposing armies. Its most famous recording, by Antal Dorati and the London Symphony for Mercury Living Presence, was a hi-fi spectacular, boasting authentic overdubbed ordnance from the West Point Museum, while a bonus cut on the LP presented audio tests and the actual field recordings of the shots and explosions. Wellington’s Victory clearly paved the way for Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture, another stylized clash of anthems in celebration of Napoleon’s defeat, whose slight musical merits are effectively eclipsed by the visual and sonic distraction of firework displays and batteries of cannon and artillery featured in nearly every modern performance and recording. When Beethoven toured the work in a version for live orchestra, his score specified the precise beats for each of 188 cannon shots and 25 volleys of musket fire, arrayed spatially to suggest the opposing armies. Its most famous recording, by Antal Dorati and the London Symphony for Mercury Living Presence, was a hi-fi spectacular, boasting authentic overdubbed ordnance from the West Point Museum, while a bonus cut on the LP presented audio tests and the actual field recordings of the shots and explosions. Wellington’s Victory clearly paved the way for Tchaikovsky’s 1812 Overture, another stylized clash of anthems in celebration of Napoleon’s defeat, whose slight musical merits are effectively eclipsed by the visual and sonic distraction of firework displays and batteries of cannon and artillery featured in nearly every modern performance and recording.

More common is the musical treatment of war on a symbolic level.  One of the earliest is found in Monteverdi’s 1638 Madrigali guerrieri ed amorosi (Madrigals of war and love). Yet, Monteverdi’s “war” pieces don’t depict or even refer to war itself, but rather function only as metaphor for the poet’s feelings of anguish and betrayal in love. In keeping with the unusual passion of the texts, the music introduced the then-innovative “agitated” style, which transcended the earlier pure contrapuntal method with dramatic devices of rapid scales, dotted rhythms, emphatic repetition and sudden shifting dynamics. Its contrast with the fluid, submissive tone of typical madrigals evokes the commotion of martial thoughts. One of the earliest is found in Monteverdi’s 1638 Madrigali guerrieri ed amorosi (Madrigals of war and love). Yet, Monteverdi’s “war” pieces don’t depict or even refer to war itself, but rather function only as metaphor for the poet’s feelings of anguish and betrayal in love. In keeping with the unusual passion of the texts, the music introduced the then-innovative “agitated” style, which transcended the earlier pure contrapuntal method with dramatic devices of rapid scales, dotted rhythms, emphatic repetition and sudden shifting dynamics. Its contrast with the fluid, submissive tone of typical madrigals evokes the commotion of martial thoughts.

More pointed in intent and effect was Haydn’s Missa in tempore belli (Mass in Time of War), written in 1796 as Napoleon was advancing on Vienna, where it was to be performed. Although in  the normally carefree key of C major and largely reflecting Haydn’s irrepressible buoyancy, the opening and closing sections are spiked with uncharacteristic (and, at the time, sacrilegious) militaristic trumpet fanfares and tympani rolls. (Haydn had added similar instrumentation to his earlier Symphony # 100 in G, but the effect was purely for decorative color.) While the Mass’s drums and brass accents are isolated, they inject a hint of anxiety and desperation into the final soothing prayer for peace. One of the hallmarks of great music is its ability to speak to future generations, and the Mass in Time of War did so with eloquence and cogency on January 19, 1973, when it highlighted a “Concert for Peace” led by Leonard Bernstein in Washington's National Cathedral as a protest to the Vietnam war and to the official Kennedy Center concert celebrating Nixon’s second inauguration that night. the normally carefree key of C major and largely reflecting Haydn’s irrepressible buoyancy, the opening and closing sections are spiked with uncharacteristic (and, at the time, sacrilegious) militaristic trumpet fanfares and tympani rolls. (Haydn had added similar instrumentation to his earlier Symphony # 100 in G, but the effect was purely for decorative color.) While the Mass’s drums and brass accents are isolated, they inject a hint of anxiety and desperation into the final soothing prayer for peace. One of the hallmarks of great music is its ability to speak to future generations, and the Mass in Time of War did so with eloquence and cogency on January 19, 1973, when it highlighted a “Concert for Peace” led by Leonard Bernstein in Washington's National Cathedral as a protest to the Vietnam war and to the official Kennedy Center concert celebrating Nixon’s second inauguration that night.

Nor was its point lost on Beethoven, who seized upon a similar device for the devastatingly effective conclusion of his 1822 Missa Solemnis.  Beethoven inscribed the final section of his score, “Prayer for inner and outer peace.” A gently rolling 6/8 melody points the way to a satisfying end to the vast spiritual journey of the preceding hour, but then drums pound and fanfares intrude, as soloists and then the full chorus, in clipped, terrified tones, turn their prayer for peace into a desperate plea. Just as their fears subside and the flowing music appears headed once more for the expected triumphant conclusion, the full orchestra interrupts with an angry fugue, capped by shrill blaring brass and thunderous percussive chords. Calm returns, only to fall utterly silent twice again to disclose the tympani still rumbling menacingly in the distance. At last the final cadence follows, but it’s brief and dutiful, a wholly unconvincing attempt to dispell the lingering qualms or to resolve such a massive and edgy structure. It’s at best an unsettled expression of faith, a troubling question rather than a rousing affirmation or a comforting spiritual meditation. Beethoven ends his most ambitious and arguably greatest work with a shrewd caution that a mind preoccupied with thoughts of war cannot be truly joyful or at ease. Beethoven inscribed the final section of his score, “Prayer for inner and outer peace.” A gently rolling 6/8 melody points the way to a satisfying end to the vast spiritual journey of the preceding hour, but then drums pound and fanfares intrude, as soloists and then the full chorus, in clipped, terrified tones, turn their prayer for peace into a desperate plea. Just as their fears subside and the flowing music appears headed once more for the expected triumphant conclusion, the full orchestra interrupts with an angry fugue, capped by shrill blaring brass and thunderous percussive chords. Calm returns, only to fall utterly silent twice again to disclose the tympani still rumbling menacingly in the distance. At last the final cadence follows, but it’s brief and dutiful, a wholly unconvincing attempt to dispell the lingering qualms or to resolve such a massive and edgy structure. It’s at best an unsettled expression of faith, a troubling question rather than a rousing affirmation or a comforting spiritual meditation. Beethoven ends his most ambitious and arguably greatest work with a shrewd caution that a mind preoccupied with thoughts of war cannot be truly joyful or at ease.

While Beethoven’s audiences may have had to infer his intention, Benjamin Britten left no room for doubt in his disquieting 1962 War Requiem.  In this first major work to seriously challenge sacred ritual, Britten intermingled the benign authority of the traditional liturgy of mourning with the poetry of Wilfred Owen, a British pacifist who was killed in battle at age 25, leaving a legacy of insightful poems. The sullen reality of Owen’s exquisitely sensitive but ineffably sad observations of disillusionment, pity and waste (sung at the premiere by English and German soloists) makes the rote liturgical platitudes of the chorus ring hollow. The sublime ending combines the customary prayer for everlasting peace and eternal rest with Owen’s prescient premonition of his own useless death, tinged with regret that the world’s vanity and arrogance would remain utterly unchanged. Britten prefaced his score with Owen’s fear that: “All a poet can do today is warn.” While Owens died shortly before the armistice ended World War I, his words seem chillingly apt in the diplomatic paralysis of our time. In this first major work to seriously challenge sacred ritual, Britten intermingled the benign authority of the traditional liturgy of mourning with the poetry of Wilfred Owen, a British pacifist who was killed in battle at age 25, leaving a legacy of insightful poems. The sullen reality of Owen’s exquisitely sensitive but ineffably sad observations of disillusionment, pity and waste (sung at the premiere by English and German soloists) makes the rote liturgical platitudes of the chorus ring hollow. The sublime ending combines the customary prayer for everlasting peace and eternal rest with Owen’s prescient premonition of his own useless death, tinged with regret that the world’s vanity and arrogance would remain utterly unchanged. Britten prefaced his score with Owen’s fear that: “All a poet can do today is warn.” While Owens died shortly before the armistice ended World War I, his words seem chillingly apt in the diplomatic paralysis of our time.

Beethoven and Britten imagined war powerfully but vicariously. Dmitri Shostakovich wrote most of his 1941 Symphony # 7 in Leningrad during the first two months of Nazi siege.  The composer would later claim that he really meant the work as an attack upon Stalin’s neglect of the city (“Stalin destroyed it and Hitler merely finished it off”), but throughout the war he proclaimed a more direct program. The first movement depicts an attack; in its infamous central episode a serene background is dispelled by a noisy and annoying march that incessantly worms its way through the entire orchestra with escalating intensity in a graceless and increasingly violent bolero. While often criticized as far too long for its thin materials (English critic Ernest Newman dubbed it as “so many degrees of longitude and platitude”), its vapid, shrill persistence aptly suggests war’s grueling oppression. After the march subsides into numb sorrow, the remaining movements conjure bittersweet dreams of better times, a wistful elegy for lost innocence and a powerful climax of eventual victory. Hailed as a timely symbol of the resistance, suffering and hopes of the Russian people, the “Leningrad” Symphony received hundreds of performances, both in Russia and abroad. In at least one sense, its portrayal of battle was taken literally, as Toscanini and Stokowski publicly fought for the US premiere after NBC imported the massive score on microfilm. Although the symphony’s esteem plummeted after the Allied victory, its harrowing portrait of a society stunned by war retains a relevant warning for our own time of anxiety. The composer would later claim that he really meant the work as an attack upon Stalin’s neglect of the city (“Stalin destroyed it and Hitler merely finished it off”), but throughout the war he proclaimed a more direct program. The first movement depicts an attack; in its infamous central episode a serene background is dispelled by a noisy and annoying march that incessantly worms its way through the entire orchestra with escalating intensity in a graceless and increasingly violent bolero. While often criticized as far too long for its thin materials (English critic Ernest Newman dubbed it as “so many degrees of longitude and platitude”), its vapid, shrill persistence aptly suggests war’s grueling oppression. After the march subsides into numb sorrow, the remaining movements conjure bittersweet dreams of better times, a wistful elegy for lost innocence and a powerful climax of eventual victory. Hailed as a timely symbol of the resistance, suffering and hopes of the Russian people, the “Leningrad” Symphony received hundreds of performances, both in Russia and abroad. In at least one sense, its portrayal of battle was taken literally, as Toscanini and Stokowski publicly fought for the US premiere after NBC imported the massive score on microfilm. Although the symphony’s esteem plummeted after the Allied victory, its harrowing portrait of a society stunned by war retains a relevant warning for our own time of anxiety.

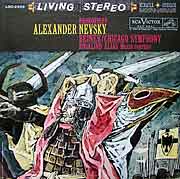

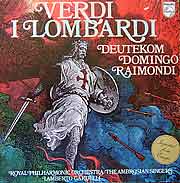

Whether subtly or directly, each of these works delivers a clear anti-war message, as do so many others. But our cherished tradition of democracy depends upon a variety of opinion and so, lest this survey seem unfair, I tried to achieve some balance with a few good pro-war pieces. I found period songs that served an immediate purpose to rally troops and civilians (the “Marine Corps Hymn,” Cohan’s “Over There”), works that properly honored the heroes who rose to their countries’ defense (Copland’s Lincoln Portrait, Prokofiev’s Alexander Nevsky), epic dramas and romances set in historical perspective (Berlioz's Les Troyens, Verdi’s I Lombardi alla Prima Crociata) and soundtracks to accompany TV and movie documentaries (Richard Rodger’s “Victory at Sea”). Searching deeper, there’s Chinese “Red Ballets,” Nazi oratorios and other forgettable junk ground out by faceless committees or written under coercion to glorify fascist regimes. But as for serious, enduring music with a pro-war perspective, I could find none at all.

And I think I know why.

Copyright 2003 by Peter Gutmann

|