|

For a version of this article without illustrations, please click here.

From the earliest

primal rite to the latest alternative rock, music has always served the same essential function: to forge promise from the routine of daily life, to expand our vision, to set us free. But all music opens vistas of broad future horizons. So if any one record can claim to be the most important of all, then it has to do even more: it must reveal some other path, one even more tightly shut than the gate to the future. It must unlock a door to the past, to something buried below the immediate roots of our modern music, to a level that lies deeper than even the oldest records that collectors love to cherish and explore. music has always served the same essential function: to forge promise from the routine of daily life, to expand our vision, to set us free. But all music opens vistas of broad future horizons. So if any one record can claim to be the most important of all, then it has to do even more: it must reveal some other path, one even more tightly shut than the gate to the future. It must unlock a door to the past, to something buried below the immediate roots of our modern music, to a level that lies deeper than even the oldest records that collectors love to cherish and explore.

Appreciation of any culture, including our own, begins in understanding its foundations. Ironically, while

musicologists have succeeded in reconstructing performance practices of the Baroque and

even the Renaissance, the far more recent romantic era (roughly coinciding with the nineteenth

century) continues to elude a consensus. And yet, it was that very epoch of unbounded

emotional freedom, exploration and discovery which, more than any other, paved the way

toward the liberated music of our own time. If we could only experience the romantic era

first-hand, even for a brief moment, it would vastly enrich our feelings for the present.

But just how did the music

of the years right before the phonograph actually sound? This remains a frustrating and

impenetrable mystery. Literary descriptions are imprecise, memories have faded and

scholars can only speculate. Perhaps the key to solving this puzzle lies in the groove of

an obscure early record.

The origin of the

phonograph held little promise of its ultimate value.  History tells us that the first

record was made in 1877 by Thomas Edison, who recited "Mary Had a Little Lamb"

onto a tinfoil cylinder and played it back to an astonished staff. Unfortunately for

posterity, Edison's choice of "Mary" was a woeful herald of the initial

development of his marvel. History tells us that the first

record was made in 1877 by Thomas Edison, who recited "Mary Had a Little Lamb"

onto a tinfoil cylinder and played it back to an astonished staff. Unfortunately for

posterity, Edison's choice of "Mary" was a woeful herald of the initial

development of his marvel.

Edison conceived and first

marketed his machine as a dictation device, and only grudgingly stooped to cheapen it to

such an impractical purpose as mere entertainment. Even then, catalogues of Edison records

through the late 1890s overflowed with mawkish recitations, maudlin songs and other

Victorian trivia. The closest these early efforts ever came to serious music were marches

and band arrangements of heavily cut light classical pieces. Edison may have been a genius

at invention, but his musical taste was appalling.

Edison's control over the

manufacture and marketing of records enabled him to dictate the content of commercial

recordings for the rest of the century. As an interesting aside, Edison exerted comparable

command over the other entertainment wonder of the age, motion pictures, effectively

limiting their first decade to vaudeville turns. In retrospect, it is amazing and sad how

one man's dreary and abysmal taste so thoroughly compromised both our aural and visual

records of the culture of the late nineteenth century.

It is safe to say that

until 1900 no artist of any stature made commercial records. The only seeming exception

was Ellen Beach Yaw, who cut several sides for Berliner's Gramophone in March 1899. But

hers is the exception that proves the rule. Promoted as "Lark Ellen," Miss Yaw

apparently was known more as a vocal gymnast than as a serious artist. Indeed, she is

believed to have sung only two opera performances in her life. Among her dubious talents

were an ability to sing an octave higher than normal soprano range and to perform a trill

in thirds rather than seconds. Collected on Pearl CD 9239, her records illustrate these

feats but little else. Surely, Lark Ellen was promoted not as a serious artist but as a

freak curiosity, comparable to the boxing dogs, butterfly dances and occasional trick

films that crowd early movie catalogues. The only seeming exception

was Ellen Beach Yaw, who cut several sides for Berliner's Gramophone in March 1899. But

hers is the exception that proves the rule. Promoted as "Lark Ellen," Miss Yaw

apparently was known more as a vocal gymnast than as a serious artist. Indeed, she is

believed to have sung only two opera performances in her life. Among her dubious talents

were an ability to sing an octave higher than normal soprano range and to perform a trill

in thirds rather than seconds. Collected on Pearl CD 9239, her records illustrate these

feats but little else. Surely, Lark Ellen was promoted not as a serious artist but as a

freak curiosity, comparable to the boxing dogs, butterfly dances and occasional trick

films that crowd early movie catalogues.

A fascinating recompense

lay in the activity of Gianni Bettini, an inventor who improved the diaphragm and stylus of the Edison apparatus to obtain more listenable results. Equally important, Bettini was a wealthy New York host who entertained the elite of the opera world in his home and took

the opportunity to record his guests throughout the 1890s. While copies of Bettini's

cylinders were very expensive (up to six dollars when the norm was fifty cents) and had

small distribution, his catalogue eventually ran to dozens of pages and read like a

"who's who" of opera. Yet, only a handful of Bettini's

intriguing but fragile cylinders have survived. an inventor who improved the diaphragm and stylus of the Edison apparatus to obtain more listenable results. Equally important, Bettini was a wealthy New York host who entertained the elite of the opera world in his home and took

the opportunity to record his guests throughout the 1890s. While copies of Bettini's

cylinders were very expensive (up to six dollars when the norm was fifty cents) and had

small distribution, his catalogue eventually ran to dozens of pages and read like a

"who's who" of opera. Yet, only a handful of Bettini's

intriguing but fragile cylinders have survived.

Another fascinating forebear of commercial recording arose in 1900, when Lionel Mapleson, the librarian of the Metropolitan Opera, began recording two-minute snippets during live performances with an Edison cylinder machine perched on the overhead flies – until 1903 when it crashed to the stage, barely missing a diva. Shortly before his death in 1937 he bequeathed his entire collection to the International Record Collectors’ Club, which reissued them on 78 and then LP. The noise level often is staggering, the balances skewed, the fidelity dreadful, and endings abrupt (some in mid-note) but they afford unique glimpses of artists who never recorded as well as vital souvenirs of others outside the constraints of the studio. the librarian of the Metropolitan Opera, began recording two-minute snippets during live performances with an Edison cylinder machine perched on the overhead flies – until 1903 when it crashed to the stage, barely missing a diva. Shortly before his death in 1937 he bequeathed his entire collection to the International Record Collectors’ Club, which reissued them on 78 and then LP. The noise level often is staggering, the balances skewed, the fidelity dreadful, and endings abrupt (some in mid-note) but they afford unique glimpses of artists who never recorded as well as vital souvenirs of others outside the constraints of the studio.

And then, suddenly, with

the turn of the century, the commercial floodgates opened.

The first to venture into

the void were singers, led by several celebrities of the Russian Imperial Opera who

recorded in 1901. There followed an extraordinary proliferation of fine vocal records by

the likes of Plançon, Scotti, Ruffo, Calvé, Tetrazzini, Schumann-Heink, Slezak, de

Lucia, Battistini and Caruso. Within a few short years, nearly every opera star succumbed

to recording. As a result, we have an embarrassment of riches – a nearly complete picture

of classical singing as it existed at the turn of the century. Instrumentalists soon would

follow. Irretrievably lost, though, was the cream of the previous generation, whose

artistry had soared while Edison immortalized whistlers and coon songs. led by several celebrities of the Russian Imperial Opera who

recorded in 1901. There followed an extraordinary proliferation of fine vocal records by

the likes of Plançon, Scotti, Ruffo, Calvé, Tetrazzini, Schumann-Heink, Slezak, de

Lucia, Battistini and Caruso. Within a few short years, nearly every opera star succumbed

to recording. As a result, we have an embarrassment of riches – a nearly complete picture

of classical singing as it existed at the turn of the century. Instrumentalists soon would

follow. Irretrievably lost, though, was the cream of the previous generation, whose

artistry had soared while Edison immortalized whistlers and coon songs.

But just how reliable are these artifacts to convey their era? Unfortunately, their value is compromised by severe problems, both artistic and technical.

From a purely artistic

standpoint, the early records do not necessarily represent masters at the height of their

talents. Nowadays, recording is an accepted, if not dominant, activity for all but a

handful of top artists. But at the turn of the century, the experience was not only new,

but daunting and even degrading. Indeed, it is amazing that any reputable musician

recorded at all. Just picture what was involved. An artist accustomed to the lavish caress

of high society would report to a seedy building. In place of the reverberant ambiance of

the concert hall, he was shut up in a closet with harsh acoustics. There was no audience

whose reactions were a necessary source of inspiration. Nor was there room for an

orchestra – just an upright piano. Accustomed to move freely about the stage and to sway

soulfully, our artist was warned to stand rigidly before the recording horn. In place of

subtle dynamic shadings, he was ordered to sound each tone uniformly. And worst of all,

these demands came from a technician who could care nothing about musical art. Nowadays, recording is an accepted, if not dominant, activity for all but a

handful of top artists. But at the turn of the century, the experience was not only new,

but daunting and even degrading. Indeed, it is amazing that any reputable musician

recorded at all. Just picture what was involved. An artist accustomed to the lavish caress

of high society would report to a seedy building. In place of the reverberant ambiance of

the concert hall, he was shut up in a closet with harsh acoustics. There was no audience

whose reactions were a necessary source of inspiration. Nor was there room for an

orchestra – just an upright piano. Accustomed to move freely about the stage and to sway

soulfully, our artist was warned to stand rigidly before the recording horn. In place of

subtle dynamic shadings, he was ordered to sound each tone uniformly. And worst of all,

these demands came from a technician who could care nothing about musical art.

Here is how the great

pianist Ferruccio Busoni described his first encounter with the recording horn:

Yesterday I suffered the

gramophone drudge through to the end! I feel pretty shattered … as if I were awaiting

surgery. … They wanted the Gounod-Liszt Faust-waltz (which lasts a good 10 minutes) –

but only four minutes' worth! – so I quickly had to make cuts, patch and improvise, so

that it still retained its sense; give due regard to the pedal (because it sounds bad),

had to remember that particular notes must be struck louder or softer – to please the

infernal machine; not to let myself go – for the sake of accuracy – and remain conscious

throughout that every note was being preserved for eternity. How can inspiration, freedom,

elan or poetry arise?

And Busoni was far from a

true pioneer; his martyrdom came in 1919, after decades of improvements!

It is hardly surprising

that so many performances from this era are stiff, mechanical and uninspired. The artist

was in alien territory, intimidated if not scared to death; everything he had spent a

lifetime learning had to be altered or ignored. The true wonder is that any genuine

artistry emerged from such trying circumstances. But the musical giants both came and

overcame. Even one of Busoni's seven discs (collected on Pearl 9349) is brilliantly

headstrong and virtuostic. mechanical and uninspired. The artist

was in alien territory, intimidated if not scared to death; everything he had spent a

lifetime learning had to be altered or ignored. The true wonder is that any genuine

artistry emerged from such trying circumstances. But the musical giants both came and

overcame. Even one of Busoni's seven discs (collected on Pearl 9349) is brilliantly

headstrong and virtuostic.

To aggravate the problem

of culture shock, the most enticing records were made by concert veterans at the very end

of long lives of discovery, exploration and development during which their outlooks

constantly evolved and their skills began to dissipate. (In contrast to our present

notions of longevity, abetted by modern medicine, a sixty-year old performer of the last

century was already very old.) The artistry of some survived intact but others' clearly

did not.

Perhaps the most severe

disappointment is a 1926 performance of Beethoven's Symphony # 1 by the Royal

Philharmonic Orchestra led by Sir George Henschel (last available on Past Masters LP

PM-17). The promise of this recording is uniquely compelling. Henschel was a pupil of

Ignaz Moscheles who, in turn, was the devoted assistant of none other than Beethoven

himself! With typical British reserve, Henschel recalled: "On being introduced to

him, I felt a certain sensation of awe on shaking the hand of one who had seen Beethoven

face to face and had been commissioned by the master to prepare the vocal score of Fidelio

[Beethoven's only opera]." Henschel's record is the only one made by a student of a

protege of Beethoven – and in rich, electrical sound, no less! This is the closest link

we have to the most influential composer of all time, whose symphonies remain the

interpretive touchstone for every modern conductor. A reviewer of the time hailed the

record as Henschel's "well known interpretation" and assured readers that

"judging from this recording ... the distinguished conductor is far from impaired in

his powers." Surely, Henschel's way with the music would be authentic. And yet, his

performance is genteel, plodding, and downright boring. How can Henschel's placid

walk-through possibly represent the aesthetic of Beethoven, the rebel who wrenched music

from its complacent classical moorings into a new emotive era and who destroyed pianos

trying to wrest more powerful sounds out of them? If Henschel ever had absorbed

Beethoven's obsessive visceral temperament through Moscheles, then his art clearly did not

survive to his record. The promise of this recording is uniquely compelling. Henschel was a pupil of

Ignaz Moscheles who, in turn, was the devoted assistant of none other than Beethoven

himself! With typical British reserve, Henschel recalled: "On being introduced to

him, I felt a certain sensation of awe on shaking the hand of one who had seen Beethoven

face to face and had been commissioned by the master to prepare the vocal score of Fidelio

[Beethoven's only opera]." Henschel's record is the only one made by a student of a

protege of Beethoven – and in rich, electrical sound, no less! This is the closest link

we have to the most influential composer of all time, whose symphonies remain the

interpretive touchstone for every modern conductor. A reviewer of the time hailed the

record as Henschel's "well known interpretation" and assured readers that

"judging from this recording ... the distinguished conductor is far from impaired in

his powers." Surely, Henschel's way with the music would be authentic. And yet, his

performance is genteel, plodding, and downright boring. How can Henschel's placid

walk-through possibly represent the aesthetic of Beethoven, the rebel who wrenched music

from its complacent classical moorings into a new emotive era and who destroyed pianos

trying to wrest more powerful sounds out of them? If Henschel ever had absorbed

Beethoven's obsessive visceral temperament through Moscheles, then his art clearly did not

survive to his record.

Modern listeners also face

technical challenges. The original records themselves were far from faithful sonic

reproductions. The primitive acoustic recording apparatus successfully captured all of the

fundamentals and most harmonics of the human voice. Instruments, though, were far worse

served, as both their bottom and higher reaches lay well beyond the limit of the

mechanism's mid-range registration.

Preservation compounds the

problem of deficient fidelity. Master material and archival copies of the earliest records

are extremely rare. Most modern transfers necessarily are from copies salvaged by

collectors which had been stored haphazardly and played repeatedly with easily worn

needles using stylus pressures that would slice right through vinyl. These records are

often in dismal condition and fall far off the scale of traditional quality grading

standards. It is amazing that some of these battered survivors can yield any useful sound

at all.

To surmount these

technical hurdles, three fundamental approaches have emerged, each typified by an English

firm specializing in historical reissues. Each involves severe compromises in the elusive

pursuit of authenticity and none is wholly satisfying.

The Pearl label and its

Opal subsidiary take a purist approach. Their philosophy is to forego filtering, scratch

removal and other renovation in order to transfer as much of the original sound as

possible. As commendable as this seems on paper, it is often infuriating in practice. Much

of the source material is in terrible shape, and it can take an enormous mental effort to

weed out the musical information from the aural tangle of surface noise, gouges, cracks,

stripped grooves and other defects that often overwhelm the music. The Pearl/Opal

catalogue of early classical records is by far the most extensive, but don't rush out to

buy an armful of their releases until you've sampled one and have determined that you're

up to the challenge. Their philosophy is to forego filtering, scratch

removal and other renovation in order to transfer as much of the original sound as

possible. As commendable as this seems on paper, it is often infuriating in practice. Much

of the source material is in terrible shape, and it can take an enormous mental effort to

weed out the musical information from the aural tangle of surface noise, gouges, cracks,

stripped grooves and other defects that often overwhelm the music. The Pearl/Opal

catalogue of early classical records is by far the most extensive, but don't rush out to

buy an armful of their releases until you've sampled one and have determined that you're

up to the challenge.

Nimbus takes a far

different tack for its predominantly vocal releases, playing the old discs on "state

of the art" acoustic phonographs in ambient rooms and recording the sound that

emerges from the bell of the horn, so as to approximate the enjoyment of a well-heeled

listener of the time. Although the Nimbus discs have a lovely, smooth sound, detractors

correctly point out that this method accentuates the aural limitations and reinforces the

peculiar resonances of the acoustic process. (Amazingly, Nimbus uses the same technique

for electrical sides, unnecessarily degrading their quality.) Those of us who collect

acoustic 78s know that they contain far more musical information than even the best

apparatus of the time could render. playing the old discs on "state

of the art" acoustic phonographs in ambient rooms and recording the sound that

emerges from the bell of the horn, so as to approximate the enjoyment of a well-heeled

listener of the time. Although the Nimbus discs have a lovely, smooth sound, detractors

correctly point out that this method accentuates the aural limitations and reinforces the

peculiar resonances of the acoustic process. (Amazingly, Nimbus uses the same technique

for electrical sides, unnecessarily degrading their quality.) Those of us who collect

acoustic 78s know that they contain far more musical information than even the best

apparatus of the time could render.

The most intrusive extreme

applies the full gamut of current technology in an effort to enhance the music while

suppressing mechanical defects. In a misguided effort at modernization, though, most

labels seem unable to resist excessive tampering and manage to yield only a falsified,

synthetic sound that is more puerile than pure. As befits a company begun as a labor of

love by a violin maker, Biddulph manages through intelligent restraint to achieve

consistently tasteful and eminently musical results. Some aural flaws remain, but these

are easily ignored by that most sophisticated of all sonic restoration hardware: the human

ear. Unfortunately, the market for early historical releases is small and duplication of

repertoire is economically imprudent. Since Pearl, Nimbus and careless dupers already have

issued the most important early material, Biddulph and other small, exacting firms seem

unlikely to compete with their own superior editions. In a misguided effort at modernization, though, most

labels seem unable to resist excessive tampering and manage to yield only a falsified,

synthetic sound that is more puerile than pure. As befits a company begun as a labor of

love by a violin maker, Biddulph manages through intelligent restraint to achieve

consistently tasteful and eminently musical results. Some aural flaws remain, but these

are easily ignored by that most sophisticated of all sonic restoration hardware: the human

ear. Unfortunately, the market for early historical releases is small and duplication of

repertoire is economically imprudent. Since Pearl, Nimbus and careless dupers already have

issued the most important early material, Biddulph and other small, exacting firms seem

unlikely to compete with their own superior editions.

So, armed with forgiving

ears and bold expectations, what can these ancient messengers tell us of their era?

An instructive digression

is a collection of Edison cylinders or Berliner discs from the late 1800s (as on Symposium

CD 1058), which represent the first budding of the record industry: songs, recitations,

cornet, banjo, clarinet and trombone solos, vocal quartets and band selections (including

some by Sousa's Band). Both the recordings and the performances are typically dreadful.

This is not desert island manna, but hearing such stuff once is essential in order to

place the glories to come in their proper perspective.

The best place to start

exploring the first decade of serious recording is "A Record of Singers" (EMI

RLS 7705 & 7706, 6 LPs each, plus a one-LP supplement). The ambitious goal was to

present at least one example of the art of every famous singer who recorded prior to World

War I, including many who, although then in decline, had been major figures of the last

century. And so we begin with the weird sound of Alessandro Moreschi, the only recorded

castrato (believe me -- you really don't want to know!) and end an exhaustive twelve hours

later with an a capella Russian folk song by a young Feodor Chaliapin (who would

later emerge as the century's greatest bass). The selections are superb and the transfers

are stunning, derived from original metal stampers and the cream of private collections.

The only regret is a lack of explanatory notes beyond bare discographic information, but

Michael Scott's wonderful The Record of Singing (Duckworth, 1977) is intended as a

companion. is "A Record of Singers" (EMI

RLS 7705 & 7706, 6 LPs each, plus a one-LP supplement). The ambitious goal was to

present at least one example of the art of every famous singer who recorded prior to World

War I, including many who, although then in decline, had been major figures of the last

century. And so we begin with the weird sound of Alessandro Moreschi, the only recorded

castrato (believe me -- you really don't want to know!) and end an exhaustive twelve hours

later with an a capella Russian folk song by a young Feodor Chaliapin (who would

later emerge as the century's greatest bass). The selections are superb and the transfers

are stunning, derived from original metal stampers and the cream of private collections.

The only regret is a lack of explanatory notes beyond bare discographic information, but

Michael Scott's wonderful The Record of Singing (Duckworth, 1977) is intended as a

companion.

There are many early vocal

collections on single Pearl, Nimbus and other discs, but "A Record of Singing"

is the set to have and to treasure. Sadly, it is unavailable on CD, but an affordable

alternative is "The Era of Adelina Patti" on Nimbus 7840/1 (2 CDs). Also

worthwhile is Sony's fine restoration on MH2K 62334 of the first American opera series,

recorded by Columbia in 1902-3. Several individual singers, though, command greater

attention.

Adelina Patti — By

far the most important of the past vocal masters to record was Patti (1843 - 1919), the

reigning diva of the second half of the nineteenth century who virtually founded the

florid "coloratura" style still so admired today. Although she reportedly

swooned with delight upon hearing her first playback (destroying the soft wax master in

the process), her records are a mixed success. They are really quite lovely to hear, and

serve as well to preserve for us certain techniques and embellishments that characterized

her art (and, by extension, authentic singing of her generation). And yet, at times she

sounds stiff and breathless; even her most ardent admirers admitted that only a glimmer

remained of the subtlety of her extraordinary art by the time she came to record (1905-6).

But despite the ravages of age, you can't help but thrill at the realization that what you

are really hearing is a performance of the mid-1800s by the most acclaimed vocalist of her

era. Collected on Pearl CD 9312, the authenticity of Patti's performances sweeps aside any

concern over her lapsed powers. the

reigning diva of the second half of the nineteenth century who virtually founded the

florid "coloratura" style still so admired today. Although she reportedly

swooned with delight upon hearing her first playback (destroying the soft wax master in

the process), her records are a mixed success. They are really quite lovely to hear, and

serve as well to preserve for us certain techniques and embellishments that characterized

her art (and, by extension, authentic singing of her generation). And yet, at times she

sounds stiff and breathless; even her most ardent admirers admitted that only a glimmer

remained of the subtlety of her extraordinary art by the time she came to record (1905-6).

But despite the ravages of age, you can't help but thrill at the realization that what you

are really hearing is a performance of the mid-1800s by the most acclaimed vocalist of her

era. Collected on Pearl CD 9312, the authenticity of Patti's performances sweeps aside any

concern over her lapsed powers.

Patti's contributions to

the recording industry were not wholly aesthetic. The most flaming egos of our age pale in

comparison to hers. She commanded up to $5,000 per performance, more than the President of

the United States made in a year; when chided about this, she reportedly challenged the

President to sing as well as she did! She refused to set foot in a studio and made

engineers come to her home; she insisted that her records bear a distinctive pink

"Patti" label; and she set their price at 21 shillings. (That's right – about 3

minutes of music for the modern-day equivalent of $50. And we complain about CD prices?)

Francesco Tamagno —

Patti's business terms may have been severe, but they weren't unique. Tamagno's records,

too, were recorded in his home, had special labels, and cost one pound. But in one

respect, at least, he surpassed even Patti: one of his discs, the "Esultate"

aria from Verdi's Otello, lasts a mere 68 seconds, of which the first 25 are a

piano introduction! That this and his other records sold well, even at their outrageously

inflated price, attests to his fame. Tamagno's records,

too, were recorded in his home, had special labels, and cost one pound. But in one

respect, at least, he surpassed even Patti: one of his discs, the "Esultate"

aria from Verdi's Otello, lasts a mere 68 seconds, of which the first 25 are a

piano introduction! That this and his other records sold well, even at their outrageously

inflated price, attests to his fame.

Tamagno (1850 - 1905) had

been selected by Verdi to create the lead role in the 1887 premiere of Otello. His

bold and hyper-emotional singing of the Otello arias is still startling (he gasps

loudly for breath as he expires!), preserving for all time the performance intended by the

greatest opera composer of his age for the hero of his masterpiece. Unlike Patti, Tamagno

was still in full voice in 1903 when he recorded. All of his recordings, including

outtakes, are on Opal CD 9846.

Mattia Battistini —

Italian music of the 19th century was quintessentially vocal music. Great opera composers

such as Rossini, Bellini and Donizetti emphasized purity, nobility, subtlety and the sheer

beauty of the human voice. With Verdi, though, a new ideal of "verismo" arose in

which drama, emotion and realism supplanted the older style. Although his career came

after the turn to verismo, Battistini (1856 - 1928) focussed his repertoire on the earlier

style and was universally acclaimed by those who had lived through the previous era as one

of its greatest exponents. His records, made from 1902 to 1924, are uniformly beautiful

and, more important, are the fullest evidence we have of the pre-verismo vocal style of

the previous two generations. Selections of Battistini's glorious output are available on

Nimbus 7831 and Pearl 9936, 9946 and 9016. Great opera composers

such as Rossini, Bellini and Donizetti emphasized purity, nobility, subtlety and the sheer

beauty of the human voice. With Verdi, though, a new ideal of "verismo" arose in

which drama, emotion and realism supplanted the older style. Although his career came

after the turn to verismo, Battistini (1856 - 1928) focussed his repertoire on the earlier

style and was universally acclaimed by those who had lived through the previous era as one

of its greatest exponents. His records, made from 1902 to 1924, are uniformly beautiful

and, more important, are the fullest evidence we have of the pre-verismo vocal style of

the previous two generations. Selections of Battistini's glorious output are available on

Nimbus 7831 and Pearl 9936, 9946 and 9016.

Enrico Caruso — Fancy

labels and other trivia aside, Caruso (1873 - 1921) was the first, and perhaps the

greatest, superstar of the record industry. Beginning in 1902 he recorded prolifically,

and his lifetime royalties were said to have exceeded two million dollars. But as with a

certain King of more recent memory, Caruso's death in 1921 was more an inconvenience than

an end; RCA was still issuing "new" Caruso records well into the 1930's by

dubbing his voice onto fresh orchestral tracks! Caruso (1873 - 1921) was the first, and perhaps the

greatest, superstar of the record industry. Beginning in 1902 he recorded prolifically,

and his lifetime royalties were said to have exceeded two million dollars. But as with a

certain King of more recent memory, Caruso's death in 1921 was more an inconvenience than

an end; RCA was still issuing "new" Caruso records well into the 1930's by

dubbing his voice onto fresh orchestral tracks!

The torrent of Caruso

single reissues, LP compilations and now CD collections has never let up, and with good

reason. The tone of Caruso's huge, ringing voice was beautifully captured by acoustic

recording and reproduced magnificently. Even today, his records still sound marvelous. And

Caruso could sing anything well, from highly ornamented Handel to impassioned neapolitan

songs – even a rousing rendition of George M. Cohan's "Over There." As Michael

Scott explains it in terms of musical traditions, Caruso's art embraced both the

nineteenth and twentieth centuries, as his technique was founded in the skills of the old

style, but with unprecedented tension and power that were thoroughly modern. Even today, his records still sound marvelous. And

Caruso could sing anything well, from highly ornamented Handel to impassioned neapolitan

songs – even a rousing rendition of George M. Cohan's "Over There." As Michael

Scott explains it in terms of musical traditions, Caruso's art embraced both the

nineteenth and twentieth centuries, as his technique was founded in the skills of the old

style, but with unprecedented tension and power that were thoroughly modern.

Caruso's complete output

is available on 12-CD sets from RCA (60445-2-RG) and Pearl (in four 3-CD volumes, EVC I,

II, III and IV). Good collections are available on numerous single discs from RCA, Pearl

and Nimbus. Unless you truly hate singing altogether, you just have to love Caruso. And

through him you can relive an era of bold personality which serves, rather than supplants,

the music. But Caruso's true immortality transcends even RCA's marketing prowess, as his

style has been imitated and adopted by nearly every tenor since. Much the same can be said

for Patti and Tamagno, whose art survives in the skill of nearly all the sopranos and

heroic tenors on stage today. As a result, nowadays their pioneering work may seem more

familiar than enlightening and so we must turn elsewhere on our quest to illuminate the

past.

Except as vocal

accompaniment, few instrumentalists recorded at all at the dawn of the twentieth century.

Of those who did, many were young prodigies whose stylistic roots did not extend very deep

into the past.

Among available

compilations, "The Recorded Violin" (Pearl BVA I and II, two 3-CD volumes) is

conceived along lines similar to "A Record of Singers" and is second only to

that achievement in its scope. Among the violinists included are many who were active in

the 1800s and who shaped or reflected the ideals of their time. A fine single-disc survey

of the most venerable pioneers is on Symposium 1071. A astute sampler is Opal CD 9851,

which combines the complete recordings of Joseph Joachim (1831 - 1907), the exemplar of

German tradition, with those of Pablo de Sarasate (1844 - 1908), the preeminent

pyrotechnic virtuoso of the glitzy French school, and five sides by the great expressive

Belgian violinist Eugene Ysaye (1858 - 1931), whose complete work has just been issued in

fabulous sound on Sony MHK 62337. "The Recorded Violin" (Pearl BVA I and II, two 3-CD volumes) is

conceived along lines similar to "A Record of Singers" and is second only to

that achievement in its scope. Among the violinists included are many who were active in

the 1800s and who shaped or reflected the ideals of their time. A fine single-disc survey

of the most venerable pioneers is on Symposium 1071. A astute sampler is Opal CD 9851,

which combines the complete recordings of Joseph Joachim (1831 - 1907), the exemplar of

German tradition, with those of Pablo de Sarasate (1844 - 1908), the preeminent

pyrotechnic virtuoso of the glitzy French school, and five sides by the great expressive

Belgian violinist Eugene Ysaye (1858 - 1931), whose complete work has just been issued in

fabulous sound on Sony MHK 62337.

"The Recorded

Cello" (Pearl CDS 9981-3 and 9984-6, 3 CDs each) is a companion to the violin set.

But Pearl's transfers here are especially rough and the nineteenth century cellists prove

to be an awfully strait-laced group from whom little style can be gleaned, as distinctive

personality only emerged with Pablo Casals (1876 - 1973). "The Recorded Viola"

(Pearl CDS 9148, 9149 and 9150, 2 CDs each) affords even less insight, as it begins with

the twentieth century revival wrought by Oskar Nedbal and Lionel Tertis (both born in

1876) and tells us little of their predecessors.

Curiously, there has been

no survey of early pianism, despite the huge number of fine examples recorded by

acknowledged masters. The first were cut by the great French pianist Raoul Pugno in 1903,

whose bold personality and exquisite passagework are still amazing to hear. (Actually,

Pugno had been preceded in 1899 by Alfred Grünfeld, but his first recordings were mostly

precious salon stuff; his artistry emerged only in later discs, collected on Opal CD

9850.) Pugno's twenty sides, (on Opal CD 9386) are all robust, magnificently played and

bursting with character. But they are barely listenable, having been cut on a seriously

defective turntable with wildly fluctuating speed. Surely modern computers could correct

this, but the purists at Pearl apparently wouldn't even think of such a thing. If nothing

else, though, you may want this CD on hand for the next time a non-hi fi friend questions

the point of wow and flutter measurements in analog equipment reviews.

Pugno was born in 1852. To

Vladimir de Pachmann (1848 - 1933) falls the distinction of being the most famed pianist

on record who was born in the first half of the nineteenth century. De Pachmann was

reputed to be an extremely sensitive artist and the greatest Chopin player of his time.

But by the time he came to record he was known as the "Chopinzee," as antic

eccentricities (weird dress, fussing with the piano stool, lecturing the audience and

outrageous interview statements) had all but eclipsed his former talent. Opal CD 9840

contains nineteen of de Pachmann's records; some are awfully sloppy, but others display

exquisite delicacy and successfully invoke his former wonder. Included is a bizarre

curiosity: a riotous take of a Chopin Etude through which de Pachmann babbles

incessantly and after flubbing the ending protests: "Godowsky [his arch-rival] was

the author!" falls the distinction of being the most famed pianist

on record who was born in the first half of the nineteenth century. De Pachmann was

reputed to be an extremely sensitive artist and the greatest Chopin player of his time.

But by the time he came to record he was known as the "Chopinzee," as antic

eccentricities (weird dress, fussing with the piano stool, lecturing the audience and

outrageous interview statements) had all but eclipsed his former talent. Opal CD 9840

contains nineteen of de Pachmann's records; some are awfully sloppy, but others display

exquisite delicacy and successfully invoke his former wonder. Included is a bizarre

curiosity: a riotous take of a Chopin Etude through which de Pachmann babbles

incessantly and after flubbing the ending protests: "Godowsky [his arch-rival] was

the author!"

Of other pianists born

before 1850, the recorded evidence is mostly inconclusive. The oldest was the versatile

composer Camille Saint-Saens (1835 - 1921), whose only disc in circulation is vocal

accompaniment from which little can be inferred. Francis Planté (1839 - 1934) waited to

record until he was ninety, by which time the delicacy and nuance for which he was known

had all but vanished; his ten discs are on Opal CD 9857. The records of Louis Diémer

(1843 - 1919) eluded LP or CD transfer. The nine sides cut in May 1903 by pianist/composer

Edward Grieg (1843 - 1907) emphasize the strength and dignity he sought in the performance

of his own works but do not imply a more general style; two of his sides are on Pearl CD

9933 and all are on Simax PSC 1809 (3 CDs).

Speaking of venerable

keyboardists, we should not overlook the "King of Instruments" or Charles-Marie

Widor (1844 - 1937), who recorded his scintillating organ Toccata (on EMI CD

55037). It would be unkind, though, to say more of his labored performance, other than to

note that he was 88 at the time.

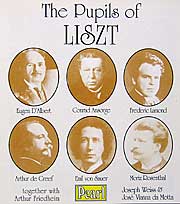

Nearly every other great

pianist in the concert halls at the end of the nineteenth century (and in the recording

studios at the beginning of the twentieth) had been a pupil of either Franz Liszt or

Theodor Leschetizky. But both emphasized developing a performer's individuality, and so

there is really no consistent manner among their students. Thus, the recordings of Liszt's

own First Piano Concerto by his pupils Emil van Sauer (Pearl CD 9403) and Arthur de

Greef (Opal 829, LP only) sound strikingly different. Similarly, the graduates of the

Leschetizky method, such as it was, included such divergent stylists as Ignaz Friedman,

whose reputation tended toward headstrong, thundering virtuosity, Ignaz Paderewski, whose

immense popularity owed as much to his politics and charisma (not to mention his abundant

hair) than his flawed but deeply poetic playing, and Artur Schnabel, whose cool, cerebral

readings of Mozart, Schubert and especially Beethoven went far toward molding our modern

taste. (and in the recording

studios at the beginning of the twentieth) had been a pupil of either Franz Liszt or

Theodor Leschetizky. But both emphasized developing a performer's individuality, and so

there is really no consistent manner among their students. Thus, the recordings of Liszt's

own First Piano Concerto by his pupils Emil van Sauer (Pearl CD 9403) and Arthur de

Greef (Opal 829, LP only) sound strikingly different. Similarly, the graduates of the

Leschetizky method, such as it was, included such divergent stylists as Ignaz Friedman,

whose reputation tended toward headstrong, thundering virtuosity, Ignaz Paderewski, whose

immense popularity owed as much to his politics and charisma (not to mention his abundant

hair) than his flawed but deeply poetic playing, and Artur Schnabel, whose cool, cerebral

readings of Mozart, Schubert and especially Beethoven went far toward molding our modern

taste.

A fascinating

cross-section of pianism is found on "Pupils of Leschetizky" (Opal CD 9839) and

"Pupils of Liszt" (Pearl 9972, 2 CDs). But while these collections amply attest

to the students' highly individual personalities, they tell us little of the style of

their teachers, who set the aesthetic of their time but whose self-effacing methods

refused to mold their pupils into mimicry.

So how did the nineteenth

century masters themselves play? We have no direct evidence. Liszt died in 1886.

Leschetizky lived until 1915 but cut only piano rolls (one, a Chopin Nocturne, is

on Opal CD 9839), which were often enhanced after the fact and tell little of a pianist's

tone or quality; Leschetizky's is stiff and opaque. And yet, we do have a remarkable set

of blueprints, albeit indirect ones.

Liszt was not only one of

the greatest teachers of his century, but was also one of the two most influential

performers, a supreme virtuoso who revolutionized the keyboard with his bombastic playing.

He was also considered the greatest improviser of all time, unable to resist recomposing

even a new score as he sight-read it for the very first time. The most extraordinary

evidence of Lisztian playing arose nearly a century after his death in a most unlikely

guise. Ervin Nyiregyhazi, born in Budapest in 1903, became enthralled and obsessed with

Liszt. Those who had known the master lauded the teenager as his spiritual heir. But after

a series of brilliant debuts and ecstatic reviews of his mesmerizing playing, Nyiregyhazi

dropped out of sight. Fifty years and nine marriages later he resurfaced in 1973 in a Los

Angeles flophouse. Having barely touched a keyboard in decades, he was coaxed into a

recital in a local church, part of which (two Liszt "Legendes") was taped on a

cheap cassette deck. Issued on Desmar LP IPA 111, this is one of the most intense

performances ever recorded, with a power and a spirituality beyond anything else in the

realm of modern experience. Following his rediscovery, Nyiregyhazi went on to became a

critical darling and cut several studio albums, but none approached what he had achieved

in that one astounding concert in which he resurrected the spirit of Liszt just once in

our time. a supreme virtuoso who revolutionized the keyboard with his bombastic playing.

He was also considered the greatest improviser of all time, unable to resist recomposing

even a new score as he sight-read it for the very first time. The most extraordinary

evidence of Lisztian playing arose nearly a century after his death in a most unlikely

guise. Ervin Nyiregyhazi, born in Budapest in 1903, became enthralled and obsessed with

Liszt. Those who had known the master lauded the teenager as his spiritual heir. But after

a series of brilliant debuts and ecstatic reviews of his mesmerizing playing, Nyiregyhazi

dropped out of sight. Fifty years and nine marriages later he resurfaced in 1973 in a Los

Angeles flophouse. Having barely touched a keyboard in decades, he was coaxed into a

recital in a local church, part of which (two Liszt "Legendes") was taped on a

cheap cassette deck. Issued on Desmar LP IPA 111, this is one of the most intense

performances ever recorded, with a power and a spirituality beyond anything else in the

realm of modern experience. Following his rediscovery, Nyiregyhazi went on to became a

critical darling and cut several studio albums, but none approached what he had achieved

in that one astounding concert in which he resurrected the spirit of Liszt just once in

our time.

The other most influential

pianist of the nineteenth century was Chopin, whose exquisite subtlety was a world apart

from Liszt's unbridled energy. Chopin died in 1849 and none of his students lived to

record. And yet, a reliable trace of his style also exists in our century. Chopin's

foremost pupil was Karl Mikuli, who devoted his life to teaching his master's approach to

his works. One of Mikuli's pupils, Raoul Koczalski, was highly unusual in that he was a

prodigy of such a high order that after studying with Mikuli he had no need of further

teachers. Thus, having absorbed Chopin through Mikuli, he remained relatively immune from

other influences. His records, collected on Pearl CD 9472, are as close as we will ever

get to Chopin himself. They exemplify the composer's reputed rhythmic freedom, contain

many ornaments not in the scores and reflect outmoded practices (such as having one hand

slightly lead the other), all of which we must presume are authentic. whose exquisite subtlety was a world apart

from Liszt's unbridled energy. Chopin died in 1849 and none of his students lived to

record. And yet, a reliable trace of his style also exists in our century. Chopin's

foremost pupil was Karl Mikuli, who devoted his life to teaching his master's approach to

his works. One of Mikuli's pupils, Raoul Koczalski, was highly unusual in that he was a

prodigy of such a high order that after studying with Mikuli he had no need of further

teachers. Thus, having absorbed Chopin through Mikuli, he remained relatively immune from

other influences. His records, collected on Pearl CD 9472, are as close as we will ever

get to Chopin himself. They exemplify the composer's reputed rhythmic freedom, contain

many ornaments not in the scores and reflect outmoded practices (such as having one hand

slightly lead the other), all of which we must presume are authentic.

There is one more set of

20th century piano recordings which provides a tantalizing link to the past: 1928-30

performances of several Schumann piano works, including his Concerto, by Fanny

Davies (Pearl CD 9291). Davies was one of the last pupils of Clara Schumann, who was not

only a famous virtuoso in her own right but also the widow of the great composer. For

forty years following Robert's death in 1856, Clara devoted herself to perpetuating her

husband's way of performing his music (much of which she had inspired), insisting that her

pupils observe her detailed instructions exactly, just as she had absorbed them from

Robert in the 1830s. Thus Davies's earnest but relaxed elegance and unusual phrasing are

presumably those of the composer himself and transport us back nearly a full century

before her records were made. Yet despite his romantic temperament and critical writing,

Schumann set few stylistic trends in his day, and so Davies's performances remain more a

lovely footnote than a guiding beacon to the sonic ideals of a lost age. which provides a tantalizing link to the past: 1928-30

performances of several Schumann piano works, including his Concerto, by Fanny

Davies (Pearl CD 9291). Davies was one of the last pupils of Clara Schumann, who was not

only a famous virtuoso in her own right but also the widow of the great composer. For

forty years following Robert's death in 1856, Clara devoted herself to perpetuating her

husband's way of performing his music (much of which she had inspired), insisting that her

pupils observe her detailed instructions exactly, just as she had absorbed them from

Robert in the 1830s. Thus Davies's earnest but relaxed elegance and unusual phrasing are

presumably those of the composer himself and transport us back nearly a full century

before her records were made. Yet despite his romantic temperament and critical writing,

Schumann set few stylistic trends in his day, and so Davies's performances remain more a

lovely footnote than a guiding beacon to the sonic ideals of a lost age.

Recordings of symphonic

orchestras (as opposed to brass bands) were quite rare prior to 1920. The acoustic

apparatus simply couldn't register the highest and lowest two octaves of orchestral sound.

Without upper harmonics, the tonal color became blurred and the distinctive timbres of

strings, brass and winds sounded confusingly similar. Double basses, which give the

orchestra its sonic anchor, reproduced only as an overtonal whine and were routinely

replaced by tubas, whose more flatulent tone registered quite well. Beyond sonic

limitations, there was the sheer logistical problem of cramming even reduced forces into a

room sufficiently small to capture their sound; indeed, not until 1917 in Boston was a

full orchestra pickup even attempted. The acoustic

apparatus simply couldn't register the highest and lowest two octaves of orchestral sound.

Without upper harmonics, the tonal color became blurred and the distinctive timbres of

strings, brass and winds sounded confusingly similar. Double basses, which give the

orchestra its sonic anchor, reproduced only as an overtonal whine and were routinely

replaced by tubas, whose more flatulent tone registered quite well. Beyond sonic

limitations, there was the sheer logistical problem of cramming even reduced forces into a

room sufficiently small to capture their sound; indeed, not until 1917 in Boston was a

full orchestra pickup even attempted.

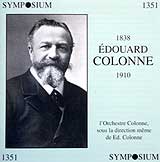

The few early orchestral

recordings were dominated by young conductors such as Thomas Beecham, Ernest Ansermet,

Frederick Stock and Leopold Stokowski, who generally sought an independent stylistic

course from their predecessors. The first conductor with a solid reputation to have made records is Edouard Colonne (1838 – 1910), who had been trained and became active a full generation before any of the others. With his Orchestre Colonne (an immodest but common naming practice of the time) he cut 20 sides for Pathé in 1906. Long unavailable, all are assembled on Symposium CD 1351 in wonderful transfers, revealing surprisingly detailed sound that fluently surmounts the technological hurdles of its time with broad dynamic range, effectively spotlighted solos, atmospheric depth, vivid chord voicing and a wide variety of textures that even include credible cymbal nuances. Although Colonne’s leadership was reputed more for inspiration than precision, the performances themselves are delightful and fully as striking as the sonics, with excellent execution, rhythmic acuity, carefully paced volume swells, gracious phrasing and sharp sforzandos, leaving an overall impression of elegance, finely balancing power and grace, intensity and warmth, focus and spirit. Even the rare moments of slack ensemble seem more a reflection of the musicians’ zeal and humanity than a regrettable lapse. such as Thomas Beecham, Ernest Ansermet,

Frederick Stock and Leopold Stokowski, who generally sought an independent stylistic

course from their predecessors. The first conductor with a solid reputation to have made records is Edouard Colonne (1838 – 1910), who had been trained and became active a full generation before any of the others. With his Orchestre Colonne (an immodest but common naming practice of the time) he cut 20 sides for Pathé in 1906. Long unavailable, all are assembled on Symposium CD 1351 in wonderful transfers, revealing surprisingly detailed sound that fluently surmounts the technological hurdles of its time with broad dynamic range, effectively spotlighted solos, atmospheric depth, vivid chord voicing and a wide variety of textures that even include credible cymbal nuances. Although Colonne’s leadership was reputed more for inspiration than precision, the performances themselves are delightful and fully as striking as the sonics, with excellent execution, rhythmic acuity, carefully paced volume swells, gracious phrasing and sharp sforzandos, leaving an overall impression of elegance, finely balancing power and grace, intensity and warmth, focus and spirit. Even the rare moments of slack ensemble seem more a reflection of the musicians’ zeal and humanity than a regrettable lapse.

The only giant among

romantic conductors whose work is preserved is Artur Nikisch (1855 - 1922), who was known

for his luminous orchestral sound (which the discs of the time barely suggest) and a

free-wheeling approach to interpretation (which the records convey quite well). Nikisch's

first and most famous recording was of Beethoven's Fifth Symphony (1913). This was

only the second set to be made of a full-length work, as short pieces and single

movements, often drastically abridged, were previously deemed sufficient to sate the

limits of listener interest. Beyond its historical importance, this performance displays

lovely phrasing and excellent dynamic control and balance (very difficult to achieve with

the acoustic process). It also exhibits Nikisch's famed ability to pursue impulse without

violating the demands of the structure. His talent is confirmed by a 1914 reading of

Liszt's First Hungarian Rhapsody, which begins with haunting atmosphere and then

explodes into crackling excitement. These and the remaining Nikisch sides are collected on

Symposium 1087/8. They surmount their technological limitations to suggest an awesome

degree of headstrong individuality rarely heard in our time. who was known

for his luminous orchestral sound (which the discs of the time barely suggest) and a

free-wheeling approach to interpretation (which the records convey quite well). Nikisch's

first and most famous recording was of Beethoven's Fifth Symphony (1913). This was

only the second set to be made of a full-length work, as short pieces and single

movements, often drastically abridged, were previously deemed sufficient to sate the

limits of listener interest. Beyond its historical importance, this performance displays

lovely phrasing and excellent dynamic control and balance (very difficult to achieve with

the acoustic process). It also exhibits Nikisch's famed ability to pursue impulse without

violating the demands of the structure. His talent is confirmed by a 1914 reading of

Liszt's First Hungarian Rhapsody, which begins with haunting atmosphere and then

explodes into crackling excitement. These and the remaining Nikisch sides are collected on

Symposium 1087/8. They surmount their technological limitations to suggest an awesome

degree of headstrong individuality rarely heard in our time.

As with the pianists, the

most impressive, if indirect, evidence of Nikisch's art may rest with one of his students. Wilhelm Furtwängler (1886 - 1954) idolized Nikisch and succeeded to Nikisch's posts upon

his death. Although Furtwängler's studio recordings are often stolid, his concerts

aroused the same ecstatic emotions as Nikisch's. Many were recorded and remain among the

most exciting examples ever captured of the way in which a brilliant interpretation can

revitalize an oft-heard score. Listening to Furtwängler's riveting accounts of the

Beethoven Ninth Symphony (Music & Arts CD 653), the Bruckner Ninth Symphony

(Music & Arts CD 730) or the Brahms Symphonies (Music & Arts set 941 or

super-budget Virtuoso 2699072) transports us back to the heart and soul of the last

century. But beware -- this is dangerous stuff: once you hear Furtwängler, it's hard to

return to the bland precision that passes for musical interpretation nowadays.

Furtwängler lived and breathed his music.

Wilhelm Furtwängler (1886 - 1954) idolized Nikisch and succeeded to Nikisch's posts upon

his death. Although Furtwängler's studio recordings are often stolid, his concerts

aroused the same ecstatic emotions as Nikisch's. Many were recorded and remain among the

most exciting examples ever captured of the way in which a brilliant interpretation can

revitalize an oft-heard score. Listening to Furtwängler's riveting accounts of the

Beethoven Ninth Symphony (Music & Arts CD 653), the Bruckner Ninth Symphony

(Music & Arts CD 730) or the Brahms Symphonies (Music & Arts set 941 or

super-budget Virtuoso 2699072) transports us back to the heart and soul of the last

century. But beware -- this is dangerous stuff: once you hear Furtwängler, it's hard to

return to the bland precision that passes for musical interpretation nowadays.

Furtwängler lived and breathed his music.

The other indisputably

great and influential late-nineteenth century conductor, Gustav Mahler, died in 1911.

Although he left no orchestral recordings to attest to his conducting style, he did cut

four piano rolls in 1905, now collected on Golden Legacy CD 101. Fortunately, they were

made in the new Welte-Mignon process, which recorded both the notes and their dynamics so

that the playback unit, coupled to a concert grand, reproduced the feel and quality of the

playing in a way which eluded standard rolls. Although interpretive extremes are far

easier to achieve solo than with a full orchestra, Mahler's highly impulsive rolls suggest

his reputed intensity on the podium. Gustav Mahler, died in 1911.

Although he left no orchestral recordings to attest to his conducting style, he did cut

four piano rolls in 1905, now collected on Golden Legacy CD 101. Fortunately, they were

made in the new Welte-Mignon process, which recorded both the notes and their dynamics so

that the playback unit, coupled to a concert grand, reproduced the feel and quality of the

playing in a way which eluded standard rolls. Although interpretive extremes are far

easier to achieve solo than with a full orchestra, Mahler's highly impulsive rolls suggest

his reputed intensity on the podium.

Further glimmers of

Mahler's style appear in early recordings of his compositions by a trio of his disciples.

Mahler's foremost protege, Bruno Walter, lived into the stereo era and is remembered

mostly for his genial, humanistic late Columbia records which, while certainly enjoyable

on their own terms, seem worlds apart from the driven angst of Mahler's piano rolls. In

the late 1930s, though, Walter recorded biting Vienna concerts of Mahler's last symphony

and final song cycle, Das Lied von der Erde (on EMI CD CDH 7 63029 2 and Pearl CD

9413 respectively), of which he had given the world premieres following Mahler's death.

Similar intensity is displayed by Oscar Fried, who waxed a wild 1924 acoustic account of

Mahler's Symphony # 2 (on Pearl CDS 9929), and Willem Mengelberg, who left us a

stunning 1940 concert of the Symphony # 4 (on Philips CD 426 108 2). All throb with

individualistic touches of the same type in which Mahler reportedly indulged in his own

performances.

So what can we make of all

this? To which single artist can we best turn for an entree to the past which can then

deepen our understanding of the present? The beauty of Battistini? The boldness of Caruso?

The poetry of Chopin? The mysticism of Liszt? The impulse of Nikisch? None can serve as an

exclusive paradigm. Classical music, after all, is not monolithic; its artists have always

embraced a wide gamut of styles, personalities and approaches. Perhaps the only valid

impression to be gleaned from the records of the authentic exponents of the last century

is that of diversity itself.

To return to our initial

thought, can any of these be deemed more important than the rest to represent the romantic

era and to illumine our own? Not really, since each has spawned an interpretive style

familiar in our own time. While historically significant, none really tells us much more

about music or performance than we already know from contemporary concerts and records.

And yet there is

something else out there that lies even deeper than these well-explored roots of our

modern age.

In our days of countless

multinational stars, it is hard to appreciate the unique importance of Joseph Joachim. He

was, quite simply, the violinist of the century, intimate friend of Mendelssohn, Schumann,

Liszt and Brahms and considered the supreme interpreter of their works (many of which,

including the violin concerti of Brahms, Bruch and Dvorak, were dedicated to him). From

the very start of his career in 1844, he and his pupils inspired and taught nearly every

great violinist for decades to come. More than anyone else, Joachim defined classical

performance in his time. He

was, quite simply, the violinist of the century, intimate friend of Mendelssohn, Schumann,

Liszt and Brahms and considered the supreme interpreter of their works (many of which,

including the violin concerti of Brahms, Bruch and Dvorak, were dedicated to him). From

the very start of his career in 1844, he and his pupils inspired and taught nearly every

great violinist for decades to come. More than anyone else, Joachim defined classical

performance in his time.

In 1903, near the very end

of his long and remarkable life, Joachim recorded a total of five sides: a trifle of his

own, two solo pieces of Bach and two Brahms Hungarian Dances. As heard on Opal 9851, all

are fascinating; the Hungarian Dance # 2 in d minor, though, is a revelation.

Upon first hearing, the

impression of this record is pathetic: imprecise notes, sloppy bowing, shaky rhythm,

coarse tone. Historical curiosity aside, surely this seems the misjudged ego-trip of a

decrepit man no longer in control of his instrument, his former technique ravaged beyond

all recognition and worsened still by the horrors of the recording experience.

But that's not it at all.

The only thing "wrong" with this performance is that we hear it through modern

ears, ears accustomed to the note-perfect sterility of twentieth century musicianship in

which any departure from the holy text of the written score is an unpardonable artistic

sin.

Of all the thousands upon

thousands of old acoustic records, this one confronts us with a unique challenge. Here is

a style of playing absolutely unknown in our time. Every note bursts with passion. Every

gesture throbs with meaning.

Joachim doesn't sharpen or

flatten certain notes because he can't reach them, but rather to emphasize the force of a

melodic progression or to shade the impact of a chord; indeed, his fingering is so fluid

that the individual notes of his passagework are barely apparent. His rhythm is so

constantly dynamic and alive that it belies the very notion of tempo. And his bowing –

the first downbeats slash with splintering force and soon subside into a whisper.

Joachim tears the notes

right off the page. After hearing this astounding performance, no classical artist should

ever feel embarrassed to play the romantic repertoire with the same unfettered passion as

a hard rocker.

But by what right does any

musician so brutally distort the written score? Joachim undoubtedly would insist that this

is not only the right but the duty of the true artist, who forms a team with the composer.

The score is always a mere starting point, and never the finish line, for valid musical

expression.

To regard written music as

a complete record of a composer's intentions is strictly a twentieth century notion. All

earlier composers knew that performers of their time were immersed in the knowledge of how

to breathe life into the cold written notation. There simply was no need to clutter a

score with directions that any trained musician would assume as a matter of course. Even

Toscanini, the purist whose solution to every interpretive problem was to consult the

score, proclaimed that a true musician had to read between the notes.

Our modern outlook leads

us to forget the vital importance of interpretative freedom in the performance of all

music – including classical. We expect blues, rock, jazz and pop artists to actively

recreate the pieces they perform. We are intrigued to hear two takes by Robert Johnson

that barely sound like the same song, much less the one from which it was derived. We

readily accept Bob Dylan's constant reinventions of his earlier work. We laud Louis

Armstrong and his legions of successors for their creative transformations of melody,

harmony and structure. We salute the brilliance of Elvis and the Sun gang for wresting

their first rockabilly sides out of old country standards. And yet, let a modern classical

musician alter a single marking in the score and he is condemned for placing a swollen and

arrogant ego above the calling of his art.

This attitude is absurd.

All great classical performers of past centuries were prized for their skill at

improvisation. One of the staples of early nineteenth century concerts was the performer's

extemporizing an entire piece, often from a fragment given on the spot by the audience.

Indeed, Beethoven's Piano Fantasia in g minor, Op. 77 is believed to be a

transcription of one of his concert improvisations, taken down "live" in music

shorthand. Any self-respecting soloist of the time was expected to provide his own cadenza

(an extended solo display section toward the end of a movement) in any concerto he

performed.

By these valid historical

standards, our few twentieth century iconoclasts seem rather mild. So what if

Furtwangler's tempos tended toward extremes? Or if Stokowski's early electrical records

wallowed in overripe bass? Or if Glenn Gould galloped breathlessly through Beethoven's "Moonlight"

Sonata? Or if Bernstein distended adagios to a near halt? For that matter, what's

wrong with adaptations of the classics played by Emerson Lake & Palmer or on a Moog

synthesizer? The conventional assumptions of so much of what we have come to accept as

modern musical taste are not only dull; they are just plain wrong.

Edison, though, was right:

the true value of the phonograph does indeed lie beyond mere entertainment. While every

other performance and lesson of his life has long since faded into legend, Joachim's

immortality lies etched in the groove of his ancient record. At the very dawn of our

century, he braved the demon of the acoustic horn and distilled the wisdom of a vanishing

age into a mere three minutes. His supremely precious legacy transcends words and memories

to directly preserve for all time the outlook of the greatest artist of an entire era

which, more than any other, gave rise to the soul of our own. At the very dawn of our

century, he braved the demon of the acoustic horn and distilled the wisdom of a vanishing

age into a mere three minutes. His supremely precious legacy transcends words and memories

to directly preserve for all time the outlook of the greatest artist of an entire era

which, more than any other, gave rise to the soul of our own.

While scholars,

performers, critics and audiences may forever debate the "proper" way to perform

classical music, the evidence of Joachim's record just may be worth more than all the

academic speculation and literature put together. It validates and unifies the huge and

bewildering range of styles presented by the other surviving records of the era. It opens

a crucial door to an understanding of classical music, and perhaps to all music of the

past, that might otherwise have remained forever shut and, in so doing, immeasurably

deepens our grasp of the present.

More important still, it

provides an urgent key to the future. Those who prematurely mourn the death of the

classics should instead heed Joachim's clarion call. In that one brief moment so many

years ago Joachim told us as much as we will ever need to know about the essence of all

music: any performance is "correct" if it stems from commitment, wisdom and

passion.

No more important record

has ever been made.

The historical facts in

this article are derived largely from four well-researched, informative and highly

readable books: Roland Gellatt's The Fabulous Phonograph (MacMillan, 1977), Michael

Scott's Record of Singing (Duckworth, 1977) and Harold Schonberg's The Great

Pianists (Simon & Schuster, 1963) and The Great Conductors (Simon &

Schuster, 1967). By all means, read them; but listen to the music.

Copyright 1997 by

Peter Gutmann

|