|

The past century has seen an unprecedented acceleration of social change – and with it a dwindling of esthetic sensitivity. As a result, nearly all works of art that were deemed shocking or even bold in their time have retained barely a shred of their former power and now seem historical relics rather than genuine jolts. One of the very few exceptions is Richard Strauss's 1905 Salome.

![]() The

tale of Salome began two millennia ago.

The

tale of Salome began two millennia ago.

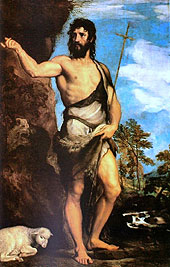

Titian: St. John the Baptist |

The earliest accounts differ in a key detail as to the cause for John's demise. The Jewish historian Josephus reported in his Antiquities of the Jews that Herod the Tetrarch (the regional Roman ruler of Galilee), fearing that John's growing influence might foment a rebellion, had him imprisoned and then put to death. (Although written c. 94 AD, the oldest copy of the Josephus manuscript dates only to the 11th century, yet scholars tend to credit its authenticity despite ample opportunities for revision by dozens of generations of editors.) Josephus adds a further cogent detail – that Herod's brother (known as Herod the Great) and his wife Herodias had a daughter and that shortly after the birth Herodias "taking it into her head to flout the way of our fathers, married Herod the Tetrarch, her husband's brother by the same father, who was tetrarch of Galilee; to do this she parted from a living husband," a severe sin at the time.

Biblical accounts link these two seemingly disparate strands to provide a more personal motive for John's death. According to the Gospels of Matthew and Mark, Herodias wanted to kill John because he condemned her incestuous remarriage, but Herod the Tetrarch protected John as a holy man and simply had him imprisoned. Then, as recounted in the flowing text of the King James version (Mark 6: 21-28):

Herod [the Tetrarch] on his birthday made a supper to his lords, high captains, and chief estates of Galilee; And when the daughter of … Herodias came in, and danced, and pleased Herod and them that sat with him, the king said unto the damsel, "Ask of me whatsoever thou wilt, and I will give it thee." … And she went forth, and said unto her mother, "What shall I ask?" And she said, "The head of John the Baptist." And she came in straightway with haste unto the king, and asked, saying, "I will that thou give me by and by in a charger [i.e., on a platter] the head of John the Baptist." And the king was exceeding sorry; yet for his oath's sake, and for their sakes which sat with him, he would not reject her. And immediately the king sent an executioner, and commanded his head to be brought: and he went and beheaded him in the prison, and brought his head in a charger, and gave it to the damsel: and the damsel gave it to her mother.The Gospels do not name Herodias's daughter, but Josephus does – Salome.

![]() Despite the brevity and detachment of its narrative, the

Biblical tale infers a tantalizing glut of salacious passion – revenge! lust!

corruption! blood! remorse! – none of which was lost on artists (or their

patrons) who could indulge and portray these wicked fantasies in the guise

of devotion to a sacred text. Indeed it became a favorite subject of Italian

Renaissance painters, albeit in the idealized, ornamental style of the time.

Consider, for example, the rich sheen and repressed expressions in the

early 16th Century painting by Bernardino Luini (in the Boston Museum of

Fine Arts),

Despite the brevity and detachment of its narrative, the

Biblical tale infers a tantalizing glut of salacious passion – revenge! lust!

corruption! blood! remorse! – none of which was lost on artists (or their

patrons) who could indulge and portray these wicked fantasies in the guise

of devotion to a sacred text. Indeed it became a favorite subject of Italian

Renaissance painters, albeit in the idealized, ornamental style of the time.

Consider, for example, the rich sheen and repressed expressions in the

early 16th Century painting by Bernardino Luini (in the Boston Museum of

Fine Arts),

Luini: Salome Receiving the Head of St. John the Baptist |

Gozzoli: The Dance of Salome |

A parallel trend of embroidering the simple tale emerged in the literature of the late 19th Century. Many authors added elements of fantasy that enhanced the legend and would wend their way into its most prominent operatic version. Perhaps the most elaborate arose in Joris-Karl Huysman's 1884 A Rebours (Against the Grain / Against Nature), in which the protagonist purchases both Moreau works and rhapsodizes at great length over their splendor, conjuring intricate psychic, and unabashedly erotic, images. Indeed, the language itself throbs with unbridled passion. Consider:

| Elle commence la lubrique danse … ses seins ondulent et, au frottement de ses colliers qui tourbillonnent, leurs bouts de dressent; sur la moiteur de sa peau les diamants, attachés, scintillent; ses bracelets, ses ceintures, ses bagues, crachent des étincelles; sur sa robe triomphale, couturée des perles, ramagée d'argent, lamée d'or, la cuirasse des orfčvreries dont chaque maille est une pierre, entre en combustion, croise des serpenteaux de feu, grouille sur la chair mate, sur la peau rose thé, ainsi que des insectes splendides aux élytres éblouissants, marbrés de carmin, ponctués de jaune aurore, diaprés de bleu d'acier, tigrés de vert paon. | She begins the lewd dance … her breasts quiver and, rubbed lightly by her swaying necklaces, their rosy points stand pouting; on her moist skin glitter clustered diamonds; from her bracelets, her belts, her rings, dart sparks of fire; over her robe of triumph, bestrewn with pearls, broidered with silver, studded with gold, a corselet of chased goldsmith's work, on each mesh a precious stone, seems ablaze with coiling fiery serpents, crawling and creeping over the pink flesh like gleaming insects with dazzling wings of brilliant colors, marbled with scarlet, patterned with yellow dawn, mottled with steely blue, striped with peacock green. |

Moreau: Salome Dancing Before Herod |

Moreau: The Apparition |

Heinrich Heine's 1841 epic poem Atta Troll took substantial liberty with the story but introduced the notion of a depraved but amorous fixation on the severed head, expressed in a tone of gentle derision. Heine envisioned Herodias as a lover of the Baptist who "perhaps a little peevish with her swain had him beheaded," became mad, "died of love's distraction" and rode through the air, whirling the bloody head above her "with childish laughter" and catching it "like a plaything." As for the logic of deeming Herodias to be the Baptist's lover, "Else there were no explanation / Of that lady's curious longing – / Would a woman want the head of / Any man she did not love?"

Salome also had inspired Hériodiade, an 1881 opera by Jules Massenet, its libretto a heavily romanticized adaptation of the Flaubert account. This time it is Salome who is enamored of John, who comforts her while she is in exile following the marriage of Herodias to Herod, who, in turn, is in love with Salome. Amid much political intrigue, Herod has the Prophet executed both at the urging of Herodias as payback for condemning her and to fulfill his illicit love of their daughter. At a lavish banquet Salome tries to kill her mother and then, in despair, stabs herself.

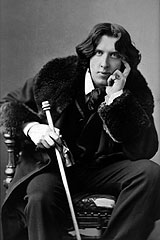

![]() And then

came Oscar Wilde (1854 - 1900), whose 1892 play was the most

extensive treatment of all, both a synthesis of its predecessors and a

strikingly original conception of sheer perversity and unabashed eroticism.

And then

came Oscar Wilde (1854 - 1900), whose 1892 play was the most

extensive treatment of all, both a synthesis of its predecessors and a

strikingly original conception of sheer perversity and unabashed eroticism.

Oscar Wilde |

- "There is no such thing as a moral or an immoral book."

- "Books are well written or badly written. That is all."

- "The morality of art is the perfect use of an imperfect medium."

- "Vice and virtue are to the artist materials for an art."

- "An ethical sympathy in an artist is an unpardonable mannerism of style."

Considered shocking and scandalous, performances were widely banned. Sarah Bernhardt's plans to mount the premiere in England collapsed when the Lord Chamberlain refused to license it on the ground that representations of Biblical characters were forbidden (a dubious pretext, since depictions of Samson, Moses and even Jesus somehow routinely managed to pass muster).

Beardsley Self-portrait |

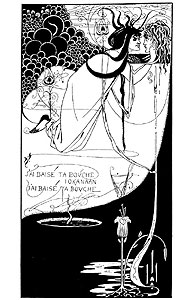

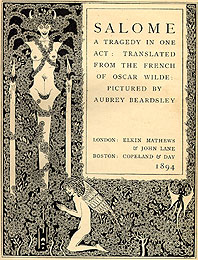

In the meantime, its English publication in 1894 added a new, highly influential element – drawings by 21-year old Aubrey Beardsley (who would die only four years later).

|

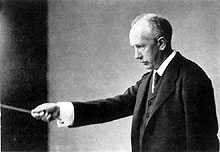

![]() Despite

bans elsewhere, Wilde's Salome found a welcome in Germany. It

was at a November 1902 Reinhart production in Berlin that Richard

Strauss (1864 - 1949) encountered it. Strauss was known

primarily as a conductor and the composer of tone poems in the tradition

of Liszt. In the decade from Aus Italien (From Italy) (1887) through

Don Juan, Tod und Verkärung (Death and Transfiguration),

Macbeth, Till Eulenspiegel, Also Sprach Zarathustra (Thus Spoke

Zarathustra) Don Quixote and Ein Heldenleben (A Hero's

Life) (1898) he "dealt with massively grandiose conceptions and a series

of very literal pictorial or characteristic episodes that stretched the

boundaries of purely musical form to the limit" (Tethys Carpenter). His

penultimate tone poem seemed to have exhausted his inspiration in the

genre – the bloated 45-minute Symphonia Domestica (Domestic

Symphony) (1903) was an idealized musical portrait of a day in his own

family life, ranging from sugary cooing of his baby to a fugal quarrel and a

rather literal depiction of love-making (with separate climaxes for himself

and his wife). Strauss wrote Salome from August 1903 through

September 1904 and completed the scoring in August 1905.

Despite

bans elsewhere, Wilde's Salome found a welcome in Germany. It

was at a November 1902 Reinhart production in Berlin that Richard

Strauss (1864 - 1949) encountered it. Strauss was known

primarily as a conductor and the composer of tone poems in the tradition

of Liszt. In the decade from Aus Italien (From Italy) (1887) through

Don Juan, Tod und Verkärung (Death and Transfiguration),

Macbeth, Till Eulenspiegel, Also Sprach Zarathustra (Thus Spoke

Zarathustra) Don Quixote and Ein Heldenleben (A Hero's

Life) (1898) he "dealt with massively grandiose conceptions and a series

of very literal pictorial or characteristic episodes that stretched the

boundaries of purely musical form to the limit" (Tethys Carpenter). His

penultimate tone poem seemed to have exhausted his inspiration in the

genre – the bloated 45-minute Symphonia Domestica (Domestic

Symphony) (1903) was an idealized musical portrait of a day in his own

family life, ranging from sugary cooing of his baby to a fugal quarrel and a

rather literal depiction of love-making (with separate climaxes for himself

and his wife). Strauss wrote Salome from August 1903 through

September 1904 and completed the scoring in August 1905.

Given his temperate propensities to that point, many observers have wondered at the depths from which Strauss suddenly summoned the acute caustic spur for Salome (and its equally jarring successor, Elektra [1908]).

Richard Strauss |

Howard Goodall offers another intriguing perspective – that Strauss's newly rebellious style was his artistic revenge on the society that had snubbed his first two operas. Guntram (1894) had been an abject failure, undoubtedly due to Strauss's unabashed imitation of his then-idol Wagner, both in the music and his own insipid libretto that finds a medieval singer in search of redemption. Feuersnot (In Need of Fire) (1901) barely fared better. It was a social satire based on a bawdy Flemish legend in which a humiliated suitor, ridiculed by the mayor's virgin daughter, exacts revenge through a spell that extinguishes all the town's fires that can only be lit from the heat of her first orgasm, which the suitor nobly agrees to educe and which Strauss depicts explicitly in a blazing orchestral passage. (Although the opera was condemned as obscene, it was a rather pale adaptation of the raunchy original legend, in which the girl had to strip, kneel on a table, and relight each fire from a flame that sprung from her backside as all the townsfolk passed by.) According to Goodall, Strauss's retaliation was Salome. Interestingly, after the esthetic explosion of Salome, both Wilde and Strauss (after Elektra) returned to the innocuous world of their earlier work – Wilde with witty social critiques (Lady Windermere's Fan, An Ideal Husband, The Importance of Being Earnest) and Strauss with operas of comic fantasy (Der Rosenkavalier, Ariadne auf Naxos, Intermezzo) to which he devoted himself exclusively until the chamber works of his final years.

The Viennese poet Anton Lindner offered to adapt the Wilde play into a libretto and sent some sample scenes, but Strauss opted instead for a fairly literal translation of the French original by Hedwig Lachmann. Although often hailed as the first opera to use an entire existing text, it was preceded by Debussy's 1892 Pelléas et Mélisande, set to nearly the full Maeterlink play. Moreover, Strauss did not set the whole play, but rather streamlined the text by removing about half; as analyzed by Roland Tenschert, he eliminated much of the theological contentions and the characters' motives and backgrounds, tweaked subordinate clauses that impaired the precision of the diction, reordered some words for more flowing melodic lines, and removed some metaphors, similes and repetitive language (while adding others for regularity and symmetry). Title page – first English edition |

Indeed, the text all but demanded a radical musical setting, which Strauss amply provided. In 1942, Strauss recalled his goals as providing the "authentic Eastern color and vibrant sunshine" that he felt most "Hebrew and oriental" operas lacked, He sought to achieve this through "truly exotic harmony that shimmered, especially in the strange cadences, like iridescent silk," including whole-tone scales, remote tonalities and bitonality, the last in order to depict the friction between sharply delineated and disparate personalities. The instrumentation is complex, creatively utilizing a huge orchestra with strings divided into as many as 11 parts to achieve extraordinary effects, including multiple harmonies. Indeed Paul Henry Lang considers Salome an orchestral opera in which the vocal parts struggle to project character against the onslaught of eloquent instrumentation and composer Gabriel Fauré called it "a symphonic poem with vocal parts added." Abert credits Strauss with associating characters with keys – e.g., John with A-flat, Salome with C-sharp. Others point to Wagnerian associative tonality, by which Strauss correlated a key with a dramatic element. As an example, Derrick Puffett notes that Strauss draws a connection between Salome (C-sharp major) and the moon (its enharmonic of D-flat major). The complexity increases with polytonality – Craig Ayrey notes that when Salome finally kisses Jokanann's mouth, we hear superimposed chords of c-sharp (representing her desire) and f-sharp (eroticism), yielding a bitter dissonance that underlines the plot's consequence of this fulfillment. Goodall cites it as "the most dissonant chord that had ever been heard" and contends that it is "hard to find a more aggressively uncomfortable combination of notes."

![]() Both play

and opera are cast in a single continuous act in real time (about 100

minutes) on a moonlit night on the terrace of Herod's palace. Salome,

bored, emerges from a banquet, is enthralled by the voice of Jokanaan's

mystical prophecies and entices Narraboth, the captain of the guard, to

disobey orders and bring the Prophet out of the cistern in which he is imprisoned.

Her fascination oscillates between revulsion and lust as he repulses her

advances and finally returns to the cistern. Drunken, wearied by

arguments with Herodias and a chorus of quarrelsome Jews,

Both play

and opera are cast in a single continuous act in real time (about 100

minutes) on a moonlit night on the terrace of Herod's palace. Salome,

bored, emerges from a banquet, is enthralled by the voice of Jokanaan's

mystical prophecies and entices Narraboth, the captain of the guard, to

disobey orders and bring the Prophet out of the cistern in which he is imprisoned.

Her fascination oscillates between revulsion and lust as he repulses her

advances and finally returns to the cistern. Drunken, wearied by

arguments with Herodias and a chorus of quarrelsome Jews,

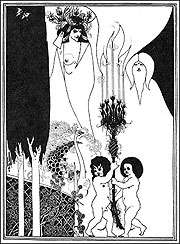

Beardsley: The Eyes of Herod |

First, Salome performs the "Dance of the Seven Veils," often heard in concert and on record as a free-standing orchestral piece. Del Mar calls it banal but brilliant, tossing together a potpourri of tunes from the opera, albeit in a way that Mann considers mechanical and thematically meaningless, with a result that Del Mar likens more to a Viennese waltz than to evoking the authentic Eastern color Strauss claimed to have sought. Consistent with Strauss having written it last, Heinz Becker considers the Dance a symphonic flashback in which Salome's emotional experiences are summed up, a catalog of past events and motives heard throughout the opera, all leading to "the most stunning contrast – a pause of total silence which makes manifest the speechlessness of the world." Ernest Krauss finds it dominated by the inner turmoil of Salome's corrupt psyche.

Staging the Dance encounters two fundamental challenges. First, Strauss aptly characterized Salome as the implausible combination of a 16-year old girl with the voice of an Isolde. At the risk of sounding callous let's just say that very few divas who can generate the huge vocal power of the title role have figures that are apt to convincingly lure Herod into his reckless bargain, much less dance without seeming grotesque.

Beardsley: The Belly Dance |

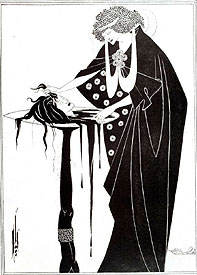

The dance concluded, to Herod's alarm and her mother's delight, Salome rebuffs Herod's attempts to dissuade her with fabulous gifts and insists upon the head of Jokanaan which, after great suspense fueled by grating harmonics played high on the double bass, the executioner delivers on a silver platter. Then begins a riveting apostrophe, unmatched in all of opera for its sheer queasy perversity, in which medium and message painfully collide; as John Williamson notes, Strauss's surfaces lend an esthetic glamour to the hysterical and depraved. Accompanied by spectacularly gorgeous music that in other contexts would buoy the most glorious surge of pristine natural love, Salome addresses the gory head, pouring out her obsession before the horrified court:

Ah! Thou wouldst not suffer me to kiss thy mouth, Jokanaan.Her soliloquy continues:

Well, I will kiss it now.

I will bite it with my teeth as one bites a ripe fruit. …

Beardsley: The Dancer's Reward |

Ah! Jokanaan, thou wert beautiful.She concludes: "the mystery of love is greater than the mystery of death." Seized with foreboding, Herod has the torches extinguished and flees in horror, as Herodias gloats and Salome persists, at first faintly and then rising to triumph:

Thy body was a column of ivory set upon feet of silver.

It was a garden full of doves and lilies of silver. …

In the whole world there was nothing so red as thy mouth.

Thy voice was a censer and when I looked at thee I heard a strange music.

Ah! I have kissed thy mouth, Jokanaan.At last, unable to bear any more, Herod orders his guards to kill her as the mood is shattered with crashing, violently dissonant chords (abruptly plunging from the distant fantasy of C-sharp major to the harsh earthy reality of C minor) – Goodell calls it a "musical earthquake" and suggests that it could represent Salome's first sexual consummation at the very moment of her death.

Ah! I have kissed thy mouth.

There was a bitter taste on thy lips.

Was it the taste of blood?

No! But perchance it is the taste of love.

They say that love hath a bitter taste.

But what of that? What of that?

I have kissed thy mouth, Jokanaan.

I have kissed thy mouth.

![]() Salome's oration crystallizes the work's essential tension between text and music, which prompted a groundswell of

condemnation from established critics who expectedly bridled against its

assault upon convention. Much of their censure arose from loathing

Wilde's lifestyle rather than his play or Strauss's opera. Thus Adam Röder

asserted in 1907, "If sadists, masochists, lesbians and homosexuals

come and presume to tell us that their crazy world of spirit and feeling is to

be interpreted as manifestations of art, then steps must be taken in the

interests of health. Art has no interest in sanctifying bestialities which arise

from sexual perversity."

Salome's oration crystallizes the work's essential tension between text and music, which prompted a groundswell of

condemnation from established critics who expectedly bridled against its

assault upon convention. Much of their censure arose from loathing

Wilde's lifestyle rather than his play or Strauss's opera. Thus Adam Röder

asserted in 1907, "If sadists, masochists, lesbians and homosexuals

come and presume to tell us that their crazy world of spirit and feeling is to

be interpreted as manifestations of art, then steps must be taken in the

interests of health. Art has no interest in sanctifying bestialities which arise

from sexual perversity."

The Dresden opening |

Censorship seemed an inevitable consequence. Indeed, although the Dresden premiere was a huge success, generating 38 curtain calls, the Vienna Censorship Board refused Mahler's attempt to mount the opera there due to the "objectionable nature of the whole story. … Sexual pathology is not suitable for our Court stage." The New York dress rehearsal (foolishly given on a Sunday morning right after church) was excoriated by a physician in a New York Times letter as "a detailed and explicit exposition of the most horrible, disgusting, revolting and unmentionable features of degeneracy that I have ever heard, read of or imagined." Not to be outdone, H. E. Krehbiel, the New York Tribune critic, cited the "moral stench" of the "pestiferous work" that was "abhorrent, bestial and loathsome." After a single performance dismayed patrons quashed the rest of the run. Salome would not be heard again in New York until 1934.

Elsewhere ridiculous accommodations were demanded. The Kaiser allowed presentation in Berlin only if a Star of Bethlehem appeared on the backdrop at the end.

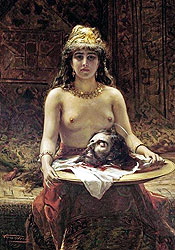

Leon Herbo: Salome (1889) |

Strauss was not one to deny the value of controversy: "The most certain road to universal fame is to have a work banned by the censor." Indeed, he had the last laugh, recalling in 1942: "On one occasion [Kaiser] Wilhelm II said, 'I'm sorry Strauss composed this Salome. He is going to do himself a lot of harm with this.' Thanks to this harm, I was able to afford my villa at Garmisch!"

![]() By

focusing on the play, early critics tended to dismiss the music as largely

needless. Wilde had described the prose of his play as having "refrains

whose recurring motifs make it like a piece of music and bind it together

like a ballad." Robert Hirshfeld wrote in the Weiner Abendpost that

the music had no esthetic reason, as the play had its own rhythms,

syncopation of thoughts, pauses and melding of harmonious and dissonant

words (and this in the German translation) – and so Strauss's contribution

"represents what is most annoying in art – superfluous and inorganic."

Writing in the same issue, Julius Korngold agreed: "If a poet makes his

own music, the last thing he needs is another one." Kalbeck felt that even

beyond the Dance the orchestra overwhelmed the stage action with

"colossal exaggeration" that "strips the text of subtlety." Indeed, Strauss's contribution

was belittled as not only pointless but superficial, literal and uninspired;

Stravinsky, on the cusp of his own Rite of Spring, called it

"triumphant banality." In that regard, comparisons with Wagner were

inevitable. Hirschfeld hailed Wagner's texts as designed to interweave

with his music, while Korngold asserted that "Wagner touches our feelings

with new greatness and beauty" while with Strauss he "felt nothing after the

curtain falls – the audience goes away empty." But such commentary

ignores that the two composers' approaches were intentionally disparate.

Consider the final arias of Salome and Wagner's Ring.

Wagner supports and invigorates the noble words and underlying theme of

Brunhilde's "Immolation Scene" with suitably glorious accompaniment

whereas Strauss's equally absorbing music deliberately contrasts with the

sheer perversity of Salome's fulfillment.

By

focusing on the play, early critics tended to dismiss the music as largely

needless. Wilde had described the prose of his play as having "refrains

whose recurring motifs make it like a piece of music and bind it together

like a ballad." Robert Hirshfeld wrote in the Weiner Abendpost that

the music had no esthetic reason, as the play had its own rhythms,

syncopation of thoughts, pauses and melding of harmonious and dissonant

words (and this in the German translation) – and so Strauss's contribution

"represents what is most annoying in art – superfluous and inorganic."

Writing in the same issue, Julius Korngold agreed: "If a poet makes his

own music, the last thing he needs is another one." Kalbeck felt that even

beyond the Dance the orchestra overwhelmed the stage action with

"colossal exaggeration" that "strips the text of subtlety." Indeed, Strauss's contribution

was belittled as not only pointless but superficial, literal and uninspired;

Stravinsky, on the cusp of his own Rite of Spring, called it

"triumphant banality." In that regard, comparisons with Wagner were

inevitable. Hirschfeld hailed Wagner's texts as designed to interweave

with his music, while Korngold asserted that "Wagner touches our feelings

with new greatness and beauty" while with Strauss he "felt nothing after the

curtain falls – the audience goes away empty." But such commentary

ignores that the two composers' approaches were intentionally disparate.

Consider the final arias of Salome and Wagner's Ring.

Wagner supports and invigorates the noble words and underlying theme of

Brunhilde's "Immolation Scene" with suitably glorious accompaniment

whereas Strauss's equally absorbing music deliberately contrasts with the

sheer perversity of Salome's fulfillment.

More recent commentary invariably focuses on the music and largely disregards the text. Henry Carse disparages Strauss's orchestration as highly skilled yet inclined to seek novelty by overloading the score, aiming at mere oddity and striving after elaborate effects. Another critic chided that he felt Strauss's orchestra was incomplete and suggested that for his next opera he should include "four locomotives with double boilers, three foghorns and a battery of howitzers." Yet William Mann cites the score as the most brilliant and far-reaching of all of Strauss's works for the very reason that repelled early critics – its deliberate disconnect between the aloof personages and its melodic richness and lyricism, as well as its musical characterization, thematic sculpture and coloring.

|

SOME SALOME THEMES Salome's motif The lilting, sultry Dance: The Prophet's two themes: The two variants of Salome's kiss: Salome's lust: |

Perhaps the opera is best viewed as a hugely impressive product of its time – as Frances Robinson notes, it is wedged between the final gasp of monarchy and the rise of Freudian analysis. Ernest Krause goes further, viewing the opera from a socialist perspective as a product of decadence "with its craving for sexual satiety and its blindness to reality [in which] the people are ignored and the characters entangle themselves in webs of perversely exaggerated passions which distort their view of the world and make normal relationships with other people impossible." Williamson contends that from a modern perspective much of the early sense of immorality has since devolved to kitsch. Puffett provides an apt summary of the diverse commentary by quipping that Salome is "a rich work – it has something to offer (and offend) everyone." But whether out of love or hate, few can resist it.

![]() While the opera Salome may seem sui

generis, imposing adaptations of the underlying tale continued to

emerge in music, film and dance.

While the opera Salome may seem sui

generis, imposing adaptations of the underlying tale continued to

emerge in music, film and dance.

Nazimova's Salome |

1923 saw a stunning feature film produced by and starring the exotic

Crimean/American Nazimova (née Miriam Levinton) with sets and

costumes that evoked Beardsley's drawings and subtitles firmly in the

spirit of Wilde ("Thy hair is like the black nights when the moon hides her

face").  Exquisitely paced and full of expressive closeups, it melds the

conventions of silent film with ballet. Teasing with extreme modesty (she

adds veils at the end of her dance and slinks behind a curtain to kiss

Jokanaan's mouth), Nazimova bristles with sexual longing, yet, following

Strauss's vision, acts with great subtlety, and much of her dancing is

comprised of immobile posing. Although incomparable when taken on its

own terms, the film was a flop at the time, fueled in part by aversion to the

lifestyle of Nazimova and the director, Charles Bryant, with whom she

shared a marriage of convenience – both were openly gay, as, rumor had

it, were much of the cast and crew.

Exquisitely paced and full of expressive closeups, it melds the

conventions of silent film with ballet. Teasing with extreme modesty (she

adds veils at the end of her dance and slinks behind a curtain to kiss

Jokanaan's mouth), Nazimova bristles with sexual longing, yet, following

Strauss's vision, acts with great subtlety, and much of her dancing is

comprised of immobile posing. Although incomparable when taken on its

own terms, the film was a flop at the time, fueled in part by aversion to the

lifestyle of Nazimova and the director, Charles Bryant, with whom she

shared a marriage of convenience – both were openly gay, as, rumor had

it, were much of the cast and crew.

Two subsequent cinema incarnations were inventive integrations of a

performance into a backstory. Ken Russell's 1988 Salome's Last

Dance imagines a flamboyant Wilde visiting a brothel where the play is

being staged by prostitutes, while Carlos Saura's 2002 Salome

absorbs a flamenco version into biographies of the principal dancers as

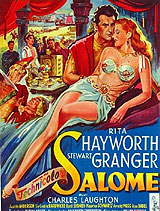

they rehearse.  In contrast, Hollywood's take was laughably trite – Rita

Hayworth starring in William Dieterle's 1953 Salome, a predictable

love story complete with stereotyped "oriental" dance music, overwrought

acting by a slobbering Charles Laughton as Herod and a gloating Judith

Anderson as Herodias, and a happy ending as Salome flees her parents

with a handsome palace guard to bask in redemption at the Sermon on the

Mount.

In contrast, Hollywood's take was laughably trite – Rita

Hayworth starring in William Dieterle's 1953 Salome, a predictable

love story complete with stereotyped "oriental" dance music, overwrought

acting by a slobbering Charles Laughton as Herod and a gloating Judith

Anderson as Herodias, and a happy ending as Salome flees her parents

with a handsome palace guard to bask in redemption at the Sermon on the

Mount.

We might also note in passing that the subject was sufficiently intriguing to spawn pop musical works with little connection beyond the title.

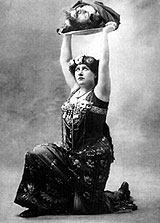

Maude Allen as Salome |

And speaking of risqué theatrical offshoots, perhaps the most notorious (and successful – 250 London performances in 1908) was Maud Allen's "Vision of Salome," a music-hall act combining posing and, as one critic put it, "sensuous gyrations." A Dublin detractor derided (in great detail) her self-designed diaphanous and highly-revealing costume (which, he admitted, "a goodly section of the audience applauded very vigorously") and the New York Sun reported that her "dance [was] of only one veil and not much of a veil at that. She does not take it off. She does not need to." (Allen's life was even more sensational than her staging – her brother was hanged for a double murder, and, shades of Wilde, she brought and lost a highly-publicized defamation lawsuit against accusations of sexual perversion made by a member of Parliament who was known for far-fetched raving that Jews, gays and German spies were undermining the moral fabric of British society.)

![]() Recordings of Salome face an immediate quandary.

Should an effort be made to intensify the impact of the original in order to

jolt modern listeners who are largely immune from the levels that a

century ago sufficed to overwhelm audiences still immersed in Victorian

propriety (a burden further magnified by having to forego the visual

aspect)? Or should the production be relatively reticent, leaving the

revulsion to be inferred? Strauss presumably would have opted for the

latter, having told the orchestra at the premiere that he wanted a light-toned

lyrical approach that should be played as Mendelssohnian "fairy music,"

like a "scherzo with a fatal conclusion," and having sought a lyric soprano

for the title role, which he envisioned as a chaste but sexy virgin, so as to

add complexity to the character. Indeed, the conductor of the premiere,

Ernest von Schuch, selected and coached by Strauss, was reputed for his

refinement. Yet Strauss was hardly consistent in his counsel, as he

reportedly instructed the orchestra during a rehearsal: "We want

wild beasts here" and admonished them to play louder since he could still

hear the singers. Even so, he chastised Toscanini, who led the Italian

premiere, for having "slaughtered the singers and the drama" beneath a

"piteously raging orchestra" to "perform a symphony without singers" and contrasted it with Germany,

where "the orchestra accompanies and one understands the singers'

every word" – a

curious complaint, in light of the primacy of vocals in Italian opera, of which

Toscanini was a foremost advocate. And while later known for his objective podium style, Strauss was

described toward the launch of his career as doing "a fantastic dance while

conducting," and was scolded by his father, the principal horn of the

Munich court orchestra, for making "snake-like gestures."

Recordings of Salome face an immediate quandary.

Should an effort be made to intensify the impact of the original in order to

jolt modern listeners who are largely immune from the levels that a

century ago sufficed to overwhelm audiences still immersed in Victorian

propriety (a burden further magnified by having to forego the visual

aspect)? Or should the production be relatively reticent, leaving the

revulsion to be inferred? Strauss presumably would have opted for the

latter, having told the orchestra at the premiere that he wanted a light-toned

lyrical approach that should be played as Mendelssohnian "fairy music,"

like a "scherzo with a fatal conclusion," and having sought a lyric soprano

for the title role, which he envisioned as a chaste but sexy virgin, so as to

add complexity to the character. Indeed, the conductor of the premiere,

Ernest von Schuch, selected and coached by Strauss, was reputed for his

refinement. Yet Strauss was hardly consistent in his counsel, as he

reportedly instructed the orchestra during a rehearsal: "We want

wild beasts here" and admonished them to play louder since he could still

hear the singers. Even so, he chastised Toscanini, who led the Italian

premiere, for having "slaughtered the singers and the drama" beneath a

"piteously raging orchestra" to "perform a symphony without singers" and contrasted it with Germany,

where "the orchestra accompanies and one understands the singers'

every word" – a

curious complaint, in light of the primacy of vocals in Italian opera, of which

Toscanini was a foremost advocate. And while later known for his objective podium style, Strauss was

described toward the launch of his career as doing "a fantastic dance while

conducting," and was scolded by his father, the principal horn of the

Munich court orchestra, for making "snake-like gestures."

John Culshaw, producer of the 1961 Solti recording, raises a telling point – not all of Strauss's extreme blends of tone color are practicable in the theatre with a fixed layout of the instruments, but rather are better revealed by variable deployment of the orchestral forces. Thus Culshaw contends that to capture all the audible nuances in their correct proportion requires technical intervention through creative microphone placement and mixing, with the result of placing the listener closer to the score and thus the drama.

Emmy Destinn as Salome |

Such technological luxuries were unavailable to the pioneers – for better (spontaneity) or worse (inhibition, flaws) what they sang went directly onto the disc. In a 1911 New York Times interview, Johanna Gadski claimed that she would never sing Salome and that Strauss had told her: "I don't write my music for people with beautiful voices like yours." Yet in 1908 she had recorded a brief, 93 second snippet of "Ich bin verleibt in deinem Leib" ("I am amorous of thy body"), in which Salome lusts for the (then-living) Jokanaan, in a high, tremulous, cutting voice without much semblance of craving or temptation. The year before, Emmy Destinn cut two more compelling sides from the same scene. Her own "Ich bin verleibt" is noble, as befits a princess, yet ardent, as suits an adolescent's first overwhelming crush. Her ensuing "Dein Haar is grässlich!" ("Thy hair is horrible!") drips with rushed venom and fully reflects her wrath at being snubbed until the final line ("Lass mich ihn küssen, deinin Mund") ("Let me kiss thy mouth") melts into a tender plea. Despite some intonation issues, her vibrato as well as her overall bearing is exquisitely expressive.

Curiously, the first recording of the final scene, seemingly the most inviting excerpt for a dramatic soprano, had to await 1921, when an eight-minute abridgement was cut by German soprano Barbara Kemp. Her rendition, conducted by Leo Blech (rather than her husband-to-be, c Von Schillings), is rather lightweight and makes little attempt to convey the princess's perverse and chaotic emotions.

Gota Ljungberg as Salome |

The very end of the acoustical era brought the first substantial set of Salome excerpts from HMV in 1924 – six very full 12" sides (26˝ minutes total) of the opening scene (heavily abridged), the first stanza of Jokanaan's harangue ("Wo ist er") couched within churning orchestral passages, Salome's Dance (two sides) and her concluding apostrophe (abbreviated to two sides), the last of which is endowed by Göta Ljungberg with a bracing fusion of purity, command and sheer vocal splendor. The amount of orchestral detail captured by the archaic apparatus is truly remarkable and, atypically for acoustic vocal recordings, the balances do not favor the singers. Albert Coates whips the score into a riveting frenzy, as might be expected from a conductor known for his extraordinary vitality on disc.

The most promising set of extended excerpts – potentially, at least – was led by the composer himself on a set of 78 rpm sides privately recorded by Hermann May and issued only in 1994 as part of Koch Schwann's Vienna State Opera Live CD edition.

Richard Strauss conducting |

Recordings of the final scene continued. Two seem especially significant.

Marjorie Lawrence as Salome |

Perhaps the most acclaimed of all free-standing final scenes is the 1949 recording by Ljuba Welitsch, cut shortly after her spectacular Met debut. Francis Robinson, the long-time assistant director of the Met, claimed that her debut spawned the longest and loudest ovation he had ever heard.

Ljuba Welitsch as Salome |

The 1949 version has

brighter sound and catches Welitsch in fresher voice, but both provide

exceptional object lessons in vocal acting. Experts have acclaimed

both as the greatest Salomes on record.

The 1949 version has

brighter sound and catches Welitsch in fresher voice, but both provide

exceptional object lessons in vocal acting. Experts have acclaimed

both as the greatest Salomes on record.

Another highly renowned closing scene was again led by Reiner in late 1955, this time for RCA with the Chicago Symphony Orchestra and Inge Borkh, who sings in a rich, quavering voice. Known as much for her acting as her singing, her more shaded tone and expression is matched by the warmer ambiance Reiner provides, abetted by the early stereo recording, which spreads the accompaniment over a convincing soundstage to achieve a sense of atmosphere and display subtleties of orchestration beyond the reach of a single channel to convey. Borkh, too, left us a celebrated complete Met performance. While Dmitri Mitropoulos leads tempestuous orchestral interludes, the sustained intensity (partly a function of heavy dynamic compression) brooks no chance for respite or a hint of tenderness, even as Salome first marvels over the Prophet's body and tenderly (if perversely) basks in contemplation of her kiss in the finale. Indeed, Borkh's unflagging huge voice seems downright Wagnerian and too lush – more a worldly Brünhilde than a raw adolescent, albeit a driven one.

![]() In considering complete recordings of Salome, I

tend to focus on the conductor, Salome and Herod if only by default, as

the other major roles seem mostly one-dimensional and thus present little

opportunity for interpretive personality – the Captain of the Guard

Narraboth is hopelessly stricken with Salome but bound by duty, the Page

constantly warns him of the disastrous consequences of his forbidden

desire, Herodias is relentlessly driven by disgust for her husband and maniacal hatred

of Jokanaan, who, in turn, prophesizes with inflexible ideology (except for a

brief ecstatic vision in which he implores Salome to seek Christ). All are

rendered quite well, if predictably, in all the recordings I've heard. At the

other extreme, interpreters of Salome are faced with the daunting, if not

inherently impossible, task of depicting a character who evolves in the

course of an hour's real time from bewildered to lustful, manipulative, cruel and

finally deranged. The comprehensive Operadis website lists

79 complete Salome recordings as of 2009 of which I've focused on

studio renditions. The following headnotes list: the

conductor; the singers of Salome, Herod, Jokanaan, Herodias; the

orchestra (the original label, the year of first issue).

In considering complete recordings of Salome, I

tend to focus on the conductor, Salome and Herod if only by default, as

the other major roles seem mostly one-dimensional and thus present little

opportunity for interpretive personality – the Captain of the Guard

Narraboth is hopelessly stricken with Salome but bound by duty, the Page

constantly warns him of the disastrous consequences of his forbidden

desire, Herodias is relentlessly driven by disgust for her husband and maniacal hatred

of Jokanaan, who, in turn, prophesizes with inflexible ideology (except for a

brief ecstatic vision in which he implores Salome to seek Christ). All are

rendered quite well, if predictably, in all the recordings I've heard. At the

other extreme, interpreters of Salome are faced with the daunting, if not

inherently impossible, task of depicting a character who evolves in the

course of an hour's real time from bewildered to lustful, manipulative, cruel and

finally deranged. The comprehensive Operadis website lists

79 complete Salome recordings as of 2009 of which I've focused on

studio renditions. The following headnotes list: the

conductor; the singers of Salome, Herod, Jokanaan, Herodias; the

orchestra (the original label, the year of first issue).

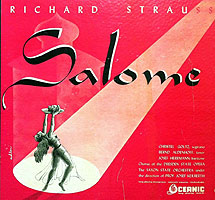

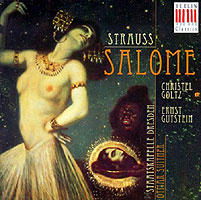

- Joseph Keilberth; Christel Goltz, Josef Herrmann, Bernd Aldenhoff, Inger Karén; Dresden Staatskapelle (Oceanic LP, 1948)

This was the first complete Salome to have been released.

Needless to say, that in itself is significant, as the full force of the finale

can truly be felt only as the culmination of the rest, rather than as a free-standing set piece. Goltz was famed for this role and was known for her

range, volume and intensity. Although spared the need for such stamina

here, she routinely did the Dance herself, although it undoubtedly helped

that she had been born into a family of acrobats and trained as a dancer

before turning to singing.

Her apostrophe is especially chilling, as she

intones her depraved lines in a pure, sweet girlish timbre, adding an

uncommon layer of perversion to a complex portrait of a brat way out of

her depth. Like most of the singers and conductors in Salome

recordings, Keilberth was known as a Wagner interpreter. Yet as an

extension of the stylistic example of Strauss's own recording, and fully

consistent with Goltz's approach, the entire production displays crystalline

diction sufficient to imply characterization without sacrificing the emotional

content, compromising the musical flow or breaking a musical line, thus

treading a subtle edge between the classicism of Mozartean influence and

the modern toxicity of the plot. The sound has remarkable clarity for its

age and source. Actually a recorded radio broadcast, it benefits from the

continuity of a live performance without expending the considerable

energy required for staging and the inevitable resulting problems of balance. It also

boasts the pedigree of having emanated from Dresden, where the

premiere had been given.

Her apostrophe is especially chilling, as she

intones her depraved lines in a pure, sweet girlish timbre, adding an

uncommon layer of perversion to a complex portrait of a brat way out of

her depth. Like most of the singers and conductors in Salome

recordings, Keilberth was known as a Wagner interpreter. Yet as an

extension of the stylistic example of Strauss's own recording, and fully

consistent with Goltz's approach, the entire production displays crystalline

diction sufficient to imply characterization without sacrificing the emotional

content, compromising the musical flow or breaking a musical line, thus

treading a subtle edge between the classicism of Mozartean influence and

the modern toxicity of the plot. The sound has remarkable clarity for its

age and source. Actually a recorded radio broadcast, it benefits from the

continuity of a live performance without expending the considerable

energy required for staging and the inevitable resulting problems of balance. It also

boasts the pedigree of having emanated from Dresden, where the

premiere had been given.

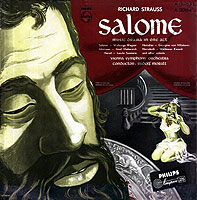

- Rudolf Moralt; Walburga Wegner, Josef Metternich, László Szemere, Georgine von Milinkovic; Vienna Symphony (Philips, 1952)

Perhaps because both conductor and cast had primarily local (albeit worthy) reputations, this recording is often overlooked. Yet it is significant as the very first studio recording of Salome. It also boasts a special pedigree of its own – Moralt was Strauss's nephew, although biographies do not suggest a strong professional bond. His brief discography focuses on Wagner (including a complete recorded Ring) and Mozart (three complete operas) – a suitable blend for Salome, as his fleet timing creates a propulsive sense of inevitability while conveying the density of the music, despite an overly bright recording. As chief conductor at the Vienna State Opera from 1940 to 1958, Moralt focused his energies on restoring the excellence of that famed ensemble, and so it seems appropriate that he didn't feel compelled to populate his cast with outside stars. The voices are credible if not especially distinguished, but that serves to keep the production on a human scale. Volume is used creatively to reflect the balance of personalities – thus, Salome's repeated demands for the prophet's head are constantly buried beneath Herod's desperate attempts to dissuade her, and her final line is not the usual lung-busting, ringing triumph but withers in exhausted ambivalence. A rudimentary sound effect (the earliest I've encountered among Salome recordings) adds echo when Salome first peers down into the cistern and to Jokanaan's lines from within it. Incidentally, as if to emphasize the need to apply one's own critical perspective and to take professional views with a proverbial grain of salt, two Musical America reviews of Wegner's 1952 Met appearances (in Strauss's Elektra) generated vastly different reactions – Robert Sabine hailed her blazing intensity, while Cecil Smith asserted "Nature's firm intention that she restrict herself to music that is gentler."

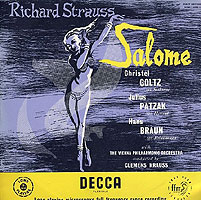

- Clemens Krauss; Christel Goltz, Hans Braun, Julius Patzak, Margareta Kenney; Vienna Philharmonic (Decca/London, 1954)

Of all the Salome conductors on record, Krauss had the

closest relationship to Strauss, as he prepared the premieres of three late

operas under the composer's direction, wrote the libretto for

Capriccio and recorded the first full set of the tone poems (after

Strauss's own series). Thus it seems appropriate that this Salome, his

penultimate recording, combines the conventional style of the late Strauss

operas with the lush romanticism of the Strauss tone poems, abetted by

the famed opulent sound of the Vienna Philharmonic.

The Dance, shorn

of its ingrained edge, is especially smooth and silky, and perhaps all the

more creepy by hiding its undertone of depravity beneath an aura of

alluring charm. Elsewhere, though, the sting needed to fully convey the

expressionist impact is veiled beneath glossy execution and the final

chords are bereft of their needed shock. Goltz, sounding considerably

more mature than in 1948, is both more expressive (as when she whispers

her anxiety waiting for the executioner to perform) and grand, culminating

in a sumptuous apostrophe brimming with beauty and splendor that is all

the more unsettling in contrast to the chilling tale. Julius Patzak renders

Herod with a wide range of expression, from barely stylized speech to full

song.

The Dance, shorn

of its ingrained edge, is especially smooth and silky, and perhaps all the

more creepy by hiding its undertone of depravity beneath an aura of

alluring charm. Elsewhere, though, the sting needed to fully convey the

expressionist impact is veiled beneath glossy execution and the final

chords are bereft of their needed shock. Goltz, sounding considerably

more mature than in 1948, is both more expressive (as when she whispers

her anxiety waiting for the executioner to perform) and grand, culminating

in a sumptuous apostrophe brimming with beauty and splendor that is all

the more unsettling in contrast to the chilling tale. Julius Patzak renders

Herod with a wide range of expression, from barely stylized speech to full

song.

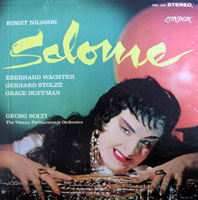

- Georg Solti; Birgit Nilsson, Gerhard Stolze, Eberhard Wachter, Grace Hoffman; Vienna Philharmonic (Decca/London, 1961)

This first stereo Salome was produced by the same team of soprano, orchestra, conductor and technical crew that was in the midst of crafting the first stereo Ring. In accompanying notes, the engineers boasted that their innovation of "resonance control" (i.e., precise control of acoustics) was "the greatest single development in recorded opera since the inception of stereophonic sound." While that may seem dubious nowadays, they were writing when stereo itself was barely a decade old. Even so, their achievement remains stunning, with an astounding balance of vibrant atmosphere, incisive detail and sheer sonic power. (I can't vouch for various CD transfers – I'm sticking with my near-mint original vinyl set that sounds sensational.) The orchestral impression is rich with gripping bass yet blazing with sharp, vivid highlights, precisely balanced against the voices so as to overwhelm them at dramatically appropriate times. Astride it all is Nilsson, whose awesome purity, breath control and sheer power affords her the luxury of exquisite coloring and subtlety without a hint of strain or compromising her mesmerizing presence that dominates every moment she is heard and reverberates in the interstices. Her interview with Jokanaan begins as beguiled and evolves into a hair-raising confrontation. When she pleads with Herod for the prophet's head she lets him dominate, never raising her voice above patient, insistent conversation throughout his hysterics, yet we know from her first confident, hypnotic note who will prevail. Her apostrophe, resplendent with tonal beauty and effortless vocal production, paints a portrait of self-assured triumph, a Brünhilde oblivious to all else and set on an inexorable course toward her own destiny. Her final lines are barely audible until the very end, drawing us deeply one final time into her sick, eerie, private world. Even a half-century later, it's hard to imagine a more thrilling, visceral Salome (or a scarier cover!).

- Otmar Suitner; Christel Goltz, Helmut Melchert, Ernst Gutstein, Siw Ericsdotter; Dresden Staatskapelle (Eterna LP, 1963)

Like the Moralt, this set, too, is often overlooked, perhaps because East German

imports weren't keenly sought in the West at the height of the Cold War. A Krauss student, Suitner has a fine feel for the score – objective but never dull,

letting the inherent drama develop with minimal personal input and a

superb balance that conveys all the instrumental splendor without ever

calling attention to itself. Not only the Dance, but other orchestral

passages (notably Jokanaan emerging from and returning to the cistern)

are atmospheric, propulsive and hugely effective, spiced by rousing

timpani. (An unusual benevolent touch – the Jews' quarrel sounds more

like a heated discussion than a mean-spirited fight, and he eliminates

altogether their silly cries of "Oh, oh, oh" when Herod, in desperation but to

no avail, offers Salome the veil of the tabernacle if she will spare

Jokanaan.) Yet while the supporting cast of relative unknowns is decent

enough, the result remains deeply flawed. Salome, after all, is

Salome.

In her third studio recording (no other soprano boasts even two),

Goltz has lost the character, appeal and control of her former outings

and instead shakes all her held notes with fearsome tremolo and sounds

like an aging diva. Her sheer power remains and dominates throughout,

but judging from her voice alone (as we must), she could never be

mistaken for a youthful innocent prone to corruption, nor bend the captain

of the guard, let alone Herod, to her will, but rather merely shouts them all

down, even in the crucial scene when she repeatedly demands the

Prophet's head, neither steadfastly nor with rising intensity, and during the final oration she sounds merely exhausted rather than

exulting in triumph.

Despite an inflated stereo spread, the sonic fidelity is convincing, although

for some reason Herod is miked with an annoying metallic overtone and

other voices are heard with curiously different degrees of presence.

In her third studio recording (no other soprano boasts even two),

Goltz has lost the character, appeal and control of her former outings

and instead shakes all her held notes with fearsome tremolo and sounds

like an aging diva. Her sheer power remains and dominates throughout,

but judging from her voice alone (as we must), she could never be

mistaken for a youthful innocent prone to corruption, nor bend the captain

of the guard, let alone Herod, to her will, but rather merely shouts them all

down, even in the crucial scene when she repeatedly demands the

Prophet's head, neither steadfastly nor with rising intensity, and during the final oration she sounds merely exhausted rather than

exulting in triumph.

Despite an inflated stereo spread, the sonic fidelity is convincing, although

for some reason Herod is miked with an annoying metallic overtone and

other voices are heard with curiously different degrees of presence.

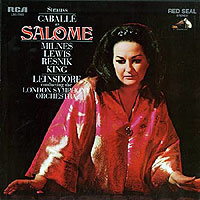

- Erich Leinsdorf; Montserrat Caballé, Richard Lewis, Sherrill Milnes, Regina Resnik; London Symphony (RCA, 1968)

The Solti production was a formidable act to follow, but if it seems too garish or extreme then this rendition should amply satisfy. Leinsdorf's career began in opera, where he trained under both Toscanini and Walter, and thus brings a compelling blend of his mentors' meticulous precision and atmospheric empathy that tends to flow smoothly rather than in edgy fits. Appropriately, RCA's sonics are far more natural than Decca's (here, too, I'm judging from vinyl) yet with creative details. Thus, to add echo for the cistern Milnes sang into a large metallic exhaust hood over a stove in the venue kitchen. Much of Herod's lines, even when agitated, are nestled within the instrumentation, as if to depict him as a petty man, impotent to control his surroundings, much less his wife or daughter. Caballé, renowned for bel canto, renders a warm and deeply moving apostrophe in which we can sense human emotions within the horrifying context, as if an ardent lover was pouring out her innermost cravings to an absent object of irresistible desire. Overall, this remains a fine, idiomatic realization that grows with familiarity. In 1977 Caballé cut the finale for DG with Bernstein and the Orchestre National de France; as would be expected it's vastly different, propelled by the conductor's trademark muscular force and bursting with overt vehemence.

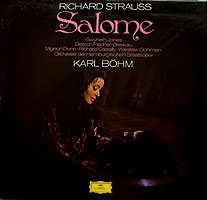

- Karl Bohm; Gwyneth Jones, Richard Cassily, Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, Mignon Dunn; Hamburg State Opera (DG, 1970)

Technically not a studio recording, this was cobbled from live performances

and rehearsals, but unlike others it was planned for commercial release

and made by a major label on professional equipment with a hushed

audience and minimal stage noise. Bohm was an associate of Strauss,

the dedicatee of his 1938 opera Daphne, and known for reliable,

stable renditions with due attention to detail, and an extra dollop of energy

outside the studio. Here, at age 76, he's commendably brisk, although the

voices' higher level and sharper presence elevates their sense of drama at

the expense of the orchestra, whose contributions sound muted by

comparison, with the Dance especially deflated.

Jones is a Wagnerian

soprano, but with a lighter voice and wider emotional range to fulfill the

perceptive psychological vision of the producer August Everding, who considers Salome to be "a

white dove with a young, innocent girl's tendency toward depravity [who]

has learned to so despise her mother's unchastity that she confronts men

with chaste superiority until one man confronts her with chaste superiority

of his own," "a closed white flower … exposed to the rays of a dazzling

sun – Jokanaan, whose rejection of her advances awakens her so that the

flower opens and perishes." Jones's finale, in particular, is uncommonly sweet and

thus all the more perverse. Fischer-Dieskau is largely wasted in the role of

the Prophet, which demands little of his trademarked sensitivity and

heartfelt expression. The booklet with the LP set provides a fascinating

comparison between the libretto and the full original French text of Wilde's play (and an

English translation), conveniently marked to indicate the portions Strauss

cut or altered.

Jones is a Wagnerian

soprano, but with a lighter voice and wider emotional range to fulfill the

perceptive psychological vision of the producer August Everding, who considers Salome to be "a

white dove with a young, innocent girl's tendency toward depravity [who]

has learned to so despise her mother's unchastity that she confronts men

with chaste superiority until one man confronts her with chaste superiority

of his own," "a closed white flower … exposed to the rays of a dazzling

sun – Jokanaan, whose rejection of her advances awakens her so that the

flower opens and perishes." Jones's finale, in particular, is uncommonly sweet and

thus all the more perverse. Fischer-Dieskau is largely wasted in the role of

the Prophet, which demands little of his trademarked sensitivity and

heartfelt expression. The booklet with the LP set provides a fascinating

comparison between the libretto and the full original French text of Wilde's play (and an

English translation), conveniently marked to indicate the portions Strauss

cut or altered.

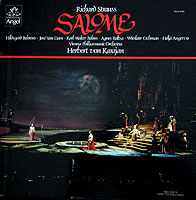

- Herbert von Karajan; Hildegard Behrens, Karl-Walter Böhm, José Van Dam, Agnes Baltsa; Vienna Philharmonic (Angel, 1977)

In keeping with his reputation for control and highly-polished precision, Karajan leads with a rather attenuated, leisurely-paced feeling of mystery that suggests ancient legend – until the final scene, which blooms into full- blown romanticism. Others praise the reading as sensual or even ironic, but I wouldn't go quite that far; rather, although certainly avoiding both the calculated objectivity of much of Karajan's work as well as the electric excitement of others', sonorities are richly blended, with sufficient detail but without calling undue attention to the components, and the orchestral contribution largely is content to serve as accompaniment, as it would be in the opera house pit, leaving the singers to characterize their roles. (Although produced and released by EMI, the technical crew was Decca's, and the result, with substantial emphasis on the mid-range, differed from their customary emphatic sound.) Behrens, a Karajan discovery making her debut on records, was already 40 at the time and sounds warm and expressive, but manages to kindle considerable charm as she lures Narraboth into letting Jokanaan out of the cistern, and then just as easily turns it off when her mood darkens.

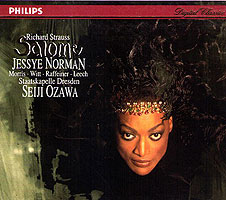

- Seiji Ozawa; Jessye Norman, James Morris, Walter Raffeiner, Kerstin Witt; Dresden Staatskapelle (Philips, 1990)

- Zubin Mehta; Éva Marton, Bernd Weikl, Heinz Zednik, Brigitte Fassbaender; Berlin Philharmonic (Sony, 1990)

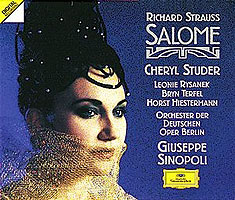

- Giuseppe Sinopoli; Cheryl Studer, Bryn Terfel, Horst Hiestermann, Leonie Rysanek; Deutsche Oper Berlin (DG, 1990)

After a considerable drought, 1990 brought a bounty of no fewer than

three studio Salomes. Expert opinions on these tend to be more

amusing than revealing, as each variously praises a different one at the

expense of the others, but perhaps the lack of a consensus is warranted

by their distinctive natures and appeal.

Norman's light vibrato hints at

youthfulness toward the top of her wide range (and spares us the full diva

treatment at the end), but her creamy, near-mezzo tone predominates and

denies much sense of evolution (and, in an unusual role reversal, sounds

deeper than her mother). She's especially convincing when singing of

dark things (peering into the cistern; pondering the Prophet's hair). Yet the

sheer luster of her tone and phrasing is intoxicating, although it tends to

negate characterization and often overpowers the accompaniment, once

again by the Dresden forces, this time led by Ozawa, who often seems

more dutiful than engaged. Mehta, while more responsive, unleashes

the accustomed excellence of the Berlin Philharmonic during the

orchestral passages of Jokanaan's return to the cistern and a fine, moody

Dance seething with delicacy and grace, but otherwise largely hides

beneath the voices. Marton, though, from the outset is far more matronly

than vulnerable or impressionable and tends to blunt any sense of

atmosphere or psychic progression. In my personal favorite of the 1990 crop of

Salomes, Sinopoli, known for his deeply intellectual approach to

music and his sensitivity to textures, crafts radiant support for the

variegated expressive breadth of Studer, who shapes every word with

dramatic purpose and conversational ease, especially in softer passages

in which she demands our attention more than in overly insistent segments

and constantly contrasts her placid textures to Herod's hysterics and

Jokanaan's stentorian moralizing. As in the Bohm LP box, the CD booklet

compares Wilde's full original text with Strauss's

abridged libretto. The sonic allure of all three of these sets is terrific.

Norman's light vibrato hints at

youthfulness toward the top of her wide range (and spares us the full diva

treatment at the end), but her creamy, near-mezzo tone predominates and

denies much sense of evolution (and, in an unusual role reversal, sounds

deeper than her mother). She's especially convincing when singing of

dark things (peering into the cistern; pondering the Prophet's hair). Yet the

sheer luster of her tone and phrasing is intoxicating, although it tends to

negate characterization and often overpowers the accompaniment, once

again by the Dresden forces, this time led by Ozawa, who often seems

more dutiful than engaged. Mehta, while more responsive, unleashes

the accustomed excellence of the Berlin Philharmonic during the

orchestral passages of Jokanaan's return to the cistern and a fine, moody

Dance seething with delicacy and grace, but otherwise largely hides

beneath the voices. Marton, though, from the outset is far more matronly

than vulnerable or impressionable and tends to blunt any sense of

atmosphere or psychic progression. In my personal favorite of the 1990 crop of

Salomes, Sinopoli, known for his deeply intellectual approach to

music and his sensitivity to textures, crafts radiant support for the

variegated expressive breadth of Studer, who shapes every word with

dramatic purpose and conversational ease, especially in softer passages

in which she demands our attention more than in overly insistent segments

and constantly contrasts her placid textures to Herod's hysterics and

Jokanaan's stentorian moralizing. As in the Bohm LP box, the CD booklet

compares Wilde's full original text with Strauss's

abridged libretto. The sonic allure of all three of these sets is terrific.

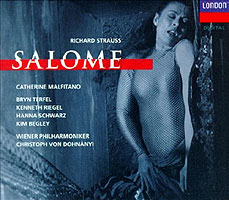

- Christoph von Dohnányi; Catherine Malfitano, Bryn Terfel, Kenneth Riegel, Hanna Schwarz; Vienna Philharmonic (Decca, 1994)

Dohnányi leads the Vienna Philharmonic in yet another studio

Salome in a surprisingly relaxed and steady (one might say

featureless) reading, complete with a rather perfunctory Dance, far from

the expected dynamism one might expect from a student of Bernstein and

Solti. Even so, uncommon details emerge here and there – ironic dreamy

arpeggios as Herod rhapsodizes over Salome's request for a silver platter

before he learns what she wants on it, and a dynamic voicing of the spooky

"Salome chord" before her final lines.

Yet, I can't help but feel that a more

vivid approach is needed, especially nowadays, in order to impart even a

small measure of the essential shock that Salome generated in its

time (and that the composer clearly intended). By slighting the orchestral

contribution, Dohnányi relegates the dominant role to the vocals, as seems

proper in any opera. Fortunately, Maltifano impresses as a fine singing

actress, with a warbling voice that, unlike Goltz in 1963, she uses

expressively for tightly-wound nervous energy (and with a lighter texture)

for an apt portrayal of a girl who ventures way beyond the scope of her shallow adolescent emotional depth.

Despite her ability to unleash full power, she often exercises considerable

restraint and manages to exude plausible allure.

Yet, I can't help but feel that a more

vivid approach is needed, especially nowadays, in order to impart even a

small measure of the essential shock that Salome generated in its

time (and that the composer clearly intended). By slighting the orchestral

contribution, Dohnányi relegates the dominant role to the vocals, as seems

proper in any opera. Fortunately, Maltifano impresses as a fine singing

actress, with a warbling voice that, unlike Goltz in 1963, she uses

expressively for tightly-wound nervous energy (and with a lighter texture)

for an apt portrayal of a girl who ventures way beyond the scope of her shallow adolescent emotional depth.

Despite her ability to unleash full power, she often exercises considerable

restraint and manages to exude plausible allure.

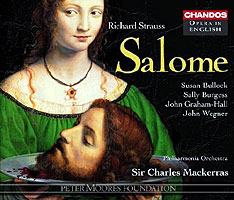

- Charles Mackerras; Susan Bullock, John Graham-Hall, John Wegner, Sally Burgess, Andrew Rees; Philharmonia Orchestra (Chandos CD, 2008)

Issued 14 years after the prior studio Salome, the Mackerras set serves to raise two related questions. First, in light of the economic pressures that increasingly threaten the traditional model for recording major works, will there be any more studio Salomes? And, second, given the added inspiration captured in most concert presentations and the enhanced experience afforded by video, does it even matter? But those are questions for another day.

![]() The facts, references and quotations in this article are taken from the following

sources. Unless otherwise noted, I'll take the credit – and blame – for the

musical judgments.

The facts, references and quotations in this article are taken from the following

sources. Unless otherwise noted, I'll take the credit – and blame – for the

musical judgments.

- ABOUT STRAUSS

- Del Mar, Norman: Richard Strauss – A Critical Commentary on His Life and Works (Cornell, 1986)

- Gillam, Bryan: Richard Strauss and His World (Princeton, 1992)

- Krause, Ernst: Richard Strauss – The Man and His Music (Crescendo Publishing, 1969)

- Mailland, J. A.: "Strauss" (article in Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians [1908 edition])

- Marek, George: Richard Strauss – The Life of a Non-Hero (Simon & Schuster, 1967)

- Strauss, Richard: Betrachtungen und Erinnerungen [Views and Memories] in Piero Weiss and Richard Taruskin, Music in the Western World – a History in Documents (Schirmer, 1984)

- ABOUT WILDE

- Wilde, Oscar: The Importance of Being Earnest and Other Plays, introduction by Sylvan Barnet (Signet, 1985) [includes Salome]

- Wilde, Oscar: The Picture of Dorian Gray (preface) (Project Gutenburg eBook, 2008)

- ABOUT SALOME

- Puffitt, Derrick: Richard Strauss's Salome (Cambridge Opera Handbook) (Cambridge University Press, 1989), including the following articles:

- Ayrey, Craig: "Salome's Final Monologue"

- Carpenter, Tethys: "Tonal and Dramatic Structure"

- Holloway, Robin: "Salome – Art or Kitsch?"

- Praz, Marie: "Salome in Literary Tradition"

- Puffitt, Derrick: "Images of Salome"

- Tenschert, Roland: "Strauss as Librettist"

- Williamson, John: "Critical Reception"

- Abert, Anna Amalie: notes to the Karajan LP box (Angel SLBX-3848, 1978)

- Becker, Henry: notes to the Bernstein CD of the finale (DG 431 171-2, 1987)

- Beecham, Sir Thomas: A Mingled Chime (Putnam, 1943)

- Culshaw, John: notes to the Solti LP box (London OSA 1218, 1961)

- Earl of Harewood: notes to "Ljuba Welitsch: The Complete Columbia Recordings" (Sony MH2K 62866, 1997)

- Everding, August: notes to the Bohm LP box (DG 2707 052, 1970)

- Goodall, Howard: The Story of Music From Babylon to the Beatles – How Music Has Shaped Civilization (Pegasus, 2013)

- Mann, William: Richard Strauss – A Critical Study of the Operas (Oxford, 1966)

- Mohr, Richard and Erich Leinsdorf – notes to the Leinsdorf LP box (RCA LSC-7053, 1968)

- Owens, Susan: Aubrey Beardsley's Salome and Satire (Doctoral Thesis, University College, London, 2002)

- Robinson, Frances: notes to the Reiner LP of the final scene (RCA LM-6047, 1956)

- Williamson, John: notes to the Sinopoli CD Box (DG 431 810-2, 1991)

- MISCELLANY

- Carse, Adam: The History of Orchestration (Kagan, Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co., 1925)

- Lang, Paul Henry: Music in Western Civilization (Norton, 1941)

Beardsley: The Burial of Salome |

![]()

Copyright 2015 by Peter Gutmann

copyright © 1998- 2015 Peter Gutmann. All rights reserved.