|

Among her many inscrutable mysteries, my wife often scans the end of a novel before reading it through from the beginning.  But perhaps she's not so different from opera fans, who know their stories by heart, including the endings. The fulfillment is how you get there. But perhaps she's not so different from opera fans, who know their stories by heart, including the endings. The fulfillment is how you get there.

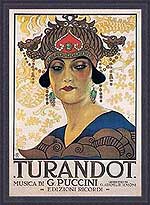

Giacomo Puccini faced that challenge from the other side of the footlights in Turandot, his final opera. He had a gripping plot brimming with passion from lust to torture, riveting characters, an exotic setting, fabulous music and a rousing conclusion, but wrestled for years how to connect them.  He died in 1924, never having figured it out and leaving a gaping hole in his masterwork. As William Berger noted, it's indeed ironic, and perhaps fitting, that the work often cited as the very last in the 325-year line of traditional Italian opera ends not with a bang, nor even a whimper, but a question mark. He died in 1924, never having figured it out and leaving a gaping hole in his masterwork. As William Berger noted, it's indeed ironic, and perhaps fitting, that the work often cited as the very last in the 325-year line of traditional Italian opera ends not with a bang, nor even a whimper, but a question mark.

Perhaps the most telling assessment came from jazzman and populist critic Spike Hughes, who had noted – in 1957! – that as far as the general public was concerned opera had come to a full stop, with all modern work over our head, overly cerebral, and downright dull. In that light, he distinguished Puccini as the last opera composer with any kind of lasting and truly universal popular appeal – his perceived weaknesses of cheap effects, empty bombast, shallow characters and lurid drama that critics and musicians had derided during his lifetime now have emerged as audience-pleasing virtues, essential to maintaining popularity of the genre (or perhaps only in adapting it to the cultural norms of our times). Renowned musicologist Paul Henry Lang agrees by proffering a surprisingly indulgent salute to Puccini's sure instinct for theatrical impact, a wonderful sense of new colors, rich melodic invention, piquant harmonies and clever orchestration, all "decadent drugs which he used to accelerate the blood circulation of his theatre." Yet, Mosco Carner reflects a more balanced view of Puccini as a man of limits and contradictions treading the thin border between genius and mere talent – more heart than mind, intense but shallow characters, stupendous technical accomplishments but weak dramaturgy. Perhaps the most telling assessment came from jazzman and populist critic Spike Hughes, who had noted – in 1957! – that as far as the general public was concerned opera had come to a full stop, with all modern work over our head, overly cerebral, and downright dull. In that light, he distinguished Puccini as the last opera composer with any kind of lasting and truly universal popular appeal – his perceived weaknesses of cheap effects, empty bombast, shallow characters and lurid drama that critics and musicians had derided during his lifetime now have emerged as audience-pleasing virtues, essential to maintaining popularity of the genre (or perhaps only in adapting it to the cultural norms of our times). Renowned musicologist Paul Henry Lang agrees by proffering a surprisingly indulgent salute to Puccini's sure instinct for theatrical impact, a wonderful sense of new colors, rich melodic invention, piquant harmonies and clever orchestration, all "decadent drugs which he used to accelerate the blood circulation of his theatre." Yet, Mosco Carner reflects a more balanced view of Puccini as a man of limits and contradictions treading the thin border between genius and mere talent – more heart than mind, intense but shallow characters, stupendous technical accomplishments but weak dramaturgy.

Born into the fifth generation of a family of opera composers, Puccini frankly admitted that he had little interest in any other genre. He wrote to his multi-talented librettist Guiseppe Adami: "The Almighty touched me with His little finger and said, 'Write for the theatre – mind well, only for the theatre!' And I have obeyed the supreme command." Puccini frankly admitted that he had little interest in any other genre. He wrote to his multi-talented librettist Guiseppe Adami: "The Almighty touched me with His little finger and said, 'Write for the theatre – mind well, only for the theatre!' And I have obeyed the supreme command."

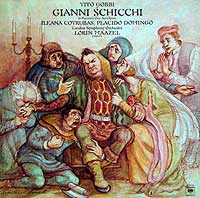

Indeed he did, and in his chosen métier, Puccini was rewarded with an extraordinary decade of success – Manon Lescaut (1893), La Bohème (1896), Tosca (1900) and Madame Butterfly (1904). All profited from his acknowledged strengths while obscuring their dramatic lapses with surging passionate music and remain hugely popular mainstays of the repertory of all major opera houses. Yet, there had been a certain homogeny. His next three operas explored new roads, but at a price of fleeting appeal.  The Girl of the Golden West (1910) was set in the alien world of American cowboys. Next, after delay from the War, came La Rondine ("The Swallow") (1917), a frothy but trite love story among the idle rich. Boldest of all was Il Trittico ("The Triptych") (1918), which consisted of three complementary one-scene operas – Il Tabarro ("The Cloak"), an overwrought verismo melodrama of jealousy and murder, Suor Angelica ("Sister Angelica"), a sentimental all-female religious meditation of remorse and redemption, and Gianni Schicchi, a delightful buffo romp based on a tale from Danté's Divine Comedy in which the cunning title character diverts a wealthy Florentine's estate away from greedy, scheming relatives to his own love-struck daughter. While the first two effectively summed up Puccini's prior unhurried emotion-infused tragedies, Schicchi, aside from a single gorgeous but largely gratuitous aria, placed lean music deftly at the service of advancing a fast-moving and intricate plot and rose to an uncharacteristically understated and genuinely touching ending, as the title character steps forward to ask the audience for forgiveness for his deceitful ploy and to signal their approval with applause. Jörgen Maehder aptly notes that Il Trittico's vastly different tragic, romantic and comic styles prefigured the integration of these elements in Puccini's next and final work. The Girl of the Golden West (1910) was set in the alien world of American cowboys. Next, after delay from the War, came La Rondine ("The Swallow") (1917), a frothy but trite love story among the idle rich. Boldest of all was Il Trittico ("The Triptych") (1918), which consisted of three complementary one-scene operas – Il Tabarro ("The Cloak"), an overwrought verismo melodrama of jealousy and murder, Suor Angelica ("Sister Angelica"), a sentimental all-female religious meditation of remorse and redemption, and Gianni Schicchi, a delightful buffo romp based on a tale from Danté's Divine Comedy in which the cunning title character diverts a wealthy Florentine's estate away from greedy, scheming relatives to his own love-struck daughter. While the first two effectively summed up Puccini's prior unhurried emotion-infused tragedies, Schicchi, aside from a single gorgeous but largely gratuitous aria, placed lean music deftly at the service of advancing a fast-moving and intricate plot and rose to an uncharacteristically understated and genuinely touching ending, as the title character steps forward to ask the audience for forgiveness for his deceitful ploy and to signal their approval with applause. Jörgen Maehder aptly notes that Il Trittico's vastly different tragic, romantic and comic styles prefigured the integration of these elements in Puccini's next and final work.

Puccini was always exacting in his choice of librettos (indeed, his lifetime output was only ten operas), and toyed with many projects before finding another worth pursuing. He finally found it when his friend, Renato Simoni, suggested Turandot. The basic tale of a protagonist having to solve riddles to save his life dates back through Arab legend to the Greek myth of Œdipus and the Sphinx. Simoni had written a play about Carlo Gozzi, who had published Turandotte in 1721 as one of 10 faibe ("fables"). In reaction to the emerging trend of realism in Venetian theatre (and to save the livelihood of his troupe), Gozzi's version of the tale combined fantasy, caricature, stock characters, extravagant sets, improvisation and slapstick. Although Puccini may have seen a Max Reinhardt 1911 Berlin revival of the Gozzi play, his direct source was an Italian translation of an 1802 German adaptation by Frederich Schiller, which Simoni lent him. Puccini was always exacting in his choice of librettos (indeed, his lifetime output was only ten operas), and toyed with many projects before finding another worth pursuing. He finally found it when his friend, Renato Simoni, suggested Turandot. The basic tale of a protagonist having to solve riddles to save his life dates back through Arab legend to the Greek myth of Œdipus and the Sphinx. Simoni had written a play about Carlo Gozzi, who had published Turandotte in 1721 as one of 10 faibe ("fables"). In reaction to the emerging trend of realism in Venetian theatre (and to save the livelihood of his troupe), Gozzi's version of the tale combined fantasy, caricature, stock characters, extravagant sets, improvisation and slapstick. Although Puccini may have seen a Max Reinhardt 1911 Berlin revival of the Gozzi play, his direct source was an Italian translation of an 1802 German adaptation by Frederich Schiller, which Simoni lent him.

Of many prior operatic versions of Gozzi's fable, Puccini might have been familiar with two.  One of his teachers, Antonio Bazzini, had composed a Turandot in 1867, but it was a failure, only performed once and never published. A more important precedent was by Ferruccio Busoni, which began as incidental music to the Reinhardt staging and was expanded to a 75-minute opera, but with only a veneer of orientalism over a core of essentially neoclassical music, stylized emotions and a chamber texture. One of his teachers, Antonio Bazzini, had composed a Turandot in 1867, but it was a failure, only performed once and never published. A more important precedent was by Ferruccio Busoni, which began as incidental music to the Reinhardt staging and was expanded to a 75-minute opera, but with only a veneer of orientalism over a core of essentially neoclassical music, stylized emotions and a chamber texture.

The basic plot is common to these and other versions of the tale. The captivating but man-hating princess Turandot requires her suitors to solve three riddles. The cost of failure is death, which many have already suffered. Enthralled by her irresistible allure and despite warnings from his elders, a fugitive prince manages to answer all three of her enigmas in a splendid ceremonial and intensely dramatic confrontation. Horrified at the prospect of yielding to him, Turandot prepares to take her own life, but the prince propounds a riddle of his own – he will die if she can discover his name by daybreak. While the treatments diverge somewhat at this point, the name ultimately is revealed but Turandot, astounded by the depth of the prince's love, embraces him and renounces her vicious past.

The fundamental problem with this plot is obvious and severe – why would a cold-blooded murderess suddenly change so completely? To Gozzi it hardly mattered, since his tale was a fantasy in which plausibility only would have ruined the sense of magic. Busoni, too, rejected logical motivation – he felt that "a love duet on the public stage is ridiculous," that sung words were a hindrance to truth, and that plots must be incredible and improbable from the start. But Puccini's characters were full-blooded emotive beings who moved audiences with the depth and ardency of their feelings. As he developed Turandot, the problem of the princess's transformation only deepened. Indeed, it was compounded by an omnipresent chorus, which has to turn literally overnight from a mindless bloodthirsty mob into a warmly supportive throng singing blissful praises of love.

Part of Puccini's attraction to the tale may have been an idealization of his own bizarre love life. Although professionally demanding of his colleagues, Puccini was charming, gentle, kind and modest. Yet he was a hedonist, driven by sexual desire far more than affection or spiritual attachment. In 1885 he eloped and set up house with Elvira Gemignani, a married woman, wedding her only after her husband's death 19 years later. Their stormy life together was hardly one of marital bliss, and matters were worsened by Elvira's insane jealousy that led her to accuse one of their maids of an affair and then hound her to suicide (a groundless charge, as an autopsy proved the servant had died a virgin). The public scandal that ensued only magnified the nagging hostility Puccini constantly faced from living in sin in a devoutly Catholic Italy. Puccini's compulsive attraction to Elvira under such knotty circumstances bears some psychological relationship to that of the prince and Turandot.

Aside from the basic plot, Puccini retained another vital facet of the Gozzi original.

La Scala costume designs for the three Masks |

His three characters Ping, Pang and Pong, who appear as a quirky mini-chorus of observers to comment on the action and test the central characters' thoughts and motivations, are derived from Gozzi's "masks." As an essential component of his commedia dell'arte formula, Gozzi's actors wore half-masks to identify their stock roles and submerge their individuality. Puccini retained them as an emblem of Italian tradition and to mediate his work between comic fantasy and earthy realism, much as Shakespeare had done with his minor characters. Puccini clearly considered his Masks a key element, giving their solo turns nearly one-sixth of the entire running time of the opera with, as Carner notes, distinctive music of skipping intervals, jerky rhythms and dry orchestration that invokes puppets on strings.

Puccini's music is an extraordinary blend of twentieth century and oriental influences, ranging from parallel fourths and pentatonic scales to bitonality and tone clusters, all of which he readily absorbed and put to his own use. The adventure begins at the very outset in which a sharp dissonant chord of simultaneous c-sharp and d-natural triads symbolizes and portends the plot's conflict of personalities struggling for dominance. Overall, his music convincingly evokes the Chinese setting, as it should – eight of his principal themes are authentic temple music, national hymns and folk songs – especially the haunting "Mo-Li-Hua" ("jasmine flower") melody that pervades the work in various forms and which was well-known throughout Europe at the time. Puccini's music is an extraordinary blend of twentieth century and oriental influences, ranging from parallel fourths and pentatonic scales to bitonality and tone clusters, all of which he readily absorbed and put to his own use. The adventure begins at the very outset in which a sharp dissonant chord of simultaneous c-sharp and d-natural triads symbolizes and portends the plot's conflict of personalities struggling for dominance. Overall, his music convincingly evokes the Chinese setting, as it should – eight of his principal themes are authentic temple music, national hymns and folk songs – especially the haunting "Mo-Li-Hua" ("jasmine flower") melody that pervades the work in various forms and which was well-known throughout Europe at the time.

The "Mo-Li-Hua" theme |

Some had been published in an 1884 book by J. A. Aalst on Chinese music; Adami and Puccini heard others in August 1920 on a music box belonging to a Baron Fassini, which William Weaver tracked down and verified in 1974 through the baron's widow.

Puccini was consumed with enthusiasm for his project, excitedly referring to his creative fever as "a kind of illness, an over-excitation of every fiber and every atom," and proclaiming that he was "savoring above all the clear and moving humanity that is in this story, full of poetry and special perfume." The first two acts came relatively easily and were mostly finished by July 1921.  The first is often described as symphonic, and indeed the development is organic and continuous, the episodes united by the chorus which assumes an unprecedented dominant role, smoothly integrating a mandarin's pronouncement of Turandot's challenge, the main characters' introduction, the prince's infatuation, a prior suitor's execution, the Masks' attempts to intervene, a warning from the ghosts of past victims, and the pleas of Timur (the prince's exiled father), all with a near-continuous flow of music. As with much of the opera, even apparently simple matters have disturbing overtones – among the most extraordinary moments is a lovely paean to the rising moon but the crowd's seemingly candid salute to nature, heightened by a charming children's chorus, is tinged with blood-lust, as the prince of Persia is to be beheaded once the moon appears. Indeed, there's a constant divide between the buoyant, invigorating music and the pitiless, grisly text. The end of Act I is dazzling, as the unknown Prince, his compulsion invoked by a relentlessly building motif, summons Turandot and then remains transfixed, staring immobile at his nemesis while a clipped phrase from her motif pounds home the overpowering allure and mortal danger he now faces. It's the operatic equivalent of a cinematic freeze-frame, forcing us both to focus on the immediate situation and to look beyond the deliberately static physical staging to ponder the psychological implications of an intractable confrontation. The first is often described as symphonic, and indeed the development is organic and continuous, the episodes united by the chorus which assumes an unprecedented dominant role, smoothly integrating a mandarin's pronouncement of Turandot's challenge, the main characters' introduction, the prince's infatuation, a prior suitor's execution, the Masks' attempts to intervene, a warning from the ghosts of past victims, and the pleas of Timur (the prince's exiled father), all with a near-continuous flow of music. As with much of the opera, even apparently simple matters have disturbing overtones – among the most extraordinary moments is a lovely paean to the rising moon but the crowd's seemingly candid salute to nature, heightened by a charming children's chorus, is tinged with blood-lust, as the prince of Persia is to be beheaded once the moon appears. Indeed, there's a constant divide between the buoyant, invigorating music and the pitiless, grisly text. The end of Act I is dazzling, as the unknown Prince, his compulsion invoked by a relentlessly building motif, summons Turandot and then remains transfixed, staring immobile at his nemesis while a clipped phrase from her motif pounds home the overpowering allure and mortal danger he now faces. It's the operatic equivalent of a cinematic freeze-frame, forcing us both to focus on the immediate situation and to look beyond the deliberately static physical staging to ponder the psychological implications of an intractable confrontation.

Act II opens with a ten-minute scene

The Act II riddle scene at La Scala - set by Nicola Benois |

with the Masks that may seem dramatically irrelevant but serves to defuse the tension of the Act I close before the main action resumes. The rapidly changing mood is a mixture of comic relief, cynicism, nostalgia, and tenderness. Hughes considers that "nowhere in all of Puccini is such fine music and invention so powerfully concentrated." When the crowd returns, Turandot explains in the commanding aria "In questa reggia" ("In this palace") that her vengeance against men stems from the rape and murder of a forebear. Amazingly, nearly half the opera has gone by before its title character is heard (nor even glimpsed more than fleetingly). (Among precedents, only Beethoven had dared to keep his male lead buried (literally) throughout the first half of his Fidelio.) There ensues the great riddle scene, in which the prince struggles to solve Turandot's three enigmas using the same music with which she propounds them, a neat symbolic means of conquest with her own weapons, and then presents his own challenge. (The enigmas changed with each new version – thus, Gozzi's were sun, year and the lion of Adria; Schiller's were year, eye and plow (although reportedly he would change them for each local production); and Busoni's were man's intellect, fashion and art. Although it's hard to attach any significance to most of those specific answers, Adami/Simoni's, in clear reference to the title character, were hope, blood and Turandot.)

The key plot point of the final act – how Turandot discovers the prince's name – evolved considerably among the variants of the Turnadot tale and gave rise to the third key role in the opera. After three characters try to cajole the prince himself into revealing his name, Gozzi has Adelma, formerly a princess and now a vengeful slave, trick him into uttering it, thus betraying the prince for having snubbed her affections. Busoni has a more crafty Adelma trade her secret for her own freedom. Adami and Simoni created a wholly new and hugely appealing character – Liù, a slave girl enamored of the prince, whom Turandot's henchmen torture and who then kills herself to preserve the secret, after which the prince himself tells Turandot his name in supreme confidence that his love will conquer all.

Liù's defiance and demise in the final act comprises the last portion of the opera that Puccini could complete. The entire sequence is a deeply moving ostinato (repeated motif) that is both mournful and inevitable, beginning in tenderness, powerfully building to the moment of her suicide, and subsiding into soft regret. The nocturnal opening scene of Act III is equally striking – a surrealistic affirmation of Puccini's mastery of mood as people whisper Turandot's command that none may sleep until the prince's identity is revealed. The prince himself wanders in and turns his musing over the phrase into one of the most heady arias in all of Italian opera, "Nessun dorma."

The end of that aria raises two issues. First, while Williams Ashworth and Harold Powers consider Turandot essentially a numbers opera (consisting of set pieces), they note that the music is continuous, which at this juncture poses an especially severe problem for performance – "Nessun dorma" ends on a ringing triumphant note that invariably invites ecstatic applause, yet the final phrase melds right into the next number with a lovely harmonic transition that even a mild ovation entirely obscures. (There's no easy solution – in the live recordings noted below, Gavazzani forges ahead and smothers the transition along with the next several lines, while Stokowski waits for the ovation to subside and then resumes, shattering the continuity.)  Second, the penultimate note is a thrilling high b, but it's only written as a grace note. Yet few tenors can resist distending it into ear-ringing proof of their lung-power – Pavarotti, in the highly-acclaimed 1973 Decca recording, holds it for a full six seconds. The effect is thrilling for sure, but not necessarily Puccini. Or is it? As David Hamilton notes, early records by artists who created roles in close conjunction with composers often depart from embellishments in the score, not necessarily in violation of the composer's intention but rather using an interpretive license that may have been assumed at the time. That is, if Puccini knew that every tenor tackling the role would tend to stretch the note, and that any conductor would accommodate them, why bother to clutter the score with redundant notation that would distort the musical sense? Second, the penultimate note is a thrilling high b, but it's only written as a grace note. Yet few tenors can resist distending it into ear-ringing proof of their lung-power – Pavarotti, in the highly-acclaimed 1973 Decca recording, holds it for a full six seconds. The effect is thrilling for sure, but not necessarily Puccini. Or is it? As David Hamilton notes, early records by artists who created roles in close conjunction with composers often depart from embellishments in the score, not necessarily in violation of the composer's intention but rather using an interpretive license that may have been assumed at the time. That is, if Puccini knew that every tenor tackling the role would tend to stretch the note, and that any conductor would accommodate them, why bother to clutter the score with redundant notation that would distort the musical sense?

Puccini's struggle with the conclusion of Turandot generated enough anguish for a verismo opera of its own. Tensions soon arose with his librettists – he was constantly frustrated over their delays in providing revised material, while they found him impossible to satisfy. Puccini's struggle with the conclusion of Turandot generated enough anguish for a verismo opera of its own. Tensions soon arose with his librettists – he was constantly frustrated over their delays in providing revised material, while they found him impossible to satisfy.

Simoni, Puccini and Adami |

(In fairness, they both had many other professional obligations – Simoni was a busy editor and Italy's foremost drama critic while Adami, who had written the librettos to Puccini's La Rondine and Il Tabarro, was a film director and author who wrote seven plays and five other librettos while working on Turandot.) Puccini's correspondence is full of enthusiastic praise of their work followed by rejection. From a purely literary standpoint, the problem seemed insoluble, as the Turandot character they had created was intensely aloof, proud and cruel – indeed, right up to the end she wholly ignores Liù's supreme sacrifice – yet somehow amorous passion must erupt and she must suddenly and wholeheartedly yield to the prince. But operas never work through their words alone, and Puccini foresaw a purely musical solution – a duet in which she would melt from an abstract icy legend into a warm, vibrant human being whose love was so vast that it would envelop everyone on stage. He envisioned it as the nodal point: "All that is beautiful and vivid in the drama converges on it."

Puccini described his conception in numerous letters to Adami throughout the period of Turandot's gestation. As early as 1921, he proclaimed that the duet "must be grand, bold, unforeseen" and that it "must cling to the fantastic to the limit."  "It must be something great, audacious and unexpected, and not leave things simply as they are … . It must be a great duet – These two beings, who stand, so to speak, outside the world, are transformed into humans through love and this love must take possession of everybody on the stage in an orchestral peroration." Even the set itself would yield "fantastic apparitions" that would embroider the marble with flowers. "It must be something great, audacious and unexpected, and not leave things simply as they are … . It must be a great duet – These two beings, who stand, so to speak, outside the world, are transformed into humans through love and this love must take possession of everybody on the stage in an orchestral peroration." Even the set itself would yield "fantastic apparitions" that would embroider the marble with flowers.

Puccini's ordeal wasn't purely artistic. In March 1924 he first mentioned a new and far different problem – a pain in his throat. After consulting five specialists who issued a diagnosis of cancer (which he may never have been told), he agreed to go to Brussels for experimental radiation treatment. On October 8, he wrote Adami that he had received Simoni's latest attempt at the crucial exchange between Turandot and the Prince, which he dubbed "truly beautiful" and declared that the new words "complete and justify the duet." Typically, though, only two days later he said it needed more work. On October 22, he wrote that it still didn't connect with Liù's words and implied that he knew how he would work it all out and planned to finish the opera when he returned from Brussels.

He never did. The treatment consisted of a course of x-rays followed by radium needles inserted into the tumor for a week. The first stage went well, but on the fourth day of enduring the needles Puccini suffered a heart attack. He died the next morning, taking with him the elusive ending of the opera with which he had struggled for so many years.

Puccini's death left his publisher, Ricordi, with a valuable property that somehow needed to be completed. At first, they suggested Francesco Zandonai, a brilliant orchestrator, but Puccini's son Tonio felt that Zandonai's fame would divert attention. They settled on Franco Alfano, who shared Puccini's blend of traditional Italian and modern styles and whose 1921 opera La leggenda di Sacùntala had an equally exotic setting. Puccini had taken 36 pages of fragmentary themes and notes with him to Brussels. Later scholars have struggled to decipher them and are especially intrigued by a cryptic message: "Poi Tristano" ("then Tristan"). Jörgen Maehder, who published an extensive comparative analysis of the sketches and Alfano's completion, suggests that it could refer to Puccini's desire to emulate Wagner's opera in some way, but how? – in a general thematic sense of its redemptive power of love, through its characteristic chromatic music, or perhaps with an actual quotation? Puccini's death left his publisher, Ricordi, with a valuable property that somehow needed to be completed. At first, they suggested Francesco Zandonai, a brilliant orchestrator, but Puccini's son Tonio felt that Zandonai's fame would divert attention. They settled on Franco Alfano, who shared Puccini's blend of traditional Italian and modern styles and whose 1921 opera La leggenda di Sacùntala had an equally exotic setting. Puccini had taken 36 pages of fragmentary themes and notes with him to Brussels. Later scholars have struggled to decipher them and are especially intrigued by a cryptic message: "Poi Tristano" ("then Tristan"). Jörgen Maehder, who published an extensive comparative analysis of the sketches and Alfano's completion, suggests that it could refer to Puccini's desire to emulate Wagner's opera in some way, but how? – in a general thematic sense of its redemptive power of love, through its characteristic chromatic music, or perhaps with an actual quotation?

In any event, Alfano largely ignored Puccini's sketches and instead used themes from prior portions of the opera, beginning with transforming the gentle ostinato of Liù's funeral cortege that brought the preceding scene to a hushed close into a brash outburst that creates a jarringly abrupt transition, abetted by his far more basic orchestration. (Indeed, except for this appropriation of her theme in a defiant and disdainful context that seems to disregard her nature, poor Liù is entirely discarded, never to be mentioned again, and so the selfless sacrifice of the most appealing character in the entire opera becomes utterly bereft of significance.)  After several minutes of barking their intractable convictions at each other, in the words of the libretto's stage direction: After several minutes of barking their intractable convictions at each other, in the words of the libretto's stage direction:

As he speaks, the Unknown Prince, filled with the sense of his right and with his passion, seizes Turandot in his arms and kisses her in a frenzy. Carried away, Turandot has no more resistance, no more strength, no more will power. This unbelievable contact has transfigured her. In a pleading, almost childlike voice, she now murmurs: "What has become of me? I'm lost!"

As Turandot instantly becomes a quivering blob in the Prince's arms, the music turns suitably soft and sweet, primed by a wordless offstage women's chorus, leading to Turandot's second aria, "Il primo pianto" ("My first kiss"), in which she claims to have known from the outset that the Prince would win her. Flush with victory, the Prince proclaims his name – Calaf. Amid much blaring fanfare, Turandot summons her court to announce that she knows the Prince's name – it is love! Whereupon, to the irrelevant but thrilling theme of "Nessun dorma," the very crowd that only moments before had clamored to force Liù to reveal the prince's name, and whose only concern over her death was that her ghost might haunt them, bursts into a rousing hymn to sun, life, eternity and, of course, love. Both psychologically and dramatically, the irrational and abrupt conversion of Turandot and her entire court is patently absurd, if not downright idiotic. (Consistent with their outlooks, Gozzi's play ended with Turandot seeking forgiveness for her past and thus transforming the social order; Busoni's wraps up somewhat facetiously with a wedding dance.) Yet the undeniable fact that it all works musically is supreme proof of opera's potent ability to suspend disbelief and transcend the world as we know it.

Critical reaction to Alfano's work has been largely disparaging.

Franco Alfano |

Admittedly, he had a tough, if not impossible, assignment – realizing in months what the greatest opera composer of his time couldn't achieve in four years. Perhaps the most charitable view is from Teodoro Celli, who examined Puccini's sketches and felt that they "can only inspire us in admiration for what Alfano managed to achieve – not only an expert's great mastery but also with extreme respect and loyalty to Puccini's intentions." Most other assessments have ranged from regret to hostility. George Marek notes that had Puccini lived "not only would he have completed it but would have clarified Turandot's character, adjusted balances, made corrections, shaping and smoothing – the creative improvements in detail required to make a masterpiece." Carner felt that even if the elements were Puccini's the result lacked inspiration and was a dramatic and musical failure. He further decried Alfano's perceptible break in style toward rigid vocal declamation, and suggested that a symphonic interlude would have depicted the tensions in Turandot's heart. Taking a feminist view, Catherine Clément sees Turandot's capitulation as symbolic of women's repression and more worthy of musical comedy than opera. Perhaps the harshest judgment is from Spike Hughes, who calls Alfano's work "monstrously banal and inept" and (literally following Toscanini's footsteps) claims that after hearing it once he always leaves the theatre after Liù's death.

2001 brought a striking advance with the publication of a new ending by Luciano Berio (heard on a Puccini Discoveries Decca CD led by Riccardo Chailly). A modernist with a wide-ranging interest in reworking music of the past, Berio abridged the libretto to the portions for which Puccini had left musical sketches, synthesized Puccini's themes to fashion an apt musical culmination, and extended Puccini’s harmonies into a new realm as if searching afar for new meaning. Consistent with Carner's suggestion, in lieu of the sudden makeshift surge of passion in which Alfano has Calaf seize Turandot to kiss her, Berio crafts a 2½ minute orchestral interlude in which their conflicting, pained and tempestuous emotions buffet about, work their way through and subside into an exhausted, cautious concord. Turandot’s final line, when she announces Calaf’s name to the crowd, is not declaimed with triumphant glory but profferred in hushed tones accompanied by the piercing dissonance of uncertainty. While the psychology of her transformation from vicious murderer to humane lover still remains dubious, Berio foregoes the cheap (yet undeniably potent) thrill of Alfano’s ecstatic but unmotivated Hollywood ending for a far more nuanced and credible finish that leaves Calaf and Turandot on the threshold of discovering both each other and themselves, as their fanatical power struggle evolves into an exploration of human intimacy – tentative, yet as confusing and promising as life itself in all its unfathomable complexity. Even the chorus becomes hushed and then falls silent as the orchestra softly trails off into a vast psychic unknown, as if perplexed over the challenging implications of the social upheaval and its promise of a wholly new future.  True, there’s a disconnect with Puccini’s late Romantic style, but it seems far more inspired and thematically appropriate than Alfano’s crude and insipid bombast. While critical reaction has been mixed, to my ears it’s a deeply moving and brilliant, if not definitive, solution to the ultimate riddle of Turandot that Puccini left at his death. True, there’s a disconnect with Puccini’s late Romantic style, but it seems far more inspired and thematically appropriate than Alfano’s crude and insipid bombast. While critical reaction has been mixed, to my ears it’s a deeply moving and brilliant, if not definitive, solution to the ultimate riddle of Turandot that Puccini left at his death.

The gala premiere took place at La Scala on April 25, 1926, directed by Arturo Toscanini, the most famous opera conductor in the world. Mussolini was to have attended, but cancelled when Toscanini refused to open with the fascist anthem. Right after Liu's cortege left the stage Toscanini ended the performance and addressed the audience, saying something to the effect that here the opera ends because here the composer died. (The exact words differ in various accounts, but in any event Toscanini was being figurative, since the preceding section had been written in 1921. Accounts also differ as to whether Toscanini led the remainder in subsequent performances or whether he turned Alfano's completion over to assistants.) The gala premiere took place at La Scala on April 25, 1926, directed by Arturo Toscanini, the most famous opera conductor in the world. Mussolini was to have attended, but cancelled when Toscanini refused to open with the fascist anthem. Right after Liu's cortege left the stage Toscanini ended the performance and addressed the audience, saying something to the effect that here the opera ends because here the composer died. (The exact words differ in various accounts, but in any event Toscanini was being figurative, since the preceding section had been written in 1921. Accounts also differ as to whether Toscanini led the remainder in subsequent performances or whether he turned Alfano's completion over to assistants.)

Although they had an erratic relationship, Toscanini was closely involved in the creation of Turandot, and the composer often acclaimed him as the greatest conductor of his work. (Although Puccini actively participated in the production of his operas, he had no desire to conduct them.) Puccini had entrusted Toscanini with the world premiere of La Bohème. When Toscanini led a 30th anniversary production of Manon Lescaut in 1923, Puccini praised his poetic feeling and expression, declaring: "You have given me the greatest satisfaction of my life." Puccini wanted Toscanini to introduce Turandot, writing to a friend: "Toscanini is really the best man in the world now as a conductor because he has everything – soul, poetry, flexibility, discipline, dash, refinement, sense of drama – all in all a real miracle."

Rosa Raisa, the first Turandot |

Following a misunderstanding and reconciliation (Puccini had snuck into a rehearsal of a new Boito opera for which Toscanini had sought absolute privacy), Toscanini visited Puccini in early October 1924, just before the composer's fateful trip to Brussels, to hear Turandot in anticipation of its premiere the next Spring and thought it all excellent – except for the final duet in its emerging form, a judgment shared by the frustrated composer. (Although this may be apocryphal, Puccini reportedly predicted to Toscanini that he would not live to finish Turandot and that the premiere would require an announcement like the one Toscanini ultimately made.)

The first full recording of Turandot wasn't produced until a dozen years after its premiere. (By then, there were four complete Toscas, four Butterflies and three Bohèmes, although admittedly they all had substantial head starts). In the meantime, arias were recorded. Puccini reportedly had written the major roles with specific singers in mind (Maria Jeritza as Turandot, Gilda Della Razza as Liù and either Beniamino Gigli or Giocomo Lauri-Volpe as the prince). Yet, none was available for the long-delayed premiere and in any event Toscanini wanted his own cast. Of his leads, only Maria Zamboni as Liù recorded an aria from her role. (The powerful tenor Miguel Flita, the first prince, dropped the part immediately, although his interpretation must have been exquisite, at least judging from the breathtaking diminuendos in his 1923 "La donna e mobile." Rosa Raisa, although highly acclaimed as the first Turandot, never made any records of her role.) In 1926 Zamboni cut in Milan "Tu che di gel sei cinta," her heart-rending final words in which she explains her love for the prince before suddenly taking her life. Her young, sweet voice slides between notes yet trembles with feeling, embellishing with emotional gasps and adding an emphatic penultimate note. The first full recording of Turandot wasn't produced until a dozen years after its premiere. (By then, there were four complete Toscas, four Butterflies and three Bohèmes, although admittedly they all had substantial head starts). In the meantime, arias were recorded. Puccini reportedly had written the major roles with specific singers in mind (Maria Jeritza as Turandot, Gilda Della Razza as Liù and either Beniamino Gigli or Giocomo Lauri-Volpe as the prince). Yet, none was available for the long-delayed premiere and in any event Toscanini wanted his own cast. Of his leads, only Maria Zamboni as Liù recorded an aria from her role. (The powerful tenor Miguel Flita, the first prince, dropped the part immediately, although his interpretation must have been exquisite, at least judging from the breathtaking diminuendos in his 1923 "La donna e mobile." Rosa Raisa, although highly acclaimed as the first Turandot, never made any records of her role.) In 1926 Zamboni cut in Milan "Tu che di gel sei cinta," her heart-rending final words in which she explains her love for the prince before suddenly taking her life. Her young, sweet voice slides between notes yet trembles with feeling, embellishing with emotional gasps and adding an emphatic penultimate note.

Eva Turner as Turandot |

Even in isolation, it's a deeply touching portrayal of a scared but resolute waif. The only other creators' record came the following May, when Aristide Baracchi, Emilio Venturini and Giuseppe Nessi, the three original Masks, cut a double-sided Fonotipia disc of the opening scene of Act II (but shorn of the lyric middle section where they long for retirement). Their convincing characterizations are abetted by their distinctive voices, as Pong's tenor is offset by Ping's rich baritone and Pang's nasal bleating.

The most famous of the first generation of Turandots was Eva Turner, who recorded "In questa reggia" twice for Columbia in 1928 – in April in Milan and in June in London. (The interpretations are nearly identical, but the latter gains from Turner singing both hers and the prince's climactic phrases, which makes little dramatic sense but generates an irresistible musical impact.) Critics generally faulted her for a lack of warmth and for singing consistently too loud, but that was hardly a problem for this particular role. Personally coached by Alfano, she sang the role to great acclaim for over 20 years. In 1960, she wrote that others had placed too much emphasis on Turandot's cruelty; to her, the overriding trait should be fear, terrified once she meets the prince that her self-imposed boundaries are about to crumble. Turner's performance is gripping in its sharp, effortless power, her climactic high C sounding natural without the slightest strain or self-consciousness. Yet, she projects just a hint of vulnerability, as her imperious instincts battle against her sense of foreboding and vulnerability.

The first complete Turandot was recorded in Turin in 1938 by Cetra. Perhaps in keeping with the immortal nature of the opera, all three leads had astounding longevity – Francesco Merli (Calaf) lived to 89, Genevieve Cigna (Turandot) lived to 101 and as of this writing (April 2014) Magda Olivero (Liù) is still among us at 104!  All were dominant La Scala stars of the time and turn in fine performances, well-characterized without preening for attention – a true team effort, judiciously paced by Franco Ghione, who had worked as Toscanini's assistant and thus perhaps represents the way the Maestro, who never recorded his interpretation, had shaped the premiere. One telling moment – that thrilling penultimate grace note that ends "Nessun dorma" for once is just that, taken in proper time and promptly dropped. Indeed, the score is strictly observed throughout – except for omitting the entire "Il primo pianto" aria from the finale, which admittedly gets through the feeble outcome more efficiently. (Although included in the printed score and most recordings, the aria is often bypassed in live performances, including the two noted below.) The chorus is a bit ragged, especially in the more complex passages, but this serves to add a human element to its otherwise cruel and disembodied role. Ping, Pang and Pong (Gino del Signore, Adelio Zagonara and Afro Poli) sound somewhat confusing without differentiated voices, a necessity for monaural audio recordings without the spatial or visual clues of stereo or staging. Artistically, this may be the most authentic Turandot on record, but the congested sound does tend to obscure many felicities of the orchestration. One bizarre trait, though – the gong with which the prince summons Turandot sounds like the "bing" of an office elevator and evokes a smirk rather than the terror of the deep, resonating portent used on nearly all the other recordings (although the one heard in the Callas recording – like two garbage can lids smashing together – is barely better). All were dominant La Scala stars of the time and turn in fine performances, well-characterized without preening for attention – a true team effort, judiciously paced by Franco Ghione, who had worked as Toscanini's assistant and thus perhaps represents the way the Maestro, who never recorded his interpretation, had shaped the premiere. One telling moment – that thrilling penultimate grace note that ends "Nessun dorma" for once is just that, taken in proper time and promptly dropped. Indeed, the score is strictly observed throughout – except for omitting the entire "Il primo pianto" aria from the finale, which admittedly gets through the feeble outcome more efficiently. (Although included in the printed score and most recordings, the aria is often bypassed in live performances, including the two noted below.) The chorus is a bit ragged, especially in the more complex passages, but this serves to add a human element to its otherwise cruel and disembodied role. Ping, Pang and Pong (Gino del Signore, Adelio Zagonara and Afro Poli) sound somewhat confusing without differentiated voices, a necessity for monaural audio recordings without the spatial or visual clues of stereo or staging. Artistically, this may be the most authentic Turandot on record, but the congested sound does tend to obscure many felicities of the orchestration. One bizarre trait, though – the gong with which the prince summons Turandot sounds like the "bing" of an office elevator and evokes a smirk rather than the terror of the deep, resonating portent used on nearly all the other recordings (although the one heard in the Callas recording – like two garbage can lids smashing together – is barely better).

The Cetra Turandot is of vast importance, both historically and artistically. Of the many studio recordings of Turandot that followed, I've selected five that seem to have attracted the greatest critical attention over the years. The Cetra Turandot is of vast importance, both historically and artistically. Of the many studio recordings of Turandot that followed, I've selected five that seem to have attracted the greatest critical attention over the years.

The first was made in 1955 by Decca. (Although later released in stereo with a fancier red cover, my comments are based on the original London mono US LP edition.)  The sound is well-balanced and detailed, affording a welcome opportunity to savor the many facets of the exceptionally active orchestration, not only in accompanying the singing with complex figurations but in rendering with crystalline clarity the impressionistic atmosphere that introduces the flitting nocturnal fears of Act III. Although the overall timings of each act are virtually identical to Ghione's, the ceremonial portions tend to be more deliberate and their climaxes somewhat repressed, draining the sung sentiments of much of their glory and lending a pervasive feeling of inevitability to a sad and meaningless ritual. Ingrid Borkh (Turnadot) has a beautiful, rich voice that mesmerizes rather than startles, and Mario del Monaco (Calaf) sounds like a bold, reckless, virile hero. Both are well-suited to their roles, and the closely-miked pick-up registers all the nuance with which they enrich their interpretations, lending an arresting intensity to their efforts to outdo each other in the climax to "In questa reggia." Perhaps most fascinating is Renata Tebaldi as Liù. At first she sounds a bit too matronly for the role, and yet it really does demand a degree of musical sophistication that chafes against an image of a fresh, star-struck adolescent follower. Indeed this role may be the most difficult in the opera, as a credible image treads a thin line between frail, bewildered, innocent ingénue and intrepid, mature, principled moralist. The sound is well-balanced and detailed, affording a welcome opportunity to savor the many facets of the exceptionally active orchestration, not only in accompanying the singing with complex figurations but in rendering with crystalline clarity the impressionistic atmosphere that introduces the flitting nocturnal fears of Act III. Although the overall timings of each act are virtually identical to Ghione's, the ceremonial portions tend to be more deliberate and their climaxes somewhat repressed, draining the sung sentiments of much of their glory and lending a pervasive feeling of inevitability to a sad and meaningless ritual. Ingrid Borkh (Turnadot) has a beautiful, rich voice that mesmerizes rather than startles, and Mario del Monaco (Calaf) sounds like a bold, reckless, virile hero. Both are well-suited to their roles, and the closely-miked pick-up registers all the nuance with which they enrich their interpretations, lending an arresting intensity to their efforts to outdo each other in the climax to "In questa reggia." Perhaps most fascinating is Renata Tebaldi as Liù. At first she sounds a bit too matronly for the role, and yet it really does demand a degree of musical sophistication that chafes against an image of a fresh, star-struck adolescent follower. Indeed this role may be the most difficult in the opera, as a credible image treads a thin line between frail, bewildered, innocent ingénue and intrepid, mature, principled moralist.

1957 brought a La Scala set starring Maria Callas. (Curiously, despite the date it was recorded only monaurally.) As with all her recordings of complete operas, the focus of attention is Callas herself. That poses a special challenge here. While it's hardly unusual for operas (and plays) to begin with secondary characters setting the stage for the leads' entrances, Turandot is first heard only on the fourth of the original six LP sides, so the entire first half depends upon the supporting cast and orchestra, which I find far stronger than most commenters lead us to expect – the first three sides aren't mere vamping until La Divina arrives.   At least judging from an original Angel LP set, the recording is somewhat blurred and thin, the instrumental ensemble sounds more like a pit band than a lush symphony orchestra, and the mix favors the voices, all evoking an appropriate atmosphere of the theatre. Conductor Tullio Serafin takes a more flexible, expressive approach than his predecessors and adds some wonderful touches – the Persian prince's single phrase that's cut off (along with his head) is strangulated and for once horrifyingly convincing. Elizabeth Schwartzkopf sings Liù with great expression and tenderness, as one would expect from an accomplished lieder singer. The Masks (Piero de Palma, Renato Ercolani and Mario Borriello) interact wonderfully, painting an especially moving portrait of bureaucrats stuck in a rut of supporting a regime in which they lost faith long ago. (The sole disappointment among the supporting cast is a whiny, bleating Altoum, Turandot's father, more a caricature of age than feeble and sad.) Rising tenor Eugenio Fernandi took a lot of flack for not being mature enough for the role for Calaf, but, even while lacking the ultimate in confident mastery, he sounds suitably potent and in any event his blandness is an effective foil to Callas's buttery, commanding voice, and perhaps (rather than Guiseppi di Stefano, her usual La Scala partner) he was chosen for that very reason to complement and cede to her. When Callas finally does appear, she easily seizes the spotlight – her "In questa reggia" grips us with the repressed emotion and heavy but carefully controlled vibrato of the grand style, and then turns to riveting declamation for the riddle scene. Indeed, the final duet, despite the inherent weakness of the score, gains considerable power from Fernandi's audible struggle to keep up with both the dominant personality and the sheer voice of Callas. At least judging from an original Angel LP set, the recording is somewhat blurred and thin, the instrumental ensemble sounds more like a pit band than a lush symphony orchestra, and the mix favors the voices, all evoking an appropriate atmosphere of the theatre. Conductor Tullio Serafin takes a more flexible, expressive approach than his predecessors and adds some wonderful touches – the Persian prince's single phrase that's cut off (along with his head) is strangulated and for once horrifyingly convincing. Elizabeth Schwartzkopf sings Liù with great expression and tenderness, as one would expect from an accomplished lieder singer. The Masks (Piero de Palma, Renato Ercolani and Mario Borriello) interact wonderfully, painting an especially moving portrait of bureaucrats stuck in a rut of supporting a regime in which they lost faith long ago. (The sole disappointment among the supporting cast is a whiny, bleating Altoum, Turandot's father, more a caricature of age than feeble and sad.) Rising tenor Eugenio Fernandi took a lot of flack for not being mature enough for the role for Calaf, but, even while lacking the ultimate in confident mastery, he sounds suitably potent and in any event his blandness is an effective foil to Callas's buttery, commanding voice, and perhaps (rather than Guiseppi di Stefano, her usual La Scala partner) he was chosen for that very reason to complement and cede to her. When Callas finally does appear, she easily seizes the spotlight – her "In questa reggia" grips us with the repressed emotion and heavy but carefully controlled vibrato of the grand style, and then turns to riveting declamation for the riddle scene. Indeed, the final duet, despite the inherent weakness of the score, gains considerable power from Fernandi's audible struggle to keep up with both the dominant personality and the sheer voice of Callas.

Turandots of the 1960s were dominated by two wonderful recordings starring Birgit Nilsson, the emerging preeminent Wagnerian soprano of her time, with the Rome Opera Chorus and Orchestra.   A 1960 RCA set conducted by Erich Leinsdorf may leave a more satisfying artistic impression with greater psychological depth, while a 1965 EMI set led by Francesco Molinari-Pradelli is altogether more intense and viscerally exciting. The Liùs – Renata Tebaldi and Renata Scotto – and Timurs – Giorgio Tozzi and Bonaldo Giaiotti – are comparable, but the real differences stem from the Calafs. RCA's is Jussi Bjoerling, one of the world's most acclaimed lyric tenors, who brings to the role a sweet, expressive sensitivity and allows himself to be dominated by his fellow Swede's clarion authority. Corelli, though, is a high-octane shouter, whose legendary clashes, both artistic and personal, with Nilsson at the Metropolitan Opera fuelled an overtly dramatic rivalry on disc. Bjoerling wins Turandot through persuasion and understanding while Corelli prevails through sheer inflexibility and power. Perhaps the most telling moment comes at the climax of "In questa reggia" when the Prince and Turandot alternate and then sing together the ringing climactic phrase – Bjoerling lets Nilsson overwhelm his voice, as indeed the story requires, since at that point he is only an aspiring victim of her whims, while Corelli all but drowns her out, making it clear that nothing can stand in the way of an assured victory. Indeed, the pairing of the leads seems to guide the entire productions – the EMI is not only faster, but the voices are more forward in the mix, the conducting tends to be more impulsive, the detail less nuanced, the dynamics more compressed (and consistently louder). Both are fine, satisfying productions, with preference depending upon one's view of the basic dramatic premise. A 1960 RCA set conducted by Erich Leinsdorf may leave a more satisfying artistic impression with greater psychological depth, while a 1965 EMI set led by Francesco Molinari-Pradelli is altogether more intense and viscerally exciting. The Liùs – Renata Tebaldi and Renata Scotto – and Timurs – Giorgio Tozzi and Bonaldo Giaiotti – are comparable, but the real differences stem from the Calafs. RCA's is Jussi Bjoerling, one of the world's most acclaimed lyric tenors, who brings to the role a sweet, expressive sensitivity and allows himself to be dominated by his fellow Swede's clarion authority. Corelli, though, is a high-octane shouter, whose legendary clashes, both artistic and personal, with Nilsson at the Metropolitan Opera fuelled an overtly dramatic rivalry on disc. Bjoerling wins Turandot through persuasion and understanding while Corelli prevails through sheer inflexibility and power. Perhaps the most telling moment comes at the climax of "In questa reggia" when the Prince and Turandot alternate and then sing together the ringing climactic phrase – Bjoerling lets Nilsson overwhelm his voice, as indeed the story requires, since at that point he is only an aspiring victim of her whims, while Corelli all but drowns her out, making it clear that nothing can stand in the way of an assured victory. Indeed, the pairing of the leads seems to guide the entire productions – the EMI is not only faster, but the voices are more forward in the mix, the conducting tends to be more impulsive, the detail less nuanced, the dynamics more compressed (and consistently louder). Both are fine, satisfying productions, with preference depending upon one's view of the basic dramatic premise.

Speaking of Nilsson and Corelli, true opera buffs prize the many "unauthorized" Turandots that document memorable live performances. The potent Nilsson/Corelli dynamic is preserved on at least two occasions, both stunning.  On a 1964 La Scala set (on Opera d'Oro CDs) Gianandrea Gavazzeni conducts with a few quirky tempos but lots of dramatic leeway (the riddle scene is unbearably suspenseful) and Galina Viscnjevskaja pours her heart into Liù – her mesmerizing Act I "Signore, ascolta" is rewarded with a frenzied 45-second shouting ovation of the type normally heard only in sports arenas. The second comes from the New York Metropolitan Opera on March 4, 1961 (on numerous CDs and YouTube; a Pristine download has restored sound) when Leopold Stokowski, on crutches and substituting for Mitropoulos, made his conducting debut there at age 78 and made the most of it. More erratic than dramatic, he revels in the colorful atmosphere (especially the mysterious opening of Act III) and brings each act to an electrifying close, but couldn't resist tampering with the score, adding cymbals to the initial chords and lightening the orchestration of Turandot's aria. (Anna Moffo as Liù gets "only" a 30-second ovation.) In both live recordings the two leads are utterly electrifying, although they tend to stand out more in the La Scala set. Corelli easily cuts through the output of the full orchestra and chorus with startling ease (except at the end of the Met Act I, where the balances are badly skewed), yet his "Nessun dormas" shimmer with breathtaking, exquisite repose. Nilsson combines sheer icy power with loads of personality – she propounds her three enigmas with blood-curdling contempt, brilliantly offset by Corelli's unbridled triumph as he screams her name as his last answer. Alas, the contrived ending is beyond even their power to convey convincingly. But if I had to choose one recording to convince non-believers of the sheer human potency of Puccini's masterpiece, it would be either of these. On a 1964 La Scala set (on Opera d'Oro CDs) Gianandrea Gavazzeni conducts with a few quirky tempos but lots of dramatic leeway (the riddle scene is unbearably suspenseful) and Galina Viscnjevskaja pours her heart into Liù – her mesmerizing Act I "Signore, ascolta" is rewarded with a frenzied 45-second shouting ovation of the type normally heard only in sports arenas. The second comes from the New York Metropolitan Opera on March 4, 1961 (on numerous CDs and YouTube; a Pristine download has restored sound) when Leopold Stokowski, on crutches and substituting for Mitropoulos, made his conducting debut there at age 78 and made the most of it. More erratic than dramatic, he revels in the colorful atmosphere (especially the mysterious opening of Act III) and brings each act to an electrifying close, but couldn't resist tampering with the score, adding cymbals to the initial chords and lightening the orchestration of Turandot's aria. (Anna Moffo as Liù gets "only" a 30-second ovation.) In both live recordings the two leads are utterly electrifying, although they tend to stand out more in the La Scala set. Corelli easily cuts through the output of the full orchestra and chorus with startling ease (except at the end of the Met Act I, where the balances are badly skewed), yet his "Nessun dormas" shimmer with breathtaking, exquisite repose. Nilsson combines sheer icy power with loads of personality – she propounds her three enigmas with blood-curdling contempt, brilliantly offset by Corelli's unbridled triumph as he screams her name as his last answer. Alas, the contrived ending is beyond even their power to convey convincingly. But if I had to choose one recording to convince non-believers of the sheer human potency of Puccini's masterpiece, it would be either of these.

Perhaps the most universally acclaimed Turandot is the 1973 Decca set that boasts a fantasy–league dream cast that no opera house could ever afford.  In the title role, Joan Sutherland shapes her opening "In questa reggia" with nuance and precision that paints an intensely human and truly heart-rending portrait that evokes Puccini's own view of the princess as suffering – "suffocating under the ashes of her great pride." Luciano Pavarotti as Calaf lures her with the sheer beauty of his voice, fairly begging her to discover his name after turning the riddle scene into a battle not of wills but of wits. Montserrat Caballé provides a secure but simple portrait of Liù. Nicolai Ghiaurov invests Timor (the Prince's father) with a solid moral anchor. The long Ping/Pang/Pong scene that opens Act II (cast with Tom Krause, Pier Francesco Poli and Piero de Palma) sparkles with strikingly differentiated moods. Even the thankless role of the shriveled Emperor Altoum is enlivened by Peter Pears – still a resigned old man, yet hoping for a small measure of fulfillment in what remains of his life. For sheer beauty of vocal sound alone, the set is hard to beat. In the title role, Joan Sutherland shapes her opening "In questa reggia" with nuance and precision that paints an intensely human and truly heart-rending portrait that evokes Puccini's own view of the princess as suffering – "suffocating under the ashes of her great pride." Luciano Pavarotti as Calaf lures her with the sheer beauty of his voice, fairly begging her to discover his name after turning the riddle scene into a battle not of wills but of wits. Montserrat Caballé provides a secure but simple portrait of Liù. Nicolai Ghiaurov invests Timor (the Prince's father) with a solid moral anchor. The long Ping/Pang/Pong scene that opens Act II (cast with Tom Krause, Pier Francesco Poli and Piero de Palma) sparkles with strikingly differentiated moods. Even the thankless role of the shriveled Emperor Altoum is enlivened by Peter Pears – still a resigned old man, yet hoping for a small measure of fulfillment in what remains of his life. For sheer beauty of vocal sound alone, the set is hard to beat.  Zubin Mehta guides the London Philharmonic in a marvelously empathetic accompaniment and the superb recording conveys the sheer heft of the scoring while revealing all the subtleties with which it abounds, from the extraordinary blend of timbres in the opening brass chords to the normally inaudible harps in the finale. A convincing stereo soundstage enables even the massed ensembles to emerge with all components in place. Overall, it's a superb production. Zubin Mehta guides the London Philharmonic in a marvelously empathetic accompaniment and the superb recording conveys the sheer heft of the scoring while revealing all the subtleties with which it abounds, from the extraordinary blend of timbres in the opening brass chords to the normally inaudible harps in the finale. A convincing stereo soundstage enables even the massed ensembles to emerge with all components in place. Overall, it's a superb production.

One more Turandot, if only a curiosity for people (like me) who tend to enjoy an opera's music more than its literary or theatrical elements – a 1957 Kapp LP, Opera Without Words, featuring the Rome Symphony Orchestra conducted by Domenico Savino (who also may have prepared the adaptation). The first side squeezes Act I into 22 minutes (about 2/3 of the original), while the second condenses the rest to 24, presenting nearly the entire opening of Act II, just one enigma and answer from the riddle scene, "Nessun dorma," Liù's aria and cortege, a brief fanfare and the final "Nessun dorma" chorale reprise (thus bypassing nearly all of Alfano's work). Most of the vocal lines are presented with instruments (strings for the Act I choruses, celli for "Nessun dorma," a plaintive oboe for Liù's aria), but not in the Masks' scene, enabling us to focus on and appreciate the wonderfully inventive orchestration. Indeed, the instrumental distillation intensifies the splendor of the music and makes some structural sense to those who know the opera and can infer the dramatic action, but otherwise the transitions seem too abrupt and the progression illogical and meandering. Ironically, it serves to emphasize the close integration of elements in Turandot – and to recall how Puccini found himself at a total loss for music of the concluding scene without suitable text.

I found many sources useful to assemble the background for this article and to stimulate my own thoughts, and I recommend them for further reading. The most specialized is Williams Ashworth and Harold Powers' Puccini and Turandot – The End of a Great Tradition (Princeton University Press, 1991), which approaches the opera from many perspectives. I found many sources useful to assemble the background for this article and to stimulate my own thoughts, and I recommend them for further reading. The most specialized is Williams Ashworth and Harold Powers' Puccini and Turandot – The End of a Great Tradition (Princeton University Press, 1991), which approaches the opera from many perspectives.  Mosco Carner's Puccini – A Critical Biography (Knopf, 1959) comprises separate well-researched and beautifully written sections devoted to "The Man," "The Artist" (an extraordinary overview of themes and techniques across his career) and "The Work." Michele Girardi's Puccini – An International Art (University of Chicago Press, 2000) and Mary Jane Phillips' Puccini – A Biography (Northeastern University Press, 2002) are more current, although the latter has little to say about the music. Spike Hughes' Famous Puccini Operas (Robert Hale Ltd., 1957) is highly opinionated but presents a fascinating analysis of the opera. In a similar vein, William Berger's colloquial Puccini Without Excuses (Vintage, 2005) extends biography and analysis with surveys of pop cultural adaptations, famous Puccini singers, notable performances and even a glossary. The Puccini Companion (ed: William Weaver) has insightful articles by Jörgen Maehder and David Hamilton. Also valuable were the notes by George R. Marek and William Weaver to the LP sets led by Leinsdorf (RCA LSD-6149) and Molinari-Pradelli (Angel 3571 C/L). And for something completely different – a radical feminist take that's apparent from its title – there's Catherine Clement's Opera or the Undoing of Women (University of Wisconsin Press, 1988). Feel free to read these first – unless, of course, you're afraid to spoil the ending! Mosco Carner's Puccini – A Critical Biography (Knopf, 1959) comprises separate well-researched and beautifully written sections devoted to "The Man," "The Artist" (an extraordinary overview of themes and techniques across his career) and "The Work." Michele Girardi's Puccini – An International Art (University of Chicago Press, 2000) and Mary Jane Phillips' Puccini – A Biography (Northeastern University Press, 2002) are more current, although the latter has little to say about the music. Spike Hughes' Famous Puccini Operas (Robert Hale Ltd., 1957) is highly opinionated but presents a fascinating analysis of the opera. In a similar vein, William Berger's colloquial Puccini Without Excuses (Vintage, 2005) extends biography and analysis with surveys of pop cultural adaptations, famous Puccini singers, notable performances and even a glossary. The Puccini Companion (ed: William Weaver) has insightful articles by Jörgen Maehder and David Hamilton. Also valuable were the notes by George R. Marek and William Weaver to the LP sets led by Leinsdorf (RCA LSD-6149) and Molinari-Pradelli (Angel 3571 C/L). And for something completely different – a radical feminist take that's apparent from its title – there's Catherine Clement's Opera or the Undoing of Women (University of Wisconsin Press, 1988). Feel free to read these first – unless, of course, you're afraid to spoil the ending!

Copyright 2014 by Peter Gutmann

|