|

In one of the many bitter ironies of music history, Johann Sebastian Bach's six Brandenburg Concertos are now his most popular work and an ideal entrée to his vital  and variegated art, especially for those who mistakenly dismiss his 300-year old music as boring and irrelevant, yet Bach himself may never have heard them – nor did anyone else for over a century after his death. and variegated art, especially for those who mistakenly dismiss his 300-year old music as boring and irrelevant, yet Bach himself may never have heard them – nor did anyone else for over a century after his death.

Scholars must speculate to fill the many lapses in our knowledge of so much of Bach's music. Nearly half his output is deemed lost and many of his concertos exist only in later arrangements or spurious copies. But his so-called Brandenburg Concertos survive in his original manuscript, which he had sent to the Margrave of Brandenburg in late March 1721. Bach's own title was Six Concerts Avec plusieurs Instruments ("Six Concertos With several Instruments"); the familiar label adhered after first being applied by Philipp Spitta in an 1880 biography. Bach left a brief but telling account of their origin in his dedication to the presentation copy of the score, handwritten in awkward, obsequious French (which I've tried to reflect in translation): Scholars must speculate to fill the many lapses in our knowledge of so much of Bach's music. Nearly half his output is deemed lost and many of his concertos exist only in later arrangements or spurious copies. But his so-called Brandenburg Concertos survive in his original manuscript, which he had sent to the Margrave of Brandenburg in late March 1721. Bach's own title was Six Concerts Avec plusieurs Instruments ("Six Concertos With several Instruments"); the familiar label adhered after first being applied by Philipp Spitta in an 1880 biography. Bach left a brief but telling account of their origin in his dedication to the presentation copy of the score, handwritten in awkward, obsequious French (which I've tried to reflect in translation):

| Comme j'eus il y a une couple d'années, le bonheur de me faire entendre a Votre Altesse Royalle, en vertu de ses orders, & que je remarquai alors, qu'Elle prennoit qeulque plaisir aux petits talents que le Ciel m' a donnés pour la Musique, & qu' en prennant Conge de Votre Altesse Royalle, Elle voulut bien me faire l'honneur de me commander de Lui envoyer quelques pieces de ma Composition: j'ai donc selon ses tres gracious orders, pris la liberté de render mes tres-humbles devoirs à Votre Altesse Royalle, par les presents Concerts, que j'ai accommodés à plusieurs Instruments; La priant tres-humblement de ne vouloir pas juger leur imperfection, à la rigeur de gout fin et delicat, que tout le monde sçait qu'Elle a pour les piéces musicales … |

Since I had a few years ago, the good luck of being heard by Your Royal Highness, by virtue of his command, & that I observed then, that He took some pleasure in the small talents that Heaven gave me for Music, & that in taking leave of Your Royal Highness, He wished to make me the honor of ordering to send Him some pieces of my Composition: I therefore according to his very gracious orders, took the liberty of giving my very-humble respects to Your Royal Highness, by the present Concertos, which I have arranged for several Instruments; praying Him very-humbly to not want to judge their imperfection, according to the severity of fine and delicate taste, that everyone knows that He has for musical pieces … |

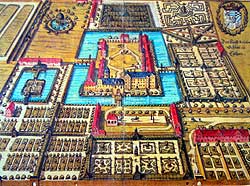

The Castle and Park of Cöthen

1650 engraving by Matthias Merven |

Scholars understand Bach to refer either to a trip he made to Berlin in March 1719 to approve and bring home a fabulous new harpsichord for his employer, Prince Christian Leopold of Cöthen, or possibly to an excursion they made the following year to the Carlsbad spa. Apparently, Bach played for the Margrave, who requested a score to add to his extensive music library. A persistent question, though, is why Bach took so long to respond, and then finally did.

Bach seemed happy at Cöthen. His patron not only loved music but was a proficient musician and spent a substantial portion of his income to maintain a private band of 18 and to engage traveling artists. As a Calvinist, Leopold used no music in religious observances, and freed Bach's energies for secular instrumental work and performances. Yet, the relationship may have begun to sour, as Bach applied for an organ post in Hamburg in late 1720 but was rejected. Bach's dedication continues:

| Je supplie tres humblement Votre Altesse Royalle, d'avoir la bonté de continuer des bonnes graces envers moi, et d'être persuadèe que je n'ai rien tant à coeur, que de pouvoir être employé en des occasions plus dignes d'Elle et de son service … |

I very humbly beg Your Royal Highness, to have the goodness to maintain his kind favour toward me, and to be persuaded that I have nothing more at heart, than to be able to be employed in some opportunities more worthy of Him and of his service … |

In other words, Bach intended the Brandenburgs as his resumé for a new job. The attempt was unsuccessful. Indeed, it's unclear what, if anything, the Margrave did with the presentation score once he received it.

Common wisdom is that the Margrave never bothered to perform these fabulous works, and perhaps never even examined the score. The three-fold basis for this notion is that the manuscript, which passed through private hands into a library, is in such fine condition as to suggest that it never was used, that Bach never received an acknowledgement (much less any reward), and that the works were considered so worthless that they were sold for a pittance upon the Margrave's death.

The Margrave of Brandenburg |

Yet, Malcolm Boyd deflates these myths, pointing out that a performance would not have used the full score, but rather copies of the individual parts, that the mere absence of any record of a response could evidence nothing more than the typically sparse documentation of the time, and that the score wasn't sold, but rather assigned a nominal value solely to assure that the Margrave's estate was divided equitably among his heirs.

Yet, the fact remains that the estate inventory neither cataloged the Brandenburgs nor even mentioned Bach, but rather included the scores in a bulk lot of 177 concertos while individually listing presumably more important works by Valentini, Venturini and Brescianello. In his Baroque Concerto Arthur Hutchings explains that this is hardly peculiar – despite subsequent acclaim, during his lifetime Bach was valued far more as a performer than as a composer, and his instrumental music was promptly forgotten once he attained his next (and final) post at Leipzig, where he focused again on religious music (although he did perform some concertos and orchestral Suites in the 1730s with the Collegium musicum, a fellowship of local amateurs and students).

Bach, around 1720 |

Joshua Rifkin offers a sadder but more practical explanation: "As would happen so often in his life, Bach's genius shot so far above the capabilities of ordinary musicians that his greatness was veiled in silence." Indeed, the Brandenburgs remained unknown for a half-dozen generations until they were finally published in 1850 in commemoration of the centenary of Bach's death and then were more widely circulated in 1869 as part of an authoritative Bach Gesellschaft edition. Even so, their popularity would have to wait nearly another century for the phonograph.

Since then, the Brandenburgs have been widely praised. On the most basic level, Christopher Hogwood claims that, beyond wanting to impress the Margrave with his versatility, Bach used them to codify and organize his miscellaneous output and so they represent an endeavor to imitate the wealth of nature with all the means at his disposal. Similarly, Abraham Veinus regards them as the exemplification of Bach's creative thinking, comprising the full range of his thought, variety of instrumentation and inner structure –  not a mere summary of the styles, forms and techniques of his predecessors but a realization and expansion of their full possibilities. Others view the Brandenburgs as an inextricable facet of Bach's overall religious bent. Thus, Karl Richter stresses that Bach's universality can only be understood in terms of the theological, mystical and philosophical foundations that infused all of his art, not a mere summary of the styles, forms and techniques of his predecessors but a realization and expansion of their full possibilities. Others view the Brandenburgs as an inextricable facet of Bach's overall religious bent. Thus, Karl Richter stresses that Bach's universality can only be understood in terms of the theological, mystical and philosophical foundations that infused all of his art, and Fred Hamel asserts that Bach was able to develop all the resources of his craft only after years of work in the devotional sphere and that Bach never distinguished religious and secular music, as his entire body of work was aimed for the glory of God. From that perspective, Bach's magnificent interplay of diverse musical elements can be seen as a reflection of his pervasive belief in the Divine harmony of the universe. Thus, Wilhelm Furtwängler sees Bach's music as symbolizing divinity by exuding supreme serenity, assurance, self-sufficiency and inner tranquility that transcends any personal qualities to achieve a perfect balance of its individual melodic, rhythmic and harmonic elements. Albert Schweitzer, too, views the Brandenburgs in metaphysical terms, unfolding with an incomprehensible artistic inevitability in which the development of ideas transverses the whole of existence and displays the fundamental mystery of all things. Yet, despite the philosophical depth of such analyses and the extraordinary density and logic of Bach's conception that leads academics to fruitfully dissect his scores, commentators constantly remind us that the Brandenburgs were not intended to dazzle theorists or challenge intellectuals, but rather for sheer enjoyment by musicians and listeners. and Fred Hamel asserts that Bach was able to develop all the resources of his craft only after years of work in the devotional sphere and that Bach never distinguished religious and secular music, as his entire body of work was aimed for the glory of God. From that perspective, Bach's magnificent interplay of diverse musical elements can be seen as a reflection of his pervasive belief in the Divine harmony of the universe. Thus, Wilhelm Furtwängler sees Bach's music as symbolizing divinity by exuding supreme serenity, assurance, self-sufficiency and inner tranquility that transcends any personal qualities to achieve a perfect balance of its individual melodic, rhythmic and harmonic elements. Albert Schweitzer, too, views the Brandenburgs in metaphysical terms, unfolding with an incomprehensible artistic inevitability in which the development of ideas transverses the whole of existence and displays the fundamental mystery of all things. Yet, despite the philosophical depth of such analyses and the extraordinary density and logic of Bach's conception that leads academics to fruitfully dissect his scores, commentators constantly remind us that the Brandenburgs were not intended to dazzle theorists or challenge intellectuals, but rather for sheer enjoyment by musicians and listeners.

In his introduction to the Eulenburg edition of the scores, Arnold Schering notes that the concerto was not only the most popular form of instrumental music in the late Baroque era, but also the primary vehicle of expression for grand, sublime feeling, a role later to be assumed by the symphony. In his introduction to the Eulenburg edition of the scores, Arnold Schering notes that the concerto was not only the most popular form of instrumental music in the late Baroque era, but also the primary vehicle of expression for grand, sublime feeling, a role later to be assumed by the symphony.

Boyd notes that with the exception of the First, each Brandenburg follows the convention of a concerto grosso, in which two or more solo instruments are contrasted with a full ensemble, and where a slow movement in the relative minor is bracketed by two fast movements, mostly structured as a ritornello (Italian for "return") in which the opening tutti (played by the full ensemble) reappears as a formal marker between episodes of display by the concertino (solo instruments) and again as a conclusion, thus producing a psychologically satisfying structure. (After all, it's only human nature to seek the comfort of returning to and dwelling in the familiar.) Wilhelm Fischer further divides a traditional ritornello into a motivic opening that establishes the key and character of the work, a continuation of sequential repetition, and a cadential epilog. (Italian for "return") in which the opening tutti (played by the full ensemble) reappears as a formal marker between episodes of display by the concertino (solo instruments) and again as a conclusion, thus producing a psychologically satisfying structure. (After all, it's only human nature to seek the comfort of returning to and dwelling in the familiar.) Wilhelm Fischer further divides a traditional ritornello into a motivic opening that establishes the key and character of the work, a continuation of sequential repetition, and a cadential epilog.

Vivaldi and others who established the concerto grosso model used nuances of texture, tone coloration and novel figurations to contrast the ensemble's ritornello and the solo episodes. Bach, though, tends to fluently blend and integrate them. Indeed, in his treatise on orchestration, Adam Carse notes that Bach conceived his parts generically rather than in terms of specific instruments, and distributed them impartially and largely interchangeably, such that all sink into a common contrapuntal net without consideration of balance in the modern sense of orchestration. Even so, some scholars assume that Bach customized the Brandenburgs according to the forces the Margrave had available (after all, why would he present a lavish gift that the Margrave couldn't use?).  Hans Günter-Klein, though, correlated Prince Leopold's account books with the instrumentation of the Brandenburgs and asserted that the scores reflect the salaried musicians available at Cöthen, and therefore preserve a document of the musical practices there. He concluded that the Brandenburgs were written for performance there. Indeed, Rifkin claims that the Margrave had a small orchestra that lacked both the instruments and sufficiently skilled players to cope with the demands of the Brandenburgs' diverse and difficult parts. Hans Günter-Klein, though, correlated Prince Leopold's account books with the instrumentation of the Brandenburgs and asserted that the scores reflect the salaried musicians available at Cöthen, and therefore preserve a document of the musical practices there. He concluded that the Brandenburgs were written for performance there. Indeed, Rifkin claims that the Margrave had a small orchestra that lacked both the instruments and sufficiently skilled players to cope with the demands of the Brandenburgs' diverse and difficult parts.

Thurston Dart calls Bach's presentation copy of the Brandenburgs a masterpiece of calligraphy but of far less value as a musical source due to the many errors that suggested haste. Fortunately, secondary sources exist to remedy such lapses, notably copies made in 1760 by Frederich Penzel of earlier versions (now all lost). It is generally assumed that all the Brandenburgs were selected from a large body of Bach's existing concertos, some of which we know from admirers' copies and Bach's own later arrangements for other instruments, although none of the originals survives.

While Veinus traces the individual concertos to models by Telemann, Fasch, Molter, Gaupner, Heinichen and others, Hutchings notes that the Brandenburgs did not simply sum up his predecessors' work, as he did with chorales and fugues, but rather comprise an extraordinary exploration of different relationships of solo and tutti. Since the Brandenburg Concertos were never meant to be played as a continuous set (which would have sidelined most of the players and exhausted the listeners), their order is of little import, although there was a certain logic for Bach's presentation copy to have led off with the most elaborate and to have ended each half of the set with the comfort of strings. Yet it seems apt to consider them in the approximate order of their composition.

in B-flat major for 2 violas de braccio, 2 violas da gamba, violincello + continuo (violone and cembalo) in B-flat major for 2 violas de braccio, 2 violas da gamba, violincello + continuo (violone and cembalo)

The last of the Brandenburg Concertos is often considered the oldest, as its instrumentation conjures a 17th century English consort of viols, similar scoring had been used by Bach in his earlier Weimar cantatas, and its structure relies heavily upon both the ancient canon form and the conservative Baroque gesture of a chugging bass of persistent quarter-notes.

A viola da gamba |

Yet, typically, Bach combines a knowing salute to the past with a bold leap into the future, raising the violas, customarily embedded in the continuo accompaniment, to solo status. The unprecedented gesture was triply suitable – the viola was Bach's own favorite orchestral instrument (as he once put it, placing him "in the middle of the harmony"), it was also the instrument played by his patron Prince Leopold, and the Margrave's orchestra was known to have employed two especially accomplished violists.

Scholars assume that Bach only had enough forces at Cöthen for one player per part. Indeed, performances with full string sections, or even large chamber ensembles, no matter how well rehearsed, tend to blur the precisely articulated interplay of buoyant rhythms and swamp the harpsichord, whose bright plucked overtones need to emerge from the depth of the strings. Moreover, the nasal sound of violas da gamba (six-string bass viols held between the legs) and a single violone are needed for bright, transparent middle and bass lines that complement rather than thicken the tone of the featured violas de braccio (hand-held violas comparable to current ones) and solo cello. Similarly, modern substitutions of deeper and more powerful modern instruments, including a double bass, unduly deepen the sonority and fuse the timbres.

In one sense, the work seems a concerto for two violas to display Bach's love of his instrument and its full range of expressive possibilities. Yet, it is their interplay, both with each other and with the cello and continuo, that characterizes each of the three movements, thus exemplifying the claim of Johann Nicolaus Forkel, Bach's first biographer, that Bach considered the essence of a polyphonic composition to be a symbolic tonal discussion among instruments, each presenting arguments and counterpoints, variously talking and lapsing into silence to listen to the others.

Shorn of the violins' customary brilliance, the dark timbre suggests a harbinger of the mystery and somber thoughts of the Romantic era to come. Indeed, Boyd sees the instrumentation as an allegory of progress, as Bach elevates the then-newest member of the string family to prominent status while relegating the older viols to the background. Yet Bach ingeniously creates a compelling and complex aural image of irresistible gaiety that arises out of and is enriched by its seemingly melancholy components.

The sections of the first movement are closely integrated into a continuous flow of vigorous thrust, led by the two violas in tight canon a mere eighth-note apart during each of the six ritornellos, blending into a lively dialogue with the gambas during the five episodes, all over a persistent quarter-note continuo rhythm. The second is a lovely, if somewhat quaint, meditation for violas and cello. The finale is an irresistibly propulsive dance in 12/8 time with astoundingly catchy primary and counter-melodies, in which Bach seems to tease us as the violas constantly begin, abandon and resume canonic imitation. Indeed, while Bach is reputed to lack humor, he manages to play an unintended joke on those of us relegated to listening on record – the violas constantly switch parts but the difference is inaudible and thus impreceptible without the visual clues in a concert. Perhaps out of respect for the limited stamina of his royal soloist, after sitting out the adagio, the gamba parts of the finale are easy accompaniment, leaving all the work to the violas and occasional fits of activity from the cello.

in G major for 3 violins, 3 violas and 3 celli + continuo (violone and cembalo) in G major for 3 violins, 3 violas and 3 celli + continuo (violone and cembalo)

Here, too, Bach explores string sonority, but with a richer palette than in the Sixth. There are no solo instruments as such, and Veinus considers the work more symphonic than a true concerto. Yet Hutchings calls the Third the greatest stroke of originality in any concerto grosso, due to Bach's handling of the same players in constantly evolving groupings and solo flights to imply concertino and tutti by spreading, opposing, unifying, concentrating and balancing their registers.

Rifkin aptly describes the first movement as a framework of homogenous sonority which Bach varies through perpetual juxtaposition of different sudivisions of the ensemble. The inventiveness of this approach emerges by comparing the first movement of the Brandenburg version with Bach's rescoring of it as the opening of a 1729 cantata augmented with horns, oboes, tailles (tenor oboes) and a bassoon. The strings still dominate but the added instruments emphasize cadences, add inner voices and underscore the harmony with long held chords, thus making explicit what the original implies with far greater impact. The third movement is in binary dance form, with its two complementary sections each repeated.

Between them lies a puzzle that has perplexed scholars and challenged performers. The second movement, labeled adagio, consists of two chords forming a bare Phrygian cadence of the type that often links a slow middle movement in the relative minor to a vivid major-key finale, but with an intriguing sense of open expectancy. Here, the chords occur in the middle of a page, so clearly no music was lost. Yet the remainder of the score is fully detailed and presumably was intended as complete guidance to the Margrave's forces, as Bach had no realistic expectation of preparing a performance. What to do?

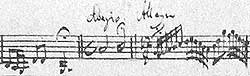

Violin staff of the Third Concerto autograph

– the two-note adagio |

Several scholars note that Corelli and other contemporaries inserted similar bare cadences in their scores, and Reiner, Casals, Klemperer and others schooled in Romantic interpretation play it unadorned in their recordings. Yet when played literally it sounds far too short to serve as a needed respite between two rollicking neighboring movements. Other scholars assume that it must have been a conventional shorthand instruction that all performers of the time would have understood to require embellishment or an improvised interlude (even though the meaning has since been lost). Yet the question remains as to which instruments would do this. In several recordings (Cortot, Goberman, Horenstein, Ristenpart, Karajan, I Musici) the harpsichordist ornaments the first or both chords with arpeggiated runs. Others (Sacher, Richter, Paillard) go further, with the harpsichordist providing brief fantasies recalling thematic material from the preceding movement. Yet the soft tinkling of that instrument seems dwarfed by the sonority and at odds with the string texture of the surrounding movements. (Sacher's and Paillard's engineers avoid the former problem by cranking up the harpsichord volume for the passage to unnatural levels.) Busch, Harnoncourt, Hogwood and Britten avoid both issues by having their violinists embroider the chords.

Other recordings (Pommer and Pinnock) attempt to restore the usual formal balance of three entire movements by having their violinists extemporize at greater length. Still others extend the effect by inserting a slow movement from one of Bach's other, and often more obscure, works. Thus, Dart uses the adagio from a Sonata in G for violin and continuo, Munchinger the ruminative, delicate Concerto # 15 for solo harpsichord (itself possibly an arrangement of a Telemann piece), Koussevitzky the tragic sinfonia from the Cantata # 4, the Brandenburg Consort the adagio from Bach's Violin Sonata in G, and Menuhin an arrangement by Britten for violin, viola and continuo of the gracious, mournful lento of Bach's organ Trio Sonata # 6 (although curiously Britten omits all the embellishments found in the three-part organ score and didn't use this movement in his own recording). While none of these seems wholly satisfactory, they all present intriguing attempts to surmount the vexing snag posed by Bach.

in F major for 2 horns, 3 oboes, violino piccolo, first and second violins, violas + continuo (bassoon, cello, violone grosso and cembalo) in F major for 2 horns, 3 oboes, violino piccolo, first and second violins, violas + continuo (bassoon, cello, violone grosso and cembalo)

The only Brandenburg Concerto in four movements, the First may appear to be the conventional fast-slow-fast form to which a final dance section was added, but scholars trace a more complex origin, in which the first, second and fourth movements comprised a "sinfonia" to introduce a 1713 Hunting Cantata and thus was more like a standard suite of the time. Boyd goes further to speculate that to create the character of a concerto, Bach later added the present third movement with its prominent violin solo, the short phrasing of which suggests separate origin as a now-lost choral piece. (Bach later adapted the third movement back to a choral setting to open a 1726 cantata.)

The overall orchestration is unusual. The sheer number of instruments gives the work more of an orchestral than chamber character. Karl Geiringer calls it a "concerto symphony." To expand the range of the sonority, Bach specifies in lieu of his standard violone a "violone grosso" played an octave below the bass staff (corresponding to the modern double bass) and in lieu of a solo violin a "violono piccolo," an obsolete small violin with scordaturo tuning a major third above notation and whose lighter bow, less resonant body and tighter string tension yield a sweeter, lighter tone. Harnoncourt asserts that the instrument was chosen purely for its tone color, rather than any technical reason. Indeed, Boyd notes that Bach didn't exploit its higher range and that its reduced volume is overwhelmed by the large ensemble. Bach himself used a regular violin in his earlier sinfonia version.

Perhaps Bach led with this work to give his offering a strong start for a lazy patron who might judge the set only by its opening. Yet, despite its immediate appeal to conservative ears, each movement has a remarkable feature typical of Bach's irrepressible sense of invention.

The first movement is four minutes of pure jaunty swaggering infectious elation, yet there's an subtext of discomfort. The two natural horns appear to be making their first solo appearance in a concerto.

A natural horn |

Yet, their raucous sound (more strident than our more mellow valved modern horns) disturbs the otherwise carefully-balanced texture and their insistent bellowing hunting calls disrupt the overall rhythm. Harnoncourt suggests symbolic significance in that the horn players were not part of the regular court orchestra. If so, their strident sound suggests an unwanted guest.

The second movement, slow and soft, is scored for the full ensemble (sans horns) rather than the usual reduced forces. The mournful melody is not only traded in canon between the oboe and violino piccolo but descends all the way down into the bass to augment its standard role as pure accompaniment. The early version (without the violono piccolo) balances the solo oboe against all the violins for an earthier tone, but Smith, for one, cites the complex ornamentation in the score as suited for a single performer. The melancholy mood is tinged with bitterness, as the harmony is flecked with dissonant minor seconds. The most astounding touch is saved for the very end as each note of a conventional descending bass is first supported by the oboes but then cancelled by unexpected chords in the strings, resulting in Boyd's citation of a "frozen harmony" with a remarkably dry 20th century sound.

The third movement is the closest approach to a standard concerto format, although the violino piccolo, amid its florid solos, is given many emphatic slashing triple-stopped figures, perhaps struggling to assert itself. As if to avoid fatigue, the insistent 6/8 rhythm is broken by a two-bar adagio at measure 82 (of 120) and then resumes to the rollicking end.

Although the concerto proper appears to conclude at that point, Bach adds a set of four dances in which all members of the ensemble are displayed – a minuet for the full band is heard four times, enfolding a trio for oboes and bassoon, a Polacca for strings (absent from the 1713 sinfonia version) and a second trio for horns and oboes. The overall structure, alternating the full minuet with the softer interludes, evokes the ritornello form, yet there are a few surprises here, too – in the first trio the bassoon emerges from its role buried in the continuo, the polka erupts into a jaunty triplet sprint and the second trio is in 2/4 time, although the shift is barely apparent as the horns and oboes preserve the overall rustic mood.

in F major for "tromba," flute, oboe, violin + ripieno (first and second violins, viola and violone) + continuo (cello, cembalo) in F major for "tromba," flute, oboe, violin + ripieno (first and second violins, viola and violone) + continuo (cello, cembalo)

Of the Brandenburgs, the Second is considered the closest to the standard concerto grosso model, although more in the sense of its sound than its structure. Hans-Joachim Schulz felt that it arose from Bach's love of experimentation and the challenge of writing for a solo contingent of four similarly pitched instruments differentiated by their dissimilar means of tone production. William Mann felt that Bach's intent was to explore their different sonic coloration. Yet, as many have pointed out, Bach rarely writes idiomatic, individualized parts that would exploit the unique capabilities of each instrument, but rather tends to write abstractly while respecting their limitations.

Thus, the first movement,

A Baroque oboe |

as analyzed by Boyd, is built not upon schematic alteration of orchestral and solo sections but rather upon a broad tonal structure with cadential landmarks. Yet, the coloration is intense – within the first minute alone we hear sections of violin solo, violin and oboe, oboe and flute, and flute and tromba, all separated by brief interjections of the string ripieno.

The instrumentation, though, does present a fundamental problem. Despite intensive research, scholars remain unsure what Bach meant when he designated one of the solo instruments a "tromba." While often taken to mean a trumpet in F played a major fourth above its score notation, others point out that Bach never wrote any other part for such an instrument, that F is the natural key for horns rather than trumpets, and that an authentic copy of the score and parts by Penzel specifies use of either a trumpet or a hunting horn. Nor can any hint be gleaned from the personnel available to Bach, as musicians routinely played several brass, wind or string instruments. Indeed, while a trumpet overwhelms the other soloists (especially the soft recorder), a horn (played a major fifth below the score) is better balanced.

While most recordings use a modern trumpet, others take a variety of approaches. Menuhin uses a softer piccolo trumpet, Harnoncourt a more mellow natural trumpet, Enesco and Casals a soprano saxophone, and Dart a hunting horn. All achieve a more natural balance among the solo instruments, especially the gentle breathy recorder. Harnoncourt considers this a prime illustration of the difference between the sounds Bach heard (and wrote for) and those of today, which can distort his intentions.

Yet, however it sounds, the tromba aptly resides on the top staff, as it enjoys a commanding position in the score. Its interjections provide shape and emphasis to the first movement, in which the soloists jostle for control by progressively appropriating the tutti theme. While the trumpet rests during the andante, a lovely contemplation in which the other soloists constantly evolve a short, simple theme over a walking bass, it launches the third movement with a fugue theme that it grudgingly shares with the others while reducing the orchestra to a purely subsidiary (and often silent) supporting role. The role of the tromba exemplifies Karl Geiringer's observation that Bach often likes to single out one of the concertino members as its leader and protagonist and makes its part more brilliant and technically exacting.

in G major for violin, 2 "flauti d'echo" + ripieno (first and second violins, viola, cello, violine and cembalo) in G major for violin, 2 "flauti d'echo" + ripieno (first and second violins, viola, cello, violine and cembalo)

The Fourth, too, presents a mystery of instrumentation for performance. No one knows what Bach meant when he specified "flauti d'echo" as two of the three solo instruments. Harnoncourt posits that the term merely refers to echo effects in the second movement where the flutes imitate violin figures and indeed most performances use standard flutes.

Baroque recorder |

In his introduction to the authoritative Eulenburg score, Roger Fiske notes that when Bach later transcribed the entire piece as a harpsichord concerto in Leipzig, he designated the parts as "flauti à bec" (recorders) and indeed their softer timbre melds well with the solo violin. (Ristenpart, Menuhin and Pearlman all opt for recorders in their recordings.) Dart, though, asserted that the intent was a flageolet, a type of shrill tin-whistle that was a popular novelty of the time used to teach birds to sing and which sounds an octave above the score, thereby keeping its line consistently above the violin and clarifying the texture. Smith, though, notes that there was no tradition of playing the flageolet professionally and opts for soprano recorders (also sounding an octave higher) which Marriner uses in his recording; either way, the result is piercing, shrill and somewhat tiring to hear through an entire piece.

The prominence of the violin in the outer movements, and the extreme difficulty of its part (more so than in Bach's three actual violin concertos), including delirious extended sequences of extremely rapid notes, has led some to consider the Fourth a violin concerto, although in the central andante it mostly plays with the ripieno violins to support the flutes. Indeed, Mann notes that the first movement looks forward to the structure of the classical and even romantic concerto, as the opening tutti is an unusually long 82 measures (well over a minute) and is not heard in its entirety again until the close, yielding to a central section of intensive development ordered by repetitions of the opening G-A-B three-note motif.

The lovely andante atypically employs the full ensemble, providing a richer foundation than the continuo that customarily accompanies the soloists in middle movements. But it's the finale that has attracted the most attention. Boyd hails it as a genuinely successful fusion, rather than a mere amalgam, of two radically different forms – the contrapuntal rigor of the fugue and the virtuoso display of the concerto, a combination of gravitas and high spirits that shifts the focus from the first to the last movement. Rifkin agrees and salutes it as the most complex movement in the Brandenburgs and a stunning monument to Bach's virtuosity, as the fugal exposition and episodes align with the concerto's tutti and solo runs even as the contrasts among instruments reflect distinctions between free and subject-derived thematic material. But technical classifications aside, the finale simply brims with invention and high spirits and is utterly thrilling to hear. Indeed, it creates so much rousing momentum that Bach slams on the breaks with sudden rests three times before the final surge in an effort to interrupt the flow and prepare for the finish.

in D major for flute, violin, cembalo + ripieno (violin, viola, cello and violone) in D major for flute, violin, cembalo + ripieno (violin, viola, cello and violone)

The fifth Brandenburg is thought to have been the last written, intended as a vehicle to show off the new Cöthen harpsichord. Bach presumably played the solo part himself; Philipp Spitta considered the part to have demanded finger dexterity that no one else possessed at the time. The Fifth is the most historically important of the Brandenburgs, as it is the earliest known instance in which the harpsichord is elevated out of the role of continuo accompaniment to solo status.

Baroque bassoon |

Harnoncourt praises it as employing "all the technical and tonal possibilities of this instrument in such a masterly fashion that this work becomes at the same time the beginning and climax of its category." Boyd, though, views it as a prophetic combination of thematic references and brilliant passagework in an improvisatory style that paved the way to Mozart's perfection of the genre. In any event, while the other Brandenburgs held little interest for the following generations, the Fifth is the only one to have circulated after Bach's death (in copies by others) as it spoke to their interest in the emerging solo keyboard concerto.

The unusually lengthy first movement literally breaks the mold of the old ritornello form, as the opening melody returns only in fragments and cedes to a long serene central section far more developed and of greater emotional contrast than a normal episode. Throughout, the harpsichord not only holds its own but keeps escaping its role as accompanist to override and grab the spotlight from the solo flute and violin. But most remarkable of all is the cadenza. As if to emphasize its import, the other instruments don't boldly lead up to the lengthy solo display as they would in later concertos, but rather slow down and drop off, as if respectfully bowing, turning away and receding before the royal presence of the majestic harpsichord. An earlier version of the cadenza (known only in posthumous copies by others) was 18 measures long and seems more suited to the scope of the surrounding movement. The final version is 65 measures (about 3 minutes, to which could be added the prior 16 bars in which the solo thoroughly dominates the texture) and runs an astounding gamut of frantically forceful and concentrated figurations in rapid 16th-, triplet 16th- and 32nd-notes, ending in a hugely suspenseful chromatic sequence that leads to the final orchestral statement of the principal melody which has gone unheard since the opening.

The reflective second movement (marked "affettuoso") displays a more subtle formal daring by suggesting the solo and tutti divisions of the outer movements through changes in intensity as the harpsichord overflows the bounds of accompaniment with rapid figures that thicken the texture and imply shifts in dynamics beyond those marked in the score. The canonic basis of the second movement emerges more fully in the fugal finale, in which the harpsichord not only is a full participant an gigue begun by the violin and flute, but soon dominates the entire ensemble with dense 16th-note passages and trilled held notes.

There had been recordings of individual Brandenburg Concertos (the earliest seem to have been by Goosens and the Royal Albert Hall Orchestra in 1923 and Höberg and the Berlin State Opera Orchestra in 1925, There had been recordings of individual Brandenburg Concertos (the earliest seem to have been by Goosens and the Royal Albert Hall Orchestra in 1923 and Höberg and the Berlin State Opera Orchestra in 1925, both, curiously, of the Third). Yet it was with an integral 1935 recording of all six that the Brandenburgs came into prominence. Adolph Busch was one of Germany's most prominent violinists and its busiest soloist and chamber musician. Although Aryan and thus not personally at risk, he was sickened over the rising tide of repression and emigrated, not quietly but with strident denunciations of the fascist regime, vowing to return only once all the Nazi leaders had been hanged. As expressed by André Tubeuf in a deeply moving tribute, Busch left everything material behind, even his prized Stradivarius violin, yet took with him into exile something far more precious. In Italy, England and finally America, along with his son-in-law Rudolf Serkin, he became a fervent missionary for the eternal truths of German culture and planted and nurtured the spirit of Bach throughout the free world. both, curiously, of the Third). Yet it was with an integral 1935 recording of all six that the Brandenburgs came into prominence. Adolph Busch was one of Germany's most prominent violinists and its busiest soloist and chamber musician. Although Aryan and thus not personally at risk, he was sickened over the rising tide of repression and emigrated, not quietly but with strident denunciations of the fascist regime, vowing to return only once all the Nazi leaders had been hanged. As expressed by André Tubeuf in a deeply moving tribute, Busch left everything material behind, even his prized Stradivarius violin, yet took with him into exile something far more precious. In Italy, England and finally America, along with his son-in-law Rudolf Serkin, he became a fervent missionary for the eternal truths of German culture and planted and nurtured the spirit of Bach throughout the free world.  As one of his first steps, he formed the Busch Chamber Players (comprised nearly half of women – an extreme rarity at the time – and including such famous soloists as Aubrey Brain on horn, Marcel and Louis Moyse on flutes and, of course, Busch on violin and Serkin onpiano). In October 1935 they recorded the complete Brandenburgs (as well as all four Suites for Orchestra). A hugely successful best-seller, this was one of the most important recordings ever made, as it brought Bach to the attention of a world that had been content to relegate him to the dry bins of history and academic theory. Infused with humanity and spirituality, yet purged of romantic sentimentality, the Busch readings present the music in all its integrity and genius. While using modern instruments and a piano rather than a harpsichord, the Busch Brandenburgs are no mere relics. They remain vastly gratifying in their own right as well as a timeless touchstone of selfless devotion to the essential soul of Bach's immortal art. As one of his first steps, he formed the Busch Chamber Players (comprised nearly half of women – an extreme rarity at the time – and including such famous soloists as Aubrey Brain on horn, Marcel and Louis Moyse on flutes and, of course, Busch on violin and Serkin onpiano). In October 1935 they recorded the complete Brandenburgs (as well as all four Suites for Orchestra). A hugely successful best-seller, this was one of the most important recordings ever made, as it brought Bach to the attention of a world that had been content to relegate him to the dry bins of history and academic theory. Infused with humanity and spirituality, yet purged of romantic sentimentality, the Busch readings present the music in all its integrity and genius. While using modern instruments and a piano rather than a harpsichord, the Busch Brandenburgs are no mere relics. They remain vastly gratifying in their own right as well as a timeless touchstone of selfless devotion to the essential soul of Bach's immortal art.

Despite its renown, the Busch series was not the first full set of Brandenburgs to be recorded by a single ensemble. That honor goes to Alfred Cortot and his Orchestre de l’École Normale de Musique, Paris, waxed in May (the Fifth) and June (the rest) 1932 (Koch or EMI CDs).  If the Busch set was a labor of affection and respect, then Cortot’s was one of heartfelt passion and adventure. His orchestra was a group of advanced students (possibly augmented by faculty) at a conservatory he had founded in 1919 and the grooves of his records fairly burst with their ardent sense of exploration. The cohesion tends to be quite coarse and the horn and trumpet playing wildly inaccurate, but the players’ raw enthusiasm, far removed from the polished “professional” presentations of the next three decades, heralds the unruly (and authentic) sounds recaptured in more recent, historically-informed outings, as do the overall tempos (ten minutes faster than Busch’s). Famed primarily as a deeply poetic, if technically insecure, pianist, Cortot also was a pioneering conductor, responsible for the French premieres of Wagner operas and many contemporary works. His Brandenburg readings are heavily romanticized, with emphatic pauses and slowdowns to signal cadences and other structural markers, bold dynamic swells to shape phrasing, minimal trills and other ornamentation, and occasional rescoring (notably string pizzicato). In his notes to the Koch edition, Teri Noel Towe attributes these "unforgiveable ... interpretive shenanigans" to a Wagnerian sense of a partnership of equals between a (then-) eclipsed composer in desperate need of modern presentation and a headstrong interpreter demanding to impose his own personality. Perhaps most remarkable is Cortot's Fifth, in which his colleague Jacques Thibaud gives such a strongly-underlined and assertive yet ineffably sweet reading of his part as to shift the perspective into a de facto violin concerto – at least until the cadenza, played by Cortot on the piano (rather than the harpsichord he used for all the other concertos) with deeply human feeling. While Cortot’s highly personal touches diverge further from our modern notions of authentic Baroque performance style than any other recording, the overall impression is one of constant vitality and discovery that still resonates through the many years. If the Busch set was a labor of affection and respect, then Cortot’s was one of heartfelt passion and adventure. His orchestra was a group of advanced students (possibly augmented by faculty) at a conservatory he had founded in 1919 and the grooves of his records fairly burst with their ardent sense of exploration. The cohesion tends to be quite coarse and the horn and trumpet playing wildly inaccurate, but the players’ raw enthusiasm, far removed from the polished “professional” presentations of the next three decades, heralds the unruly (and authentic) sounds recaptured in more recent, historically-informed outings, as do the overall tempos (ten minutes faster than Busch’s). Famed primarily as a deeply poetic, if technically insecure, pianist, Cortot also was a pioneering conductor, responsible for the French premieres of Wagner operas and many contemporary works. His Brandenburg readings are heavily romanticized, with emphatic pauses and slowdowns to signal cadences and other structural markers, bold dynamic swells to shape phrasing, minimal trills and other ornamentation, and occasional rescoring (notably string pizzicato). In his notes to the Koch edition, Teri Noel Towe attributes these "unforgiveable ... interpretive shenanigans" to a Wagnerian sense of a partnership of equals between a (then-) eclipsed composer in desperate need of modern presentation and a headstrong interpreter demanding to impose his own personality. Perhaps most remarkable is Cortot's Fifth, in which his colleague Jacques Thibaud gives such a strongly-underlined and assertive yet ineffably sweet reading of his part as to shift the perspective into a de facto violin concerto – at least until the cadenza, played by Cortot on the piano (rather than the harpsichord he used for all the other concertos) with deeply human feeling. While Cortot’s highly personal touches diverge further from our modern notions of authentic Baroque performance style than any other recording, the overall impression is one of constant vitality and discovery that still resonates through the many years.

Also of considerable interest is the post-World War II set by Serge Koussevitzky and the Boston Symphony Orchestra (Pearl CDs), performed not by a chamber-sized pickup group but by an established full symphonic orchestra. Taking advantage of the richer complement of musicians, the First and Third sound like they were played by far larger string sections than Busch or Cortot used, with solo parts doubled (or more), although the forces are pared back to customary size in the other concertos (and all the slow movements). The result of the more massive sonority is a blurring of textures and ornamentation, with keyboard continuo omitted altogether (except, of course, for the Fifth, featuring a wonderfully expressive piano solo by a young Lukas Foss). The pacing can push the boundaries of convention, as when the third movement of the First sprints only to contrast with an exceptionally relaxed minuet finale. Once set, though, tempos are held steadfast, reflecting both Koussevitzky’s view of music as a disciplined rite (an approach fully compatible with Bach’s religious inspiration) and Christopher Howell’s cogent observation that the old style of Bach playing featured an unforced swinging motion that over a long span gives a sense of timeless inevitability. Indeed, there’s a pervasive sense of natural, artless momentum here, even without particular touches (although the calm middle movements are especially earnest, with the Sixth downright ravishing). The only curious feature is Koussevitzky’s use of the brief but mournful sinfonia from Bach’s Cantata # 4 (Christ lag in Todesbanden) ("Christ lay by death enshrouded") for the adagio interlude of the Third, which seems a bit out of character as it brings the bouncy work to an utter halt rather than a thoughtful pause. Koussevitzky's reading of Bach is of the “old school” – straightforward, persistent and smooth – yet modern, as he avoids romantic clichés with minimal vibrato, steady pacing and constant dynamics. In a sense, he melds Busch’s fundamentally respectful discretion with tantalizing hints of Cortot’s tangible spirit of outgoing commitment. performed not by a chamber-sized pickup group but by an established full symphonic orchestra. Taking advantage of the richer complement of musicians, the First and Third sound like they were played by far larger string sections than Busch or Cortot used, with solo parts doubled (or more), although the forces are pared back to customary size in the other concertos (and all the slow movements). The result of the more massive sonority is a blurring of textures and ornamentation, with keyboard continuo omitted altogether (except, of course, for the Fifth, featuring a wonderfully expressive piano solo by a young Lukas Foss). The pacing can push the boundaries of convention, as when the third movement of the First sprints only to contrast with an exceptionally relaxed minuet finale. Once set, though, tempos are held steadfast, reflecting both Koussevitzky’s view of music as a disciplined rite (an approach fully compatible with Bach’s religious inspiration) and Christopher Howell’s cogent observation that the old style of Bach playing featured an unforced swinging motion that over a long span gives a sense of timeless inevitability. Indeed, there’s a pervasive sense of natural, artless momentum here, even without particular touches (although the calm middle movements are especially earnest, with the Sixth downright ravishing). The only curious feature is Koussevitzky’s use of the brief but mournful sinfonia from Bach’s Cantata # 4 (Christ lag in Todesbanden) ("Christ lay by death enshrouded") for the adagio interlude of the Third, which seems a bit out of character as it brings the bouncy work to an utter halt rather than a thoughtful pause. Koussevitzky's reading of Bach is of the “old school” – straightforward, persistent and smooth – yet modern, as he avoids romantic clichés with minimal vibrato, steady pacing and constant dynamics. In a sense, he melds Busch’s fundamentally respectful discretion with tantalizing hints of Cortot’s tangible spirit of outgoing commitment.

A 1949 set led by Fritz Reiner  gave a final push toward the explosion of modern interest by populating the nameless "Chamber Group" of his Brandenburgs (Columbia LPs) with American superstars, including Julius Baker on flute, Robert Bloom on oboe, William Lincer on viola, Leonard Rose on cello. Egos were minimized by spreading the solo turns – Sylvia Marlowe and Fernando Valente traded harpsichord roles and the movements of the Fourth feature different flautists. In keeping with Reiner's reputation as a precisionist, the playing throughout is meticulous and refined, without ever becoming fussy or precious. Nor is it boringly uniform or self-consciously rigid, amply projecting the personality of each movement, with an ear-splitting trumpet in the Second and unabashedly moving from a heartfelt middle movement to a rollicking conclusion of the Sixth. The only seeming romantic indulgence – an extreme slowdown at the end of the first movement of the Third – is logically convincing, as it leads smoothly into the two lingering transitional chords that comprise the entirety of Reiner's andante. Marlowe's measured harpsichord cadenza in the Fifth is enlivened with a striking change in register for the middle portion. But beyond the details, Reiner's readings point the way to restoring a sense of sheer musicianship which, more than any other element, is all that is needed to convey the glory of Bach. gave a final push toward the explosion of modern interest by populating the nameless "Chamber Group" of his Brandenburgs (Columbia LPs) with American superstars, including Julius Baker on flute, Robert Bloom on oboe, William Lincer on viola, Leonard Rose on cello. Egos were minimized by spreading the solo turns – Sylvia Marlowe and Fernando Valente traded harpsichord roles and the movements of the Fourth feature different flautists. In keeping with Reiner's reputation as a precisionist, the playing throughout is meticulous and refined, without ever becoming fussy or precious. Nor is it boringly uniform or self-consciously rigid, amply projecting the personality of each movement, with an ear-splitting trumpet in the Second and unabashedly moving from a heartfelt middle movement to a rollicking conclusion of the Sixth. The only seeming romantic indulgence – an extreme slowdown at the end of the first movement of the Third – is logically convincing, as it leads smoothly into the two lingering transitional chords that comprise the entirety of Reiner's andante. Marlowe's measured harpsichord cadenza in the Fifth is enlivened with a striking change in register for the middle portion. But beyond the details, Reiner's readings point the way to restoring a sense of sheer musicianship which, more than any other element, is all that is needed to convey the glory of Bach.

Aside from these full sets, we have several individual Brandenburgs of historical significance.

Although Arturo Toscanini recorded only a single slice of Bach in the studio, we have a 1938 NBC Symphony concert of the Brandenburg # 2 that's crude, brusque and with no pretense of style. Treating the polyphony as if it were a straggler from the classical era, all solos stand out from the fabric with raised volume, although the trumpet generally overwhelms the texture (and sounds if it adds a mute for some, but not all, of its accompanying figures) and the poor bassoon is mostly lost altogether. The andante survives largely intact, possibly because Toscanini leaves his three soloists and a cello on their own. A significant contrast is found in a far more pliant broadcast of the Brandenburg # 5 by the same orchestra only three years earlier under Frank Black with pianist Harold Samuel (Koch CD), thus attesting that Toscanini's only Brandenburg wasn't a rare lapse in preparation or taste but a conscious approach – and an unexpected disappointment, in strong contrast to his meltingly beautiful 1946 studio Air on the G String in which the lines blend exquisitely and each phrase swells with subtle dynamic inflection. recorded only a single slice of Bach in the studio, we have a 1938 NBC Symphony concert of the Brandenburg # 2 that's crude, brusque and with no pretense of style. Treating the polyphony as if it were a straggler from the classical era, all solos stand out from the fabric with raised volume, although the trumpet generally overwhelms the texture (and sounds if it adds a mute for some, but not all, of its accompanying figures) and the poor bassoon is mostly lost altogether. The andante survives largely intact, possibly because Toscanini leaves his three soloists and a cello on their own. A significant contrast is found in a far more pliant broadcast of the Brandenburg # 5 by the same orchestra only three years earlier under Frank Black with pianist Harold Samuel (Koch CD), thus attesting that Toscanini's only Brandenburg wasn't a rare lapse in preparation or taste but a conscious approach – and an unexpected disappointment, in strong contrast to his meltingly beautiful 1946 studio Air on the G String in which the lines blend exquisitely and each phrase swells with subtle dynamic inflection.

Wilhelm Furtwängler, too, recorded the Air on the G String (in 1929) with a style equally removed from accepted Baroque practice, yet with a clear difference – his is far slower and more spiritual, a deeply moving meditation rather than a perfunctory abstraction. His 1930 Berlin Philharmonic recording of the Brandenburg # 3 follows suit with a rich, full string section in which balances and dynamics constantly underscore the logical unfolding of the first movement. Furtwängler considered Bach as subjective as any Romantic composer, but self-contained with all emotion embedded deeply within his work. With subtle variations of tempo and volume, including an entire pianissimo section and two gradual buildups, Furtwängler eschews Bach's sudden shifts by enhancing the constant sequencing of repeated short figures and creating tangible and meaningful suspense, all without disrupting the fundamental uniformity of the texture. It's an interpretation, to be sure, but one that fully respects the spirit of the original. Far different are his 1950 Vienna Philharmonic concerts of the Third and Fifth Brandenburgs (Recital Records LP) – measured, solemn, richly romanticized and as far from idiomatic as can be imagined, seemingly closer to Wagner than anything Baroque. Yet on their own terms they are magnificent, infused with deeply personal feeling – every phrase is individually shaped amid vast shifts of tempos and dynamics, with exquisitely tender lyrical passages bracketed by emphatic transitions underscored with imposing piano chords. At the keyboard in the Fifth is Furtwängler himself, who provides a somewhat crude but profoundly moving cadenza. While disquieting to those who crave historical authenticity, these fascinating interpretations typify Furtwängler’s irrepressible urge to internalize and reconceive all music on his own highly personal terms – an extreme example, perhaps, yet a compelling souvenir of the manner in which later generations tended to mold Bach to conform with their own artistic impulses. recorded the Air on the G String (in 1929) with a style equally removed from accepted Baroque practice, yet with a clear difference – his is far slower and more spiritual, a deeply moving meditation rather than a perfunctory abstraction. His 1930 Berlin Philharmonic recording of the Brandenburg # 3 follows suit with a rich, full string section in which balances and dynamics constantly underscore the logical unfolding of the first movement. Furtwängler considered Bach as subjective as any Romantic composer, but self-contained with all emotion embedded deeply within his work. With subtle variations of tempo and volume, including an entire pianissimo section and two gradual buildups, Furtwängler eschews Bach's sudden shifts by enhancing the constant sequencing of repeated short figures and creating tangible and meaningful suspense, all without disrupting the fundamental uniformity of the texture. It's an interpretation, to be sure, but one that fully respects the spirit of the original. Far different are his 1950 Vienna Philharmonic concerts of the Third and Fifth Brandenburgs (Recital Records LP) – measured, solemn, richly romanticized and as far from idiomatic as can be imagined, seemingly closer to Wagner than anything Baroque. Yet on their own terms they are magnificent, infused with deeply personal feeling – every phrase is individually shaped amid vast shifts of tempos and dynamics, with exquisitely tender lyrical passages bracketed by emphatic transitions underscored with imposing piano chords. At the keyboard in the Fifth is Furtwängler himself, who provides a somewhat crude but profoundly moving cadenza. While disquieting to those who crave historical authenticity, these fascinating interpretations typify Furtwängler’s irrepressible urge to internalize and reconceive all music on his own highly personal terms – an extreme example, perhaps, yet a compelling souvenir of the manner in which later generations tended to mold Bach to conform with their own artistic impulses.

Leopold Stokowski led the Philadelphia Orchestra and harpsichordist Fernando Valenti in what could be the most unabashedly romantic Fifth on record, full of emphatic slowdowns to mark transition points and endings and a very slow (but undeniably moving) middle movement that distends Bach's affettuoso to a lethargic extreme. Taken on its own terms it's a lovely and heartfelt performance in which the rich instrumentation becomes seductive, the committed playing of the violin and flute solos are sincere and the harpsichord lurks teasingly in the deep background until it emerges to assert itself in the cadenza. While hardly authentic, it's refreshingly chaste when compared to Stokowski's syrupy orchestral arrangements of other Bach works, including three organ Chorale Preludes, which filled out the original LP. led the Philadelphia Orchestra and harpsichordist Fernando Valenti in what could be the most unabashedly romantic Fifth on record, full of emphatic slowdowns to mark transition points and endings and a very slow (but undeniably moving) middle movement that distends Bach's affettuoso to a lethargic extreme. Taken on its own terms it's a lovely and heartfelt performance in which the rich instrumentation becomes seductive, the committed playing of the violin and flute solos are sincere and the harpsichord lurks teasingly in the deep background until it emerges to assert itself in the cadenza. While hardly authentic, it's refreshingly chaste when compared to Stokowski's syrupy orchestral arrangements of other Bach works, including three organ Chorale Preludes, which filled out the original LP.

Like Furtwängler, Pablo Casals approached Bach philosophically, yet more personally. His daily routine began by playing two of Bach's preludes and fugues and a cello suite, from which he took constant inspiration.  He felt that Bach's music expressed all the feelings of the human soul, and considered the St. Matthew Passion to be the most sublime masterpiece in all of music. Casals was one of the very few conductors, and certainly the first, to record the complete Brandenburgs twice – in 1950 with his Prades Festival Orchestra (Columbia LPs) and in 1964-6 with the Marlboro Festival Orchestra (Sony CDs). He felt that Bach's music expressed all the feelings of the human soul, and considered the St. Matthew Passion to be the most sublime masterpiece in all of music. Casals was one of the very few conductors, and certainly the first, to record the complete Brandenburgs twice – in 1950 with his Prades Festival Orchestra (Columbia LPs) and in 1964-6 with the Marlboro Festival Orchestra (Sony CDs).  Incidentally, don't be fooled by their names into assuming that these were amateur ensembles – both were extraordinary groups of top-flight professionals who would come together to study and play over the summer – the cello section of the Marlboro Festival Orchestra included Mischa Schneider (of the Budapest Quartet), Hermann Busch (Busch Quartet) and David Soyer (Guarneri Quartet). As recalled by Bernard Meillat, while Casals appreciated research into Baroque playing, he viewed Bach as timeless and universal, and insisted that an interpreter's intuition was far more important than strict observance of esthetic tradition. Thus, he shunned old instruments and used a piano rather than the harpsichord heard on every other stereo Brandenburg simply because he found the resources of the piano to be far more expressive. He was also practical, substituting a soprano saxophone in the 1950 Second, not for any artistic reason but simply because the specified trumpet couldn't keep up with his breakneck pace, the fastest on record. While his tempos can be extreme, Casals' precise phrasing and subtle inflection constantly enliven his work, which emerges as warm, rich and intensely human – not surprisingly, the very qualities that distinguished his celebrated performances as the most influential of all cellists. Incidentally, don't be fooled by their names into assuming that these were amateur ensembles – both were extraordinary groups of top-flight professionals who would come together to study and play over the summer – the cello section of the Marlboro Festival Orchestra included Mischa Schneider (of the Budapest Quartet), Hermann Busch (Busch Quartet) and David Soyer (Guarneri Quartet). As recalled by Bernard Meillat, while Casals appreciated research into Baroque playing, he viewed Bach as timeless and universal, and insisted that an interpreter's intuition was far more important than strict observance of esthetic tradition. Thus, he shunned old instruments and used a piano rather than the harpsichord heard on every other stereo Brandenburg simply because he found the resources of the piano to be far more expressive. He was also practical, substituting a soprano saxophone in the 1950 Second, not for any artistic reason but simply because the specified trumpet couldn't keep up with his breakneck pace, the fastest on record. While his tempos can be extreme, Casals' precise phrasing and subtle inflection constantly enliven his work, which emerges as warm, rich and intensely human – not surprisingly, the very qualities that distinguished his celebrated performances as the most influential of all cellists.

Among many complete sets of the Brandenburgs using modern instruments, I've enjoyed those by Jascha Horenstein and the Vienna Symphony Orchestra (Vox, 1954), Paul Sacher and the Chamber Orchestra of Basel (Epic, 1956), Hermann Scherchen and the Vienna Symphony Orchestra (Westminster, 1957), Yehudi Menuhin and the Bath Festival Chamber Orchestra (EMI, 1959), Karl Munchinger and the Stuttgart Chamber Orchestra (London, 196X), Otto Klemperer and the Philharmonia (EMI, 1962), Karl Ristenpart and the Chamber Orchestra of the Saar (Nonesuch, 1966), Benjamin Britten and the English Chamber Orchestra (London, 1968), Jean François Paillard and the Paillard Chamber Orchestra (RCA, 1972) and Herbert von Karajan and the Berlin Philharmonic (DG). I've enjoyed those by Jascha Horenstein and the Vienna Symphony Orchestra (Vox, 1954), Paul Sacher and the Chamber Orchestra of Basel (Epic, 1956), Hermann Scherchen and the Vienna Symphony Orchestra (Westminster, 1957), Yehudi Menuhin and the Bath Festival Chamber Orchestra (EMI, 1959), Karl Munchinger and the Stuttgart Chamber Orchestra (London, 196X), Otto Klemperer and the Philharmonia (EMI, 1962), Karl Ristenpart and the Chamber Orchestra of the Saar (Nonesuch, 1966), Benjamin Britten and the English Chamber Orchestra (London, 1968), Jean François Paillard and the Paillard Chamber Orchestra (RCA, 1972) and Herbert von Karajan and the Berlin Philharmonic (DG).  Among them, a few highlights. Scherchen leads a particularly leisurely First that seems somewhat emasculated, with beautiful balances, tamed horns, smooth layering of sound and dances that seamlessly glide into one another – quite surprising for a conductor so thoroughly versed in modern music, but perhaps an entirely appropriate attempt to restore the original intent of appealing to the most admiring instincts in a potential patron whose mores were saturated in the leisurely courtly pleasures of nobility. Menuhin is the most leisurely of the lot (110 minutes total, compared to a standard 100 or so for the older crowd and 90+ for the moderns), but enlivened with heartfelt expression, in keeping with his style as a famed solo violinist. Klemperer seems as straight-forward as could be imagined, yet his trademark sobriety serves to demonstrate that these works are so filled with intrinsic merit as to need no extra interpretive help to communicate their message to modern listeners. So, too, with Britten, Munchinger and Karajan, who adds his trademark gloss and precision to a richer, massed sonority that breathes ease and serenity, especially in the string concertos (#s 3 and 6). To complement his lovely pacing and sweet tone, Sacher's harpsichord is especially prominent, as if to emphasize the then-unfamiliar period feel. My favorite among them is the Ristenpart, for three reasons – it was the first set of Brandenburgs I ever bought (probably for its budget price – $4 meant a lot to me back then), Among them, a few highlights. Scherchen leads a particularly leisurely First that seems somewhat emasculated, with beautiful balances, tamed horns, smooth layering of sound and dances that seamlessly glide into one another – quite surprising for a conductor so thoroughly versed in modern music, but perhaps an entirely appropriate attempt to restore the original intent of appealing to the most admiring instincts in a potential patron whose mores were saturated in the leisurely courtly pleasures of nobility. Menuhin is the most leisurely of the lot (110 minutes total, compared to a standard 100 or so for the older crowd and 90+ for the moderns), but enlivened with heartfelt expression, in keeping with his style as a famed solo violinist. Klemperer seems as straight-forward as could be imagined, yet his trademark sobriety serves to demonstrate that these works are so filled with intrinsic merit as to need no extra interpretive help to communicate their message to modern listeners. So, too, with Britten, Munchinger and Karajan, who adds his trademark gloss and precision to a richer, massed sonority that breathes ease and serenity, especially in the string concertos (#s 3 and 6). To complement his lovely pacing and sweet tone, Sacher's harpsichord is especially prominent, as if to emphasize the then-unfamiliar period feel. My favorite among them is the Ristenpart, for three reasons – it was the first set of Brandenburgs I ever bought (probably for its budget price – $4 meant a lot to me back then), it had wonderfully witty gatefold cover art by Roger Hane that helped deflate the prevalent image of a bewigged, prehistoric relic with nothing to say to the rock generation, and because in retrospect its lean textures and vivid recording heralded the genuine Baroque style and sonority that had only begun to emerge. (The somewhat crude Horenstein set, from a decade earlier, featured a similarly spare sonority before any of the authentic instrument versions and thus was way ahead of its time. A clear beneficiary of the developing trend, Paillard takes his cue, if not his instruments, from the historically-informed fashion with a bright, thin sound.) it had wonderfully witty gatefold cover art by Roger Hane that helped deflate the prevalent image of a bewigged, prehistoric relic with nothing to say to the rock generation, and because in retrospect its lean textures and vivid recording heralded the genuine Baroque style and sonority that had only begun to emerge. (The somewhat crude Horenstein set, from a decade earlier, featured a similarly spare sonority before any of the authentic instrument versions and thus was way ahead of its time. A clear beneficiary of the developing trend, Paillard takes his cue, if not his instruments, from the historically-informed fashion with a bright, thin sound.)

The notes to the Menuhin set (which boast of such recording "tricks" as miking the harpsichord from below in order to mask its characteristic extraneous noises) conclude with the absurd "hope that … we have presented a definitive recording that will outlast all the rest." Fortunately, that didn't happen, as the next decade brought a fabulous bounty that has immeasurably enriched our understanding of the Brandenburgs.

While standing on their own musical merit, a credible rationale for performances of the Brandenburg Concertos with full orchestras and/or modern instruments is that Bach had fully exploited the forces available in his time and would gladly have embraced the greater resources of the modern era. Yet, the fact remains that Bach lived when he did, heard sounds far different from ours, and conceived his work on that basis. The vast majority of stereo Brandenburgs attempt to varying degrees to evoke the aesthetics of Bach's time to replicate the way he intended his work to be presented. While standing on their own musical merit, a credible rationale for performances of the Brandenburg Concertos with full orchestras and/or modern instruments is that Bach had fully exploited the forces available in his time and would gladly have embraced the greater resources of the modern era. Yet, the fact remains that Bach lived when he did, heard sounds far different from ours, and conceived his work on that basis. The vast majority of stereo Brandenburgs attempt to varying degrees to evoke the aesthetics of Bach's time to replicate the way he intended his work to be presented.

A 1964 set by Nikolaus Harnoncourt and the Concentus Musicus Wein (Telefunken) claimed to be the first on authentic instruments. Perhaps as a function of its historical importance, in his accompanying notes, Harnoncourt took great pains to justify his efforts to recreate an authentic Baroque sound.  His foundation is composer Paul Hindemith, whose 1922-27 Kammermusik was a set of seven concertos intended to invoke the spirit of the Brandenburgs, and who insisted that Bach delighted in balancing the weight and sound of the stylistic media at his disposal rather than regarding the limited resources of his era as a hindrance. Harnoncourt goes on to reject the then-prevalent traditional view that old instruments were merely an imperfect preliminary stage in the development of modern ones, insisting instead that their essence lies in a completely different (but equally valid) relationship of sound and balance. He notes that every "improvement" has to be paid for with a deterioration, and that the evolution of instruments suits composers' changing demands and audiences' changing taste. He catalogues the different sonorities of the instruments Bach composed for – overall, they were quieter, sharper, more colorful, with richer overtones and more distinctive sonorities; in particular, the harpsichord was louder, more intense and occupied the central place in ensembles. He also notes that Baroque concert venues were of stone and marble with high ceilings, contributing far more resonance and blending of sound than modern settings of absorbent wood and carpet. The recordings themselves have a reedy, thinner sound than most others – strings (using only one player per part) are far less prominent and the winds and brass have a strong midrange presence that tends to meld their sounds. His foundation is composer Paul Hindemith, whose 1922-27 Kammermusik was a set of seven concertos intended to invoke the spirit of the Brandenburgs, and who insisted that Bach delighted in balancing the weight and sound of the stylistic media at his disposal rather than regarding the limited resources of his era as a hindrance. Harnoncourt goes on to reject the then-prevalent traditional view that old instruments were merely an imperfect preliminary stage in the development of modern ones, insisting instead that their essence lies in a completely different (but equally valid) relationship of sound and balance. He notes that every "improvement" has to be paid for with a deterioration, and that the evolution of instruments suits composers' changing demands and audiences' changing taste. He catalogues the different sonorities of the instruments Bach composed for – overall, they were quieter, sharper, more colorful, with richer overtones and more distinctive sonorities; in particular, the harpsichord was louder, more intense and occupied the central place in ensembles. He also notes that Baroque concert venues were of stone and marble with high ceilings, contributing far more resonance and blending of sound than modern settings of absorbent wood and carpet. The recordings themselves have a reedy, thinner sound than most others – strings (using only one player per part) are far less prominent and the winds and brass have a strong midrange presence that tends to meld their sounds.