|

|

Inspired by his love of nature, Beethoven’s Symphony # 6 (“Pastoral”) was among his most influential achievements. In this article we discuss its precedents, genesis, structure, influences, some performance considerations, and then notable recordings, including the pioneers, some especially creative approaches, historically-informed and hybrid readings, and (briefly) some others of interest. Finally, sources for this article are listed. |

|

Beethoven’s even-numbered symphonies often are deemed secondary to his odd-numbered ones, which, after all, include the indisputably momentous Eroica (#3), Fifth and Choral (#9). Yet Beethoven’s 1808 Symphony # 6 in F major (“Pastoral”), Op. 68, although seemingly more modest, is every bit as influential. Together with the Symphony # 5 in c-minor, Op. 67, it displays the two poles of his creative personality. which, after all, include the indisputably momentous Eroica (#3), Fifth and Choral (#9). Yet Beethoven’s 1808 Symphony # 6 in F major (“Pastoral”), Op. 68, although seemingly more modest, is every bit as influential. Together with the Symphony # 5 in c-minor, Op. 67, it displays the two poles of his creative personality.

The Fifth and Sixth Symphonies were written together, introduced to the world in the same marathon concert, and display certain superficial similarities – opening motifs, followed by pauses, that generate the first movements, thicker instrumentation as they progress, and final movements melded together. Yet, the Fifth surges with snarling minor-key tension and explodes in triumphant defeat of Beethoven’s demons, while the Sixth brims with gentle, poetic beauty and affirms the sheer splendor of nature and life.

The most direct inspiration for the Pastoral Symphony had no direct connection to music. Rather, it was Beethoven’s deep love of nature. Anthony Hopkins suggests that Beethoven moved so often within Vienna (rarely going a year without changing his residence) because he hated city living. Indeed, every summer he would move to the country.

The most direct inspiration for the Pastoral Symphony had no direct connection to music. Rather, it was Beethoven’s deep love of nature. Anthony Hopkins suggests that Beethoven moved so often within Vienna (rarely going a year without changing his residence) because he hated city living. Indeed, every summer he would move to the country.  Charles Neate, an English pianist who befriended Beethoven and spent the summer of 1815 taking long walks with him, recalled that he had never met anyone “who so delighted in Nature or so thoroughly enjoyed flowers or clouds or other natural objects.” Countess Theresa of Brunswick, a student and possibly intimate friend, wrote: “He loved to be alone with Nature, to make her his only confidante. When his brain was reeling with confused ideas, Nature at all times comforted him.” Others reported that Beethoven refused lodging without nearby trees, could not be dissuaded from long daily walks even in heavy rain (for which he refused an umbrella), that he wandered around jotting down themes in his ever-present sketchbooks, and that he assumed a frightening presence by lapsing into the appearance and behavior of a vagrant. Beethoven himself wrote in a letter: “How glad I am to be able to roam in wood and thicket, among the trees and flowers and rocks. No one can love the country as I do. … In the country every tree seems to speak to me, saying, ‘Holy! Holy!’ In the woods there is enchantment which expresses all things!” Charles Neate, an English pianist who befriended Beethoven and spent the summer of 1815 taking long walks with him, recalled that he had never met anyone “who so delighted in Nature or so thoroughly enjoyed flowers or clouds or other natural objects.” Countess Theresa of Brunswick, a student and possibly intimate friend, wrote: “He loved to be alone with Nature, to make her his only confidante. When his brain was reeling with confused ideas, Nature at all times comforted him.” Others reported that Beethoven refused lodging without nearby trees, could not be dissuaded from long daily walks even in heavy rain (for which he refused an umbrella), that he wandered around jotting down themes in his ever-present sketchbooks, and that he assumed a frightening presence by lapsing into the appearance and behavior of a vagrant. Beethoven himself wrote in a letter: “How glad I am to be able to roam in wood and thicket, among the trees and flowers and rocks. No one can love the country as I do. … In the country every tree seems to speak to me, saying, ‘Holy! Holy!’ In the woods there is enchantment which expresses all things!”

In the same letter, he also wrote, tellingly, “My bad hearing does not trouble me here.” That, in turn, provides a crucial key to his inspiration for the Pastoral, as well as the deep feeling he poured into it. In his heart-rending “Heiligenstadt Testament,” Beethoven cursed his growing deafness and begged indulgence of those “who take me or denounce me for morose, crabbed or misanthropical” behavior which “forced [me] to isolate myself to lead a solitary life” and made him “hasten to meet death face to face.”

Portait by August von Klober |

That was in 1802. A half-decade later his inability to communicate with his fellow men must have become even less bearable. (Eventually, he would seize upon the partial expediency of conversation books, in which visitors would write out their part of verbal exchanges.) Alone in the woods, he at last was spared any need for social interaction. Along with the fulfillment of his music, nature provided his overriding joy, and he could well imagine and take comfort in its sounds amid the oppressive silence of his bleak reality. Louis Biancolli summarizes its import as “a healing power for the torment of spirit and stress of daily living.” Donald Tovey wrote that the Pastoral Symphony “has the enormous strength of someone who knows how to relax.”

Anton Felix Shindler reported that Beethoven’s favorite book was a copy, dog-eared from use, of Christian Sturm’s Reflections on the Works of God in the Realm of Nature and Providence from which he copied passages such as: “One might rightly denominate Nature the school of the heart; she clearly shows us our duties toward God and our neighbor.” Basil Lam observes that Beethoven didn’t worship nature as a pantheist, but rather had a mystical belief that nature itself was worshipping God. Anton Schindler adds that Beethoven was fascinated by the elemental power of Nature, rather than its laws. In any event, as Biancolli asserts, the Pastoral was the deaf composer’s recollection of an audible past, transmuted into an idealized affirmation of life that transcended the throes of his terrible malady.

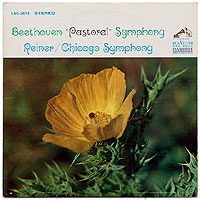

Alexander Wheelock Thayer asserted that Beethoven never wanted to invent new forms, but rather to surpass his contemporaries with existing ones. With specific reference to the popularity of descriptive music, he cracked: “There were few great battles in those stormy years that were not fought over again by orchestras, military bands, organs and pianofortes.” Alexander Wheelock Thayer asserted that Beethoven never wanted to invent new forms, but rather to surpass his contemporaries with existing ones. With specific reference to the popularity of descriptive music, he cracked: “There were few great battles in those stormy years that were not fought over again by orchestras, military bands, organs and pianofortes.”   Indeed, Haydn had done just that in his Symphony # 100 ("Military"), in which the second movement, fortified with a battery of “Turkish” percussion, depicts, in the words of a contemporary review, “the advancing to battle, the march of men, the sounding of the charge, the thundering of the onset, the clash of arms, the groans of the wounded and what may be called the hellish roar of war.” Nowadays, of course, the intensity seems far less extreme, but audiences of the time clearly were impressed, and Hopkins believes that Beethoven’s oft-cited admonition not to take the Pastoral literally was in reaction to such realistic effects. (Ironically, Beethoven’s greatest success would come with his 1813 Battle Symphony (“Wellington’s Victory”), a trashy pastiche originally written for a mechanical “panharmonicon” but then orchestrated with rattles, giant drums, cannons and musketry.) Indeed, Haydn had done just that in his Symphony # 100 ("Military"), in which the second movement, fortified with a battery of “Turkish” percussion, depicts, in the words of a contemporary review, “the advancing to battle, the march of men, the sounding of the charge, the thundering of the onset, the clash of arms, the groans of the wounded and what may be called the hellish roar of war.” Nowadays, of course, the intensity seems far less extreme, but audiences of the time clearly were impressed, and Hopkins believes that Beethoven’s oft-cited admonition not to take the Pastoral literally was in reaction to such realistic effects. (Ironically, Beethoven’s greatest success would come with his 1813 Battle Symphony (“Wellington’s Victory”), a trashy pastiche originally written for a mechanical “panharmonicon” but then orchestrated with rattles, giant drums, cannons and musketry.)

But Beethoven’s concerns lay elsewhere, and there was ample precedent for that as well. Barry Cooper notes that throughout the prior century a pastoral style had crystallized, featuring gentle moods, homophonic textures, prominent use of woodwinds, drone basses, simple harmonies, major keys (especially F and G), lyrical or dance-like melodies in conjunct motion, compound meters and occasional imitations of bird songs and horn calls. Examples included a 1799 piano concerto by Daniel Steibelt (subtitled, “The Storm, Preceded by a Pastorale Rondo”), a late 18th century organ piece by Justin Heinrich Knecht and popularized by Georg Joseph Vogler, “The Shepherd’s Pleasure, Interrupted by a Storm,” Haydn’s Symphonies 6, 7 and 8 (“Morning,” “Noon” and “Night,” which begins with a brief allusion to sunrise and ends with a storm) and, of course, Vivaldi's Four Seasons, with close line-by-line depictions of four sonnets whose text is written into the score at the appropriate spots. Roger Norrington also cites as inspiration the huge popularity of Haydn’s 1801 Seasons oratorio, which shared Beethoven’s overall feeling of joy in contemplating the natural world, even though Volker Scherheiss distinguishes the earlier models as a largely stylized, impersonal depiction of an artificial mythological world of nymphs and demigods.

But the most direct precedent was Knecht's 1784 Grande sinfonie, which he entitled “Portrait musical de la nature (Pastoralsymphonie).” It comprised five movements:

I. A beautiful country where the sun is shining, brooks traverse the vale, the birds twitter, a waterfall tumbles from the mountain, the shepherd plays his pipe, the lambs gambol around; and there the sweet voice of the shepherdess is heard.

II. Suddenly the sky is overcast, an oppressive closeness pervades the air, black clouds pile up, the wind rises, thunder is heard from afar, and the storm approaches.

III. The tempest bursts in all its fury. The wind howls and the rain beats down. The trees groan and the waters of the streams rush furiously.

IV. The storm gradually subsides, the clouds disperse, and the sky becomes clear.

V. Nature raises its joyful voice to heaven in song of gratitude to the Creator.

Although forgotten nowadays, Beethoven surely knew this work, as an advertisment for it, including the descriptions, appeared on the back page of three of his early piano sonatas (WoO 47), which was issued by the same publisher. While Knecht’s Haydnesque symphony adhered closely to classical models and placed greater emphasis on the storm (albeit a highly stylized one), the similarity of its program to that of the Pastoral is striking.

Although completed in the summer of 1808 in Weisenthal, near Heiligenstadt (now a suburb of Vienna, but then a rural resort on the bank of the Danube), sketches for the Pastoral are found in Beethoven’s notebooks as early as 1803. The most telling are two attempts that year to transcribe the sound of a stream, which eventually would emerge as the undulating introduction to the second movement. But as Leopold Stokowski demonstrated in a “Sounds of Nature” lecture appended to his 1954 recording, the actual sound of a gurgling brook (and actual bird calls and thunderstorms) bear scant resemblance to Beethoven’s adaptation of these stimuli in his symphony. Although completed in the summer of 1808 in Weisenthal, near Heiligenstadt (now a suburb of Vienna, but then a rural resort on the bank of the Danube), sketches for the Pastoral are found in Beethoven’s notebooks as early as 1803. The most telling are two attempts that year to transcribe the sound of a stream, which eventually would emerge as the undulating introduction to the second movement. But as Leopold Stokowski demonstrated in a “Sounds of Nature” lecture appended to his 1954 recording, the actual sound of a gurgling brook (and actual bird calls and thunderstorms) bear scant resemblance to Beethoven’s adaptation of these stimuli in his symphony.  Although, as we will note, Beethoven provided descriptive titles for each movement, at the same time he cautioned against interpreting his intentions literally. Thus, he wrote in his sketchbooks: “The hearers should be allowed to discover the situations.” “All painting in instrumental music, if pushed too far, is a failure.” “Anyone who has an idea of country life can make out for himself the intentions of the author without many titles.” “People will not require titles to recognize the general intention to be more a matter of feeling than of painting in sounds.” “Pastoral Symphony: no picture but something in which the emotions are expressed which are aroused in men by the pleasure of the country, in which some feelings of country-life are set forth.” “A recollection of country life.” As Lewis Lockwood noted, it seems as though Beethoven wanted to take advantage of the taste for illustrative composition while elevating it beyond mere mimickry and sound effects. Yet, as Hopkins notes, music ultimately is about music; as a self-contained art, it has little need of association with words. Although, as we will note, Beethoven provided descriptive titles for each movement, at the same time he cautioned against interpreting his intentions literally. Thus, he wrote in his sketchbooks: “The hearers should be allowed to discover the situations.” “All painting in instrumental music, if pushed too far, is a failure.” “Anyone who has an idea of country life can make out for himself the intentions of the author without many titles.” “People will not require titles to recognize the general intention to be more a matter of feeling than of painting in sounds.” “Pastoral Symphony: no picture but something in which the emotions are expressed which are aroused in men by the pleasure of the country, in which some feelings of country-life are set forth.” “A recollection of country life.” As Lewis Lockwood noted, it seems as though Beethoven wanted to take advantage of the taste for illustrative composition while elevating it beyond mere mimickry and sound effects. Yet, as Hopkins notes, music ultimately is about music; as a self-contained art, it has little need of association with words.

Even so, as Franz Liszt would later observe, since musical language “is more arbitrary and more uncertain than any other … and lends itself to the most varied interpretations, it is not without value … for the composer to give in a few lines the spiritual sketch of his work and, without falling into petty and detailed explanations, convey the idea which served as the basis for his composition. … This will prevent faulty elucidations, hazardous interpretations, idle quarrels with intentions the composer never had, and endless commentaries which rest on nothing.” (Yet it could be argued that the splendor of music lies in that very quality – that it affects each hearer in different, personal ways, even if the composer never intended them.)  Notwithstanding the limited scope of Beethoven’s hints and Liszt’s cautions, many authors have felt compelled to inflate Beethoven's brief captions with expansive “interpretations” of the Pastoral, not the least of whom was Hector Berlioz, whose Critical Study of Beethoven’s Nine Symphonies attempts to assign a specific narrative function to virtually each phrase. Typical is his exegesis of the first movement: “The herdsmen begin to appear in the fields. They have their usual careless manner and the sound of their pipes proceeds from far to near. … Swarms of chattering birds in flight pass rustling overhead. … Great clouds appear and hide the sun, then, all at once, they disappear, and there suddenly falls upon both tree and wood the torrent of a dazzling light.” (Such effusion seems all the more curious, as Berlioz graced the five movements of his Symphonie Fantastique with even shorter titles than Beethoven's.) Notwithstanding the limited scope of Beethoven’s hints and Liszt’s cautions, many authors have felt compelled to inflate Beethoven's brief captions with expansive “interpretations” of the Pastoral, not the least of whom was Hector Berlioz, whose Critical Study of Beethoven’s Nine Symphonies attempts to assign a specific narrative function to virtually each phrase. Typical is his exegesis of the first movement: “The herdsmen begin to appear in the fields. They have their usual careless manner and the sound of their pipes proceeds from far to near. … Swarms of chattering birds in flight pass rustling overhead. … Great clouds appear and hide the sun, then, all at once, they disappear, and there suddenly falls upon both tree and wood the torrent of a dazzling light.” (Such effusion seems all the more curious, as Berlioz graced the five movements of his Symphonie Fantastique with even shorter titles than Beethoven's.)

Unlike the vast majority of assumed names by which his works have become known, Beethoven directed from the very outset that his sixth symphony be titled “Pastoral Symphony, or a recollection of country life. More an expression of feeling than a painting.” The label is found in a letter Beethoven sent to his publisher in 1809 and, together with the titles of each movement, on the program book of the first performance and on the engraved first violin part. (Until 1825, when the full score was first published, only the parts were issued.)

Among the other conventions it flouted, the Pastoral expanded the established standard of four symphonic movements into five, a triumph of content over form when an esthetic impulse so dictated. Among the other conventions it flouted, the Pastoral expanded the established standard of four symphonic movements into five, a triumph of content over form when an esthetic impulse so dictated.

“Erwachen heiterer Gefühle bei der Ankunft auf dem Lande” (“Awakening of cheerful feelings upon arrival in the country”) – Beethoven draws us in immediately with a gorgeous flowing theme (with a harmonized tail) over a rustic open-fifth drone (think: bagpipes), briefly teases us with a pause as if lingering on the threshold, and then opens the door wide to a warm and irresistible invitation to join him as he enters nature’s realm. “Erwachen heiterer Gefühle bei der Ankunft auf dem Lande” (“Awakening of cheerful feelings upon arrival in the country”) – Beethoven draws us in immediately with a gorgeous flowing theme (with a harmonized tail) over a rustic open-fifth drone (think: bagpipes), briefly teases us with a pause as if lingering on the threshold, and then opens the door wide to a warm and irresistible invitation to join him as he enters nature’s realm.

The opening of the first movement |

As Michael Steinberg observes, we barely hear the music start at all, as if nature were there all the time and we just came within earshot; indeed, he notes that while this imperceptible beginning would develop into an important Romantic device, Beethoven invented it right here. As becomes immediately apparent after the pause, the opening was no mere introduction, but rather the basic material from which the entire movement will evolve. Lam marvels that, while adhering to sonata form, Beethoven foregoes its essential tension and conflict in favor of a vast simplification into harmonic stretches of major chords that would not be heard again until Wagner.

The most intriguing commentaries analogize this musical approach to the forces of nature that inspired Beethoven. Thus, George Grove observes that each scrap of the opening germinates phrases directly related in rhythm or interval, much as nature itself repeats the same basic materials in infinite variety, without weariness or monotony. Perhaps the most extensive correlation of the opening movement to the processes and rhythms of nature is given by Hopkins, who analogizes the opening phrase to breathing (inhaling during the first three bars and then exhaling through the fermata), and its development to sunlight itself, of which variants produce shadows and reflections. He cites in particular bars 16-25, in which all the notes are absolutely identical, but with constant variation of dynamics, resulting in no hint of boredom while reflecting the fascinating repetition constantly found throughout nature. (Indeed, in the development section that same jaunty five-note motif, derived from the second bar of the introduction, is repeated incessantly for 36 bars (151-186) and then with barely a respite once again (197-232).) Hopkins further hears in the simultaneity of rapid figures and long, sustained notes a forest teeming with life amid an impression of vast stillness and attributes the occasional abrupt shifts in harmony (in lieu of transitions) to a succession of tonal vistas, as if Beethoven were standing in contemplation of a landscape and then turning to take in another view. He even likens the smoothing into triplets of the dotted rhythm of the opening figure to the relaxing effect of the scene upon the composer’s temperament.

“Szene am Bach” (“Scene by the brook”) – The mood of calm contentment continues as the strings introduce a lovely motif to invoke a gently babbling brook – as Lam notes, an ideal aural image that is still yet always flowing, drawing us into a state of timeless contemplation. Its precursor is found in Beethoven’s earliest 1803 sketches for this work – two jottings labeled “murmur of the stream” and “the more water the deeper the tone.” “Szene am Bach” (“Scene by the brook”) – The mood of calm contentment continues as the strings introduce a lovely motif to invoke a gently babbling brook – as Lam notes, an ideal aural image that is still yet always flowing, drawing us into a state of timeless contemplation. Its precursor is found in Beethoven’s earliest 1803 sketches for this work – two jottings labeled “murmur of the stream” and “the more water the deeper the tone.”

The opening of the second movement |

Beethoven keeps the texture of the opening rich but light by using only two muted cellos with the second violins and violas, while the first violins flit above with bird-like phrases (and thus provide an immediate harbinger of the conclusion, which has attracted much critical comment and even ridicule). Thus, barely a minute from the end, the steady lilting activity halts and, notwithstanding his own admonitions, Beethoven introduces three bird-songs – a nightingale in the flutes, a quail in the oboes and a cuckoo in the clarinets – and lest there be any doubt, he actually labels each one in the score.

Many commentators have offered rationales for this seemingly patent violation of Beethoven’s clearly-expressed intention to view the Pastoral figuratively. Berlioz noted that the depictions of birds’ variable sounds really aren’t literal (except for the cuckoo, which does repeatedly sound only two notes). Tovey adds that in nature birds would keep repeating their calls when they are happy. Grove contends that the bird calls were meant as a practical joke and thus were consistent with Beethoven’s reproach. Cooper asserts that the calls are meant symbolically as an expression of nature’s praise of God.

The birds of the second movement |

Noting that the bird songs are perfectly integrated into the prevailing meter, Claus Roy asserts that the episode functions as a cadenza, to which Lam adds that the birds assume the role of resident musicians at the stream, and Steinberg cites it as but one illustration of the wonder of the Pastoral as “a beautifully gauged mix of the explicit and the suggestive.”

That, in turn, invokes a much-discussed anecdote. According to Schindler (the reliability of whose biography has often been questioned), in late April 1823 they were walking near Heiligenstadt when Beethoven pointed out the spot where he wrote the “Scene by the Brook” and specifically recalled the yellow-hammers (i.e.: goldfinches), quails, nightingales and cuckoos who had “composed along with him.” Schindler claims that when he asked Beethoven why he had not put the yellow-hammers into the scene, he seized his sketchbook and wrote out the notes of a two-octave G-major chord, explaining that he had already written the scale into the work [in the flute arpeggios beginning at bar 58?] and didn’t want to label it for fear that “such a thing would only have added to the great number of malicious interpretations that had already hampered the reception and reputation of the work in Vienna and elsewhere. All too frequently the symphony had been denounced as a burlesque because of the second movement.” A good story, perhaps, but, as Thayer points out, yellow-hammers sing a quick succession of the same note – about as far removed as possible from a two-octave scale! Thayer asserts that Beethoven had no patience for stupid questions and was pulling the fawning Schindler’s leg with an intentionally nonsensical answer. Hopkins, though, takes Beethoven’s answer figuratively, in the sense that in fact he had scattered sublimated bird calls (and perhaps other sounds of nature) throughout the work and that Schindler (and others) should listen more attentively.  Indeed, Tovey proclaims the movement “one of the most powerful things in music” – in full, traditionally-proportioned sonata form yet flowing so freely with associations that at every point it “asserts its deliberate intention to be lazy and say whatever comes to it,” a perfect depiction of “the poet’s mood and the way his thoughts and utterances gradually take shape.” Perhaps more than any other part of this work, the casual, rambling second movement liberates musical expression from formal constraints. Indeed, Tovey proclaims the movement “one of the most powerful things in music” – in full, traditionally-proportioned sonata form yet flowing so freely with associations that at every point it “asserts its deliberate intention to be lazy and say whatever comes to it,” a perfect depiction of “the poet’s mood and the way his thoughts and utterances gradually take shape.” Perhaps more than any other part of this work, the casual, rambling second movement liberates musical expression from formal constraints.

“Lustiges Zusammensein der Landleute” (“Merry gathering of the country folk”) – Here, we encounter people for the first time, intruding upon the earlier idyll with a lusty peasant dance (although not for long – nature will soon reassert itself to show who’s really the boss). We also have a rare instance of Beethoven’s humor – a bassoon that plays only two tones (tonic and dominant). Schindler claims that this was meant as mimickry of a tired village bassoonist who sporadically wakens from his slumber by instinctively playing a few basic notes, and that the entire movement was meant to emulate the seven-member band at Beethoven’s favorite country inn, the “Three Ravens,” for which he had written a number of dances. (Schindler further notes that the theme was inspired by a popular Austrian dance of the time, but others assert that the first written evidence of such a dance arose only decades later and thus the dance could have been derived from Beethoven’s movement – if so, an intriguing reversal of the usual flow of thematic inspiration from folk to serious music.) William Drabkin notes that the unusual structure of the movement – a full repeat of both the 3/4 scherzo and two 2/4 trios followed by an abridgement of the opening 3/4 section – was needed to expand its scale to suit the rest of the symphony. Perhaps the most remarkable feature, though, is the abrupt ending – the dance rises to a vigorous F-major cadence and then tries to repeat the figure but instead abruptly breaks off the attempt and plunges into f-minor for a sudden shift to: “Lustiges Zusammensein der Landleute” (“Merry gathering of the country folk”) – Here, we encounter people for the first time, intruding upon the earlier idyll with a lusty peasant dance (although not for long – nature will soon reassert itself to show who’s really the boss). We also have a rare instance of Beethoven’s humor – a bassoon that plays only two tones (tonic and dominant). Schindler claims that this was meant as mimickry of a tired village bassoonist who sporadically wakens from his slumber by instinctively playing a few basic notes, and that the entire movement was meant to emulate the seven-member band at Beethoven’s favorite country inn, the “Three Ravens,” for which he had written a number of dances. (Schindler further notes that the theme was inspired by a popular Austrian dance of the time, but others assert that the first written evidence of such a dance arose only decades later and thus the dance could have been derived from Beethoven’s movement – if so, an intriguing reversal of the usual flow of thematic inspiration from folk to serious music.) William Drabkin notes that the unusual structure of the movement – a full repeat of both the 3/4 scherzo and two 2/4 trios followed by an abridgement of the opening 3/4 section – was needed to expand its scale to suit the rest of the symphony. Perhaps the most remarkable feature, though, is the abrupt ending – the dance rises to a vigorous F-major cadence and then tries to repeat the figure but instead abruptly breaks off the attempt and plunges into f-minor for a sudden shift to:

“Gewitter, Sturm” (“Storm, Tempest”) – Far too many commentators go on at length about this “realistic” depiction of a violent summer storm, but they miss the point (as does Sigmund Spaeth, who complains that it “is not particularly convincing”). “Gewitter, Sturm” (“Storm, Tempest”) – Far too many commentators go on at length about this “realistic” depiction of a violent summer storm, but they miss the point (as does Sigmund Spaeth, who complains that it “is not particularly convincing”).

The unrest of the storm

Cellos in 5 against basses in 4 |

Although the soft tympani rolls may depict receding thunder, there is nothing real about thunder preceding lightning, four peals of thunder arriving in strict rhythmic succession, or a loud sound sustained for five seconds. Rather, consistent with the rest of the symphony, this is a poet’s deliberately vague attempt to prompt a human response to the elements of a natural event. As Steinberg notes, its power lies in its classical precision and economy that stimulate our imagination and thus emerges as more powerful than the more literal depictions of Wagner, Verdi and Strauss using far more lavish physical forces. Augmenting the instruments used so far, Beethoven adds a piccolo, trombones and tympani, but he deploys them sparingly while using conventional resources in unconventional ways, most notably juxtaposing cellos in 5 against basses in 4 to create scalar runs that keep diverging to shake the sound by the very roots of its foundation. In purely musical terms, Cooper attributes the impact of this movement to its tonal instability, with much use of diminished sevenths and the absence of a standard pattern of phrase lengths. While Berlioz hailed it as “no longer merely wind and rain but an awful cataclysm, the universal deluge, the end of the world,” Roy acclaims it “the best storm music in the entire literature, simply because it is the best music.” The movement ends in a ravishing transition of a gently rising flute scale which, Hopkins points out, is derived from a “rain” motif and thus signals restoration of a pastoral idyll while affirming the continuity of nature.

“Hirtengasang. Frohe, dankbare Gefühle nach dem Sturm” (“Shepherds’ song. Happy and thankful feelings after the storm”) – The final movement is perhaps the most heartfelt of all. It begins with an Alpine hunting call that evolves effortlessly into a meltingly gorgeous swaying tune that, in turn, launches a rondo which Lam depicts as the simplest in all of Beethoven’s works, and thus suitable to express the sentiments of unassuming shepherds. “Hirtengasang. Frohe, dankbare Gefühle nach dem Sturm” (“Shepherds’ song. Happy and thankful feelings after the storm”) – The final movement is perhaps the most heartfelt of all. It begins with an Alpine hunting call that evolves effortlessly into a meltingly gorgeous swaying tune that, in turn, launches a rondo which Lam depicts as the simplest in all of Beethoven’s works, and thus suitable to express the sentiments of unassuming shepherds.  Indeed, he considers the movement’s title to refer not to relief from the terrors of the storm, but rather gratitude for the life-giving refreshment of its nurturing rain. Although Beethoven retains the trombones from the preceding movement to underline the depth of feeling, he returns us to the same gentle peace and relaxation of the opening. The ending is inspired – no climax, but rather soft motivic repetitions that recall the brook scene, capped off by a final strong peremptory cadence, perhaps to remind us that after all this is just a piece of music and to abruptly and firmly return us to the artifice and pressures of our urban world. Indeed, he considers the movement’s title to refer not to relief from the terrors of the storm, but rather gratitude for the life-giving refreshment of its nurturing rain. Although Beethoven retains the trombones from the preceding movement to underline the depth of feeling, he returns us to the same gentle peace and relaxation of the opening. The ending is inspired – no climax, but rather soft motivic repetitions that recall the brook scene, capped off by a final strong peremptory cadence, perhaps to remind us that after all this is just a piece of music and to abruptly and firmly return us to the artifice and pressures of our urban world.

In describing the glories of this work commentaries tend to coalesce around notions of poetry, and with good reason – just as the best poetry manages to suggest ideas and feelings that transcend the specific connotations of the words, in the Pastoral Beethoven created a musical likeness in which impalpable, pensive sounds evoke a sense of awestruck wonder at the elements of nature – and in a way that no two listeners are apt to experience in the exact same way. In that light, Klaus Roy observes that there is a cogent reason why the German word for “composer” is “Tondichter” – a tone-poet. Tovey adds that Beethoven proved himself the master of language who could express the deepest feelings in his own terms, and that the themes develop in a natural way, just as thoughts and utterances gradually take shape, even though the overall structure is that of the classical symphony. More specifically, Lam cites the formation of the entire symphony from the basic relations of tonic, dominant and subdominant and marvels that “nowhere since the mid-17th century has the common chord been so glorified as here.” In describing the glories of this work commentaries tend to coalesce around notions of poetry, and with good reason – just as the best poetry manages to suggest ideas and feelings that transcend the specific connotations of the words, in the Pastoral Beethoven created a musical likeness in which impalpable, pensive sounds evoke a sense of awestruck wonder at the elements of nature – and in a way that no two listeners are apt to experience in the exact same way. In that light, Klaus Roy observes that there is a cogent reason why the German word for “composer” is “Tondichter” – a tone-poet. Tovey adds that Beethoven proved himself the master of language who could express the deepest feelings in his own terms, and that the themes develop in a natural way, just as thoughts and utterances gradually take shape, even though the overall structure is that of the classical symphony. More specifically, Lam cites the formation of the entire symphony from the basic relations of tonic, dominant and subdominant and marvels that “nowhere since the mid-17th century has the common chord been so glorified as here.”

The influence of this essentially modest work has been enormous, as it opened the gateways to two divergent stylistic approaches that would emerge with full force throughout the next century, and persist well into our own time. On the most sophisticated level, it served to validate the notion of music in which sheer feeling can override form, an approach that would peak in the hands of the late romantic and so-called Impressionist composers, who elevated tonal color and surges of atmospheric ardor to incomparable levels. Indeed, Berlioz hailed the Pastoral as the supreme example of the art of sound. More superficially, it also led to tone poems that, on the crudest level, sought popularity by illustrating specific extrinsic narratives rather than stimulating abstract thought from their intrinsic materials. But while earning the scorn of sophisticates, even those serve a valuable purpose – how many of us first became enthralled with serious music through The Sorcerer’s Apprentice or Til Eulenspiegel? After all, you have to crawl before you can run.

To modern ears, perhaps the most striking feature of the Pastoral’s splendor lies in its remarkable ability to draw us into its leisurely time-frame. As it patiently unfolds and we fall under its enchanting spell, we become blissfully oblivious to the normal demands of symphonic development and harmonic progress and gladly set aside the tense rhythms and hectic pace of our lives. Indeed, the composer Johann Friedrich Reichardt remarked of the premiere, with obvious exaggeration, that while “each number was a very long, thoroughly developed movement,” the symphony “went on even longer than an entire court concert of ours is allowed to last.” Not all early critics were enamored with this psychological phenomenon; thus the London Harmonium reported in June 1923: “Opinions are much divided concerning the merits of the Pastoral Symphony of Beethoven, though few venture to deny that it is much too long. To modern ears, perhaps the most striking feature of the Pastoral’s splendor lies in its remarkable ability to draw us into its leisurely time-frame. As it patiently unfolds and we fall under its enchanting spell, we become blissfully oblivious to the normal demands of symphonic development and harmonic progress and gladly set aside the tense rhythms and hectic pace of our lives. Indeed, the composer Johann Friedrich Reichardt remarked of the premiere, with obvious exaggeration, that while “each number was a very long, thoroughly developed movement,” the symphony “went on even longer than an entire court concert of ours is allowed to last.” Not all early critics were enamored with this psychological phenomenon; thus the London Harmonium reported in June 1923: “Opinions are much divided concerning the merits of the Pastoral Symphony of Beethoven, though few venture to deny that it is much too long.  The Andante [the Scene by the Brook] alone is upwards of a quarter of an hour in performance and, being a series of repetitions, might be subjected to abridgement without any violation of justice, either to the composer or to his hearers.” The Andante [the Scene by the Brook] alone is upwards of a quarter of an hour in performance and, being a series of repetitions, might be subjected to abridgement without any violation of justice, either to the composer or to his hearers.”

While such hostility to Beethoven’s genius seems unthinkable nowadays, part of the problem may have been a matter of tempo – if the second movement truly was played slowly enough to consume 15 minutes, it may indeed have been too long. In 1817 Beethoven published specific metronome directions, from which we can calculate the duration of each movement. For example, the second movement contains 139 measures of 12/8 time and specifies 50 dotted quarter notes (12.5 bars) to the minute, so dividing 139 bars by 12.5 bars per minute yields 11.12 minutes, or 11 minutes 7 seconds. Using this method, Beethoven’s timings are:

- I – 9:53, or 7:47 without the exposition repeat which nearly all early recordings omit

- II – 11:07

- III – 4:47, or 2:40 without the repeat

- IV – 3:52

- V – 8:48

Thus, with all repeats and adding the recording industry’s standard six-second pauses among the first three movements, Beethoven’s metronome markings yield a total timing of just about 38 2/3 minutes (34½ without repeats). As we will note, few conductors observe these tempos, and perhaps with good reason – even though the score has no indication of any variation, a rigid, unyielding pace sounds far too mechanical to achieve the desired aura of repose. Questions have also been raised as to whether the profoundly deaf composer’s mental image of his earlier work had remained sufficiently stable by 1817 to reliably represent the pacing he had envisioned when creating it.

Perhaps Reichart’s perception of extreme length was due in part to the trying circumstances of the premiere on December 22, 1808.

The Disney version – scenes from Fantasia

The Disney version – scenes from Fantasia |

Nowadays we can only lament that so many difficult and important new works were crammed into a four-hour marathon session that was more an endurance trial than a voyage of esthetic discovery and delight. (Schindler explains that Viennese theaters were available for concerts only four days each year – two days before Christmas and two days before Easter.) In an unheated, bitterly cold building a pick-up group (which Beethoven had managed to infuriate) essentially sight-read through not only the Pastoral but the world premieres of the Mass in C, the Fourth Piano Concerto, the Fifth Symphony, and the Choral Fantasia. (At least the Pastoral came first on the program.)

Whatever shred of dignity could have been salvaged from the premiere soon dissipated. Grove recounts that, notwithstanding the composer’s clear admonition, early performances included an 1829 London dramatization with “six French actors assisted by a numerous corps de ballet,” an 1863 Dusseldorf “illustration” with “scenery for the background and groups of reapers, peasants [and] a village parson,” and an 1864 Drury Lane performance “with pictorial and pantomimic illustrations” and the Misses Gunniss as the principal dancers. Yet, even they pale beside the vehicle through which most of the 20th century came to know the Pastoral – a 23-minute segment of the 1939 feature movie Fantasia in which the Disney animation team set a heavily cut but hyper-dramatic performance by Leopold Stokowski and the Philadelphia Orchestra (with exaggerated separation blaring through multi-channel "Fantasound" speakers) to mythological scenes of flying horses, preening topless nymphs and thunderbolt-hurling gods (but no singing birds!), all moving in strict time to the musical beats. (Lest any viewer be in doubt, in an introduction, narrator Deems Taylor assures us that the symphony tells a definite story.) Perhaps it was in anticipation of such perverse caricature that Tovey decried the “roaring cataract of nonsense descending upon this intensely musical work.” In any event, one can only shudder to imagine what Beethoven would have thought of it!

Let me qualify this survey with my usual caveat – there have been hundreds of recordings of the Pastoral, of which I’ve heard “only” a few dozen, so I make no pretense of being comprehensive. I’ve tried to include the most notable historical ones and a highly selective set of personal favorites intended to present a wide range of representative styles. The format for the headnotes is: Conductor, orchestra (year, original label, CD reissue [if any]; length). All are studio recordings unless otherwise indicated. Timings are the actual total, after which are noted missing first and/or third movement repeats (indicated as I and III); so for meaningful comparisons, simply add about 2½ minutes for each missing repeat. Let me qualify this survey with my usual caveat – there have been hundreds of recordings of the Pastoral, of which I’ve heard “only” a few dozen, so I make no pretense of being comprehensive. I’ve tried to include the most notable historical ones and a highly selective set of personal favorites intended to present a wide range of representative styles. The format for the headnotes is: Conductor, orchestra (year, original label, CD reissue [if any]; length). All are studio recordings unless otherwise indicated. Timings are the actual total, after which are noted missing first and/or third movement repeats (indicated as I and III); so for meaningful comparisons, simply add about 2½ minutes for each missing repeat.

- Hans Pfitzner: (1) Neues Symphonie-Orchester, Berlin (1923, Polydor 78s; 42:45 {I & III}); (2) Berlin State Opera Orchestra (1930, Polydor 78s, Naxos Historical CD; 42' {I & III})

Reportedly, the first Pastoral on record was released on five double-sided Odeon discs by the Odeon Streichorchester conducted by Eduard Künneke in early 1913, which would make it the second complete symphony ever recorded (following a 1911 Beethoven Fifth from Odeon led by either Künneke or Friedrich Kark, and thus ahead of the far more famous Nikisch/Berlin Philharmonic Fifth, often mistakenly cited as the first recording of a full symphony). I’ve never come across the Odeon Pastoral, but the same forces' extant Fifth suggests that it might have been swift, rigid and dimly recorded.  While the Fifth enjoyed many further recordings throughout the acoustic era, the Pastoral reemerged only in late 1923 with this rather disjointed reading by Hans Pfitzner. It gets off to an unpromising start with a first movement that is leisurely paced but mechanically played, each note warily separate at a constant volume and without a hint of inflection or feeling. The second movement is also relaxed, but with plastic phrasing and an especially mellow bassoon (in ironic contrast to its perfunctory role to come in the scherzo). The storm is fairly assertive, with rushed downward scales to heighten a feeling of tension and uncontrolled energy. The finale is meltingly lovely and radiates genuine warmth through the restricted sonic keyhole of the technology. Pfitzner became the first conductor to remake the Pastoral, again on Polydor but this time with the Berlin State Opera Orchestra as part of an integral set of the Beethoven symphonies intended to somewhat belatedly commemorate the centennial of the composer's death. (Pfitzner also led Symphonies 1, 3, 4 and 8 for the cycle; Kleiber led # 2, Strauss #s 5 and 7, and Fried # 9.) Mark Obert-Thorn has kindly clarified that this actually was Pfitzner's third Pastoral, as Pfitzner had already cut a remake with the State Opera Orchestra in late 1926 or early 1927 which confusingly bore the same catalog number (but different matrices). The movement timings of Pfitzner's Pastorals are virtually identical, but the opening of the remake is far more affecting and contemplative, the impact of its warmth arising in part from the genuine bass fidelity absent from the acoustic version. While the Fifth enjoyed many further recordings throughout the acoustic era, the Pastoral reemerged only in late 1923 with this rather disjointed reading by Hans Pfitzner. It gets off to an unpromising start with a first movement that is leisurely paced but mechanically played, each note warily separate at a constant volume and without a hint of inflection or feeling. The second movement is also relaxed, but with plastic phrasing and an especially mellow bassoon (in ironic contrast to its perfunctory role to come in the scherzo). The storm is fairly assertive, with rushed downward scales to heighten a feeling of tension and uncontrolled energy. The finale is meltingly lovely and radiates genuine warmth through the restricted sonic keyhole of the technology. Pfitzner became the first conductor to remake the Pastoral, again on Polydor but this time with the Berlin State Opera Orchestra as part of an integral set of the Beethoven symphonies intended to somewhat belatedly commemorate the centennial of the composer's death. (Pfitzner also led Symphonies 1, 3, 4 and 8 for the cycle; Kleiber led # 2, Strauss #s 5 and 7, and Fried # 9.) Mark Obert-Thorn has kindly clarified that this actually was Pfitzner's third Pastoral, as Pfitzner had already cut a remake with the State Opera Orchestra in late 1926 or early 1927 which confusingly bore the same catalog number (but different matrices). The movement timings of Pfitzner's Pastorals are virtually identical, but the opening of the remake is far more affecting and contemplative, the impact of its warmth arising in part from the genuine bass fidelity absent from the acoustic version.

- Frieder Weissmann, Berlin Opera House Orchestra (1924, Parlophone 78s; 39’ {I & III})

Weissmann’s acoustic set the following year exudes a breath of fresh air, beautifully played and enlivened throughout with constant subtle touches and an abundance of palpable enthusiasm – even the finale gains from emphatic downbeats to suggest the depth of the peasants’ gratitude. Bounding forward (the first movement timing is a full 2½ minutes faster than Pfitzner’s, although the “Scene by the Brook” is 1½ minutes slower) with nicely shaped phrasing and fine balances, the dynamics are carefully graded within a full range, even at the expense of dipping below the noise floor at several points (the quail song is completely inaudible, and the opening of the third movement nearly so). Surmounting the considerable technical challenges and requiring no apology for its age, it’s a fine, cohesive, thoroughly engrossing rendition that bursts with character and fully conveys the work’s spiritual essence.

- Franz Schalk, Vienna Philharmonic Orchestra (1928, HMV 78s, Lys CD; 39:25 {I})

Schalk is best remembered nowadays as the desecrator of his teacher Bruckner’s symphonies in an earnest if misguided attempt to conform them to audience expectations but, as Jean-Charles Hoffelé points out,  he strove for simplicity in his conducting as well – as a conservative antidote and successor to Mahler at the helm of the Vienna Philharmonic, he forbade vibrato, refrained from portamento, reduced expressive and ornamental glissandi to a bare minimum, and generally adhered to a single tempo for entire movements. While the steady first movement here exemplifies this simplicity of approach, the second is far different, its patient charm full of subtle tempo shifts; it even culminates with arhythmic birdcalls that impart a sense of nature in the raw more than conscious stylization. In one sense, it broke new ground – the first Pastoral on record to have included the third-movement repeat (but not the first). he strove for simplicity in his conducting as well – as a conservative antidote and successor to Mahler at the helm of the Vienna Philharmonic, he forbade vibrato, refrained from portamento, reduced expressive and ornamental glissandi to a bare minimum, and generally adhered to a single tempo for entire movements. While the steady first movement here exemplifies this simplicity of approach, the second is far different, its patient charm full of subtle tempo shifts; it even culminates with arhythmic birdcalls that impart a sense of nature in the raw more than conscious stylization. In one sense, it broke new ground – the first Pastoral on record to have included the third-movement repeat (but not the first).

- Felix Weingartner, Royal Philharmonic Orchestra (1927, Columbia 78s, Naxos Historical CD; 33:45 {I & III})

To Felix Weingartner goes another “first” – the first complete Beethoven symphony cycle on record under the baton of a single conductor (albeit spread out over a decade). Although he lived only until 1942, Weingartner recorded other Beethoven symphonies up to four times, but this is his only Pastoral. Perhaps not surprising in light of his extensive parallel career as a composer, he uses tempos in an expressive, creative and unusual way that stands apart from the two standard approaches of either adhering to steadfast pacing or slowing down for lyrical sections to emphasize transitions. In all but the last movement, he begins at a hurried pace and then imperceptibly decelerates as they progress to conclude at a normal rate. Thus the opening barely pauses for breath after the fermata and never slows down for the flowing second theme, yet manages to end with considerable breadth, as if to suggest that we enter the realm of nature imbued with the hectic pace of urban life, gradually become enthralled with its splendor, and invariably conform to its more relaxed tempo. The effect is even more pronounced in the second movement, which begins as a vigorous waltz, almost sounding in one, and ends with extremely deliberate bird songs, as if to dwell on these denizens of the natural world whose sounds perhaps were among the last ones the nearly deaf composer still could perceive. The scherzo is a bit different, beginning at Beethoven’s prescribed pace, but then slowing suddenly for the 2/4 peasant dance trio, as if to emphasize its coarseness. The impact of the slowing effect is perhaps most palpable in the storm, and serves to underline its increasing gravity. Yet, Weingartner varies his scheme in the finale, which he maintains at a sustained quick pace, as if to evoke both the enduring joy of a sojourn in the country and wishful thinking that basking in the bounty of nature could last unabated forever. The conclusion is abrupt, refusing to glide into a tranquil ending, as if to warn that this reverie really was just a momentary reprieve from the burdens of our lives, to which we now must return. Typical of Weingartner’s reputation for simplifying the personalized rhetoric that typified interpretation of his time, his technique is both plain and highly effective.

- Serge Koussevitzky, Boston Symphony Orchestra (1928, Victor 78s, Biddulph CD; 37:45 {I})

Koussevitzky approached music as a moral imperative and a mission to transmit this holy art to audiences. While he made some boldly impassioned recordings of Tchaikovsky, Sibelius and modern American works, many of his studio recordings tend to disappoint, seeming to reflect an aloof, patrician attitude at odds with the palpable elation and unabashed personalities we often expect from “golden age” conductors.   This, his first Beethoven recording, near the beginning of his 25-year tenure with the Boston Symphony, reflects his respectful regard of the older masters – it’s well-played and nicely balanced, yet somewhat drab, especially compared to the surging vitality of two Strauss waltzes he cut the very next day. Indeed, the third movement dance seems overly refined. Yet it does serve to emphasize Beethoven’s classical roots and isn’t totally bereft of personal touches. The first, second and final movements are steadfastly paced yet all end in vast deceleration, as if to suggest that we finally must succumb to nature’s leisure no matter how long esthetes might try to snub or resist it. He also brings the first movement development nearly to a halt after both of the lengthy 36-bar sequences of that incessantly repeated jaunty motif, as if to rekindle the joyous opening theme after getting sidetracked with an obsession. And by softening the second violins in the same section he manages to preserve Beethoven’s droll distinction between the divided violins as they swap long held notes and rapid figures; by distinguishing the two violin choirs through their textures, he restores the impact of the composer’s inventive orchestration and thus overcomes a difficult problem in a monaural recording, in which the two violin parts invariably merge together. This, his first Beethoven recording, near the beginning of his 25-year tenure with the Boston Symphony, reflects his respectful regard of the older masters – it’s well-played and nicely balanced, yet somewhat drab, especially compared to the surging vitality of two Strauss waltzes he cut the very next day. Indeed, the third movement dance seems overly refined. Yet it does serve to emphasize Beethoven’s classical roots and isn’t totally bereft of personal touches. The first, second and final movements are steadfastly paced yet all end in vast deceleration, as if to suggest that we finally must succumb to nature’s leisure no matter how long esthetes might try to snub or resist it. He also brings the first movement development nearly to a halt after both of the lengthy 36-bar sequences of that incessantly repeated jaunty motif, as if to rekindle the joyous opening theme after getting sidetracked with an obsession. And by softening the second violins in the same section he manages to preserve Beethoven’s droll distinction between the divided violins as they swap long held notes and rapid figures; by distinguishing the two violin choirs through their textures, he restores the impact of the composer’s inventive orchestration and thus overcomes a difficult problem in a monaural recording, in which the two violin parts invariably merge together.

- Max von Schillings, Berlin State Opera Orchestra (1929, Parlophon 78s, Pristine Audio download; 43’ {I})

It’s truly frustrating how often luminous art and monstrous politics clash, and nowhere more cruelly than here. A virulent anti-semite who mercilessly purged Jews during his fortunately brief tenure as president of the Prussian Academy of Arts, von Schillings recorded exquisitely sensitive readings of the German repertoire, including this altogether lovely Pastoral. Ideally poised between tender repose and purposeful evolution, it shares his pupil Furtwängler’s intuitive ability to invest each phrase with significant inflection that prevents his relaxed pacing from ever threatening to lapse into tedium. Indeed, at 14:38 his scene by the brook is not only one of its most leisurely, but thoroughly engaging and beneficent, recordings and his finale radiates great warmth. Perhaps it’s part of the same perplexing moral blinders that enabled Nazi physicians to perform sadistic medical experiments and death camp commandants to grow lovely flower gardens for their adoring wives and children.

- Willem Mengelberg, Concertgebouw Orchestra, Amsterdam (1937, Telefunken 78s, Teldec CD; 36’ {I}); (live, 1940, Music & Arts CD; 38’ {I})

Most conductors of the Pastoral lead us through a countryside that welcomes us with familiarity and lulls us into a blissful sense of habitual comfort.  Mengelberg, though, constantly draws our attention to its evolving features and lets us see it all with new eyes and appreciation of its burgeoning vitality. By the time of his studio recording, Mengelberg already had been the permanent conductor of the Concertgebouw for an astounding 42 years, and so it’s no surprise that the ensemble plays for him with extraordinary finesse and polish – and repeats the feat down to the smallest details during their aptly famed April 1940 Beethoven cycle. As an “old school” conductor who confidently asserted his own interpretive views, Mengelberg’s readings burst with constantly fascinating emphases, balances, ornaments, dynamics, phrasing – and a fair amount of tampering with the score itself; thus, in the storm he blasts a trumpet note marked pp (bars 60-61) and adds a powerful tympani roll leading to the first outburst (bars 19-20). While many recordings’ creativity seems depleted after the storm, Mengelberg saves his most striking touches for the finale – not only does he constantly cut short the fifth note of the theme of the finale, but finds a subtly different tempo for each of its entrances, as if to exemplify that within the basic continuity of a simple country life lies constant variety and renewal. But while this may sound like a misguided ego-trip that cruelly distorts the composer’s conception, it all works beautifully and serves to refocus our attention on a work we thought we knew well and tend to take for granted. Mengelberg, though, constantly draws our attention to its evolving features and lets us see it all with new eyes and appreciation of its burgeoning vitality. By the time of his studio recording, Mengelberg already had been the permanent conductor of the Concertgebouw for an astounding 42 years, and so it’s no surprise that the ensemble plays for him with extraordinary finesse and polish – and repeats the feat down to the smallest details during their aptly famed April 1940 Beethoven cycle. As an “old school” conductor who confidently asserted his own interpretive views, Mengelberg’s readings burst with constantly fascinating emphases, balances, ornaments, dynamics, phrasing – and a fair amount of tampering with the score itself; thus, in the storm he blasts a trumpet note marked pp (bars 60-61) and adds a powerful tympani roll leading to the first outburst (bars 19-20). While many recordings’ creativity seems depleted after the storm, Mengelberg saves his most striking touches for the finale – not only does he constantly cut short the fifth note of the theme of the finale, but finds a subtly different tempo for each of its entrances, as if to exemplify that within the basic continuity of a simple country life lies constant variety and renewal. But while this may sound like a misguided ego-trip that cruelly distorts the composer’s conception, it all works beautifully and serves to refocus our attention on a work we thought we knew well and tend to take for granted.

- Arturo Toscanini – (1) BBC Symphony Orchestra (1937, EMI 78s, Biddulph CD, 38’ {I}); (2) NBC Symphony Orchestra (live 1939, Relief or Music & Arts CD, 40’ {I}); (3) NBC Symphony Orchestra (1952, RCA LP, BMG CD, 41’ {I})

Conventional wisdom is that Toscanini revolutionized conducting (and music performance generally).  In lieu of a partnership between composer and artist that encouraged interpretive input and had become accepted in the late 19th century, Toscanini sought to objectively and scrupulously present the composer’s intention, as evidenced by the score. As we have noted, long before Toscanini cut his first recording of the Pastoral, others had already documented his approach on disc. Yet, by 1937 he had been conducting for over a half-century and so his influence clearly predated the advent of music recording itself, much less his BBC sessions. Exalted among the greatest recordings ever made, his BBC Pastoral remains a superb example of Toscanini’s art before it began to calcify, at least in the studio – fundamentally detached, but with just enough elasticity and warmth to avoid a sense of mechanical rigidity. Both playing and recording are excellent, although the winds are a bit loud and tympani are nowhere to be heard during the storm. Toscanini’s only other official release of the Pastoral was a 1952 NBC studio recording, essentially the same reading with a marginally slower first movement but redeemed by a knockout of a storm with drums that really tear the sonic fabric. (About those drums – while Toscanini claimed to derive his inspiration directly from the score, he was no purist; as Harris Goldsmith points out, in all but his first NBC concert of the Pastoral he reinforced the tympani in the storm and added concluding turns to the violin trills in the scene by the brook.) Also compelling are several NBC broadcast concerts. The earliest in January 1937 is understandably just a bit tentative, as it was only Toscanini’s third outing with his brand new orchestra, and seems to serve as a transition between the smooth refinement of the BBC and the sharp precision, tighter articulation, broader dynamics and overall urgency of the NBC. The last, from March 1954 (the third to last concert of his career), provides an extra kick of live energy absent in the studio. Best of all is a concert given as part of a 1939 NBC Beethoven cycle, with nearly identical movement timings to his other NBC concert versions, but enhanced with tension and swaggering confidence reflecting the full maturity of the rapport that already had developed between Toscanini and his orchestra. Toscanini clearly esteemed the Pastoral – he led it in more NBC concerts than any other Beethoven symphony – and each performance succeeds in eschewing personality (and he had a huge one!) to focus attention on the work itself. In lieu of a partnership between composer and artist that encouraged interpretive input and had become accepted in the late 19th century, Toscanini sought to objectively and scrupulously present the composer’s intention, as evidenced by the score. As we have noted, long before Toscanini cut his first recording of the Pastoral, others had already documented his approach on disc. Yet, by 1937 he had been conducting for over a half-century and so his influence clearly predated the advent of music recording itself, much less his BBC sessions. Exalted among the greatest recordings ever made, his BBC Pastoral remains a superb example of Toscanini’s art before it began to calcify, at least in the studio – fundamentally detached, but with just enough elasticity and warmth to avoid a sense of mechanical rigidity. Both playing and recording are excellent, although the winds are a bit loud and tympani are nowhere to be heard during the storm. Toscanini’s only other official release of the Pastoral was a 1952 NBC studio recording, essentially the same reading with a marginally slower first movement but redeemed by a knockout of a storm with drums that really tear the sonic fabric. (About those drums – while Toscanini claimed to derive his inspiration directly from the score, he was no purist; as Harris Goldsmith points out, in all but his first NBC concert of the Pastoral he reinforced the tympani in the storm and added concluding turns to the violin trills in the scene by the brook.) Also compelling are several NBC broadcast concerts. The earliest in January 1937 is understandably just a bit tentative, as it was only Toscanini’s third outing with his brand new orchestra, and seems to serve as a transition between the smooth refinement of the BBC and the sharp precision, tighter articulation, broader dynamics and overall urgency of the NBC. The last, from March 1954 (the third to last concert of his career), provides an extra kick of live energy absent in the studio. Best of all is a concert given as part of a 1939 NBC Beethoven cycle, with nearly identical movement timings to his other NBC concert versions, but enhanced with tension and swaggering confidence reflecting the full maturity of the rapport that already had developed between Toscanini and his orchestra. Toscanini clearly esteemed the Pastoral – he led it in more NBC concerts than any other Beethoven symphony – and each performance succeeds in eschewing personality (and he had a huge one!) to focus attention on the work itself.

- Wilhelm Furtwängler, Berlin Philharmonic (1) (live, 1944, Music & Arts CD, 43½’{I}), (2) (live, 1947, Music & Arts CD, 43’{I}), (3) (live, 1954, Virtuoso CD, 43’{I})

Furtwängler’s mystical groping for intellectual and metaphysical insight, allied with his unbridled emotion and creative improvisation, were diametrically opposed to the objectivity of Toscanini, whom Furtwängler disdained as a mere “stick waver.” While Toscanini may have illuminated the Pastoral with the brilliant Mediterranean sun, Furtwängler steeped his readings in German mysticism. His several concert recordings of the Pastoral with the Berlin Philharmonic are remarkably similar in global shape, gesture and timing, but the prize among them arose on May 25, 1947, when he used this work, and its companion Fifth Symphony, as the vehicle through which he resumed his career and rejoined the musical world after having escaped to Switzerland in February 1945 and then awaiting exoneration by the Allied command. (Click here for more information.) Into both works he poured his own emotional voyage. The Fifth Symphony progresses from a grim opening to an ecstatic explosion of triumph, but the Pastoral is subtler. His 1944 concert may reflect a wistful yearning for an elusive peace, and his 1954 concert may suggest an autumnal remembrance of a weary master, but this, after 27 months of forced inactivity, is a heartfelt prayer of thanks for deliverance. In the leisurely first movement – 11½ minutes without the repeat – vast swells of sound well up from barely audible whispers and end on shimmering, lingering chords that lead to a second movement of unspeakable tenderness that continues the process of swinging between soft reverie and earnest accelerated urgency. The third movement is eerie, hinting of hidden things, deep and elemental, which emerge in the storm, fueled not only by tympani of Toscaninian intensity but by a screaming, terrorized piccolo, which, in turn, cedes to a finale of sheer, unbridled joy that sweeps all before it to conclude on a note of hope for all humanity. None of this has much to do with nature. Rather, consistent with his genius, Furtwängler internalized the score and produced a deeply personal interpretation of independent validity that touches the creative soul within each of us. (Furtwängler’s best-known rendition, a 1952 EMI studio recording with the Vienna Philharmonic, is similar in its architecture but less inspired, and a 1954 Lucerne concert is slower and a bit tired.) allied with his unbridled emotion and creative improvisation, were diametrically opposed to the objectivity of Toscanini, whom Furtwängler disdained as a mere “stick waver.” While Toscanini may have illuminated the Pastoral with the brilliant Mediterranean sun, Furtwängler steeped his readings in German mysticism. His several concert recordings of the Pastoral with the Berlin Philharmonic are remarkably similar in global shape, gesture and timing, but the prize among them arose on May 25, 1947, when he used this work, and its companion Fifth Symphony, as the vehicle through which he resumed his career and rejoined the musical world after having escaped to Switzerland in February 1945 and then awaiting exoneration by the Allied command. (Click here for more information.) Into both works he poured his own emotional voyage. The Fifth Symphony progresses from a grim opening to an ecstatic explosion of triumph, but the Pastoral is subtler. His 1944 concert may reflect a wistful yearning for an elusive peace, and his 1954 concert may suggest an autumnal remembrance of a weary master, but this, after 27 months of forced inactivity, is a heartfelt prayer of thanks for deliverance. In the leisurely first movement – 11½ minutes without the repeat – vast swells of sound well up from barely audible whispers and end on shimmering, lingering chords that lead to a second movement of unspeakable tenderness that continues the process of swinging between soft reverie and earnest accelerated urgency. The third movement is eerie, hinting of hidden things, deep and elemental, which emerge in the storm, fueled not only by tympani of Toscaninian intensity but by a screaming, terrorized piccolo, which, in turn, cedes to a finale of sheer, unbridled joy that sweeps all before it to conclude on a note of hope for all humanity. None of this has much to do with nature. Rather, consistent with his genius, Furtwängler internalized the score and produced a deeply personal interpretation of independent validity that touches the creative soul within each of us. (Furtwängler’s best-known rendition, a 1952 EMI studio recording with the Vienna Philharmonic, is similar in its architecture but less inspired, and a 1954 Lucerne concert is slower and a bit tired.)

- Hermann Abendroth, Leipzig Radio Symphony Orchestra (live, 1949, Arlecchino CD, 42’ {I})

Abendroth routinely is seen only dimly in the vast shadow of Furtwängler, but he, too, was one of the greatest exemplars of the German Romantic tradition. Although by no means identical, their Pastorals are much in the same vein, with similar timings (despite Abendroth’s faster arrival in the country), overarching architectures, deeply-felt structural emphases, carefully-punctuated phrases, exquisitely tender scenes by the brook, vertiginous peasant dances that collapse into exhaustion, slashing storms subsiding into tender embraces of the earth, and warmly flowing expressions of thanksgiving. That said, the problem I find with highly individual accounts is that with repeated hearings the initial delight soon fades into mannerism. Much of my fascination with Abendroth is that he provides a useful, if marginally less impressive, alternative to the Furtwängler concerts and thus expands our exposure to the ethos of their era. At the same time, the fundamental similarity of their work ensures that neither can be written off as a mere aberration; rather, each validates the other, and together they represent and preserve an important interpretive tradition in musical history.

- Bruno Walter – (1) Vienna Philharmonic (1936, Gramophone 78s, Lys CD, 39’ {I}); (2) Philadelphia Orchestra (1946, Columbia 78s and LP, 38½’ {I}); (3) Columbia Symphony Orchestra (1958, Columbia LP, Sony CD, 41’ {I})

As with Toscanini, Walter’s career can be heard in several phases, three of which are documented by his recordings of the Pastoral. Prior to the Anschluss he was based in Europe and exemplified the Viennese tradition with rich, sturdy readings of the standard German repertoire, including much Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven. His 1936 Vienna Philharmonic Pastoral falls solidly in that vein – refined, plush and secure. Next, following emigration to the US in 1939, he underwent a radical shift of temperament and, in a striking, if delayed, manifestation of the spirit of his mentor Mahler, produced white-hot readings of opera and symphonic work. A Pastoral along those lines could have been uniquely spellbinding but, alas, by the time he cut a 1946 Pastoral with the Philadelphia Orchestra he already had reverted to his former balanced approach. Even so, it’s a fascinating balance of the Viennese roots he had left behind and the crisp assertiveness of his newly adopted American home. His final phase followed a 1957 heart attack at age 81, when he embarked in Los Angeles with the “Columbia Symphony Orchestra” on an extensive series of genial stereo recordings infused with extraordinary warmth. While many consider them to be among the best Bruckner and Mahler on record, I find their “kinder, gentler” approach somewhat impotent in such works, as they sidestep the inherent weight and drama. Yet the pervasive warmth seems ideally suited to the Pastoral, and his 1958 Columbia reading works quite well, underlining the composer’s softer side that nature clearly inspired, and its bright recording and considerable detail suggest an enduringly optimistic blend of delight and enthusiasm, only barely disrupted by a light summer shower. Walter clearly loved this work, as it was the first (and only) Beethoven symphony he waxed in Europe and the only one he recorded three times. His tender affection is evident in each of them. three of which are documented by his recordings of the Pastoral. Prior to the Anschluss he was based in Europe and exemplified the Viennese tradition with rich, sturdy readings of the standard German repertoire, including much Haydn, Mozart and Beethoven. His 1936 Vienna Philharmonic Pastoral falls solidly in that vein – refined, plush and secure. Next, following emigration to the US in 1939, he underwent a radical shift of temperament and, in a striking, if delayed, manifestation of the spirit of his mentor Mahler, produced white-hot readings of opera and symphonic work. A Pastoral along those lines could have been uniquely spellbinding but, alas, by the time he cut a 1946 Pastoral with the Philadelphia Orchestra he already had reverted to his former balanced approach. Even so, it’s a fascinating balance of the Viennese roots he had left behind and the crisp assertiveness of his newly adopted American home. His final phase followed a 1957 heart attack at age 81, when he embarked in Los Angeles with the “Columbia Symphony Orchestra” on an extensive series of genial stereo recordings infused with extraordinary warmth. While many consider them to be among the best Bruckner and Mahler on record, I find their “kinder, gentler” approach somewhat impotent in such works, as they sidestep the inherent weight and drama. Yet the pervasive warmth seems ideally suited to the Pastoral, and his 1958 Columbia reading works quite well, underlining the composer’s softer side that nature clearly inspired, and its bright recording and considerable detail suggest an enduringly optimistic blend of delight and enthusiasm, only barely disrupted by a light summer shower. Walter clearly loved this work, as it was the first (and only) Beethoven symphony he waxed in Europe and the only one he recorded three times. His tender affection is evident in each of them.

- Hermann Scherchen – (1) Vienna State Opera Orchestra (1958, Westminster LP and CD; 34’ {I & III}); (2) Italian Swiss Radio Orchestra (live 1965, private download; 34’ {I & III})

- Paul Paray - (1) Colonne Orchestra (1934, Columbia 78s; 36' {I & III}); (2) Detroit Symphony Orchestra (1954, Mercury LP; 35½’ {I})