|

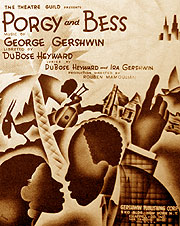

George Gershwin's Porgy and Bess bears the odd distinction of being both the most acclaimed and vilified of all American operas.

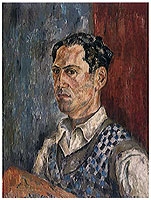

Gershwin – Self-portrait |

![]()

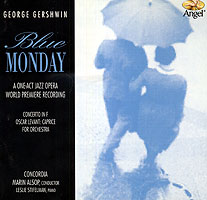

Gershwin had written the scores for the 1920, 1921 and 1922 annual editions of the popular George White's Scandals Broadway revue (and he would provide the next two years' as well). To open the second act of the 1922 show, in a mere five days he and librettist Buddy De Sylva whipped up Blue Monday, a 25-minute "colored Harlem tragedy enacted in the operatic style" by white singers in blackface. Set in a basement nightclub, it treads a thin line between emulation and parody. A lively instrumental introduction tosses lots of thematic ideas together and then leads into an explanatory recitative. After the catchy title blues sung by a worker as he sweeps the floor, Vi, the sweetheart of Joe, a gambler, resists the advances of Tom, a swaggering entertainer. Joe explains to Mike, the proprietor, that with his winnings he plans to visit his mother, whom he reveres in a mawkish ballad. A crowd enters to lively dance music.  Ashamed of his sentiment, Joe refuses to let Vi see a telegram from his mother. Tom claims it is from another woman. Vi shoots Joe, she learns the truth and collapses, and Joe reprises his "mammy song" as he dies. After a single performance, White pulled it as too somber and depressing for his show. It fared little better as a 1925 concert revival (with no sets and minimal props) retitled 135th Street. New York critical opinion was polarized. The World slammed it as "the most dismal, stupid and incredible black-face sketch that has probably ever been perpetrated," while the Sun dismissed the music as "an unimpressive accompaniment for an old hokum vaudeville skit." Yet one prophetic reviewer, identified only as "W.S.," hailed it as "the first real American opera. … In it we see the first gleam of a new American musical art." Another predicted: "This opera will be imitated in a hundred years." While prescient, his timing was off by nearly nine decades.

Ashamed of his sentiment, Joe refuses to let Vi see a telegram from his mother. Tom claims it is from another woman. Vi shoots Joe, she learns the truth and collapses, and Joe reprises his "mammy song" as he dies. After a single performance, White pulled it as too somber and depressing for his show. It fared little better as a 1925 concert revival (with no sets and minimal props) retitled 135th Street. New York critical opinion was polarized. The World slammed it as "the most dismal, stupid and incredible black-face sketch that has probably ever been perpetrated," while the Sun dismissed the music as "an unimpressive accompaniment for an old hokum vaudeville skit." Yet one prophetic reviewer, identified only as "W.S.," hailed it as "the first real American opera. … In it we see the first gleam of a new American musical art." Another predicted: "This opera will be imitated in a hundred years." While prescient, his timing was off by nearly nine decades.

While conceding the absurd story and inept drama, later critics have been intrigued by the music and view it as a herald of far greater things to come. Gershwin himself later called it a "laboratory work." As early as 1926, Henry O. Osgood found the score "varied, effective, distinctly dramatic and cleverly done" and averred that "Gershwin demonstrated the possibilities of jazz as legitimate operatic material when handled with imagination." Olin Downes called it "20 minutes of as vivid a 'grand opera' as has yet been provided from native and local materials by an American composer." In retrospect, while the melodies are mostly forgettable, we can hear the same harmonic excursions that typify Gershwin's songs and a nascent effort to depict drama and character in instrumental terms. As for its now-embarrassing blackface, Edward Jablonski finds its "stereotypical racism no worse than the standard treatment of the Negro by white writers and the common attitude of the time."

![]()

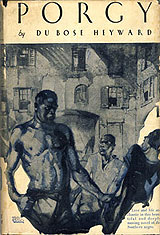

The next leap toward Porgy and Bess came in 1926 when Gershwin became enthralled with Porgy, a new novel by DuBose Heyward.

The title character was based on Samuel Smalls, a well-known disabled Charleston beggar who travelled in a soap-box cart pulled by a smelly goat, and who disappeared after trying to shoot a woman.  Heyward claimed that his novel was an attempt to imagine "Goat Sammy's" interior life with which he perhaps could identify – a scion of a destitute aristocratic family, his arms weakened by polio, Heyward worked on the waterfront as a cotton-checker where he mingled with black dock workers and fishermen. (Kendra Hamilton deflates any romantic vision by noting that neighbors recalled "Goat Cart Sam" as a mean drunkard who scared kids and beat girlfriends with his goat whip. The novel's depiction was far more benevolent.) Heyward's setting was "Cabbage Row," a once-elegant antebellum home in his neighborhood two blocks from the water that had become a rundown tenement inhabited by black servants and laborers.

Heyward claimed that his novel was an attempt to imagine "Goat Sammy's" interior life with which he perhaps could identify – a scion of a destitute aristocratic family, his arms weakened by polio, Heyward worked on the waterfront as a cotton-checker where he mingled with black dock workers and fishermen. (Kendra Hamilton deflates any romantic vision by noting that neighbors recalled "Goat Cart Sam" as a mean drunkard who scared kids and beat girlfriends with his goat whip. The novel's depiction was far more benevolent.) Heyward's setting was "Cabbage Row," a once-elegant antebellum home in his neighborhood two blocks from the water that had become a rundown tenement inhabited by black servants and laborers.

It's rather hard to appreciate the novel from a modern perspective. Ellen Noonan calls it sentimental and paternalistic, reflecting an Old Southern white view of race relations entrenched in the status quo and implicitly arguing for the futility of advancement or escape – indeed, nearly all the residents are resigned to poverty, gamble away what little money they earn, and readily bow to constant harassment by whites – and the only "professionals" among them are a crooked lawyer and a dope pusher. But social perspective aside, the most grating aspect for modern readers is the astoundingly prevalent use of the "n-word," not only occasionally by condescending whites but far more often self-referentially among the blacks themselves. Heyward considered it authentic rather than offensive, stating that in Charleston "we heard it 50 times a day." (The impact is slightly mitigated by use of the term "negro" [lower-case] throughout the passages of narration.) Indeed, according to Joan Peyser, Gershwin referred to 135th Street as his "N----- opera" and apparently routinely used the word, now indisputably an insult, as intending no disrespect. Otherwise, the dialect is fascinating, based on Gullah, an amalgam of English, African and creole patois spoken by descendants of slaves living along the South Carolina coast. However, only a single authentic Gullah word is used ("Buckra" = white man), resulting in an invented hybrid that sticks with English vocabulary but leaves the distinctive Gullah grammar and pronunciation relatively intact. That, in turn, draws an extreme and somewhat awkward disconnect between the omniscient, cultured observer of the narrative and the earthy humor and folk wisdom of the residents' speech. Consider, for example:

"He sho' gots de kin' wut goin' gib um hell," Serena commented cynically.Generally, the gracious, poetic tone of the narrative seems at odds with the directness of both the plot and its people. Consider the philosophical ambling of the opening:

"Dat de t'ing!" said Peter, a note of admiration in his voice, "She sho ain't axin' no visit offen none of she heighbor."

"Wut mek yuh ain't mobe intuh de shade?" a neighbor asked curiously.

Porgy lived in the Golden Age. Not the Golden Age of a remote and legendary past; nor yet the chimerical era treasured by every man past middle life, that never existed except in the heart of youth; but an age when men, not yet old, were boys in an ancient, beautiful city that time had forgotten before it destroyed.

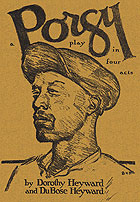

![]() Gershwin immediately proposed an operatic treatment, but Heyward's wife Dorothy was already converting Porgy into a play. In retrospect, that was opportune, as Gershwin conceded that he needed more study before tackling an opera.

Gershwin immediately proposed an operatic treatment, but Heyward's wife Dorothy was already converting Porgy into a play. In retrospect, that was opportune, as Gershwin conceded that he needed more study before tackling an opera.  In the meantime, the play repeated the success of the novel, opening on Broadway in October 1927 with an all-black cast and going on a national tour after a year in New York. While the basic plot and characters remained largely intact, the transition between media required structural changes. Notably, the dialog had to be expanded and characters enriched to subsume the background and observations that had been conveyed by the novel's detached narration. Thus the two villains were humanized to near-operatic complexity – the brutish Crown rushes out into a hurricane to effect a rescue as all the other men cower, and the shady dope peddler Sportin' Life is full of witty home-brewed wisdom, as when he explains a benefit of monogamy: "When a 'oman gots jus' one man, mebby she gots um for keep. But when she gots two mens – dere's might apt to be carvin! – An' de cops takes de leabin's." While the novel alluded to spirituals being sung, the play actually integrated a dozen, especially into the scenes of mourning, and provided their full texts (including "Ain't It Hard to be a N-----" which had already appeared in the novel but here apparently was considered so catchy it was sung twice). Alas, the n-word was as prevalent as ever – all the more curious in light of the racial background of the cast. Worse, Noonan points out that the play was hailed and widely accepted as an authentic depiction of black Southern life.

In the meantime, the play repeated the success of the novel, opening on Broadway in October 1927 with an all-black cast and going on a national tour after a year in New York. While the basic plot and characters remained largely intact, the transition between media required structural changes. Notably, the dialog had to be expanded and characters enriched to subsume the background and observations that had been conveyed by the novel's detached narration. Thus the two villains were humanized to near-operatic complexity – the brutish Crown rushes out into a hurricane to effect a rescue as all the other men cower, and the shady dope peddler Sportin' Life is full of witty home-brewed wisdom, as when he explains a benefit of monogamy: "When a 'oman gots jus' one man, mebby she gots um for keep. But when she gots two mens – dere's might apt to be carvin! – An' de cops takes de leabin's." While the novel alluded to spirituals being sung, the play actually integrated a dozen, especially into the scenes of mourning, and provided their full texts (including "Ain't It Hard to be a N-----" which had already appeared in the novel but here apparently was considered so catchy it was sung twice). Alas, the n-word was as prevalent as ever – all the more curious in light of the racial background of the cast. Worse, Noonan points out that the play was hailed and widely accepted as an authentic depiction of black Southern life.

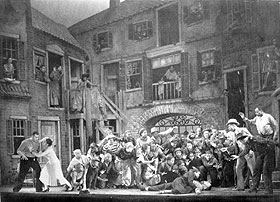

Stage directions were exhaustively detailed. As catalogued by Joseph Horowitz, the director, Rouben Mamoulian, was obsessed with dramatic blocking, lighting and rhythm, adding a sonic tapestry of shuffles, grunts, moans, finger-snaps, shutters banging, rain and other sound effects that reached its apex in a "noise symphony" that opened the final scene with a precisely-patterned depiction of expanding daybreak activity as the community comes to life (largely replicating the ingenious three-minute opening sequence of Mamoulian's 1932 movie Love Me Tonight in which Paris awakens). The play originally was to have opened in a bold linguistic encounter with authentic Gullah banter that slowly evolved into familiar, if strongly accented, language, but apparently it confused audiences and was dropped.

![]() Gershwin's rocketing career was all-consuming, yet his enthusiasm for Porgy persisted, although it was nearly derailed in 1932 by Al Jolson, who wanted to commission a musical version by Jerome Kern and Oscar Hammerstein, whose hugely successful 1927 Showboat had paved the way for black characters on Broadway, albeit only in supporting roles. Jolson was to star in blackface. The Heywards were sorely tempted by the financial success that would be ensured by "The World's Greatest Entertainer," and Gershwin assured them that it would not impair his opera, but the plan never materialized.

Gershwin's rocketing career was all-consuming, yet his enthusiasm for Porgy persisted, although it was nearly derailed in 1932 by Al Jolson, who wanted to commission a musical version by Jerome Kern and Oscar Hammerstein, whose hugely successful 1927 Showboat had paved the way for black characters on Broadway, albeit only in supporting roles. Jolson was to star in blackface. The Heywards were sorely tempted by the financial success that would be ensured by "The World's Greatest Entertainer," and Gershwin assured them that it would not impair his opera, but the plan never materialized.

DuBose and Dorothy Heyward |

In November 1933 Heyward began preparing a libretto by paring the play and anglicizing much of the dialog, even while preserving the authentic phrasing and rhythms, which Gershwin would seek to emulate in his music. The next summer Gershwin turned his full attention to the opera project. He began by spending five weeks in a screened shack (with no water or phone but lots of mosquitoes and an upright piano) on Folly Island, a South Carolina barrier island ten miles from Charleston adjacent to a large Gullah population. Gershwin was enthralled, attending prayer meetings, absorbing spirituals and African rhythms, joining in "shouting" (a Gullah practice of beating out rhythmic patterns with hands and feet to accompany spirituals) – and entertaining the locals with his irrepressible piano playing. Heyward viewed Folly Island as a laboratory as well as an inexhaustible source of folk material but came to call Gershwin's stay "more like a homecoming than an exploration." Undoubtedly impressed by the sense of community to which the social fabric adhered, Gershwin would devote particular attention and characterization to the ensemble singing in his opera. Even so, Gershwin could not compose in the country, as he was too distracted by the natural sounds, and returned to New York, while Heyward remained in Charleston. Their collaboration was mostly by mail.

George Gershwin, DuBose Haywood and Ira Gershwin |

Gershwin felt that the Gullahs were an ideal subject, "because they express themselves not only by the spoken word but quite naturally by song and dance." Others have suggested a deeper basis for Gershwin's empathy – that as a Jew he, too, was isolated from mainstream society (and indeed many critics of the time linked Jewish entrée into popular music to the "degeneracy" of black jazz, which they blamed for a consequent spread of moral decay that threatened the purity of European-derived American culture). Wilfred Mellers even goes so far as to suggest that Gershwin suffered from such spiritual isolation as to become an "emotional cripple from nervous maladjustment" and thus able to identify with the Gullahs and perhaps even Porgy.

At some point the creative team was joined by Gershwin's lyricist brother Ira, a close collaborator with the composer, whose feeling for sophisticated rhymes complemented Heyward's poetic sensitivity for native resources. Thus, according to the copyrights, Ira crafted the words to "It Ain't Necessarily So" ("De t'ings dat yo' li'ble / to read in de Bible / It ain't necessarily so"), they shared credit for "I Got Plenty o' Nuttin'" ("De folks wid plenty o' plenty / got a lock on de door, / 'fraid somebody's a-goin' to rob 'em / while dey's out a-makin' more") and Heyward wrote "Summertime," masterfully melding lines from the play (Crown: "I waitin' here 'til de cotton begin comin' in. Den libbin' 'll be easy.") with a traditional lullabye ("Hush, little baby, don' yo' cry, mudder and fadder born to die.") into the universal prayer of every parent to comfort and guard a child, but here the hope for its brighter future is grounded by poverty that turns earnest hope into illusive fantasy:

Summertime an' the livin' is easy,That's not to suggest that all the lyrics are inspired – consider the awkward phrasing, patronizing text and strained rhymes of the picnic chorale: "Happy feelin' in my bones astealin' / No concealin' dat it's picnic day. / Sho's is dandy, got the licker handy. / Me an' Mandy, we is on de way … ."

Fish are jumpin' an' the cotton is high.

Oh, your daddy's rich and your ma is good lookin',

So hush, little baby, don' yo' cry.

One of these mornin's you goin' to rise up singin',

Then you'll spread yo' wings an' you'll take the sky.

But 'til that mornin', there's a-nothin' can harm you

With Daddy an' Mammy standin' by.

![]() As crafted by Gershwin and Heyward, Porgy and Bess comprised three acts and nine scenes using three sets. The musical highlights are given in parentheses:

As crafted by Gershwin and Heyward, Porgy and Bess comprised three acts and nine scenes using three sets. The musical highlights are given in parentheses:

![]()

Scene 1 – On a summer evening on Catfish Row, Jasbo Brown plays some blues on an old upright piano as couples hum and sway.

Robbins's death – Act I, scene 1 (original production) |

Scene 2 – In Serena's room, the community mourns ("Gone, Gone, Gone") and collects money in a saucer for the funeral ("Overflow, overflow"). Serena mourns her husband ("My Man's Gone Now"). The wake concludes with an upbeat spiritual ("Leavin' For the Promise' Lan'").

![]()

Scene 1 – A month later, the fishermen prepare to embark ("It Takes a Long Pull to Get There"). Porgy is carefree ("I Got Plenty of Nothin'"). The matronly cook-shop keeper Maria scolds Sportin' Life for selling dope ("I Hates Yo' Struttin' Style"). Porgy pays a crooked lawyer for a divorce for Bess but fears that a buzzard will bring bad luck ("The Buzzard Song"). After the others leave for a picnic, Porgy and Bess declare their love ("Bess, You Is My Woman Now").

Scene 2 – On Kittiwah Island, as the picnic winds down Sportin' Life sings of his religious skepticism ("It Ain't Necessarily So"). Bess lingers and is confronted by Crown who has been hiding out in wait for her. At first she resists him ("What You Want Wid' Bess?") but soon gives in to his seduction.

Scene 3 – Back at Catfish Row a week later, Bess is delirious and babbles about Crown. Serena prays for her ("Oh, Doctor Jesus"). Merchants hawk their wares ("Oh Dey's So Fresh an' Fine"). Porgy vows to protect Bess from Crown ("I Loves You, Porgy"). A hurricane approaches.

Scene 4 – With disparate prayers ("Oh, Doctor Jesus"),

Awaiting the hurricane (original production) |

![]()

Scene I – The next night, the chorus tenderly comforts the newly-widowed Clara ("Clara, Clara, Don't You Be Downhearted"). Sportin' Life mocks their solemnity. Crown sneaks into Catfish Row and is stabbed and strangled by Porgy, who triumphantly boasts that Bess now has a real man.

Scene 2 – The next afternoon, a detective and a coroner require Porgy to identify Crown's corpse; superstitious, he refuses and is arrested for contempt. Sportin' Life plies Bess with "happy dust" and tempts her to leave with him to live a high life together ("There's a Boat Dat's Leavin' Soon for New York").

Scene 3 – One week later, as Catfish Row stirs to life ("Good Mornin', Sistuh") Porgy returns in high spirits but is devastated to learn that Bess is gone ("Oh, Bess, Oh Where's My Bess").

![]() The endings of the three versions underline the essential differences among their genres.

The endings of the three versions underline the essential differences among their genres.

In the novel, Bess has gone to Savannah with a half-dozen stevedores. The book concludes:

Porgy was an old man. The early tension that had characterized him, the mellow mood that he had known for one eventful summer, both had gone; and in their place [Maria] saw a face that sagged wearily, and the eyes of age lit only by a faint reminiscent flow from suns and moons that had looked into them, and had already dropped down the west. She looked until she could bear the sight no longer; then she stumbled into her shop and closed the door, leaving Porgy and the goat alone in an irony of morning sunlight.The elegiac narrative hangs suspended in time and space, leaving readers' imaginations to ponder personal thoughts in solitude for as long as we wish – an ideal thoughtful ending for a book, and especially one aspiring to transcend its immediate story and setting with themes of timeless and universal significance.

In the play Bess, drunk and addicted, has run off with Sportin' Life to New York. Porgy keeps asking directions – "Which way dat?" – and is told "Up Nort' – past de Custom House." Blinded by love, ignoring the women's pleas, he turns his goat and drives out of Catfish Row as church bells chime the hour and the gate clangs shut behind him. Although more definite than the novel, the ending of the play focuses on the desperation of Porgy's quest while leaving open the chance that he might come to his senses and return to the community he needs, inspiring audiences to leave with a collective tangible image of the novel's open ending.

The opera follows the play but with musical enrichment that vastly enhances its impact. In a forceful trio, Porgy asks about Bess while Maria and Serena balance his pleas by urging him to forget her ("She was no good," "She worse than dead").

On his way– final scene (original production) |

Oh Lawd, I'm on my way.Even though one of the most alluring tunes in the entire opera, we hear it for barely a minute so that it resonates long past a succinct instrumental postlude, thus brilliantly using the power of music to underscore the thematic core of invoking ongoing faith to conquer futility as Porgy, and symbolically his entire people, set out against crushing odds on a bold and daunting journey toward an uncertain destiny in a far-off promised land.

I'm on my way to a Heav'nly Lan' –

Oh Lawd, it's a long, long way,

but You'll be there to take my han'.

No opera has a more genuinely moving ending.

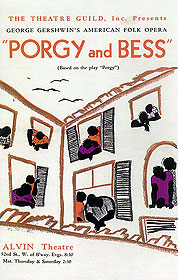

![]() Gershwin had been offered a $5,000 bonus by the Metropolitan Opera to produce the premiere of the opera but he turned it down in favor of the Theatre Guild, which had mounted the play – a wise move as the Met only would have programmed it twice and Gershwin wanted to reach a wider audience rather than just the cultured elite. Moreover, the creators insisted upon an all-black cast, which for the Met at the time would have been unthinkable.

Gershwin had been offered a $5,000 bonus by the Metropolitan Opera to produce the premiere of the opera but he turned it down in favor of the Theatre Guild, which had mounted the play – a wise move as the Met only would have programmed it twice and Gershwin wanted to reach a wider audience rather than just the cultured elite. Moreover, the creators insisted upon an all-black cast, which for the Met at the time would have been unthinkable.  Despite the dearth of operatic opportunities available at the time to anyone of color, most of the cast was classically-educated, with the ironic result, as David Ewen put it, that they had purged "Negroid qualities" from their speech and singing, and had to be encouraged to re-learn and use colloquial inflection. Thus Todd Duncan, the conservatory-trained head of the music department of Howard University who was to play Porgy, was not fond of jazz, auditioned with a recital of lieder and classical arias, and went with Gershwin to Charleston to study the native dialect. Anne Brown (Bess) and Ruby Elzy (Serena) both were Juilliard graduates. Warren Coleman (Crown) hailed from the New England Conservatory of Music. Abbie Mitchell (Clara) studied in Paris and headed the vocal department of the Tuskegee Institute. The Eva Jessaye Choir and conductor Alexander Smallens came from the Four Saints in Three Acts operatic production. The only exception was John Bubbles, half of a dazzling song and tap-dance vaudeville act (his partner Ford Buck was cast in the minor role of Mingo), whose carefree personality and stylish exhuberance fairly burst from the screen in the 1943 Cabin in the Sky, and who was a brilliant fit for the character of Sportin' Life, but whose penchant for ad-libbing caused fits for the production – Duncan recalled that Bubbles "would hold a particular note two beats on Monday night but on Tuesday night he might sustain that same note for six beats" and thus "would reconceive Mr. Gershwin's score as often as he sang it." Oscar Levant recalled that Bubbles was nearly fired for his frequent absences from rehearsals, but that Gershwin revered him as "the black Toscanini" (whatever he meant by that!).

Despite the dearth of operatic opportunities available at the time to anyone of color, most of the cast was classically-educated, with the ironic result, as David Ewen put it, that they had purged "Negroid qualities" from their speech and singing, and had to be encouraged to re-learn and use colloquial inflection. Thus Todd Duncan, the conservatory-trained head of the music department of Howard University who was to play Porgy, was not fond of jazz, auditioned with a recital of lieder and classical arias, and went with Gershwin to Charleston to study the native dialect. Anne Brown (Bess) and Ruby Elzy (Serena) both were Juilliard graduates. Warren Coleman (Crown) hailed from the New England Conservatory of Music. Abbie Mitchell (Clara) studied in Paris and headed the vocal department of the Tuskegee Institute. The Eva Jessaye Choir and conductor Alexander Smallens came from the Four Saints in Three Acts operatic production. The only exception was John Bubbles, half of a dazzling song and tap-dance vaudeville act (his partner Ford Buck was cast in the minor role of Mingo), whose carefree personality and stylish exhuberance fairly burst from the screen in the 1943 Cabin in the Sky, and who was a brilliant fit for the character of Sportin' Life, but whose penchant for ad-libbing caused fits for the production – Duncan recalled that Bubbles "would hold a particular note two beats on Monday night but on Tuesday night he might sustain that same note for six beats" and thus "would reconceive Mr. Gershwin's score as often as he sang it." Oscar Levant recalled that Bubbles was nearly fired for his frequent absences from rehearsals, but that Gershwin revered him as "the black Toscanini" (whatever he meant by that!).

Gershwin was thrilled during rehearsals, stating, "I think the music is so marvelous I can't believe I wrote it!" (Jablonski, for one, considers this confidence rather than conceit – the same assurance that led Gershwin to send his publisher his score for the first two acts before writing the third.) Yet when first performed in a Boston tryout on September 30 Porgy and Bess ran over three hours plus two intermissions, and it was agreed that nearly a quarter had to be cut. Beyond extensive abridgements, including paring into a brief solo the stirring final trio in which two women try in vain to dissuade Porgy from leaving, entire numbers were deleted, including the Jasbo Brown opening, the innovative "Six Prayers" and Porgy's "Buzzard Song," one of Duncan's three arias in the same scene which he had to sing on his knees and that sorely tested his stamina.

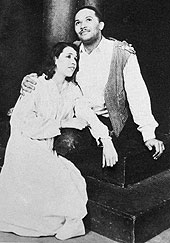

Todd Duncan and Anne Brown – the original Porgy and Bess |

![]() The Boston premiere spawned a 15-minute ovation, but critical reaction to the New York opening was decidedly mixed. Perhaps baffled by the novelty, several critics felt uncomfortable categorizing it based on their traditional perspective, disapproving the overall conception as an "indiscriminate, ill-fused mixture" (Frederick Jacobi) that lacked homogeneity (Samuel Chotzinoff) and even reproving the wonderful songs as intruding upon the integrity of the drama (Lawrence Gilman, who called the fervent "Bess, You Is My Woman Now" "sure-fire trash"). The most severe vituperation came from Virgil Thompson, who called it "crooked folklore and half-way opera, a strong but crippled work" with recitatives "as ineffective as anything I've heard," and slammed Gershwin's "fidgety accompaniments," "over-rich and vulgar scoring," "gefilte fish orchestration" and "lack of understanding of all the major problems of form, continuity and serious or direct musical expression."

The Boston premiere spawned a 15-minute ovation, but critical reaction to the New York opening was decidedly mixed. Perhaps baffled by the novelty, several critics felt uncomfortable categorizing it based on their traditional perspective, disapproving the overall conception as an "indiscriminate, ill-fused mixture" (Frederick Jacobi) that lacked homogeneity (Samuel Chotzinoff) and even reproving the wonderful songs as intruding upon the integrity of the drama (Lawrence Gilman, who called the fervent "Bess, You Is My Woman Now" "sure-fire trash"). The most severe vituperation came from Virgil Thompson, who called it "crooked folklore and half-way opera, a strong but crippled work" with recitatives "as ineffective as anything I've heard," and slammed Gershwin's "fidgety accompaniments," "over-rich and vulgar scoring," "gefilte fish orchestration" and "lack of understanding of all the major problems of form, continuity and serious or direct musical expression."

Rouben Mamoulian |

Others, though, were thrilled. Brooks Atkinson, the New York Times drama critic, wrote: "Mr. Gershwin has contributed something glorious to the spirit of the Heywards' community legend" by injecting personal feeling that had been inarticulate in the play. Olin Downes, the Times music critic, commended the animated acting, stating that if the Metropolitan Opera chorus could ever emulate the action of the Negro cast "it would be not merely refreshing but miraculous." A. Walter Kramer in Musical America cited "the score of amazing fluency." As with the play, Mamoulian's stage direction was lavishly praised: "filled with a visual music of its own which is unfailingly rhythmic, unforgettable in the ever-changing beauty of its groupings, extraordinary in its invention and amazing in the atmospheric details it employs" (John Mason Brown in the New York Post), "a symphony in stage movement with actors, actions and music synthesized as never before" (George Holland in the New York American) and "a riot of imagination and richness" (Marcia Davenport in Stage). Indeed Joseph Horowitz contends that Mamoulian's role in not only mounting but crafting the opera has been severely underrated. Hollis Alpert credits him with encouraging the cast to be spontaneous. Davenport sought to puncture critical concern over whether Porgy and Bess was a true opera by proposing a simple test: that it unfolds as much to the ear as to the eye and that it would not make the same impression without music.

![]() Especially scathing censure came from black artists at the time. Duke Ellington wrote that Gershwin had borrowed from everyone from Liszt to a kazoo band but had only produced "lampblack Negroisms" and declared: "No Negro could possibly be fooled by Porgy and Bess." Ralph Matthews similarly asserted that it had "a conservatory twang" and "none of the deep sonorous incantations so frequently identified with racial offerings." Hall Johnson credited the "natural racial qualities" of the cast as saving the opera from being "as stiff and artificial in performance as it is on paper" and investing the proceedings with a "convincing semblance of plausibility."

Especially scathing censure came from black artists at the time. Duke Ellington wrote that Gershwin had borrowed from everyone from Liszt to a kazoo band but had only produced "lampblack Negroisms" and declared: "No Negro could possibly be fooled by Porgy and Bess." Ralph Matthews similarly asserted that it had "a conservatory twang" and "none of the deep sonorous incantations so frequently identified with racial offerings." Hall Johnson credited the "natural racial qualities" of the cast as saving the opera from being "as stiff and artificial in performance as it is on paper" and investing the proceedings with a "convincing semblance of plausibility."

Al Hirschfeld caricature for a theatre program |

It only seems fair to note that the image of race relations depicted in the opera is hardly romanticized or even downplayed. Two white characters (a detective and a policeman) are intrusive and disruptive forces in the community, constantly intimidating the residents, treating them like infants and dragging them off to jail on flimsy pretexts (and barely offset by the only other white, the benevolent Mr. Archdale).

Respectability – a 1993 U.S. stamp! |

The problem was undoubtedly exacerbated by the n-word. Few writers mention it and none of the recordings, not even the roughly contemporaneous ones, contains it (presumably because it was not in any of the song lyrics, but only in the recitatives). Yet the n-word appears to have been routine and accepted in actual performances of the opera at least through the early 1940s, when a revival cast insisted upon removing it altogether. Goddard Lieberson's notes to the first nearly-complete recording in 1951 included a rather gingerly-phrased explanation that suggests prevalence up to that time: "Sometimes, happily, times change; and with the times ethical values. It seemed proper, when we turned to this production of Porgy and Bess, to eliminate certain words in the lyrics which, in racial terms, had proven offensive, and the first person to join enthusiastically in the making of these changes was Ira Gershwin himself, who has supplied new lyrics when they seemed desirable." Comparable lines of the opera and play suggest that several iterations were replaced with "dummy" and similarly milder generic insults.

Page 1 of the autograph score |

![]()

Perhaps fueling the critical confusion, Gershwin proclaimed Porgy and Bess to be a new genre – a "folk opera." He explained: "Because Porgy and Bess deals with Negro life in America it brings to the operatic form elements that have never before appeared in opera, and I have adopted every method to utilize the drama, the humor, the superstitions, the religious fervor, the dancing and the irrepressible high spirit of the race. If in doing this I have created a new form which combines opera and theater, then this new form has grown quite naturally out of the material." Writing in 1970, David Ewen echoed: "So completely did Gershwin assimilate and absorb the elements of Negro song and dance into his own writing" that he was "able to produce a musical art basically Negro in physiognomy and spirit, expressive of the heart and soul of an entire race." Such claims may seem painfully patronizing nowadays, and perhaps time has helped to place Porgy and Bess in an historical perspective so far removed from modern understanding of African-American culture, society and achievement that it can be regarded as artistic license applied to a bygone fiction. In that light, Mellers credits it as part of a continuum, extending the central quality of Mozart and Verdi operas – at once a social art, an entertainment and a human experience with unexpectedly disturbing implications, to which we might add that for great art the relevance, meaning and potency of those implications often evolve over time in ways that the creators may never have envisioned.

Gershwin was proud that, although intended to emulate genuine black folk music, all the tunes were original, excepting only the vendors' genuine street cries. He defended criticism that Porgy and Bess was less a serious opera than an excuse to string together a set of songs: "Songs are entirely in the operatic tradition. Many of the most successful operas of the past have had great songs. … Carmen is almost a collection of song hits." Even so, as if to unwittingly validate the criticism, few commentators have addressed the musical structure of Porgy and Bess aside from the celebrated set pieces.

![]()

By Broadway standards, the initial run of 124 performances fell short of success, although it far exceeded the mere handful of renditions that any new opera could reasonably expect in its inaugural season. Attendance was bolstered neither by lowering the ticket prices by 25%, nor by a five-city tour (which bore the distinction of integrating the audience for the first time at the National Theatre in Washington, DC after the cast otherwise refused to perform there and Duncan rejected compromises of allowing blacks to attend only matinees or sit only in the balcony).  A 1938 West Coast revival featured all the original leads except Bubbles, but his replacement, Avon Long, soon made the role of Sportin' Life his own. Critics were mostly won over by a 1941 production that eclipsed the popularity of the original, running for a year on Broadway and then an 18-month tour, although it made further cuts, trimmed the orchestration and relied heavily on spoken dialog in lieu of Gershwin's extensive recitatives. The 1943 European premiere in Copenhagen was withdrawn after the Nazis threatened to bomb the theatre. In 1952 the State Department subsidized a four-year touring company (which launched the career of Leontyne Price), but although intended as Cold War propaganda to acknowledge past oppression, tout modern progress and display equal rights for black artists (until then European productions had still used blackface), without proper historical perspective it partially backfired by reinforcing foreign racist stereotypes. The cast, though, served as good-will ambassadors in their public contacts and promotional appearances. In 1955 the production became the first American opera ever to be performed at La Scala.

A 1938 West Coast revival featured all the original leads except Bubbles, but his replacement, Avon Long, soon made the role of Sportin' Life his own. Critics were mostly won over by a 1941 production that eclipsed the popularity of the original, running for a year on Broadway and then an 18-month tour, although it made further cuts, trimmed the orchestration and relied heavily on spoken dialog in lieu of Gershwin's extensive recitatives. The 1943 European premiere in Copenhagen was withdrawn after the Nazis threatened to bomb the theatre. In 1952 the State Department subsidized a four-year touring company (which launched the career of Leontyne Price), but although intended as Cold War propaganda to acknowledge past oppression, tout modern progress and display equal rights for black artists (until then European productions had still used blackface), without proper historical perspective it partially backfired by reinforcing foreign racist stereotypes. The cast, though, served as good-will ambassadors in their public contacts and promotional appearances. In 1955 the production became the first American opera ever to be performed at La Scala.

A lavish 1959 movie adaptation reverted to a standard Hollywood musical dialog-and-song structure and not only rekindled the debate over distorting racial history but added a new critical wrinkle – that massive changes made in the name of dignity, sensitivity and taste to reduce stereotypes (including purging much of the dialect) served to neuter the original in favor of "picturesque poverty." While the black press was generally supportive, many progressives rued the continued absence of cinematic roles in which black actors could take genuine pride. (Harry Belafonte refused the lead role in the movie, acknowledging that the music was great but that "all that crapshooting and razors and lusts and cocaine is the old conception of the Negro.") After 15 years rights to the movie reverted to the Gershwin estate, which has barred its public distribution ever since. (Due to essentially perpetual American copyrights, the Gershwin estate continues to tightly control the licensing of Porgy and Bess as well as all his other works. So far, consistent with the creators' wishes, it has only allowed productions of the opera with black performers.)

Alpert notes that by the 1970s the social controversy had largely subsided so the work could be respected as a period piece. Indeed, the modern era began in 1975 with a Cleveland concert performance followed by a 1976 bicentennial production by the Houston Opera that for the first time restored the entire original three-hour score, to nearly unanimous acceptance and critical acclaim, in which form it generally has been given ever since.  Even so, a 2006 Nashville production reverted to the cuts from the New York opening in the belief that the full version had been merely a rough draft that failed to represent Gershwin's refinements and final thoughts. The ultimate badge of acceptance by the cultural elite arrived in 1985, when, after a half-century of being snubbed by the Metropolitan Opera, Porgy and Bess was added to its repertory.

Even so, a 2006 Nashville production reverted to the cuts from the New York opening in the belief that the full version had been merely a rough draft that failed to represent Gershwin's refinements and final thoughts. The ultimate badge of acceptance by the cultural elite arrived in 1985, when, after a half-century of being snubbed by the Metropolitan Opera, Porgy and Bess was added to its repertory.

![]() Evans hails Porgy and Bess as a meeting point for the two divergent paths of serious and popular music in Gershwin's career (and, we might add, of all music of the past century). Indeed, Gershwin shines both in the atmospheric instrumental sections (the hurricane, Catfish Row coming to life, the Crown-Robbins and Crown-Porgy fights – the former a genuine fugue!) and even more memorably in the variety and magnificence of the songs – the ravishing lullaby "Summertime" (which Gershwin surely knew would be a smash hit, reprising it three times), the jaunty (if sexist) "A Woman is a Sometime Thing," the profoundly mournful "Gone, Gone, Gone," the heartrending "My Man's Gone Now," the energized "Oh the Train is at the Station," the carefree "I Got Plenty o' Nuttin'," the classically-structured "Buzzard Song" dramatic aria, the lushly romantic "Bess, You is My Woman Now," the iconoclastic "It Ain't Necessarily So," the work-song "It Takes a Long Pull to Get There," the prayerful "De Lawd Shake de Heavens," the arrogantly macho "A Red-Headed Woman," the wily "There's a Boat Dat's Leavin' Soon for New York," the potent lament "Bess, Oh Where's My Bess," and the closing "Oh Lawd, I'm on My Way" that defies any simplistic description or emotion.

Evans hails Porgy and Bess as a meeting point for the two divergent paths of serious and popular music in Gershwin's career (and, we might add, of all music of the past century). Indeed, Gershwin shines both in the atmospheric instrumental sections (the hurricane, Catfish Row coming to life, the Crown-Robbins and Crown-Porgy fights – the former a genuine fugue!) and even more memorably in the variety and magnificence of the songs – the ravishing lullaby "Summertime" (which Gershwin surely knew would be a smash hit, reprising it three times), the jaunty (if sexist) "A Woman is a Sometime Thing," the profoundly mournful "Gone, Gone, Gone," the heartrending "My Man's Gone Now," the energized "Oh the Train is at the Station," the carefree "I Got Plenty o' Nuttin'," the classically-structured "Buzzard Song" dramatic aria, the lushly romantic "Bess, You is My Woman Now," the iconoclastic "It Ain't Necessarily So," the work-song "It Takes a Long Pull to Get There," the prayerful "De Lawd Shake de Heavens," the arrogantly macho "A Red-Headed Woman," the wily "There's a Boat Dat's Leavin' Soon for New York," the potent lament "Bess, Oh Where's My Bess," and the closing "Oh Lawd, I'm on My Way" that defies any simplistic description or emotion.

Two numbers especially seem remarkably innovative in light of subsequent musical history. In Act II, Maria castigates Sportin' Life in a forerunner of rap – even apart from the biting lyrics, she delivers her jabs in partly-spoken rhythmic and pitched declamation:

I hates yo' struttin' style,Although it didn't survive the early cuts, the hurricane scene began with the exceptional "Six Prayers" in which two sopranos, an alto, a tenor and two basses all sing separate texts simultaneously that are barely intelligible and never make any pretense of meshing yet somehow unite in their individualistic fervor – an instance of aleatory music two decades before avant-garde composers relished such effects! Heyward recalled its inspiration – that during their stay on Folly Island Gershwin had been inspired by sound that transfixed him outside a Gullah prayer meeting that "consisted of perhaps a dozen voices raised in loud rhythmic prayer … while each had started at a different time, upon a different theme" and that "with the actual words lost, and the inevitable pounding of the rhythm, produced an effect almost terrifying in its primitive intensity."

Yes, sir, and yo' god damn silly smile

an' yo' ten cent di'mons an' yo' fi'cent butts,

Oh, I hates yo' guts.

Some night when you is full of gin an' don't know I's about,

I'm goin' to take you by de tail an' turn you inside out.

I's figgerin' to break yo' bones, yes sir, one by one.

An' then I's goin' to carve you up an' hang you in de sun.

From the very outset the songs took on lives of their own.  "Summertime" in particular is one of the most popular songs ever written and has had literally thousands of recordings, ranging through such disparate versions as Billie Holliday's 1936 mellow swing, the Marcels' 1961 doo-wop, Billy Stewart's 1966 vocal acrobatics and Janis Joplin/Big Brother's deeply personal 1968 blues improvisation.

"Summertime" in particular is one of the most popular songs ever written and has had literally thousands of recordings, ranging through such disparate versions as Billie Holliday's 1936 mellow swing, the Marcels' 1961 doo-wop, Billy Stewart's 1966 vocal acrobatics and Janis Joplin/Big Brother's deeply personal 1968 blues improvisation.

A trio of extensive jazz interpretations of the score anticipated release of the movie. In a lushly orchestrated big-band 1957 double Verve album (complete with an 11-minute overture by Russell Garcia), Ella Fitzgerald and Louis Armstrong lend their distinctive voices and styles (and Armstrong's trumpet) to all the roles and treat the songs as worthy abstract thematic material with little connection to the original context or the underlying meaning of the lyrics. More traditional but with extended resourceful digressions is a 1959 Verve album by pianist Oscar Peterson's trio (with Ray Brown, bass and Ed Thigpen, drums). Perhaps the most extraordinary is a highly-acclaimed 1958 Miles Davis Columbia album featuring inventive arrangements and orchestrations by Gil Evans that approaches the opera as a series of brilliant and far-reaching meditations and fantasies, taking far more interpretive liberties than most artists would dare.

Other sets include those by Sammy Davis, Jr. and Carmen McRae (Decca, 1959), Harry Belafonte and Lena Horne (RCA, 1959), Ray Charles and Cleo Laine (RCA, 1976) and the Modern Jazz Quartet (Atlantic, 1966).

Other sets include those by Sammy Davis, Jr. and Carmen McRae (Decca, 1959), Harry Belafonte and Lena Horne (RCA, 1959), Ray Charles and Cleo Laine (RCA, 1976) and the Modern Jazz Quartet (Atlantic, 1966).

More traditional instrumental reductions began with a 25-minute suite created and conducted by Gershwin himself to create "buzz" for the roadshow tour following the initial Broadway run. Rather remarkably, its five sections bypass most of the obvious hit tunes (just "Summertime" (of course), "I Got Plenty of Nuttin'," "Bess, You Is My Woman Now" and the finale) in favor of the fight fugue, hurricane and awakening, and even restores the Jasbo Brown blues music that opera audiences wouldn't get to hear, all of which Gershwin clearly cherished. Subsequently forgotten, it was rediscovered in 1958 and titled Catfish Row to distinguish it from a 1942 abridgement of similar length, Porgy and Bess – A Symphonic Picture, by Robert Russell Bennett, that adds "There's a Boat That's Leavin' for New York" and "It Ain't Necessarily So" as well as the more obscure vendors' calls, requiem and picnic music.  Commissioned and introduced by Fritz Reiner (who was hardly known as a pop culture enthusiast), his 1945 Columbia recording with his Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra displays far more spirit than the rigorous precision for which he is famed. Yet its first recording, albeit shortened by omitting the first third so as to fit on four 12" sides, was by Alfred Wallenstein and the Los Angeles Philharmonic for Decca in August 1944, while Reiner's label was subject to a musician's strike and recording ban. 1945 also saw a remarkably idiomatic set of six songs arranged for violin and piano by Gershwin's Hollywood friend, Jascha Heifetz, who applies his phenomenal technique to a winning combination of blues and virtuosity.

Commissioned and introduced by Fritz Reiner (who was hardly known as a pop culture enthusiast), his 1945 Columbia recording with his Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra displays far more spirit than the rigorous precision for which he is famed. Yet its first recording, albeit shortened by omitting the first third so as to fit on four 12" sides, was by Alfred Wallenstein and the Los Angeles Philharmonic for Decca in August 1944, while Reiner's label was subject to a musician's strike and recording ban. 1945 also saw a remarkably idiomatic set of six songs arranged for violin and piano by Gershwin's Hollywood friend, Jascha Heifetz, who applies his phenomenal technique to a winning combination of blues and virtuosity.

![]() Given the passage of time, the evolution of style and the revisions to the score, it is both fascinating and significant to consider how Porgy and Bess was first performed as a basis for subsequent interpretation and an essential key (and possibly a corrective) for all who claim authenticity.

Given the passage of time, the evolution of style and the revisions to the score, it is both fascinating and significant to consider how Porgy and Bess was first performed as a basis for subsequent interpretation and an essential key (and possibly a corrective) for all who claim authenticity.

Our most remarkable and instructive document arose on July 19, 1935, six weeks before Gershwin dated his finished score, when he assembled his cast and a 43-piece orchestra in a CBS studio to test portions of his draft.  Five acetates were recorded. All are prefaced with Gershwin's spoken introduction and are of unique importance, presenting the singers for whom he drafted his music, fresh in the process of creating their roles under his personal guidance. All display a style far closer to grand opera than to Broadway. The first disc begins with Gershwin at the keyboard playing the (soon to be cut) Jasbo Brown blues with the same élan heard in his other solo recordings, while verbalising the dancers' choral chants, all at a rapid tempo suggesting eager anticipation and activity, followed by Abbie Mitchell (as Clara) singing "Summertime" in a rich, chesty voice enlivened with rhythmic elasticity and deeply-felt expressivity, capped by a long-lingering final note. Edward Matthews (Jake) then sings "A Woman is a Sometime Thing" with particular emphases, Gershwin conducts the impassioned orchestral Act I finale with special attention to textures, Ruby Elzy (Serena) sings the intensely moving "My Man's Gone Now" as a high soprano with exquisitely smooth melismas at the end of each verse, and Todd Duncan (Porgy) and Anne Brown (Bess) end with a deeply heartfelt "Bess, You Is My Woman Now" duet.

Five acetates were recorded. All are prefaced with Gershwin's spoken introduction and are of unique importance, presenting the singers for whom he drafted his music, fresh in the process of creating their roles under his personal guidance. All display a style far closer to grand opera than to Broadway. The first disc begins with Gershwin at the keyboard playing the (soon to be cut) Jasbo Brown blues with the same élan heard in his other solo recordings, while verbalising the dancers' choral chants, all at a rapid tempo suggesting eager anticipation and activity, followed by Abbie Mitchell (as Clara) singing "Summertime" in a rich, chesty voice enlivened with rhythmic elasticity and deeply-felt expressivity, capped by a long-lingering final note. Edward Matthews (Jake) then sings "A Woman is a Sometime Thing" with particular emphases, Gershwin conducts the impassioned orchestral Act I finale with special attention to textures, Ruby Elzy (Serena) sings the intensely moving "My Man's Gone Now" as a high soprano with exquisitely smooth melismas at the end of each verse, and Todd Duncan (Porgy) and Anne Brown (Bess) end with a deeply heartfelt "Bess, You Is My Woman Now" duet.  Neither Mitchell nor Elzy would formally record their roles, so this is a unique chance to hear them. Nor would Gershwin ever conduct any part of his opera again on record (and indeed we have only one other recording of him as a conductor – in a 1931 NBC broadcast of his Second Rhapsody).

Neither Mitchell nor Elzy would formally record their roles, so this is a unique chance to hear them. Nor would Gershwin ever conduct any part of his opera again on record (and indeed we have only one other recording of him as a conductor – in a 1931 NBC broadcast of his Second Rhapsody).

A fascinating appendage comes from a September 8, 1937 Gershwin Memorial Concert broadcast by CBS from the Hollywood Bowl, in which Duncan, Brown and Elzy reprised their roles, together with the Hall Johnson Choir and the Los Angeles Philharmonic led by Alexander Steinert, the musical coach of the first run. Spurred by the occasion, all 21 minutes of the excerpts are charged with a flood of vitality that brilliantly melds the technique of cultured operatic singing with the sheer emotion of unrestrained spirituals, and serves as a further document of the creators' original approach. Among the excerpts are the glorious choral Act I finale ("The Train is at the Station"), an ecstatic "Oh Lawd, I'm on My Way" abetted by bold stirring tempos, and Duncan's formidably impassioned "Buzzard Song" that, although cut from the show, remained a favorite of the composer. (An inadvertent contrast is provided by Lily Pons, a leading Met soprano whom Gershwin admired, who launches the selections by trilling "Summertime" with abundant beauty but scant feeling.  Although the concert begins with a depressingly ponderous orchestration of one of Gershwin's lithe piano preludes, its splendors include a delightfully raucous American in Paris led by Nathaniel Shilkret and coruscating accounts of the Rhapsody in Blue and Concerto in F played by Jose Iturbi and Oscar Levant.)

Although the concert begins with a depressingly ponderous orchestration of one of Gershwin's lithe piano preludes, its splendors include a delightfully raucous American in Paris led by Nathaniel Shilkret and coruscating accounts of the Rhapsody in Blue and Concerto in F played by Jose Iturbi and Oscar Levant.)

In the weeks following the premiere, Victor cut eight sides of the principal songs, supervised by the composer and directed by Alexander Smallens, whom Gershwin had hand-picked to conduct the Broadway run. Presumably to ensure upscale appeal at the cost of authenticity, two white (of course) Metropolitan Opera stars, Lawrence Tibbett and Helen Jepson, not only were cast as the title leads but also sang all the other highlights as well (Clara's "Summertime," Serena's "My Man's Gone Now" and Sportin' Life's "It Ain't Necessarily So" – Tibbett even voices all the crap-shooters' interjections during the first "Summertime" reprise). While the sheer vocal quality is undeniably lovely, Jepson's pronunciation is conspicuously European with rolled "r"s (rather ironic, as they both were born and bred in America) and most of the characterizations are blandly consistent (although Tibbett emulates the apposite accents in his "It Ain't Necessarily So").

Another hybrid came in November,

when Brunswick cut a single 78 of "Song Hits from Porgy and Bess for Dancing" featuring Edward Matthews singing "I Got Plenty o' Nuttin'" and "It Ain't Necessarily So." Yet, while Matthews was an original cast member (Jake), neither of the songs belonged to his character, but rather to Porgy and Sportin' Life, respectively. His singing is nicely colorful but, presumably to boost popular appeal, was accompanied by the white dance band of Leo Reisman, which tempered self-consciously "jazzy" arrangements with fox-trot back-beats. In 1942 Decca recorded six more big-band dance arrangements with the Reisman outfit, this time featuring Avon Long (singing not only his Sportin' Life songs with a fine touch of mischief but Jake's "A Woman Is a Sometime Thing" and Porgy's "I Got Plenty o'Nuttin'") and Helen Dowdy, promoted from her brief and highly stylized role of the Strawberry Woman street vendor in the original cast to Clara (an upbeat "Summertime") and Bess ("Bess You Is My Woman Now"). While characterization cedes to maintaining the uniform beat, in retrospect the mere willingness to disregard the authentic settings can be seen as the first essential step toward paving the way towards the inventive freedom of jazz improvisations of the opera's songs that still lay a decade into the future.

when Brunswick cut a single 78 of "Song Hits from Porgy and Bess for Dancing" featuring Edward Matthews singing "I Got Plenty o' Nuttin'" and "It Ain't Necessarily So." Yet, while Matthews was an original cast member (Jake), neither of the songs belonged to his character, but rather to Porgy and Sportin' Life, respectively. His singing is nicely colorful but, presumably to boost popular appeal, was accompanied by the white dance band of Leo Reisman, which tempered self-consciously "jazzy" arrangements with fox-trot back-beats. In 1942 Decca recorded six more big-band dance arrangements with the Reisman outfit, this time featuring Avon Long (singing not only his Sportin' Life songs with a fine touch of mischief but Jake's "A Woman Is a Sometime Thing" and Porgy's "I Got Plenty o'Nuttin'") and Helen Dowdy, promoted from her brief and highly stylized role of the Strawberry Woman street vendor in the original cast to Clara (an upbeat "Summertime") and Bess ("Bess You Is My Woman Now"). While characterization cedes to maintaining the uniform beat, in retrospect the mere willingness to disregard the authentic settings can be seen as the first essential step toward paving the way towards the inventive freedom of jazz improvisations of the opera's songs that still lay a decade into the future.

January 1938 brought a further curiosity when Paul Robeson, originally considered for the cast but unavailable at the time, cut four songs for HMV in London. In addition to three men's songs (Porgy's "A Woman Is a Sometime Thing," Jake's "It Takes a Long Pull to Get There" and Sportin' Life's "It Ain't Necessarily So"), he sings Clara's "Summertime," far removed from its original function of a mother's wistful, atmospheric lullaby.  All bear his trademark marvelously rich patina, but (much like Tibbett/Jepson) sacrifice expressivity for pure abstract musical quality, a feeling abetted by generic orchestrations. It seems significant that Robeson, one of the most outspoken members of his generation, apparently had no qualms over music that others shunned as condescending.

All bear his trademark marvelously rich patina, but (much like Tibbett/Jepson) sacrifice expressivity for pure abstract musical quality, a feeling abetted by generic orchestrations. It seems significant that Robeson, one of the most outspoken members of his generation, apparently had no qualms over music that others shunned as condescending.

The most comprehensive attempt at an "original cast" recording only came in May 1940 when Decca assembled the original choir, conductor, Duncan and Brown for a set of four 12" discs, followed two years later with a second volume of three 10" discs adding Matthews as Jake and Long as Sportin' Life. Greg Gormick notes that this preceded the 1943 Oklahoma album that often is cited as the first original cast recording. Yet it's a matter of degree – the Oklahoma set featured all the original cast in their actual roles, whereas here, as in the earlier selections, several songs originally sung by others were re-assigned to Duncan and Brown, the only two soloists in the first set. (To be fair, though, neither album truly qualified as the very first original cast recording; that honor went all the way back to Florodora – in 1900!) To their credit, the Decca sets include Porgy's dramatic "Buzzard Song," the Street Cries, the choral Requiem and even some recitative, all of which go well beyond the standard "greatest hits" to provide a fuller view of the scope of the work. Accompaniments are brisk and even impulsive yet pliant, documenting the emphases and tempos Gershwin instilled into Smallens.

Two later notable cast recordings of musical highlights deserve mention.

Although the 1959 Goldwyn movie was hardly an authentic presentation of the opera, in the absence of the movie itself the 52-minute soundtrack album (Columbia, 1959) remains our primary souvenir with which to judge the version through which much of the world came to know Porgy and Bess. Although not credited at the time, the lead actors' voices were dubbed by Robert McFerrin (for Sidney Poitier as Porgy) and Adele Addison (for Dorothy Dandridge as Bess). The only substitution acknowledged in the liner notes was Cab Calloway (as Sportin' Life) for Sammy Davis, Jr. who sang in the movie but was barred by contract from the Columbia album. The soundtrack music is blandly paced and too sweetly rearranged and re-orchestrated (by André Previn) yet credibly voiced, although with barely a suggestion of ethnicity. Beyond the standard pieces, it includes the choral "I Can't Sit Down" and "Oh, I Ain't Got No Shame," Crown's lusty "Red-Headed Woman" and a sliver of the percussion Occupational Humoresque. The songs on each LP side ran together without pause (and only the second had visible separations), resulting in abrupt transitions having little musical or dramatic sense (and creating unintentional irony jumping from "My Man's Gone Now" to "I Got Plenty o' Nuttin'" to "Bess You is My Woman Now").

Although the 1959 Goldwyn movie was hardly an authentic presentation of the opera, in the absence of the movie itself the 52-minute soundtrack album (Columbia, 1959) remains our primary souvenir with which to judge the version through which much of the world came to know Porgy and Bess. Although not credited at the time, the lead actors' voices were dubbed by Robert McFerrin (for Sidney Poitier as Porgy) and Adele Addison (for Dorothy Dandridge as Bess). The only substitution acknowledged in the liner notes was Cab Calloway (as Sportin' Life) for Sammy Davis, Jr. who sang in the movie but was barred by contract from the Columbia album. The soundtrack music is blandly paced and too sweetly rearranged and re-orchestrated (by André Previn) yet credibly voiced, although with barely a suggestion of ethnicity. Beyond the standard pieces, it includes the choral "I Can't Sit Down" and "Oh, I Ain't Got No Shame," Crown's lusty "Red-Headed Woman" and a sliver of the percussion Occupational Humoresque. The songs on each LP side ran together without pause (and only the second had visible separations), resulting in abrupt transitions having little musical or dramatic sense (and creating unintentional irony jumping from "My Man's Gone Now" to "I Got Plenty o' Nuttin'" to "Bess You is My Woman Now").

More important was Great Scenes From Porgy and Bess (RCA, 1963) which featured the stars of the 1952 touring production – an imposing Leontyne Price well-matched with William Warfield – and recruited John Bubbles from the original 1935 staging to reprise his creator's role of Sportin' Life (and thus preserving a belated and only opportunity to hear his colorful but fully musical presentation of that oily character). Both the finale and Bess's extended confrontation with Crown (sung by McHenry Boatwright) on Kittiwah Island are given nearly intact. Dynamically conducted by the versatile Skitch Henderson and vividly recorded in "Living Stereo," the singing is potent but well within both the letter and spirit of the opera and gives a fine impression of the energized mounting of the work to which so many audiences were exposed at the time.

![]() There seems to be no consensus as to an ideal recording of an ostensibly complete Porgy and Bess and, given the economic reality of the industry, may remain forever elusive. Perhaps that's a consequence of both the richness and problems of the score. Or perhaps it can serve as an appropriate symbol of Porgy's irrepressible quest for a distant and unattainable goal and, in turn, is a sobering reflection upon the human condition itself. In any event, there have only been eight studio recordings of the opera, and all bear at least some claim to historical and/or stylistic significance.

There seems to be no consensus as to an ideal recording of an ostensibly complete Porgy and Bess and, given the economic reality of the industry, may remain forever elusive. Perhaps that's a consequence of both the richness and problems of the score. Or perhaps it can serve as an appropriate symbol of Porgy's irrepressible quest for a distant and unattainable goal and, in turn, is a sobering reflection upon the human condition itself. In any event, there have only been eight studio recordings of the opera, and all bear at least some claim to historical and/or stylistic significance.

The following headnotes list the conductor; the singers of Porgy, Bess, Serena, Sportin' Life, Crown, Clara, Maria and Jake; the chorus; the orchestra (date, original label, timing in minutes). Note that the timings tend to be far more indicative of the amount of material included than pacing.

- Lehman Engel; Lawrence Winters, Camilla Williams, Inez Matthews, Avon Long, Warren Coleman, June McMechen, Helen Dowdy, Eddie Matthews; J. Rosamond Johnson Chorus; [unnamed] orchestra (1951, Columbia 3-LP set, 130')

Although advertised as complete ("every breathless moment of the opera recorded for your lasting pleasure"),

this pioneering venture reflects not only the then-standard cuts but some additional trimming as well (plus a few reinstatements, notably of Porgy's Act II "Buzzard Song"). The two leads were recruited from the New York City Center Opera but Coleman (as Crown), Dowdy (Maria) and Matthews (Jake) all harked back to the original 1935 cast, and Long (Sportin' Life) from the first revival, providing more than a touch of authenticity. All sing magnificently with a fine expressive blend of personalized character and stylized musicality. Subtlety abounds – Long provides an especially creepy villain, sweet and sly, and the white authorities are largely drained of malice. Led with sure theatrical instinct by Engel, already a Broadway veteran, the pacing is swift and the playing (by a New York pick-up group) crisp and lean. Conceived as a phonographic experience for home enjoyment, the enunciation is extremely clear and the fidelity excellent (albeit monaural). My only qualm lies in the raucous sound effects, which the producer intended "to substitute for those stage actions which, when seen in the theatre, add tension to the poignant story that unfolds before us." Thus we hear dice clanging, coins bombarding the collection plate, panicked shrieks as the hurricane hits, and wood cracking as Serena's door gives way to Crown, all hyper-realistic, highly amplified and far more prominent than in any theater, topped off throughout the two murders by fearsome grunts and blows worthy of a pro wrestling match. Intent aside, to me they sound ridiculous and detract from, rather than enhance, an otherwise superb presentation whose tangible enthusiasm is capped by Winters' seemingly spontaneous "Yes!" that punctuates his final line as he departs on his journey to an unknown realm.

this pioneering venture reflects not only the then-standard cuts but some additional trimming as well (plus a few reinstatements, notably of Porgy's Act II "Buzzard Song"). The two leads were recruited from the New York City Center Opera but Coleman (as Crown), Dowdy (Maria) and Matthews (Jake) all harked back to the original 1935 cast, and Long (Sportin' Life) from the first revival, providing more than a touch of authenticity. All sing magnificently with a fine expressive blend of personalized character and stylized musicality. Subtlety abounds – Long provides an especially creepy villain, sweet and sly, and the white authorities are largely drained of malice. Led with sure theatrical instinct by Engel, already a Broadway veteran, the pacing is swift and the playing (by a New York pick-up group) crisp and lean. Conceived as a phonographic experience for home enjoyment, the enunciation is extremely clear and the fidelity excellent (albeit monaural). My only qualm lies in the raucous sound effects, which the producer intended "to substitute for those stage actions which, when seen in the theatre, add tension to the poignant story that unfolds before us." Thus we hear dice clanging, coins bombarding the collection plate, panicked shrieks as the hurricane hits, and wood cracking as Serena's door gives way to Crown, all hyper-realistic, highly amplified and far more prominent than in any theater, topped off throughout the two murders by fearsome grunts and blows worthy of a pro wrestling match. Intent aside, to me they sound ridiculous and detract from, rather than enhance, an otherwise superb presentation whose tangible enthusiasm is capped by Winters' seemingly spontaneous "Yes!" that punctuates his final line as he departs on his journey to an unknown realm.

- Alexander Smallens; William Warfield, Leontyne Price, Helen Thigpen, Cab Calloway, John McCurry, Helen Colbert, Georgia Burke, Joseph James; [choir], RIAS-Unterhaltungsorchester Berlin (1952, Guild or Audite 2-CD set, 140')

This September 21, 1952 performance at the Titania-Palast in Berlin is an altogether remarkable souvenir of the U.S. State Department touring production produced by Robert Breen that introduced Porgy and Bess to so much of the world. A review in the Berliner Kurier summed it up well: "There is singing, shouting, crying, arguing, fighting, intermittent praying, dancing, howling, stamping … . Nobody seems to be acting but simply offering their unique temperament, vitality and sheer existence." Indeed, the infectious spontaneity and electrifying enthusiasm of the entire ensemble bursts out right after the orchestral opening when, in place of softly swaying couples, we hear a complex blend of stomping field chants hushed into respectful silence by the unassuming "Summertime" that, in turn, yields to a raucous crap game punctuated by the crowd's chatter and seemingly spontaneous verbal interjections that continue right through "A Woman Is a Sometime Thing" and most of the ensuing solo lines, some of which lend more to speech than song. Throughout there is an overall mix of superbly polished singing and thoroughly convincing characterization that achieves a seemingly impossible miracle of sounding both natural and operatic and that puts a fascinating spin on Gershwin's notion of a "folk opera." Smallens, who conducted the premiere Broadway engagement under Gershwin's direction, maintains an invigorating pace and wrests a fine accompaniment out of the local orchestra. Enunciation is clear, with even duets intelligible, although some of the dialect is standardized ("nuttin'" becomes "nothin'," "widder" becomes "widow"). The detective is especially harsh and even the residents respond to him in speech, reverting to song only after he leaves, thus augmenting the magnitude of their protective "curtain of silence." Several portions are restructured and become all the more effective dramatically. Thus Sportin' Life's sacrilegious "It Ain't Necessarily So" (with an added verse and Calloway's improvisational embellishments) no longer pops up out of nowhere during the picnic (which itself is enhanced with some frenetic drumming), but rather responds to Serena's condemnation of sinful behavior, "Good Mornin' Sistuh" is moved up to break the tension after Porgy kills Crown, and the "Buzzard Song" is moved to the final scene to darken the mood as Porgy is about to discover that Bess has run off. Among added features, two orchestral interludes serve to mark major passages of time between otherwise contiguous scenes (2 and 3 in both Acts II and III), several women individually comfort Clara as the choir opens Act III with a hymn, a dispute between the detective and the policeman underscores their mutual contempt for their charges, and an a capella trio of the three women gives their insistence upon an alibi a sly comic and even an empowering overtone. Although downstage voices occasionally are barely audible, the fidelity is fine. Overall, it's a wonderful, invigorating, thoroughly credible experience that glows with a unique spirit.

U.S. State Department touring production produced by Robert Breen that introduced Porgy and Bess to so much of the world. A review in the Berliner Kurier summed it up well: "There is singing, shouting, crying, arguing, fighting, intermittent praying, dancing, howling, stamping … . Nobody seems to be acting but simply offering their unique temperament, vitality and sheer existence." Indeed, the infectious spontaneity and electrifying enthusiasm of the entire ensemble bursts out right after the orchestral opening when, in place of softly swaying couples, we hear a complex blend of stomping field chants hushed into respectful silence by the unassuming "Summertime" that, in turn, yields to a raucous crap game punctuated by the crowd's chatter and seemingly spontaneous verbal interjections that continue right through "A Woman Is a Sometime Thing" and most of the ensuing solo lines, some of which lend more to speech than song. Throughout there is an overall mix of superbly polished singing and thoroughly convincing characterization that achieves a seemingly impossible miracle of sounding both natural and operatic and that puts a fascinating spin on Gershwin's notion of a "folk opera." Smallens, who conducted the premiere Broadway engagement under Gershwin's direction, maintains an invigorating pace and wrests a fine accompaniment out of the local orchestra. Enunciation is clear, with even duets intelligible, although some of the dialect is standardized ("nuttin'" becomes "nothin'," "widder" becomes "widow"). The detective is especially harsh and even the residents respond to him in speech, reverting to song only after he leaves, thus augmenting the magnitude of their protective "curtain of silence." Several portions are restructured and become all the more effective dramatically. Thus Sportin' Life's sacrilegious "It Ain't Necessarily So" (with an added verse and Calloway's improvisational embellishments) no longer pops up out of nowhere during the picnic (which itself is enhanced with some frenetic drumming), but rather responds to Serena's condemnation of sinful behavior, "Good Mornin' Sistuh" is moved up to break the tension after Porgy kills Crown, and the "Buzzard Song" is moved to the final scene to darken the mood as Porgy is about to discover that Bess has run off. Among added features, two orchestral interludes serve to mark major passages of time between otherwise contiguous scenes (2 and 3 in both Acts II and III), several women individually comfort Clara as the choir opens Act III with a hymn, a dispute between the detective and the policeman underscores their mutual contempt for their charges, and an a capella trio of the three women gives their insistence upon an alibi a sly comic and even an empowering overtone. Although downstage voices occasionally are barely audible, the fidelity is fine. Overall, it's a wonderful, invigorating, thoroughly credible experience that glows with a unique spirit.

- Russ Garcia; Mel Tormé, Frances Faye, Sallie Bahr, George Kirby, Johnny Hartman, Betty Roché, [no Maria], Frank Rosolino; Bethlehem Orchestra, Stan Levey Group (1956, Bethlehem 3-LP set, 108' [including narration])

Although billed as the second complete recording of Porgy and Bess (the Berlin performance would only surface on CD) this was nothing of the sort.

Variously called eclectic, inventive, a liberal reworking and "not so much a cohesive musical statement as a fascinating series of variations" (Howard Reich in the Chicago Tribune) the Bethlehem label's producers intended "a contemporary arrangement and improvisation … in which fresh ideas and innovations are fused into established vehicles for the purposes of artistic interpretations" to "bring Porgy and Bess up to date" and "bring the listener a delightfully different experience in recorded entertainment." (A mere glimpse at the original packaging – a bandana stuffed into a denim pocket – would have sufficed to dispel any thought of a serious operatic venture.) They further conceded an ulterior motive – to display the disparate artists their label had under contract. Although understandably given top billing, Duke Ellington and His Famous Orchestra is heard for a mere 48 seconds in an upbeat "Summertime" intro with a screaming trumpet (incongruously followed by Roché's sensitive, highly stylized vocal rendition). The accompaniments range from solo piano to jazz combo to full orchestra and support arrangements from straight-forward to be-bop, but despite the variety few seem to have much thematic significance to plot or lyrics and largely succeed in trivializing the inherent drama. Tormé, Bethlehem's only other star, known as "The Velvet Fog" for his smooth delivery, sounds very white but intensely musical. Faye, an openly bisexual nightclub singer known for her risqué material, nicely complements him with dusky worldliness. Other soloists have vague intonation that compromises the melodies.