|

As we sink ever deeper into the mire of Trump, it becomes increasingly hard to relegate the fears of past eras into a safe preserve of historical perspective or to seek solace in the ritual of religion and its promise of eventual release from worldly tension. Benjamin Britten (1913 – 1976) created his 1962 War Requiem at the height of the Cold War, a mere half-century after the "War to End All Wars" that inspired it was supposed to have chastened humanity into confronting the colossal cost of political aggression but instead had failed to usher in a promised era of peace and social progress. Today, yet another half-century later, the War Requiem cannot be consigned as a historical artifact but regains alarming relevance as the lessons of the past are semingly ignored.

The War Requiem is a remarkable confluence between England's greatest composer and one of its greatest poets, a bold venture in which Britten inserted the anti-war poetry of Wilfred Owen (1893 – 1918) into a modern setting of the traditional Roman Catholic Requiem Mass. As such, it gains added import when heard as the culmination of a long historical trend.

![]() Friction between sacred and secular music predates the War Requiem by at least 700 years. Polyphonic medieval motets juxtaposed Gregorian chant (in Latin) with up to four dances or songs (the latter in vernacular, and sometimes even different languages). While motets featured some correlation among the various texts and musical lines, they mostly were conceived horizontally with largely independent linear elements and little regard for their vertical alignment. Nowadays, the discrete texts and melodies (and resultant incidental dissonances) of motets tend to sound bizarre in comparison to their harmonious and carefully-constructed successors of later centuries.

Friction between sacred and secular music predates the War Requiem by at least 700 years. Polyphonic medieval motets juxtaposed Gregorian chant (in Latin) with up to four dances or songs (the latter in vernacular, and sometimes even different languages). While motets featured some correlation among the various texts and musical lines, they mostly were conceived horizontally with largely independent linear elements and little regard for their vertical alignment. Nowadays, the discrete texts and melodies (and resultant incidental dissonances) of motets tend to sound bizarre in comparison to their harmonious and carefully-constructed successors of later centuries.  And yet, as we become increasingly comfortable with the complexities of avant-garde and computer-generated music featuring layers of different keys and irregular rhythms, these ancient motets can seem surprisingly modern.

And yet, as we become increasingly comfortable with the complexities of avant-garde and computer-generated music featuring layers of different keys and irregular rhythms, these ancient motets can seem surprisingly modern.

The Renaissance brought a strict division between Church and popular music that largely persisted through the 19th century. Even so, secular elements occasionally intruded into musical settings of the full Mass.

Haydn's Missa in tempore belli (Mass in Time of War) was written in 1796 as Napoleon was advancing on Vienna, where it was to be performed. Although in the normally carefree key of C major and largely reflecting Haydn's irrepressible buoyancy, the opening and closing sections are spiked with uncharacteristic (and, at the time, possibly sacrilegious) militaristic trumpet fanfares and tympani rolls. (Haydn had added similar instrumentation to the second movement of his earlier Symphony # 100 in G – the so-called "Military Symphony" – but the effect there was purely for decorative color.) The drums and brass accents inject a palpable hint of anxiety and desperation into the Missa's traditional final soothing prayer for peace. One of the hallmarks of great music is its ability to speak to future generations, and Haydn's Missa did so with eloquence and cogency on January 19, 1973, when it highlighted a "Concert for Peace" led by Leonard Bernstein in Washington's National Cathedral as a protest to the Vietnam War and as a foil to the official concert celebrating Nixon's second inauguration being held that night at the nearby Kennedy Center.

Beethoven  seized upon a similar but more potent device for the devastatingly effective conclusion of his 1822 Missa Solemnis. In the final section of his score, which he inscribed as a "Prayer for inner and outer peace," a gently rolling 6/8 melody points the way to a satisfying end to the vast spiritual journey of the preceding hour, but then pounding drums and blaring fanfares intrude, as soloists and then the full chorus, in clipped, terrified tones, turn the prayer for peace into a desperate plea. Just as their fears subside and the flowing music appears headed once more for the expected comforting conclusion, the full orchestra interrupts with an angry fugue, capped by piercing brass and thunderous percussive chords. Calm returns, only to fall utterly silent twice again to disclose the tympani still rumbling menacingly in the distance. At last a final cadence follows, but it's brief and perfunctory, a deliberately unconvincing attempt to dispel the lingering qualms or to resolve such a massive and edgy structure. Beethoven crafted at best an unsettled expression of faith, a troubling question rather than a rousing affirmation or a soothing meditation. Thus he ended his most ambitious and arguably greatest work with a shrewd but unmistakable caution that a mind preoccupied with thoughts of war cannot truly be at ease.

seized upon a similar but more potent device for the devastatingly effective conclusion of his 1822 Missa Solemnis. In the final section of his score, which he inscribed as a "Prayer for inner and outer peace," a gently rolling 6/8 melody points the way to a satisfying end to the vast spiritual journey of the preceding hour, but then pounding drums and blaring fanfares intrude, as soloists and then the full chorus, in clipped, terrified tones, turn the prayer for peace into a desperate plea. Just as their fears subside and the flowing music appears headed once more for the expected comforting conclusion, the full orchestra interrupts with an angry fugue, capped by piercing brass and thunderous percussive chords. Calm returns, only to fall utterly silent twice again to disclose the tympani still rumbling menacingly in the distance. At last a final cadence follows, but it's brief and perfunctory, a deliberately unconvincing attempt to dispel the lingering qualms or to resolve such a massive and edgy structure. Beethoven crafted at best an unsettled expression of faith, a troubling question rather than a rousing affirmation or a soothing meditation. Thus he ended his most ambitious and arguably greatest work with a shrewd but unmistakable caution that a mind preoccupied with thoughts of war cannot truly be at ease.

The specialized Missa pro defunctus (Mass for the dead) was codified in 1570. Perhaps in deference to its especially respectful function, musical settings of the Requiem Mass tended to remain solemn and comforting and thus relatively immune from the incursion of disturbing popular influences. Yet, the sweeping emotions of Romanticism brought an infusion of secular features there, too.

Hector Berlioz designed his 1837 Grande Messe des Morts  for massive forces by supplementing his augmented orchestra and six-part chorus with 16 tympani, four gongs, ten cymbals and four brass bands arrayed in opposite corners. The sheer magnitude of the resulting sound eclipsed the text to convey a tangible depiction of the terror of the day of judgment. While using a more conventional complement of performers, Giuseppe Verdi's 1874 Missa da Requiem was overtly theatrical (and was hailed – indeed, disparaged – as his finest opera), with hyper-dramatic outbursts, ravishing arias and a chilling conclusion of haunting dread in which the soprano, as softly as possible (marked pppp) at the very bottom of her range (middle C) and utterly drained of feeling (the score specifies "morendo" – "dying"), barely manages to growl two final pleas of "libera me" as though, having tried all the standard approaches to prayer, she is left stripped of any armor religion might provide to confront the worst fear of all for a culture steeped in faith – that at the very end of life's struggle there will be no salvation at all but only eternal silence.

for massive forces by supplementing his augmented orchestra and six-part chorus with 16 tympani, four gongs, ten cymbals and four brass bands arrayed in opposite corners. The sheer magnitude of the resulting sound eclipsed the text to convey a tangible depiction of the terror of the day of judgment. While using a more conventional complement of performers, Giuseppe Verdi's 1874 Missa da Requiem was overtly theatrical (and was hailed – indeed, disparaged – as his finest opera), with hyper-dramatic outbursts, ravishing arias and a chilling conclusion of haunting dread in which the soprano, as softly as possible (marked pppp) at the very bottom of her range (middle C) and utterly drained of feeling (the score specifies "morendo" – "dying"), barely manages to growl two final pleas of "libera me" as though, having tried all the standard approaches to prayer, she is left stripped of any armor religion might provide to confront the worst fear of all for a culture steeped in faith – that at the very end of life's struggle there will be no salvation at all but only eternal silence.

In the meantime, the supremacy of Latin was being challenged. In his 1869 Deutches Requiem Johannes Brahms broke the language barrier – the lyrics were wholly in German and the prescribed text was derived from the Lutheran Bible. Leoš Janácek cast his 1926 Glagolitic Mass using the traditional text but in a more primal vernacular – Old Slavonic, which had been in liturgical use in Slavic regions for a millennium.

Due to their scope and the magnitude of their performing forces, none of the Romantic-era Requiems was suitable for performance as an integral part of a religious service but rather were clearly destined for the concert hall.  Even so, possibly in reaction to these works and the secularizing trend they threatened, in 1903 Pope Pius X sought to clamp down on the profanation of liturgical music by providing a code of instructions to restore as the supreme models for worship Gregorian chant and XVI Century polyphony sung by choirs of boys and devout men, with occasional organ accompaniment. Among other elements, he refused to have chant "preceded by long preludes or interrupt[ed] with intermezzo pieces," condemned solos, required that all text be in Latin, limited the use of wind instruments (and then only "provided the composition and accompaniment be written in grave and suitable style") and forbade pianos and "noisy or frivolous instruments such as drums, cymbals, bells and the like."

Even so, possibly in reaction to these works and the secularizing trend they threatened, in 1903 Pope Pius X sought to clamp down on the profanation of liturgical music by providing a code of instructions to restore as the supreme models for worship Gregorian chant and XVI Century polyphony sung by choirs of boys and devout men, with occasional organ accompaniment. Among other elements, he refused to have chant "preceded by long preludes or interrupt[ed] with intermezzo pieces," condemned solos, required that all text be in Latin, limited the use of wind instruments (and then only "provided the composition and accompaniment be written in grave and suitable style") and forbade pianos and "noisy or frivolous instruments such as drums, cymbals, bells and the like."

Pressure for progressive reform led Pope John XXIII to convene a Second Vatican Council that culminated in the Musicam Sacram, a 1967 instructional manual that gave due consideration to popular culture and traditions of various peoples and ethnicities, permitted vernacular translations of the traditional mass and, while maintaining pride of place to Gregorian chant, admitted the legitimacy of other musics "provided that they correspond to the spirit of the liturgical action and that they foster the participation of all the faithful." Yet despite the flexibility of that standard many limits remained: women were to be permitted in choirs but had to be placed outside the sanctuary; melodies for vernacular song were to be "approved by the competent territorial authority" based upon the extent to which they are inspired by "traditional melodies of the Latin liturgy;" and organs ceded their primacy to guitars and other instrumental accompaniment, but "those instruments which are, by common opinion and use, suitable for secular music only" were to be "altogether prohibited from every liturgical celebration and from popular devotions" – and were absolutely banned from masses for the dead.

While the War Requiem arose as these reforms were under way, and within the context of the Church of England, which deviates in several respects from papal Catholicism, it surely represented the boldest challenge yet to the established religious rituals of its time.

![]() Born into modest circumstances,

Born into modest circumstances,

Wilfred Owen |

William Plomer notes that Owen came to reject the conventional patriotic sentiments embodied in the poetry of Rupert Brooke, an idealized image of radiant British youth nobly sacrificing itself for glory and country. William Mann notes that the 20th century wrought a shift of attitudes from "the priests of Christianity whose founder expressly forbade the taking of human life" blessing weapons before battle and offering thanks for the heroism of the glorious dead, to "a new spirit of doubt whether any country had the moral right to demand that its sons become murderers and the victims of murder, and a conviction that the glorious dead must be respected, not as an example, but as a warning." Christopher Palmer posits that Owen extended the path blazed by Sassoon by writing "not about what soldiers gloriously did but what they had unforgivably been made to do to others and to suffer themselves." Palmer adds that while Owen entered the War as one of defense and liberation, he became disillusioned that it evolved into aggression, conquest and senselessly prolonged carnage, and that Owen further resented suppression by officialdom of truthful reporting of the fighting experience and its depiction of the enemy as a faceless monster rather than individual soldiers whom fate had placed in harm's way.

Siegfried Sassoon |

After his recovery Owen was assigned light administrative training duties but then re-embarked for the French front. One week before the Armistice he was killed in action. (It is said that his parents received the news of his death just as victory bells began to toll.)

As traced in Gertrude White's biography, at the time of Owen's death only four of his poems had been published. Barely known, he remained out of favor and became recognized as the greatest poet of the War only once painful memories began to fade. Although he identified with the late English Romantic poets' sense of fantasy generated from concrete imagery and symbolism, and his structures tended toward conventional forms (including many sonnets), he became recognized posthumously as an innovator of half-rhymes, in which vowel and consonant sounds (ours/powers, cattle/rattle) are bypassed in favor of consonance alone (as in: feet/fought, laughed/left, world/walled, killed/cold). White further notes Owen's favoring of alliteration (beginning nearby words with the same sound) and assonance (repeating a vowel sound throughout a phrase). All these stylistic techniques would seem to invite musical settings.

At one point Owen had been prepared to enter the service of the Church as a curate but became upset at his perception that established religion had diverged from the teachings of Jesus, whom he viewed as a conscientious objector: "One of Christ's essential commands was: Passivity at any price! Suffer dishonor and disgrace but never resort to arms. Be bullied, be outraged, be killed, but do not kill. … I think pulpit professionals are ignoring it very skillfully." Yet although he viewed war as a perversion of Christian values, he saw enlistment as necessary to validate his pacifist sentiments as beyond reproach: "a reputation of gallantry before I could usefully declare my principles." Indeed, his military service was far from grudging – he rose through the ranks to platoon commander and was awarded a Military Cross for single-handedly capturing a German machine gun nest and killing many of the enemy.

![]() Benjamin Britten was a different breed of pacifist – he not only refused to fight but rebuffed supporting the war effort through civilian activity.

Benjamin Britten was a different breed of pacifist – he not only refused to fight but rebuffed supporting the war effort through civilian activity.

Benjamin Britten c. 1960 |

In the words of Randall Swingler, which Britten had set in his 1939 Ballad of Heroes: "They were men who hated death and loved life. … Men who wished to create and not to destroy, / But knew the time must come to destroy the destroyer … / To fight for peace, for liberty and for you.")

In the words of Randall Swingler, which Britten had set in his 1939 Ballad of Heroes: "They were men who hated death and loved life. … Men who wished to create and not to destroy, / But knew the time must come to destroy the destroyer … / To fight for peace, for liberty and for you.")

Prior to the War, after completing his scholarship at the Royal Academy of Music, Britten expanded the scope of his practical knowledge by working at the General Post Office Film Unit, where he produced background soundtrack music for a wide variety of moods and (due as much to budgetary constraints as esthetic choice) for diverse small musical ensembles. But after resuming British residency, he hit his stride (and overcame scorn of his patriotism) in 1945 with Peter Grimes, an astounding triumph credited with nothing short of reviving English opera from a ten-generation slump following Henry Purcell (1659 – 1695). Although much of the praise centered upon Britten's diversified sources, musical invention and feeling for text, the complexity of the main character (both brute and poet) and subtext of social critique (townsfolk hounding a social outsider to his death) undoubtedly emboldened Britten to challenge cherished norms in further work. Overall, he achieved a reputation for sensitivity, both in setting the English language to music (as evidenced by numerous song cycles and operas), as well as efficient orchestration (as best known from his 1945 Young Person's Guide to the Orchestra, in which a theme – notably by Purcell – winds its way through all the major instruments, highlighting their character). Britten's growing renown as a skilled, eclectic vocal composer, fortified by his staunch pacifism, provided an apt foundation for the work most often cited as his masterpiece.

![]() In 1940

In 1940  Britten had written a 20-minute instrumental Sinfonia da requiem dedicated to the memory of his parents, in which a rowdy Dies irae "Dance of Death" is prefaced by the surging anxiety of a Lachrymosa and followed by a beatific Requiem eternam. Philip Ramey points out that, despite its title, the Sinfonia da Requiem has little relationship to either a symphony or a requiem, but rather wordlessly invokes the atmosphere of the Mass rather than its forms. He also notes the irony of it having been commissioned from an ardent pacifist by the Japanese government, which was waging war with China, although Herbert Reid asserts that the commission was received through a British intermediary on behalf of a vaguely-identified foreign ruler, and so Britten might not have been aware of the true sponsor (thus echoing the genesis of Mozart's Requiem). (Ultimately, and undoubtedly to Britten's great relief, the Emperor rejected the Sinfonia, ostensibly due to its Christian ideology and melancholy tone, "so very different from the anticipation of the [planning] Committee which had hoped to receive from a friendly nation felicitations expressed in musical form on the 2,600th anniversary of the founding of the Japanese Empire.") In any event, Reid suggests that Britten accepted the commission with the intention of finding some way to speak his conscience through his music and wound up fashioning the work as expressing a plea for peace (albeit a wholly non-verbal one). Indeed, at the time Britten stated that he was making the Sinfonia as anti-war as possible even though he doubted that social or political theories could be expressed in music, even while allowing that certain ideas could be suggested by combining new music with well-known musical phrases. His War Requiem not only follows that approach but represents a significant break from the vast bulk of prior classical music that glorified war and heroism. By way of example, focusing just on Britain in the early 20th century, consider Edward Elgar's 1917 Spirit of England which celebrates with uplifting energy and a stirring climax those "fallen in the cause of the free": "They went with songs to the battle, they were young, / Straight of limb, true of eye, steady and aglow. … / They laughed, they sang their melodies of England, / They fell open-eyed and unafraid."

Britten had written a 20-minute instrumental Sinfonia da requiem dedicated to the memory of his parents, in which a rowdy Dies irae "Dance of Death" is prefaced by the surging anxiety of a Lachrymosa and followed by a beatific Requiem eternam. Philip Ramey points out that, despite its title, the Sinfonia da Requiem has little relationship to either a symphony or a requiem, but rather wordlessly invokes the atmosphere of the Mass rather than its forms. He also notes the irony of it having been commissioned from an ardent pacifist by the Japanese government, which was waging war with China, although Herbert Reid asserts that the commission was received through a British intermediary on behalf of a vaguely-identified foreign ruler, and so Britten might not have been aware of the true sponsor (thus echoing the genesis of Mozart's Requiem). (Ultimately, and undoubtedly to Britten's great relief, the Emperor rejected the Sinfonia, ostensibly due to its Christian ideology and melancholy tone, "so very different from the anticipation of the [planning] Committee which had hoped to receive from a friendly nation felicitations expressed in musical form on the 2,600th anniversary of the founding of the Japanese Empire.") In any event, Reid suggests that Britten accepted the commission with the intention of finding some way to speak his conscience through his music and wound up fashioning the work as expressing a plea for peace (albeit a wholly non-verbal one). Indeed, at the time Britten stated that he was making the Sinfonia as anti-war as possible even though he doubted that social or political theories could be expressed in music, even while allowing that certain ideas could be suggested by combining new music with well-known musical phrases. His War Requiem not only follows that approach but represents a significant break from the vast bulk of prior classical music that glorified war and heroism. By way of example, focusing just on Britain in the early 20th century, consider Edward Elgar's 1917 Spirit of England which celebrates with uplifting energy and a stirring climax those "fallen in the cause of the free": "They went with songs to the battle, they were young, / Straight of limb, true of eye, steady and aglow. … / They laughed, they sang their melodies of England, / They fell open-eyed and unafraid."  And although in the finale of his 1929 choral symphony Morning Heroes Arthur Bliss included an Owen poem over a somber background of three tympani evoking distant artillery fire, it was dryly declaimed rather than sung and the overall mood is more one of reflection than censure.

And although in the finale of his 1929 choral symphony Morning Heroes Arthur Bliss included an Owen poem over a somber background of three tympani evoking distant artillery fire, it was dryly declaimed rather than sung and the overall mood is more one of reflection than censure.

Two earlier Britten vocal works reflected an ambivalent attitude toward war. His 1936 song cycle Our Hunting Fathers comprised seemingly incongruent movements addressing the extermination of rats, a dance of death ostensibly depicting falconry, and a woman mourning the death of her pet monkey. Its pacifist overtones arose mainly from the suggestion of some analogy broader than the time-honored tradition of the title. Beyond that, Philip Brett sees its unusual combination of high drama and biting irony within a modern eclectic score as a parable for the worsening political situation. Lloyd Moore goes further by asserting that Britten, well aware of the gathering storm, fashioned a contemporary allegory by including references to "German" and "Jew" and thus "signif[ying] unambiguously who is the hunter and who is the hunted." On the other hand, in his 1939 Ballad of Heroes Britten unabashedly saluted the bravery of the fallen of the Spanish Civil War with rousing, militant music and stirring poems (by W. H. Auden and Randall Swingler).  Even so, Eric Roseberry hears in the angry orchestral outbursts, off-stage musicians and a finale in which a tenor soloist and chorus sing different texts "a glimpse of things to come" in the structural elements that would inform the War Requiem.

Even so, Eric Roseberry hears in the angry orchestral outbursts, off-stage musicians and a finale in which a tenor soloist and chorus sing different texts "a glimpse of things to come" in the structural elements that would inform the War Requiem.

As for the War Requiem, Britten stated his intention rather diffidently: "I hope it will make people think a bit." Arthur D. Colman expands the goal: "His aim in this piece is first and foremost to deliver an interpretation to the world about the pain and betrayal of a century and the complicity of nations, religious institutions and ourselves in the loss of life and hope that ensued." In that light, the War Requiem could be said to have paved the way to the disillusionment and artistic protests of the Vietnam era. Perhaps its most immediate offspring was Stephen Schwartz and Leonard Bernstein's 1971 Mass, which took the concept of heterogeneity many steps further. A self-described theater piece, its abrasion against tradition was blatant and consciously eclectic, interjecting marches, meditations, opera arias, Broadway-style songs, blues, hymns, narration, scat, Hebrew prayers, gospel, folk, rounds, electronic dissonance, improvisation and even a kazoo chorus into the traditional text (which itself is set in a decidedly untraditional, and often discordant, manner), and culminates with an operatic mad scene in which a Celebrant rejects ritual garb and smashes sacraments in order to become free to "sing God a simple song" – a highly catholic, if not Catholic, work which some condemned as blasphemous but that clearly was intended to question the relevance of time-honored liturgy and its ability to cope with modern social issues.

![]() Coventry Cathedral (actually a large parish church) had stood for a half-millennium until destroyed along with its entire town by intensive Luftwaffe bombing in September 1940. (Although many historians discredit the claim, others contend that a top-secret British signal intelligence unit had learned of the raid, which ultimately killed over 500 civilians, but had to refrain from evacuation or mounting a defense to avoid alerting the Nazis that the Allies had broken their code.) In 1958 a modern replacement was nearing completion next to the ruins. The symbolism of their retention has impelled many interpretations, among them: a reminder of the cost of war (Philip Reed), the power of the Church, as a bastion of faith and forgiveness, to guard against the destruction of civilization (Young), or man's contrition before God for the sin of going to war (Mann). Britten was given an unrestricted commission to write a major choral work – sacred or secular – for its consecration. (Britten rejected the suggestion that he donate his work, asserting that he should be paid just as any other craftsman.)

Coventry Cathedral (actually a large parish church) had stood for a half-millennium until destroyed along with its entire town by intensive Luftwaffe bombing in September 1940. (Although many historians discredit the claim, others contend that a top-secret British signal intelligence unit had learned of the raid, which ultimately killed over 500 civilians, but had to refrain from evacuation or mounting a defense to avoid alerting the Nazis that the Allies had broken their code.) In 1958 a modern replacement was nearing completion next to the ruins. The symbolism of their retention has impelled many interpretations, among them: a reminder of the cost of war (Philip Reed), the power of the Church, as a bastion of faith and forgiveness, to guard against the destruction of civilization (Young), or man's contrition before God for the sin of going to war (Mann). Britten was given an unrestricted commission to write a major choral work – sacred or secular – for its consecration. (Britten rejected the suggestion that he donate his work, asserting that he should be paid just as any other craftsman.)  It is unclear when Britten seized upon the notion of incorporating Owen's poems, but he clearly was attracted by the poet's antiwar outlook and direct style (although he did make minor edits in the originals to better fit his music). A primary prototype for his concept was the Bach passion settings which punctuated Biblical verse with interpretive commentary. The strongest musical parallel was with Verdi's Missa da Requiem – beyond their overall theatricality, Mervyn Cooke notes that their respective Dies Irae movements are both in g-minor, create expectancy through rests between syllables, depict dread with prominent off-beat drumstrokes, and recapitulate their main Dies Irae themes to interrupt the concluding Libera me. Britten frankly acknowledged his models: "I think that I would be a fool if I didn't take notice of how … whoever you like to name had written their Masses. … If I have not absorbed that, that's too bad." Michael Steinberg suggests that this was not for want of originality but rather to establish connections with a great tradition (perhaps, it might be added, much as current rap artists "sample" the work of their predecessors, not as theft, as most courts assume, but rather in sincere tribute to respected forerunners). Colman goes further: "He wanted the largest possible context for this pacifist work, and he wanted a hand in destroying, or at least subverting, the institutions that preserved war. He chose the Church and its great musical form to represent all the sanctified institutions which allow the Nations to send sons off to die. To do this, he went directly to the heart of the beast and challenged Christianity's ancient and sacred celebration of life after death: the Mass for the Dead."

It is unclear when Britten seized upon the notion of incorporating Owen's poems, but he clearly was attracted by the poet's antiwar outlook and direct style (although he did make minor edits in the originals to better fit his music). A primary prototype for his concept was the Bach passion settings which punctuated Biblical verse with interpretive commentary. The strongest musical parallel was with Verdi's Missa da Requiem – beyond their overall theatricality, Mervyn Cooke notes that their respective Dies Irae movements are both in g-minor, create expectancy through rests between syllables, depict dread with prominent off-beat drumstrokes, and recapitulate their main Dies Irae themes to interrupt the concluding Libera me. Britten frankly acknowledged his models: "I think that I would be a fool if I didn't take notice of how … whoever you like to name had written their Masses. … If I have not absorbed that, that's too bad." Michael Steinberg suggests that this was not for want of originality but rather to establish connections with a great tradition (perhaps, it might be added, much as current rap artists "sample" the work of their predecessors, not as theft, as most courts assume, but rather in sincere tribute to respected forerunners). Colman goes further: "He wanted the largest possible context for this pacifist work, and he wanted a hand in destroying, or at least subverting, the institutions that preserved war. He chose the Church and its great musical form to represent all the sanctified institutions which allow the Nations to send sons off to die. To do this, he went directly to the heart of the beast and challenged Christianity's ancient and sacred celebration of life after death: the Mass for the Dead."  As further inspiration Neil Powell cites Michael Tippett's 1941 A Child of Our Time, which interjected five spirituals into the composer's own text tracing the events and effect of the Nazi Kristallnacht pogroms. Britten also expressed esteem for Mahler's orchestral technique and sense of compositional irony, and claimed particular affection for Mahler's Eighth Symphony which comprises the disparate texts of a Latin hymn and the closing scene of Goethe's Faust. (Britten had cited Mahler's Eighth in 1943 as his favorite work, and possibly took further inspiration for the War Requiem from the collossal forces required to perform that so-called "Symphony of a Thousand").

As further inspiration Neil Powell cites Michael Tippett's 1941 A Child of Our Time, which interjected five spirituals into the composer's own text tracing the events and effect of the Nazi Kristallnacht pogroms. Britten also expressed esteem for Mahler's orchestral technique and sense of compositional irony, and claimed particular affection for Mahler's Eighth Symphony which comprises the disparate texts of a Latin hymn and the closing scene of Goethe's Faust. (Britten had cited Mahler's Eighth in 1943 as his favorite work, and possibly took further inspiration for the War Requiem from the collossal forces required to perform that so-called "Symphony of a Thousand").

Britten began writing the War Requiem in the summer of 1960 and completed it on December 20, 1961, a year that Steinberg notes had been especially anxious with the Bay of Pigs invasion, construction of the Berlin Wall and escalation of U.S. involvement in Vietnam. Britten prefaced his score with a quotation from Owen's foreword to an unrealized collection of his poems that he intended to present as a panorama of modern war, exposing its true nature and its impacts on soldiers, civilians and society at large:

My subject is War, and the pity of War.White explains that to Owen: "pity" meant not the feeling of sorrow and regret that we usually associate with the word but rather the truth and power of emotion that poetry can invoke; war was a microcosm and symbol of the universal tragedy of life; and his poems were intended as a protest against war's reversal of values that mankind should endeavor to uphold. Plomer adds that Owen's "pity" extended to the imagination of the deceased who could no longer speak to future generations. Britten dedicated the score to "all the Fellow-Sufferers of the Second World War, & in loving memory" of three friends who had died in combat and a fourth who had survived and remained in the military for a decade but was unable to transition to civilian life and killed himself.

The Poetry is in the pity.

All a poet can do today is warn.

(Reed notes that out of sensitivity to reproach over his conscientious objector status, Britten excised the reference to "Fellow-Sufferers" prior to publication.)

(Reed notes that out of sensitivity to reproach over his conscientious objector status, Britten excised the reference to "Fellow-Sufferers" prior to publication.)

In his commentary to the premiere recording, John Culshaw describes Britten's structural conception as one of conflict among three distinct planes: a soprano soloist, full chorus and orchestra intoning the traditional Latin text as a formal expression of mourning and a plea for deliverance; a chamber ensemble and tenor and baritone soloists singing nine Owen poems as a personal vision here and now; and an organ and boys' choir (concealed and distant) conveying the mystery of innocence. (And just to get it out of the way, while Owen may have been discreetly gay, and while Britten was homosexual and attracted to boys, there has never been any suggestion that either ever acted inappropriately; indeed, by all accounts Britten was a devoted mentor who treated boys with genuine, platonic affection.) The three musical planes are kept distinct until merging at the very end in a tenuous reconciliation (challenged by dissonant, unstable tritones, which form a central motif of the overall musical setting). Beyond the explicit contrasts between ancient Latin vs. modern English, the generality of prayer vs. specific challenges of life, or public commemoration vs. personal experience, Arnold Whittall hears the War Requiem as reflecting Britten and Owen's shared doubts about the failure of religion to condemn war, and its juxtapositions, tensions and unstable structure as reflecting a more potent metaphor than a mere explicit denunciation of violence.

The relationships between the Owen poems and the traditional Mass vary considerably within the six movements of the War Requiem:

- I – Requiem aeternam ~ The prayer for eternal rest and divine mercy is challenged by Owen's "Anthem for Doomed Youth" which laments the futility of mourning the adolescent victims of battle ("What passing-bells for those who die as cattle?")

- II – Dies irae ~ The opening rousing trumpet call to judgment is answered by an untitled poem of sorrowful bugles calming boys facing "the shadow of the morrow." The judgment itself chafes against "The Next War," which mockingly salutes death as a friend and chillingly looks to a future "when each proud fighter brags / He wars on Death – for life; not men – for flags." The ensuing prayer for forgiveness leads to an adverse wish for a huge cannon: "Great gun towering toward Heaven, about to curse; / May God curse thee and cut thee from our soul." The concluding section, looking toward resurrection, is answered by "Futility" in which the life-giving sun cannot revive a newly-fallen soldier ("Move him into the sun – … Full-nerved – still warm – too hard to stir? / Was it for this the clay grew tall?").

- III – Offeratorium ~ The prayer to rescue the faithful from hell into light, in fulfillment of God's promise to Abraham, clashes against "The Parable of the Old Man and the Young," in which the binding of Isaac is retold with a far different outcome: when offered the ram as a substitute sacrifice, "the old man would not do so, but slew his son, – / And half the seed of Europe, one by one."

- IV – Sanctus ~ Praise of God and divine omnipresence clashes with "The End" in which Time, Age and the Earth ache over the permanence of death: "Mine ancient scars shall not be glorified, / Nor my titanic tears, the sea, be dried."

- V – Agnus Dei ~ The prayer for the Lamb of God to take away the sins of the world and grant rest is interspersed with verses of "At a Calvary near the Ancre," in which Christ is wounded in battle and proclaims Owen's own pacifist belief: "The scribes on all the people shove / And bawl allegiance to the state, / But they who love the greater love / Lay down their life; they do not hate."

- VI – Libera me ~ Halves of the concluding prayer for personal freedom from death and for eternal rest bracket "Strange Meeting," a surrealistic encounter of two former foes ("I am the enemy you killed, my friend") who bemoan the life that will no longer be. As all the other voices combine to conclude with the consoling "Requiescant in pace" ("May they rest in peace") the two male soloists keep repeating ever more softly "Let us sleep now," as the bittersweet music fades and dissonant bells deny from afar any hope for genuine repose or comfort, a worthy echo and legacy of the precedents of Beethoven and Verdi.

While the foregoing focuses on (and unfairly simplifies) the text, Britten's music transcends mere accompaniment to serve an equal, if not leading, role in the overall impact, but any meaningful analysis would vastly exceed the scope of this article (and my proficiency). The liner notes to most of the War Requiem recordings provide some guidance, and detailed exploration is found in Colman's study (emphasizing emotional connotations) and Cooke's Cambridge Music Handbook (detailing the technical specifics). Even so, the music ranges from haunting motifs (as in the opening) and the medieval sound of the boys' choir to overseas gamelan sonorities and an extraordinary modern Sanctus passage where "the full chorus, divided into eight parts, gradually enters [with] unsynchronized chanting" in which "all twelve pitches have been sounded in a chromatic totality graphically representing the text 'Pleni sunt coeli et terra gloria tua' ('Heaven and earth are full of thy glory')" (Cooke). Throughout, the score displays the economy, clarity and mastery of instrumental coloring that Young attributes to Britten's esteem for Stravinsky. It seems fair to say that Britten generally lavishes his melodies on the traditional choral sections rather than on the settings of Owen's poems so as not to distract from the import of their compelling words. In that regard it is worth noting, as Benjamin Lee points out, that in setting the texts Britten "often felt that traditional accentuation ... contradicted stress patterns demanded by emotional content," and so his vocal lines are full of unnatural emphases that can sound awkward and even forced when compared to the smooth articulation to which we are accustomed in traditional song but which are intended here to impel consideration of the deeper meaning.

![]() In order to emphasize the universal desire for peace, for the premiere Britten seized upon the symbolism of assigning the solos to artistic delegates of former (English and German) and current (Russian) enemies, who had suffered the most in World War II.

In order to emphasize the universal desire for peace, for the premiere Britten seized upon the symbolism of assigning the solos to artistic delegates of former (English and German) and current (Russian) enemies, who had suffered the most in World War II.

The intended original cast: Fischer-Dieskau, Pears, Vishnevskaya |

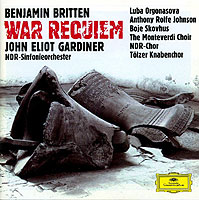

Critical reaction was mostly ecstatic.  Cooke proclaimed: "It is difficult to call to mind any other major 20th century work which met with such instantaneous and unanimously high praise from almost all sectors of the media." Others wrote that it: "makes criticism impertinent," "stirred musical sensibilities in this country more powerfully than has any new work within recent memory" and "deserves to be heard and absorbed and pondered by everyone with a stake in the future." Pears had to aid Fischer-Dieskau, who nearly collapsed with emotion: "The first performance created an atmosphere of such intensity that by the end I was completely undone; I did not know where to hide my face." Others, though, tempered their enthusiasm. Philip Brett called it pretentious and grandiloquent and questioned "the application of a World War I pacifist message in a post-World War II context," citing in particular its silence about nuclear disarmament that was so germane to the early 1960s and the Holocaust. Brett went on to attribute the use of Owen's poetry to an expression of Britten's homosexual politics and his "anger about the fate of young men sent to their deaths by an unfeeling patriarchal system," although he admits that "possibly a metaphorical extension can be made to all innocent victims." Desmond Shawe-Taylor noted that its impact was magnified by arriving at a time of artistic scarcity when new masterworks were rare, and Joan Chissell and Igor Stravinsky both wondered if the message and critical hype eclipsed the music. In that regard Lee asserts: "It was difficult to separate the music from its subject matter, and who would be willing to be caught in a negative stance against a work decrying war in favor of peace?" Indeed, several critics dubbed it a masterwork before ever having heard it. Even so, the War Requiem quickly assumed iconic resonance; Cooke notes that further performances were especially greeted in countries most touched by war and it assumed symbolic import to perpetuate memories, honor sites and commemorate occasions of exceptional significance in the course of 20th century warfare. (The cover of the acclaimed 1992 Gardiner/NDR DG CD set shows the bells, preserved as they had fallen in wartime bombing, outside the Marienkirche in Lübeck, where the live concert recording took place.) Critical polemic aside, the War Requiem undoubtedly is the most celebrated oratorio of the 20th century.

Cooke proclaimed: "It is difficult to call to mind any other major 20th century work which met with such instantaneous and unanimously high praise from almost all sectors of the media." Others wrote that it: "makes criticism impertinent," "stirred musical sensibilities in this country more powerfully than has any new work within recent memory" and "deserves to be heard and absorbed and pondered by everyone with a stake in the future." Pears had to aid Fischer-Dieskau, who nearly collapsed with emotion: "The first performance created an atmosphere of such intensity that by the end I was completely undone; I did not know where to hide my face." Others, though, tempered their enthusiasm. Philip Brett called it pretentious and grandiloquent and questioned "the application of a World War I pacifist message in a post-World War II context," citing in particular its silence about nuclear disarmament that was so germane to the early 1960s and the Holocaust. Brett went on to attribute the use of Owen's poetry to an expression of Britten's homosexual politics and his "anger about the fate of young men sent to their deaths by an unfeeling patriarchal system," although he admits that "possibly a metaphorical extension can be made to all innocent victims." Desmond Shawe-Taylor noted that its impact was magnified by arriving at a time of artistic scarcity when new masterworks were rare, and Joan Chissell and Igor Stravinsky both wondered if the message and critical hype eclipsed the music. In that regard Lee asserts: "It was difficult to separate the music from its subject matter, and who would be willing to be caught in a negative stance against a work decrying war in favor of peace?" Indeed, several critics dubbed it a masterwork before ever having heard it. Even so, the War Requiem quickly assumed iconic resonance; Cooke notes that further performances were especially greeted in countries most touched by war and it assumed symbolic import to perpetuate memories, honor sites and commemorate occasions of exceptional significance in the course of 20th century warfare. (The cover of the acclaimed 1992 Gardiner/NDR DG CD set shows the bells, preserved as they had fallen in wartime bombing, outside the Marienkirche in Lübeck, where the live concert recording took place.) Critical polemic aside, the War Requiem undoubtedly is the most celebrated oratorio of the 20th century.

![]() Having come to know the War Requiem only through recordings, I was eager to heed the oft-stated admonition that its full import could only emerge in its intended public setting and so I recently welcomed the opportunity when it was given at the Washington, DC Kennedy Center under our new music director, Gianandrea Noseda. Yet despite the excellence of the performance I was surprisingly unmoved. Even aside from my annoying neighbors – the lady so absorbed in reading her program that she rarely looked up (why not save $$$ and just buy a CD?) and the gentleman whose nasal issues seemed timed to erupt in the quietest sections – I found myself more engrossed in the mechanics of execution than transported on an indelible emotional journey. I'm sure that says far more about my attention span than Britten's genius, and yet it fortifies my conviction that the subtleties of this extraordinary work are well suited to be heard in private, free from audience distractions.

Having come to know the War Requiem only through recordings, I was eager to heed the oft-stated admonition that its full import could only emerge in its intended public setting and so I recently welcomed the opportunity when it was given at the Washington, DC Kennedy Center under our new music director, Gianandrea Noseda. Yet despite the excellence of the performance I was surprisingly unmoved. Even aside from my annoying neighbors – the lady so absorbed in reading her program that she rarely looked up (why not save $$$ and just buy a CD?) and the gentleman whose nasal issues seemed timed to erupt in the quietest sections – I found myself more engrossed in the mechanics of execution than transported on an indelible emotional journey. I'm sure that says far more about my attention span than Britten's genius, and yet it fortifies my conviction that the subtleties of this extraordinary work are well suited to be heard in private, free from audience distractions.

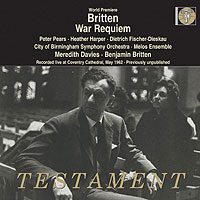

Peter Pears, Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, Heather Harper; Coventry Festival Choir, Boys of Holy Trinity, Leamington, and Holy Trinity, Stratford; City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra conducted by Meredith Davies; Melos Ensemble conducted by Benjamin Britten (May 30, 1962; Testament CD)

This is the BCC broadcast of the premiere, suppressed until finally released as a Testament CD in 2013.  John Culshaw's notes to the ensuing studio recording reflect the conventional wisdom: "Although the occasion was a great one, the musical result did something less than justice to the work, and the BBC transcription provides pretty strong evidence against those critics who still insist upon the sanctity of live performances transferred to disc. No amount of talk about 'atmosphere' will alter the fact that a great deal went awry in Coventry that night. ... That the War Requiem survived such a series of … mishaps is a tribute to its resilience." Upon the Testament release critics were able to confirm the lapses: missed entrances, scrappy orchestral playing, ragged choral work, strange balances, compressed dynamics and muffled, congested sound. Yet there was universal praise for the soloists – Ben Hogwood called the men "a fearsome team" and Paul Fairman found Heather Harper "at her peak, all gleaming beauty and commanding authority." Above all, it was agreed that the sense of a hugely momentous occasion persisted after a half-century. Heard today, all the blemishes are evident and yet seem "largely incidental to the intensity of this incisive performance" that "crackles with atmosphere, like the passing of an electrical storm" (Hogwood); indeed it takes no great stretch of imagination to "feel the genuine emotion" (Richard Ginell) in all its "messy glory" (Fairman). Even so, far too much is lost in the sonic sludge (closer to AM quality than FM) to convey the score's exquisite detail.

John Culshaw's notes to the ensuing studio recording reflect the conventional wisdom: "Although the occasion was a great one, the musical result did something less than justice to the work, and the BBC transcription provides pretty strong evidence against those critics who still insist upon the sanctity of live performances transferred to disc. No amount of talk about 'atmosphere' will alter the fact that a great deal went awry in Coventry that night. ... That the War Requiem survived such a series of … mishaps is a tribute to its resilience." Upon the Testament release critics were able to confirm the lapses: missed entrances, scrappy orchestral playing, ragged choral work, strange balances, compressed dynamics and muffled, congested sound. Yet there was universal praise for the soloists – Ben Hogwood called the men "a fearsome team" and Paul Fairman found Heather Harper "at her peak, all gleaming beauty and commanding authority." Above all, it was agreed that the sense of a hugely momentous occasion persisted after a half-century. Heard today, all the blemishes are evident and yet seem "largely incidental to the intensity of this incisive performance" that "crackles with atmosphere, like the passing of an electrical storm" (Hogwood); indeed it takes no great stretch of imagination to "feel the genuine emotion" (Richard Ginell) in all its "messy glory" (Fairman). Even so, far too much is lost in the sonic sludge (closer to AM quality than FM) to convey the score's exquisite detail.

An intriguing supplement is a filmed August 4, 1964 Royal Albert Hall Proms concert (hence the anomaly of formally-dressed performers and strikingly casual audience), now readily available online. Co-conducted by Britten and Davies with the Melos Ensemble, Pears and Harper (but now with baritone Thomas Hemsley and the superior BBC Symphony Orchestra and Chorus), it largely replicates the performers and rendition of the premiere while adding an intensely human dimension to the aural record of history. Britten intended it to be "a really authoritative record of how we like it to go and what it is all about." The date was significant, marking the 50th anniversary of the outbreak of World War I. Although in the July 27, 1963 American premiere in Boston, available on a VAI DVD, the choirs were bracketed by the instrumentalists, here in a standard array the choruses are spread out behind the orchestra, with the chamber ensemble and soloists in front of the cellos and the boys' choir in a high recessed alcove. Davies's broad gestures and expressive physicality provide an intriguing contrast with Britten's precise cues. (Admittedly, Britten guides the less demanding forces and sections; in a mark of extreme confidence, often he doesn't bother to beat the time but simply indicates entrances.) Pears visibly caresses each syllable of his part with exquisite devotion. The shots are well-planned and the editing unobtrusive, with long takes, majestic slow pans and leisurely outward zooms. The sound is decent mono and the optics are good 16mm quality. Alas, an announcer spoils the continuity with gratuitous introductions to all but the Agnus Dei movement. Overall it's a valuable document, affording an opportunity to visualize the creative forces behind the premiere.

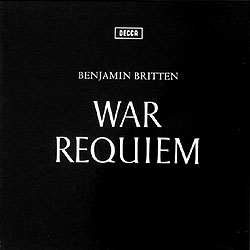

Peter Pears, Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau, Galina Vishnevskaya; Bach Choir and London Symphony Orchestra Chorus, Highgate School Choir; London Symphony Orchestra and Melos Ensemble conducted by Benjamin Britten (Decca LP set, 1963; CD reissues, 1985 and 1999)

For the first recording, undertaken in the superior acoustics of Kingsway Hall over six sessions in early January 1963, Britten assembled his originally-intended soloists and the Melos Ensemble but now used an orchestra and choruses of recognized excellence.  Britten himself served as the sole conductor. Released in May with an ascetic cover that proclaimed its solemnity, the two-record boxed set was a phenomenal success, topping international classical charts and selling nearly a quarter-million copies by the end of the year. In greeting its first CD transfer over two decades later, Edward Greenfield in Gramophone pronounced it: "among the most magnetic performances of British music ever put on record" and "one which will never be superseded." Reviewing a 1998 CD reissue, John Quinn summed up its enduring virtues – even beyond the authoritative insight of Britten and his soloists, "all the performers respond with evident and complete commitment, … the playing of the LSO is magnificently incisive … and are recorded with tremendous presence, … the Melos Ensemble accompanies the male soloists with great sensitivity and no little virtuosity, … [the chorus] sing superbly and meet all of Britten's stringent demands concerning dynamics, [and] the boys … sing with an innocent purity and great accuracy." A superb achievement of both execution and technology, it remains the touchstone against which all subsequent War Requiem recordings are still measured.

Britten himself served as the sole conductor. Released in May with an ascetic cover that proclaimed its solemnity, the two-record boxed set was a phenomenal success, topping international classical charts and selling nearly a quarter-million copies by the end of the year. In greeting its first CD transfer over two decades later, Edward Greenfield in Gramophone pronounced it: "among the most magnetic performances of British music ever put on record" and "one which will never be superseded." Reviewing a 1998 CD reissue, John Quinn summed up its enduring virtues – even beyond the authoritative insight of Britten and his soloists, "all the performers respond with evident and complete commitment, … the playing of the LSO is magnificently incisive … and are recorded with tremendous presence, … the Melos Ensemble accompanies the male soloists with great sensitivity and no little virtuosity, … [the chorus] sing superbly and meet all of Britten's stringent demands concerning dynamics, [and] the boys … sing with an innocent purity and great accuracy." A superb achievement of both execution and technology, it remains the touchstone against which all subsequent War Requiem recordings are still measured.

Producer John Culshaw enhanced the impact by capturing the varied textures in a convincing stereo spread.

John Culshaw with Britten |

The 1999 CD reissue includes a fascinating bonus – 50 minutes of rehearsals that Culshaw had covertly taped and then presented to Britten as a special LP for a 50th birthday gift. (Alas, Britten spurned it as an invasion of his privacy.) Yet even if the excerpts might have been edited to excise less flattering bits, they present a wholly admirable portrait of Britten as a conductor – consistently patient, polite, encouraging and complimentary, with even occasional humor (admitting "the composer was right" after trying and rejecting his own alternative interpretive suggestion; admonishing the boys' choir to not "make it sound nice – it's modern music!"), while providing precise and detailed directions for articulation, dynamics and even intangible feelings (asking the chorus to produce a "floating sound, like coming out of a dream"). Clearly Britten knew just what he wanted – and how to communicate and realize it, all the more reason to regard his recording as thoroughly idiomatic if not definitive.

But that very factor could be perceived as an obstacle.  In a Gramophone review of the Giulini concert recording, David Hurwitz contended: "A composer's own recorded interpretation of his work casts a pall on future versions, both live and on disc. … In Britten's case the problem is particularly acute because … he was a superb conductor." Hurwitz further notes that others were discouraged from an appreciably different approach out of respect for Britten and especially when, as in several later recordings, the composer participated directly by leading the chamber ensemble. The problem was compounded when Peter Pears often appeared as the tenor soloist, as he was recognized as far more than a mere performer, but rather the artistic collaborator, intimate soul-mate and foremost interpreter of Britten, who wrote the part (and most of the leading male roles in his operas) expressly with Pears's voice and expression in mind. Hurwitz adds that the sheer complexity of executing a performance of the War Requiem leaves little occasion for a conductor to interpret it. The net result was to dampen temptation to depart significantly from the model Britten had documented through his brilliant creator's recording.

In a Gramophone review of the Giulini concert recording, David Hurwitz contended: "A composer's own recorded interpretation of his work casts a pall on future versions, both live and on disc. … In Britten's case the problem is particularly acute because … he was a superb conductor." Hurwitz further notes that others were discouraged from an appreciably different approach out of respect for Britten and especially when, as in several later recordings, the composer participated directly by leading the chamber ensemble. The problem was compounded when Peter Pears often appeared as the tenor soloist, as he was recognized as far more than a mere performer, but rather the artistic collaborator, intimate soul-mate and foremost interpreter of Britten, who wrote the part (and most of the leading male roles in his operas) expressly with Pears's voice and expression in mind. Hurwitz adds that the sheer complexity of executing a performance of the War Requiem leaves little occasion for a conductor to interpret it. The net result was to dampen temptation to depart significantly from the model Britten had documented through his brilliant creator's recording.

So persistent was Britten's influence that no further studio recording was attempted until 1983, seven years after his death. Even so, several earlier concerts have since been released (Leinsdorf/Boston, the 1963 American premiere, VAI DVD; Ancerl/Czech Philharmonic, 1966, Supraphon CD; Ansermet/Suisse Romande, 1967, BSR CD; Giulini/New Philharmonia, 1969, BBC Legends CD). Of these, the last fit on a single mid-priced CD and has been cited as the most distinctive – Giulini was Britten's second choice for the premiere, Britten co-conducts, Pears sings, the pacing is swift and, despite dynamic compression, some tape drop-outs and the inevitable flaws of any live presentation, the recording is unexpectedly clear within the notorious muddy echo of the mammoth Royal Albert Hall.

Robert Tear, Thomas Allen, Elisabeth Söderström; City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra and Chorus, Boys of Christ Church Cathedral, Oxford; Simon Rattle conducting (EMI, 1983)

Two full decades after Britten's own triumphant recording came this first competing one.  Although at the premiere Britten had slammed the Birmingham chorus as "deplorable" and Ginell knocked its orchestra as "just a provincial ensemble," three years into his tenure as their Principal Conductor Rattle had already elevated them to international status. Made digitally but released on both LP and CD, their War Requiem managed to avoid much of the harshness that plagued early digital productions while drawing plaudits for its quiet background and wide dynamics (which, as many have observed, commonly tend to be wider on disc than in the concert hall).

Although at the premiere Britten had slammed the Birmingham chorus as "deplorable" and Ginell knocked its orchestra as "just a provincial ensemble," three years into his tenure as their Principal Conductor Rattle had already elevated them to international status. Made digitally but released on both LP and CD, their War Requiem managed to avoid much of the harshness that plagued early digital productions while drawing plaudits for its quiet background and wide dynamics (which, as many have observed, commonly tend to be wider on disc than in the concert hall).

Nearly all reviews of subsequent recordings invariably remark on their essential similarity to Britten's, and few point out any significant distinctions beyond minor tempo variations, the soloists' personas and improvements in recording technology. Yet the new production drew inevitable comparisons with its only competitor and consistent plaudits, perhaps in part simply because critics had been starved for an alternative. Thus in Stereo Review, Richard Freed praised all the performers, with the boys' choir "clearly more alert" than Britten's, and Rattle's leadership of "vitality and freshness" in "this beautiful and stirring performance" as more dramatic than Britten's comparative sobriety. Edward Greenfield in Gramophone largely agreed, concluding: "All in all, though no one is going to pass over the historic Britten recording, this new one blazes the message of this masterly work with a freshness to have one hearing it as though for the first time."

The timings of the two sets' movements are virtually identical and their impacts equally potent. Heard today, the most evident difference lies in the soloists. That, in turn, confronts a key issue: Britten wrote the War Requiem parts specifically for the qualities of his intended interpreters, so to what extent do others' divergent talents enrich or undermine Britten's plan? Thus Vishnevskaya had been criticized for inaccurate pitch and slack rhythm, but one could consider those to have been intentional reflections of intense emotion, and Söderström's injection of more warmth into her role could seem to quash an implicit critique of ritual as aloof and imperious. Pears's voice was reputed as distinctive, clear and commanding yet lacking color but that, too, could be seen as crucial to conveying Owen's dispassionate view of heartless sacrifice. Freed singled out Allen as "sounding a good deal more comfortable with the Wilfred Owen texts than Fischer-Dieskau," but perhaps a German's struggle to master and express a former enemy's language had purposeful symbolic overtones.  Beyond the soloists, Rattle's tendency to project a more blended sound than Britten's terse articulation prompts reflection of whether the War Requiem gains impact through Rattle's integration of human endeavor and foibles or by Britten's emphasizing a firm distinction between formal routine and harsh reality. For that matter, is Rattle's unleashing the full power of hundreds of voices and instruments through maximizing the dynamic extremes ultimately more compelling than Britten's comparative humbling restraint of the original artists' meager protest against the incorrigible evil of mankind?

Beyond the soloists, Rattle's tendency to project a more blended sound than Britten's terse articulation prompts reflection of whether the War Requiem gains impact through Rattle's integration of human endeavor and foibles or by Britten's emphasizing a firm distinction between formal routine and harsh reality. For that matter, is Rattle's unleashing the full power of hundreds of voices and instruments through maximizing the dynamic extremes ultimately more compelling than Britten's comparative humbling restraint of the original artists' meager protest against the incorrigible evil of mankind?

Writing in the Washington Post, Joseph McLellan credited Rattle with not "feeling constrained to slavish imitation," and ultimately serving to document the status of the War Requiem as a musical classic which "is, by definition, a work that can go on living and growing after it leaves the composer's hand." Part of the appeal of the Rattle recording (and others to follow) lay merely in being different and thus suggesting additional interpretive possibilities, subtle though they might turn out to be.

Having arrived at the digital era with the Rattle set, I gladly leave evaluations and comparisons among the nearly two dozen further recordings (so far!) to critics whose opinions are readily available on line. (By way of excuse for my hesitation to take that plunge – and as a caution to others – I do believe that much of the impact of the War Requiem lies in the surprise of encountering its unsettling structure which familiarity threatens to devalue, even though that same sense of comfort might operate to infer a unity of human experience.) That said, I note that the versions from Hickox/London Symphony (Chandos, 1992), Gardiner/NDR (DG, 1993), Noseda/London Symphony (LSO, 2011), McCreech/Gabrielli (Signum, 2013) and Pappano/Santa Cecilia (Warner, 2013) all have received highly enthusiastic reviews with which, having heard them, I concur. Each has abundant allures and will serve well as a complement to Britten's. If I had to choose just one, I suppose I'd opt for Pappano overall (plus it fits on a single CD) or Noseda for heightened drama, but I find myself in empathy with a guy who dates lots of women and claims as his favorite the one he saw last.

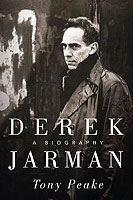

![]() While most devotees regard the score as self-sufficient if not sacrosanct, Derek Jarman used Britten's War Requiem as the basis for a provocative 1988 movie.

While most devotees regard the score as self-sufficient if not sacrosanct, Derek Jarman used Britten's War Requiem as the basis for a provocative 1988 movie.  Jarman was a multi-talented, militant gay rights advocate whose cinematic oeuvre evolved from the frank sexuality and obscure Latin dialog of Sebastiane (1976) and the seemingly random accumulation of frantic images and disparate scenes comprising a bitter cry of desperation in Last of England (1987) to the accessible linear biographical vignettes of Wittgenstein (1993, conceived theatrically, with lavish costumes and witty props shot against a black backdrop) and the daring discipline of his final film, Blue (1994), made as he was succumbing to AIDS and losing his eyesight, comprising a single 75-minute shot of a static solid blue screen that compels focus on the complex soundtrack, a deeply personal mix of music, poetry, sound effects and biographical reflections on medical ordeals and life, spawning a haunting, evocative meditation on mortality and memory. For those alienated by such creative audacity, Jarman's War Requiem imposes the structure of the Britten score, which was licensed on condition that the 1963 recording be presented intact and without any added text or even sound effects. Perhaps in part a cathartic response to his then-recent diagnosis, Jarman attenuates many of his wonted themes (homo-eroticism, social dissolution) and represses any hint of humor to focus on underscoring the sober anti-war footing of Owen's poetry.

Jarman was a multi-talented, militant gay rights advocate whose cinematic oeuvre evolved from the frank sexuality and obscure Latin dialog of Sebastiane (1976) and the seemingly random accumulation of frantic images and disparate scenes comprising a bitter cry of desperation in Last of England (1987) to the accessible linear biographical vignettes of Wittgenstein (1993, conceived theatrically, with lavish costumes and witty props shot against a black backdrop) and the daring discipline of his final film, Blue (1994), made as he was succumbing to AIDS and losing his eyesight, comprising a single 75-minute shot of a static solid blue screen that compels focus on the complex soundtrack, a deeply personal mix of music, poetry, sound effects and biographical reflections on medical ordeals and life, spawning a haunting, evocative meditation on mortality and memory. For those alienated by such creative audacity, Jarman's War Requiem imposes the structure of the Britten score, which was licensed on condition that the 1963 recording be presented intact and without any added text or even sound effects. Perhaps in part a cathartic response to his then-recent diagnosis, Jarman attenuates many of his wonted themes (homo-eroticism, social dissolution) and represses any hint of humor to focus on underscoring the sober anti-war footing of Owen's poetry.

The movie begins serenely enough as an aged veteran (Laurence Olivier in his final film role) recites off-screen over distant tolling bells the first half of "Strange Meeting" (including a handful of verses Britten omitted). Once the score begins, the visuals range from direct depiction (fictionalized scenes from Owen's childhood, military training and war experiences; a re-enactment in modern garb of Abraham's binding (and slaughter) of Isaac, applauded by lurid financiers; a montage of explosions during the final Dies irae [Day of wrath]) to trenchant if basic contrasts (passing out rifles while nurses lay out bandages; troops marching while a sheep is slaughtered), and seemingly obscure but presumably personally meaningful allusions (a pet funeral; lighting Christmas tree candles).  In a recurring motif, scenes of battle and hideous wounds careen among historical war footage and modern re-enactments, signifying the universality, and perhaps future inevitability, of war and its tragic aftermath. The most hauntingly effective scene is the simplest – opening the Sanctus with a six-minute tight shot of Tilda Swinton, cast as a nurse, dressed in a simple frock, listlessly braiding her hair and then smoothly effecting a catalog of emotional boundaries in a wordless litany of human feeling.

In a recurring motif, scenes of battle and hideous wounds careen among historical war footage and modern re-enactments, signifying the universality, and perhaps future inevitability, of war and its tragic aftermath. The most hauntingly effective scene is the simplest – opening the Sanctus with a six-minute tight shot of Tilda Swinton, cast as a nurse, dressed in a simple frock, listlessly braiding her hair and then smoothly effecting a catalog of emotional boundaries in a wordless litany of human feeling.

Critical reaction ran to extremes. Joseph McLellan in the Washington Post praised it as eloquent and complex, with "visual images that match the power of [the] music. … [It] must be taken seriously as a classic work of art. … Jarman has added visuals so intense that this is likely to be the ultimate embodiment of the idea until someone develops a technique for recording and playing back physical sensations other than sight and sound." Yet Bosley Crowther in the New York Times slammed it as: "epic irrelevance. …  The oratorio is upstaged by the mostly awful pictures on the screen" and "proceeds as a kind of free-association journey" with "the sort of baroque image that is utterly beside the point of the work of both Britten and Owen." (It seems ironic that Crowther, the movie critic, upheld the integrity of the music while McLellan, the music critic, did not.)

The oratorio is upstaged by the mostly awful pictures on the screen" and "proceeds as a kind of free-association journey" with "the sort of baroque image that is utterly beside the point of the work of both Britten and Owen." (It seems ironic that Crowther, the movie critic, upheld the integrity of the music while McLellan, the music critic, did not.)

Jarman justified his approach as the legitimate response of one artist to another (much as Britten had responded to Owen). Yet his movie does serve to raise a thoughtful point, to which Crowther alluded in his review: "No one connected to the filmed 'War Requiem' seems to have considered the possibility that oratorios are far more effective when heard than seen." While Jarman's images might be deeply involving in their own right and may add a level of meaning (and thus make the War Requiem more accessible to the video generation), something is lost by attaching specificity to purely aural art (the very point of distinction that McLellan had praised). Music by its very nature is abstract and thus invites each listener to apply one's own experience, personality and imagination to evoke individual reflection, conjure imagery and provide meaning. To impose specific interpretation, no matter how compelling, would seem to defeat the essential power of music – and, indeed, of poetry – to suggest rather than state. To accept one artist's visual rendering of music inevitably results in overlooking the limitless realm of other possibilities. (And such images can be exasperatingly durable – I still think of Fantasia dinosaurs when hearing Stravinsky's Rite of Spring.) Moreover music affects us in part by requiring us to internalize it, and thus to be active participants in a dynamic creative process. But by feeding us a procession of pre-selected images to which we become mere passive spectators, Jarman's War Requiem, like other music videos, excludes us from constructive activity and spares us from the challenge of supplying our own psychic energy in order to create personal meaning. The result cannot compare with the experience of listening thoughtfully to the music alone, especially given the unavoidable dominance of a movie's soundtrack by its visuals. That said, at least some of Jarman's images are sufficiently vague as to invite at least some level of prompting us to fashion a personal interpretation.

![]() Britten prefaced the War Requiem score with Owen's oft-quoted line: "All a Poet can do is warn," which would seem to not only express his frustration over the limits of an artist's influence but imply validation of passivity (as in Milton's famous sonnet: "God doth not need / Either man's work or his own gifts; who best / Bear his mild yoke, they serve him best. … / Those also serve who only stand and wait"). Yet the meaning of Owen's line changes when restored to its proper context with the sentence that follows but which Britten omitted: "That is why the true Poets must be truthful." Thus Owen was not suggesting that words alone suffice – indeed, despite his pacifist beliefs, he not only volunteered to fight in the British army but returned to active duty after recovering from his psychic wounds.

Britten prefaced the War Requiem score with Owen's oft-quoted line: "All a Poet can do is warn," which would seem to not only express his frustration over the limits of an artist's influence but imply validation of passivity (as in Milton's famous sonnet: "God doth not need / Either man's work or his own gifts; who best / Bear his mild yoke, they serve him best. … / Those also serve who only stand and wait"). Yet the meaning of Owen's line changes when restored to its proper context with the sentence that follows but which Britten omitted: "That is why the true Poets must be truthful." Thus Owen was not suggesting that words alone suffice – indeed, despite his pacifist beliefs, he not only volunteered to fight in the British army but returned to active duty after recovering from his psychic wounds.  On the contrary, he was emphasizing the responsibility of artists to confront and convey grim reality – and hopefully stimulate progress – rather than lull readers into jingoistic fantasies and complacency.

On the contrary, he was emphasizing the responsibility of artists to confront and convey grim reality – and hopefully stimulate progress – rather than lull readers into jingoistic fantasies and complacency.

A cogent parable told by our rabbi a few years ago: Awakened one night by the din of bells, a traveler learned the next morning that it was an alarm system to arouse neighbors to come and fight a fire. Upon returning home, he recounted this to the elders of his town who were greatly impressed and ordered a bell for each home. When a fire next broke out all the residents duly rang their bells – and kept ringing them as the building burned to the ground. The point, of course, is that warnings are useless unless coupled with appropriate action.