|

A single incident often provides the inspiration for a song. But not for an opera. Peter Grimes is a rare exception.

Benjamin Britten (1913 - 1976)

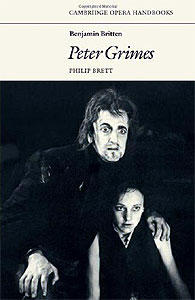

Benjamin Britten and Peter Pears c. 1940 |

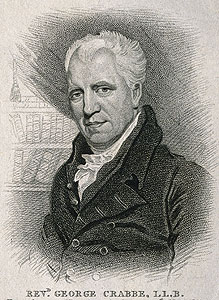

![]() George Crabbe (1754 - 1832) led a comfortable life as an apothecary, parish doctor and Domestic Chaplain to the Duke of Rutland, won some further renown as a cataloguer of beetles, and achieved success as a poet. And yet he had a hard upbringing under his strict father on the melancholy, flat North Sea coast of England, among the poor folk whose lives and surroundings infused his spirit. As aptly summarized by Forster, his poetry has no warm heart, vivid imagination or grand style but rather tartness, acid humor, honesty and a direct feeling for English types and scenery: "He is not one of our great poets. But he is unusual, he is sincere, and he is entirely of this country."

George Crabbe (1754 - 1832) led a comfortable life as an apothecary, parish doctor and Domestic Chaplain to the Duke of Rutland, won some further renown as a cataloguer of beetles, and achieved success as a poet. And yet he had a hard upbringing under his strict father on the melancholy, flat North Sea coast of England, among the poor folk whose lives and surroundings infused his spirit. As aptly summarized by Forster, his poetry has no warm heart, vivid imagination or grand style but rather tartness, acid humor, honesty and a direct feeling for English types and scenery: "He is not one of our great poets. But he is unusual, he is sincere, and he is entirely of this country."

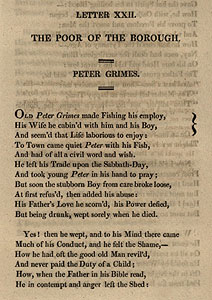

Crabbe's best-known volume is The Borough, published in 1810, which Peter Porter fittingly describes as a demographic survey of the town of Aldeburgh at the beginning of the 19th century. After a fawning dedication, it comprises a 30-page narrative preface and 24 "Letters," each a poem of up to several hundred rhyming couplets, mostly in iambic pentameter, describing an institution (e.g., "Trades," "Amusements," "Inns," "Prisons") or proffering detailed portraits of fictitious yet credible people.

Among those, grouped as "The Poor of the Borough," are Peter Grimes and Ellen Orford, who would become the protagonists in Britten's opera. Yet as described in The Borough neither character seemed inviting for artistic development. A former teacher, Ellen is now an impoverished widow, miserable and blind, cowering from the world's evil and recalling her bitter life of having been seduced, impregnated and abandoned by a faithless lover and then suffering through the deaths of her three sons and an idiot daughter. Grimes seems even less appealing as a suitably complex opera subject. A thoroughly rotten recluse who had killed three apprentices, we meet him in delirium on his death-bed, haunted by demons of his devout father whom he had abused, and recalling a life of fishing and thievery:

Among those, grouped as "The Poor of the Borough," are Peter Grimes and Ellen Orford, who would become the protagonists in Britten's opera. Yet as described in The Borough neither character seemed inviting for artistic development. A former teacher, Ellen is now an impoverished widow, miserable and blind, cowering from the world's evil and recalling her bitter life of having been seduced, impregnated and abandoned by a faithless lover and then suffering through the deaths of her three sons and an idiot daughter. Grimes seems even less appealing as a suitably complex opera subject. A thoroughly rotten recluse who had killed three apprentices, we meet him in delirium on his death-bed, haunted by demons of his devout father whom he had abused, and recalling a life of fishing and thievery:

With greedy eye he look'd on all he saw,Indeed, in his Preface, Crabbe describes Grimes's mind as "depraved and flinty" and limits his personality to one of "obduracy and apparent want of feeling … untouched by pity, unstung by remorse, and uncorrected by shame." As pacifists and homosexuals, Britten and Pears presumably empathized with Grimes as a social outcast, but Philip Brett goes further to consider their interest liberating, a vehicle to purge fears of hostility between their politics and lifestyle vs. the norms of their homeland to which they were returning. In any event, Britten recognized that Crabbe's tale had elements for a viable plot but, as it stood, was "no more than a bloodthirsty melodrama" and he acknowledged that the character had to be significantly enriched to warrant treatment as the focus of an opera.

He knew not Justice, and he laugh'd at Law;

On all he mark'd, he stretch'd his ready Hand;

He fished by Water, and he filch'd by Land:

Oft in the Night has Peter dropt his Oar,

Fled from his Boat and sought for Prey on shore.

![]() Before returning to England in March 1942, Pears and Britten had outlined scenarios that at first closely adhered to Crabbe's tale, while exploiting its lurid sensationalism – as traced by Brett, their initial take would have begun with a dying father cursing Grimes amid appearances by the ghosts of his apprentices and ended with Grimes going mad and throwing himself into the sea. (Indeed Forster later claimed that if he had written the libretto "I should have introduced [the three apprentices' ghosts] in the last scene, rising out of the estuary, on either side of the vengeful greybeard, blood and fire would have been thrown in the tenor's face, hell would have opened.")

Before returning to England in March 1942, Pears and Britten had outlined scenarios that at first closely adhered to Crabbe's tale, while exploiting its lurid sensationalism – as traced by Brett, their initial take would have begun with a dying father cursing Grimes amid appearances by the ghosts of his apprentices and ended with Grimes going mad and throwing himself into the sea. (Indeed Forster later claimed that if he had written the libretto "I should have introduced [the three apprentices' ghosts] in the last scene, rising out of the estuary, on either side of the vengeful greybeard, blood and fire would have been thrown in the tenor's face, hell would have opened.")

Montagu Slater |

The most significant evolution of the libretto was to create compelling main characters. Crabbe's were one-dimensional and unlikely to bond – Ellen was a woeful victim of circumstance and Grimes just an insensitive brute. Ellen became a fount of empathy, while perhaps the best measure of the scale of Slater's renovation lies in the disparate emphases in commentators' descriptions of the character he crafted for Grimes – from rude, unkempt, irritable and thus driving away his only hope of being understood and redeemed (Brett) to a morally-disturbed, tortured idealist (Matthew Boyden), driven by a desperate need for respectability (Joseph Stevenson) but verbally inarticulate and unable to translate his aspirations to real life action (Howard). Pears considered him neither a hero nor a villain but rather a universal type – "very much of an ordinary weak person who, being at odds with the society in which he finds himself, tries to overcome it and, in doing so, offends against the conventional code, is classed by society as a criminal, and destroyed as such." (Significantly, although ultimately cast as a tenor role, Britten initially conceived Grimes as a baritone, the very voice that Brett deems ambivalent, "half-way between the villainous bass and heroic tenor of operatic tradition." Indeed, the duality of the protagonist's personality is implied by his very name – Ellen plaintively croons "Peter" [OK, so I'm a bit partial to that] while "Grimes" suggests calloused grit to provoke disgust and kindle a mob's ire.)  Several observers feel that Slater went even further, bypassing Grimes altogether as the leading character in favor of the sea (Carpenter), the geographic locale (Porter), the community (Eric White) or society as a whole (Percy Young). Brett melds these images by viewing Grimes as internalizing society's judgment and entering a self-destructive cycle that destroys him, in the process appealing to the alienation of everyone in the audience and thus "connecting the private concerns of a couple of left-wing, pacifist lovers [i.e., Britten and Pears] to public concerns to which almost anyone could relate." Ivan Katz concludes: "There are as many views of the opera and the motivations of its characters as there are Freudians, Jungians and quacks, and the expression of one view will anger those who hold with equal heat the contrary position" (and then Katz himself proceeds to draw an extended parallel with the Parsifal legend, of all things).

Several observers feel that Slater went even further, bypassing Grimes altogether as the leading character in favor of the sea (Carpenter), the geographic locale (Porter), the community (Eric White) or society as a whole (Percy Young). Brett melds these images by viewing Grimes as internalizing society's judgment and entering a self-destructive cycle that destroys him, in the process appealing to the alienation of everyone in the audience and thus "connecting the private concerns of a couple of left-wing, pacifist lovers [i.e., Britten and Pears] to public concerns to which almost anyone could relate." Ivan Katz concludes: "There are as many views of the opera and the motivations of its characters as there are Freudians, Jungians and quacks, and the expression of one view will anger those who hold with equal heat the contrary position" (and then Katz himself proceeds to draw an extended parallel with the Parsifal legend, of all things).

A year after the premiere Slater published his own version of the libretto, which Britten had altered to better fit the music he had in mind and stage director Eric Crozier had made more colloquial. Perhaps to deflect any conjecture of creative friction, Slater asserted in a preface that he had worked in "closest consultation" with Britten and that his version merely omitted some of the repetitions and inversions required by musical, as opposed to literary, form. While allowing that he had cast the prologue in verse and had used a variety of meters for the set numbers, Slater asserted that for the body of the drama he had chosen four-stress lines with rough rhymes. He noted that the five-stress lines used by Crabbe had been traditional in English poetic drama but that their rotundity was "out of key with contemporary modes of thought and speech," as opposed to four-stress lines that have a "conversational rhythm" and "sense of naturalness." He further expressed hope that "the return of the rough rhyme [e.g., using assonance (repeated vowels, as in "No more storm") and consonantal rhyme (repeated consonants, as in "Would you stop our storm for such as you")] is likely to help the return of poetic drama to the English stage."

![]() Back home and with the libretto in place, Britten began composing in January 1944. That summer he joked that he was racing the war to see which would finish first and that he hoped the war would win. It didn't – he completed the score on February 10, 1945, three months before V-E Day.

Back home and with the libretto in place, Britten began composing in January 1944. That summer he joked that he was racing the war to see which would finish first and that he hoped the war would win. It didn't – he completed the score on February 10, 1945, three months before V-E Day.

In its final form, Peter Grimes comprises a prologue and three acts, each with two scenes:

- Prologue ~ A Coroner's Court grudgingly concludes that the death of fisherman Peter Grimes's apprentice was accidental, but the townsfolk continue to gossip. Widowed schoolmistress Ellen Orford empathizes with Grimes and implores him to come away with her to start a new life.

The Aldeburgh Moot [City] Hall, c. 1550 (drawn by Thomas Churchyard, 1850) |

- Act I, Scene 1 ~ A few days later on the main village street the residents sing of their hard life. As he brings his boat ashore Grimes is largely shunned. Despite misgivings, arrangements are made to being him a new apprentice from the workhouse. Ellen defends her interest in helping Grimes. A storm threatens. Captain Balstrode, a retired skipper, urges Grimes to leave, but he commits to stay and dreams of redeeming himself by marrying Ellen, but only once he has worked hard enough to become wealthy and respectable.

- Act I, Scene 2 ~ Inside the Boar Inn that night, as the storm rages outside and the residents become rowdy Balstrode leads a sea chantey to defuse a fight. Grimes enters and shares a mystical vision. Ellen brings the new apprentice. In spite of her doubts and the crowd's censure, Grimes rushes out with him into the storm.

- Act II, Scene 1 ~ On the street a few weeks later, outside a Sunday service Ellen discovers bruises on the apprentice and quarrels with Grimes, who is eager to go fishing and leaves for his hut. The men set out to investigate; the women commiserate.

- Act II, Scene 2 ~ In his hut on a cliff edge Grimes brusquely orders the boy to prepare. Recollections of his prior apprentice intrude on a reverie of hope. Hearing the approaching mob, Grimes rushes the boy out the cliff-side door. The boy falls to his death and Grimes follows down the cliff. Finding the hut empty, the posse leaves but Balstrode remains to look around.

- Act III, Scene 1 ~ On the street a few nights later, Ellen is overheard saying that a jersey she had made for the boy has washed up on the shore. Armed and fueled by rumor, the men spread out to hunt down Grimes.

Moot Hall, restored and relocated in 1855 |

- Act III, Scene 2 ~ Later that night, Grimes sneaks back to his boat, swathed in his delusions. Ellen realizes he is beyond help. Balstrode tells him to sail off, scuttle his boat and go down with it. As dawn breaks the town comes to life; shrugging off a rumor of a boat sinking out at sea, its good citizens begin another day.

Omitted from this heavily abridged and admittedly shallow synopsis are supporting characters who enrich the fabric of the community, even as their hypocrisy affords a forceful subtext of social commentary – Swallow, the mayor, is a lecher; Bob Boles, a smug preacher, has a taste for drinking and women; Mrs. Sedley, a self-righteous busybody, is a drug addict; Ned Keene, the town apothecary, is a quack; Auntie, the landlady of the Boar Inn, sidelines as a pimp; and her two "Nieces" flirt with her customers. Although a major presence, the new apprentice is never heard (other than a terse scream as he falls to his death) but bears mute witness to the turmoil in his own mind, a device that effectively requires the other characters to absorb, distill and convey his thoughts and emotions through their own filters. (Notably, the secondary lead in Britten's final opera, Death in Venice, is also a boy in a silent role.) A far more detailed digest of the plot accompanies nearly every LP or CD set of the opera; Patricia Howard's Operas of Benjamin Britten presents a full analysis of the interplay of music, drama and characters.

![]() One of the most striking features of Britten's music is the vocal writing, which still can sound odd compared to the settings of text to which we are accustomed and for which the music supports natural speaking patterns. Ethan Mordden considers the odd intervals in Britten's vocal lines as his unique signature, as contrasted with the English national vocal tradition of pious and patriotic chorales and folk songs. Britten himself explained:

One of the most striking features of Britten's music is the vocal writing, which still can sound odd compared to the settings of text to which we are accustomed and for which the music supports natural speaking patterns. Ethan Mordden considers the odd intervals in Britten's vocal lines as his unique signature, as contrasted with the English national vocal tradition of pious and patriotic chorales and folk songs. Britten himself explained:

In the past hundred years, English writing for the voice has been dominated by strict subservience to logical speech-rhythms, despite the fact that accentuation according to sense often contradicts the accentuation demanded by emotional content. Good recitative should transform the natural intonations and rhythms of everyday speech into memorable musical phrases … if the prosody of the poem and the emotional situation demand them … which may need prolongation far beyond their normal speech length or speed of delivery that would be impossible in conversation.To cite a single example,

consider the first part of this line sung at the end of the inquest by Swallow, the lawyer suspicious of Grimes's treatment of his apprentices. If spoken on stage, the accents likely would be placed: "Pe-ter Grimes' [pause] – I here ad-vise' you" and in a traditional musical setting the longest and highest notes similarly would accompany and thus accentuate the same two syllables. As set by Britten, though, the rhythm is nearly steady, thus suggesting a cold rote warning, and the highest notes highlight "I," so as to emphasize Swallow's ego, and the entire word "advise," as though to stress the situation's gravity. (Hans Keller notes that this same tune, although otherwise seldom heard, opened the opera in a brief preface to the inquest prologue; perhaps the link is meant to subtly underscore the centrality of Grimes's defiance of authority and thus pinpoint the source of his plight.) The second part of the line is far more conventional with an orthodox recitative scale and a suggestion of melodic progression, the stylistic familiarity of that portion serving to underscore the distinctiveness of the setting of the preceding segment. Significantly, its highest pitch and the break from the steady sixteenth note motion, and thus the dramatic emphasis, lies on the word "boy," thus calling particular attention to the vulnerability of a youngster exposed to the rigors of Grimes's trade, while at the same time the decending notes and more deliberate pacing of the phrase "boy apprentice" subtly warn of the newcomer's doom.

consider the first part of this line sung at the end of the inquest by Swallow, the lawyer suspicious of Grimes's treatment of his apprentices. If spoken on stage, the accents likely would be placed: "Pe-ter Grimes' [pause] – I here ad-vise' you" and in a traditional musical setting the longest and highest notes similarly would accompany and thus accentuate the same two syllables. As set by Britten, though, the rhythm is nearly steady, thus suggesting a cold rote warning, and the highest notes highlight "I," so as to emphasize Swallow's ego, and the entire word "advise," as though to stress the situation's gravity. (Hans Keller notes that this same tune, although otherwise seldom heard, opened the opera in a brief preface to the inquest prologue; perhaps the link is meant to subtly underscore the centrality of Grimes's defiance of authority and thus pinpoint the source of his plight.) The second part of the line is far more conventional with an orthodox recitative scale and a suggestion of melodic progression, the stylistic familiarity of that portion serving to underscore the distinctiveness of the setting of the preceding segment. Significantly, its highest pitch and the break from the steady sixteenth note motion, and thus the dramatic emphasis, lies on the word "boy," thus calling particular attention to the vulnerability of a youngster exposed to the rigors of Grimes's trade, while at the same time the decending notes and more deliberate pacing of the phrase "boy apprentice" subtly warn of the newcomer's doom.

As a general matter, Matthew Boyden notes that Britten shunned lushness – he especially despised Puccini – and that his sense of elemental austerity reflects an essentially pessimistic view of humanity. Britten: "The only thing which moves me about singing is that the voice is something that comes out naturally from … personality. I loathe what is normally called a 'beautiful voice.'"  For Howard, though, the trial scene went too far, sacrificing spontaneity for "the turgid diction and ponderous sentence lengths of the choruses" and, indeed, some of the phrasing throughout the libretto does seem unduly strained. (In his opera survey Henry Simon cautioned that Peter Grimes threatened to alienate audiences not only by its "rather repellent subject matter" but by the "almost tortured language of the libretto.") Yet perhaps that was Montagu's and Britten's intention – to impugn the inquest as a callous formality, and all the characters but Grimes and Ellen as too focused on the rigors of daily survival to be able to indulge in the refinement of poetry.

For Howard, though, the trial scene went too far, sacrificing spontaneity for "the turgid diction and ponderous sentence lengths of the choruses" and, indeed, some of the phrasing throughout the libretto does seem unduly strained. (In his opera survey Henry Simon cautioned that Peter Grimes threatened to alienate audiences not only by its "rather repellent subject matter" but by the "almost tortured language of the libretto.") Yet perhaps that was Montagu's and Britten's intention – to impugn the inquest as a callous formality, and all the characters but Grimes and Ellen as too focused on the rigors of daily survival to be able to indulge in the refinement of poetry.

Britten devotes about one-fifth of the total running time to atmospheric Interludes, discussed below, which set the emotional moods that resonate through the scenes that follow. Thus freed from the need to constantly underscore the action with suggestive music, Britten instead uses his orchestra economically to complement the singing with suggestions of the characters' thinking. On the most basic level, Britten clearly signals characterization through associated music: simple scales to depict Ellen's moral rectitude, a sinuous phrase to underline Mrs. Sedley's suspicions, and Peter and Ellen at first singing in keys a half-tone apart as though to suggest distance and even a degree of friction, and then melding together so as to imply the chance of a harmonious future. Taken to the other extreme, several of Grimes's passages are virtually unaccompanied, so as not to distract focus from his aspirations and delusions, and Balstrode's final directive is spoken dispassionately over a silent background, as if to ward off any need for elucidation of harsh reality.

Although through-composed, far more of the opera than might be expected in an innovative, modern work comprises rather traditional arias in which Grimes or Ellen brings the action to a halt so as to confide to us their innermost thoughts. Thus Peter interrupts his frenzied preparations to catch a shoal of fish to serenely dwell on "some kindlier home / Warm in my heart and in a golden calm / Where there'll be no more fear and no more storm;" and between finding the new apprentice's sweater washed up on shore and acting on her discovery Ellen summons a reverie of her childhood "dreams of a silk and satin life." Perhaps the most extraordinary aria is "Now the great Bear and Pleiades" in which in the midst of a storm Grimes ruminates mystically upon the dominance of fate, revealing at once his tender veiled soul and his detachment from the mundane concerns of his neighbors. ("Now the great Bear and Pleiades where earth moves / Are drawing up the clouds of human grief / Breathing solemnity in the deep night.") For Howard, that aria is the key to the entire work, assuring us of the inarticulate Grimes's essential good, its beauty making the opera a tragedy.

Peter Grimes at Sadler's Wells (1945 premiere) and at the Met (1948) |

As unifying devices, White points out the occasional use of repeated motifs to suggest parallels between characters and plot developments; at its most patent level, the music that began Act I reappears to end Act III, thus not only serving as a formal frame but affirming that nothing has changed, no lesson learned nor redemption earned from all that has transpired (and thus flouting the very essence of tragic drama). While an early critic slammed Britten for an absence of melody, that's true only from the traditional perspective of extended baroque, classical and romantic structural development and reflects more a general distaste for modern music than a specific reproach of Britten; indeed, the opera is full of fleeting thematic fragments that constantly tantalize without overstaying their welcome (and the few that do repeat incessantly, as when the crowd's anger rises to frenzy – "Grimes is at his exercise" – are intended to grate). As Alfred Frankenstein noted: "Peter Grimes is not the type of opera wherein all the real musical expression takes place in meditative, lyrical or atmospheric passages. There is action in the score as well as on the stage. Peter Grimes is a musical drama." Ernest Newman agreed: "Britten conceives the drama so entirely in terms of music, and the music so entirely in terms of drama, that there is no drawing a dividing line between the two." For those interested in the utmost detail of Britten's approach, David Matthews devotes 25 pages in the Cambridge Opera Handbook to musical analysis of a single scene.

![]() Each scene except the Prologue is introduced by a substantial orchestral piece. Beyond their practical necessity to enable the stage crew to change the sets within each act, the Interludes serve a far more integral function.

Each scene except the Prologue is introduced by a substantial orchestral piece. Beyond their practical necessity to enable the stage crew to change the sets within each act, the Interludes serve a far more integral function.

Frank Bridge |

It has to do with the people in the village." As though nature itself validated Britten's view, much of the town Crabbe knew, including his home, has since been lost to sea erosion and its iconic Moot Hall had to be moved inland.

It has to do with the people in the village." As though nature itself validated Britten's view, much of the town Crabbe knew, including his home, has since been lost to sea erosion and its iconic Moot Hall had to be moved inland.

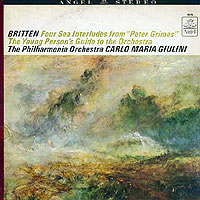

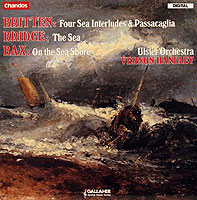

A week before the premiere, Britten conducted in concert four of the interludes (ordered 1-3-5-2 so as to form a logical progression, opening with a languid depiction of dawn and ending with powerful storm music). Eventually he published them as a separate work, along with the fourth passacaglia interlude. The suite, entitled Four Sea Interludes, became one of Britten's most popular works (surpassed on record only by his Simple Symphony and Young Person's Guide to the Orchestra). Of its over two dozen studio recordings (compared to four for the opera itself), one in particular has special emotional resonance – Leonard Bernstein opened his final concert (DG, 1990) with the Four Sea Interludes, thus coming full circle from having led the American premiere of the opera 45 years earlier near the start of his career. (But while it's more energetic than the plodding Beethoven Seventh that closed that final concert, his 1973 recording with the New York Philharmonic (Columbia LP; Sony CD) is far more vibrant, yet offset by an especially relaxed "Moonlight" taken far slower than in Britten's own performance.) Among other recordings I've heard, Britten/Covent Garden (Decca, 1960) preserves the author's prerogative, von Beinum/Concertgebouw (Decca, 1955) gains intensity through consistently faster tempos, although the recording obscures many details, Giulini/Philharmonia (EMI, 1962) broadens the "Moonlight" and "Storm" episodes and boasts wide dynamic range, Previn/London Symphony (Angel, 1976) is full-blooded and forceful, and Hadley/Ulster (Chandos, 1999) tends to clarify the textures and is paired with the Bridge Sea.

By attracting vastly disparate yet convincing interpretive descriptions among commentators, the Interludes attest not only to the breadth of Britten's creative inspiration but more generally to the ability of abstract music to evoke deeply personal associations within each listener.

the Interludes attest not only to the breadth of Britten's creative inspiration but more generally to the ability of abstract music to evoke deeply personal associations within each listener.

- I ~ Dawn ~ Although it comes after the cold start of the inquest prologue, Peggy Cochrane considers this first interlude to serve as the proper prelude to the opera. It begins with a gentle flute melody which Stevenson likens to the descent of a soaring seagull, and then adds rippling sixteenth-note figures in the harp, viola and clarinet that could be the waves lapping the shore (Cochrane), birds wheeling away from the reeds (Ben Hogwood) or perhaps a gentle breeze. Robert Donnington points out a hint of unease in the underlying friction of major and minor thirds, but Carpenter alludes to an ecological analog, as the discords in the bass are absorbed by the purity of the higher instruments which play only white notes.

- III ~ Sunday Morning ~ To open Act II, tolling brass chords speckled with playful woodwind and then string interjections suggest the community awakening and preparing for services – "a fine Sunday morning, with sunlight sparkling on the wavelets and church bells ringing" (Cochrane) – and then focusing more somberly on religious obligations of the sabbath.

- V ~ Moonlight ~ As Act III opens the woodwinds dab flecks of light that glimmer atop the low strings' gentle rhythmic rocking of a tranquil summer night. Several commentators suggest that the music depicts not only natural phenomena but Grimes's internal turmoil. Thus Donnington and Cochrane offer that it transcends an emulation of the sea to suggest jabbing doubts that intrude upon Grimes's disturbed mind. To Haywood the near-perfect blend of romance and regret expresses Grimes's tragic plight.

- II ~ The Storm ~

The uproar of this music intrudes upon Grimes's meditation on elusive peace and leaves no doubt that its literal depiction of a storm battering the shore serves as well as a metaphor for the turbulence that roils him. J. W. Garbutt finds a parallel to the storm in King Lear with multiple levels of natural, pictorial, symbolic and psychological meanings. Carpenter hears in the climactic clash of keys a struggle between Grimes's natural character and the world he cannot join. To Howard, the commanding conclusion of emphatic chords signals "fire and brimstone collapsing in a heap like an overrun sea-wall."

The uproar of this music intrudes upon Grimes's meditation on elusive peace and leaves no doubt that its literal depiction of a storm battering the shore serves as well as a metaphor for the turbulence that roils him. J. W. Garbutt finds a parallel to the storm in King Lear with multiple levels of natural, pictorial, symbolic and psychological meanings. Carpenter hears in the climactic clash of keys a struggle between Grimes's natural character and the world he cannot join. To Howard, the commanding conclusion of emphatic chords signals "fire and brimstone collapsing in a heap like an overrun sea-wall."

- IV ~ Passacaglia ~ Although not part of Britten's suite, the fourth interlude often accompanies it. Ironically, although the most formally rigid, it seems the hardest to construe. To shift focus from the women's lament that closes Act II, scene 1 to Grimes in his hut where scene 2 will unfold, Britten invokes the old device of a passacaglia, in which variations ornament repetitions of a theme in the bass, here derived from the chilling "Grimes is at his exercise" motif with which the chorus hounds him. Through 39 iterations of the basic motif, the music begins as a somber lament, becomes increasingly animated with melodic fragments, then turns thoughtful, then insistent, and culminates by rising to an unruly headache. In a booklet accompanying the premiere, Edward Sackville-West asserted that the persistent bass theme represents Grimes's obdurate disposition and the interwoven wandering motif depicts the inability of his apprentice to deal with his sudden changes of moods. Lilienstein instead offers that the immovable bass could represent the tenacity of the Borough, in which case the variations might depict the residents' conflicting thoughts, or perhaps Grimes trying various ways to approach it. While such portrayals of Grimes's psychology are unspecific, they certainly imply that his thoughts are complex while he obsessively contemplates his situation and outlook. David Felsenfeld notes that the first snatch of melody, which returns at the end, is played by a lone viola, Britten's favorite instrument, thus suggesting the composer's identification with his tortured protagonist. At any rate, the passacaglia attests to Britten's creation of a complex musical character that transcends the unavoidable specificity of the libretto.

- VI ~ The last interlude, the only one not excerpted for concert performance, bears no title but provides a brief whispered respite over the steady drone of a fog-horn. Reminiscent of the passacaglia, it seems to evoke both the mist of the sea and the haze in Grimes's mind as the posse nears, his options shrink and his problem must finally be resolved.

![]() Even though Peter Grimes was Britten's first true opera, it arose as he approached the mid-point of his life and reflected many influences and experiences.

Even though Peter Grimes was Britten's first true opera, it arose as he approached the mid-point of his life and reflected many influences and experiences.

After completing his formal education, Britten expanded the scope of his practical knowledge by working at the General Post Office Film Unit, where he produced background soundtrack music for a wide variety of moods, using diverse ensembles. As the subjects of the movies were aspects of British life, Young suggests that this fostered an appreciation that musicians belong to society and that their music should reflect social concerns. Lilienstein further points to Britten's background in scoring radio dramas in which he had to supply vivid musical prompts for what could not be seen. On his own, Britten became best known for several song cycles that attained a reputation for the sensitivity with which he set the English language to music.

After completing his formal education, Britten expanded the scope of his practical knowledge by working at the General Post Office Film Unit, where he produced background soundtrack music for a wide variety of moods, using diverse ensembles. As the subjects of the movies were aspects of British life, Young suggests that this fostered an appreciation that musicians belong to society and that their music should reflect social concerns. Lilienstein further points to Britten's background in scoring radio dramas in which he had to supply vivid musical prompts for what could not be seen. On his own, Britten became best known for several song cycles that attained a reputation for the sensitivity with which he set the English language to music.

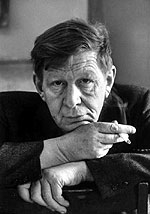

Beyond his personal development, Britten was influenced by numerous outside models, all of which inform the libretto and score for Peter Grimes. He expressed great admiration for Stravinsky's economy, clarity and mastery of orchestral coloring and Mahler's orchestral technique and compositional irony. Among operatic paradigms, two seem especially pertinent. Britten saw a 1942 production of George Gershwin's 1935 Porgy and Bess, which revolved around the social networks in a fishing community repressed by authority and used a storm as a powerful musical device with dramatic overtones. At one point he had wanted to study with Alban Berg, whose 1921 Wozzeck, although more tightly structured, featured a cruelly-abused social outcast failing in love, driven to murder and ultimately drowning himself, a musical interlude summing up his psyche and a devastating final scene depicting the indifference of society to his personal tragedy.

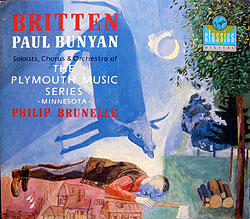

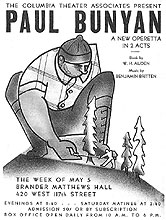

![]() The most important groundwork for Peter Grimes was Paul Bunyan, a 1941 "choral operetta" based on the legendary American pioneer folk hero and intended for Broadway but stalled by harsh press criticism after a brief initial trial run at Columbia University.

The most important groundwork for Peter Grimes was Paul Bunyan, a 1941 "choral operetta" based on the legendary American pioneer folk hero and intended for Broadway but stalled by harsh press criticism after a brief initial trial run at Columbia University.

W. H. Auden |

From a Pressure Group that says I am the Constitution,And Bunyan's final admonition as he takes leave of his flock, nominally summing up the pioneer era, still rings as true as ever:

From those who say Patriotism and mean Persecution,

From a Tolerance that is really inertia and disillusion …

Every day America's destroyed and re-created.Francesca Zambello hails its overall thematic reflection of the American spirit –

America is what you do,

America is I and you,

America is what you choose to make it.

that the establishment of democracy requires that individual and personal freedom be subsumed into the interests of a community – as a plea for tolerance and acceptance of difference sorely lacking in a Europe on the brink of war. Consistent with the breadth of the narrative, the music is consistently captivating and cements Britten's mastery of a wide variety of not only American but universal idioms. Thus Seymour salutes the score as displaying Britten's prowess with an appealing medley of deft pastiches and parody ranging from a Donizetti-style duet to a blues lament. A 1988 Virgin CD set by the Plymouth Music Series Minnesota led by Philip Brunelle captures its essence quite well.

that the establishment of democracy requires that individual and personal freedom be subsumed into the interests of a community – as a plea for tolerance and acceptance of difference sorely lacking in a Europe on the brink of war. Consistent with the breadth of the narrative, the music is consistently captivating and cements Britten's mastery of a wide variety of not only American but universal idioms. Thus Seymour salutes the score as displaying Britten's prowess with an appealing medley of deft pastiches and parody ranging from a Donizetti-style duet to a blues lament. A 1988 Virgin CD set by the Plymouth Music Series Minnesota led by Philip Brunelle captures its essence quite well.

Britten considered revisions but lost interest after returning to England and worked up a final draft only at the very end of his life.  Even so, Porter notes that the failure of Paul Bunyon was therapeutic in that it led Britten to escape the domination of librettists so that henceforth all his operas would be tailored entirely upon his ideas, inspiration and minutely worked-out requirements; as Britten put it: "I felt that I have learned lots about what not to write for the theatre." Even so, Paul Reed hails the score as richly lyrical: "Its easy-going melodies appear as refreshing and seemingly spontaneous as anything written in his long career." Production demands were modest, with the title character only speaking off-stage (just as well, given his legendary size) and relying upon a raconteur singing country-and-western ballads to fill in the narrative gaps that would have required considerable time and costly resources to depict. While Reed sees the eclectic mix of musical styles as a reflection of America's diversity of cultural backgrounds and Zambello views it as a personal voyage of cultural and musical discovery in search for the American idiom, Seymour more cynically suggests that Paul Bunyan was Britten's naïve attempt to assert his artistic credentials for a possible application for American citizenship.

Even so, Porter notes that the failure of Paul Bunyon was therapeutic in that it led Britten to escape the domination of librettists so that henceforth all his operas would be tailored entirely upon his ideas, inspiration and minutely worked-out requirements; as Britten put it: "I felt that I have learned lots about what not to write for the theatre." Even so, Paul Reed hails the score as richly lyrical: "Its easy-going melodies appear as refreshing and seemingly spontaneous as anything written in his long career." Production demands were modest, with the title character only speaking off-stage (just as well, given his legendary size) and relying upon a raconteur singing country-and-western ballads to fill in the narrative gaps that would have required considerable time and costly resources to depict. While Reed sees the eclectic mix of musical styles as a reflection of America's diversity of cultural backgrounds and Zambello views it as a personal voyage of cultural and musical discovery in search for the American idiom, Seymour more cynically suggests that Paul Bunyan was Britten's naïve attempt to assert his artistic credentials for a possible application for American citizenship.

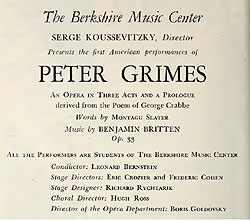

![]() After a performance of his Sinfonia da Requiem by the Boston Symphony, Britten met its Music Director Serge Koussevitzky and discussed his plans for an opera. Koussevitzky commissioned the project, to be dedicated to his late wife, and provided a much-needed monetary advance, with the understanding that he would give the world premiere at his Berkshire Music Festival, with British performances to follow. But when the Festival was postponed Koussevitzky generously ceded the premiere to Britain, where it was given on June 7, 1945.

After a performance of his Sinfonia da Requiem by the Boston Symphony, Britten met its Music Director Serge Koussevitzky and discussed his plans for an opera. Koussevitzky commissioned the project, to be dedicated to his late wife, and provided a much-needed monetary advance, with the understanding that he would give the world premiere at his Berkshire Music Festival, with British performances to follow. But when the Festival was postponed Koussevitzky generously ceded the premiere to Britain, where it was given on June 7, 1945.

Sadler's Wells was a major theatre in London with a history dating from 1683 but it had closed during the War, sent its company on tour, and sought a notable work to mark its grand reopening.

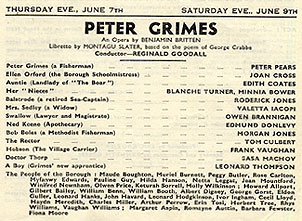

Programs of the Sadler's Wells and American premieres |

Cross persisted and her gamble paid off spectacularly, even prompting a wave of chauvanism. Proclaiming that "a new master has really arrived," Edmund Wilson called Britten "an unmistakable new talent" and his encounter with the opera "an astonishing, and even electrifying, experience" and praised the score as cast in a quintessentially English idiom, free of foreign influences and thus "very different from anything we have been used to." Shawe-Taylor similarly praised the naturalness of the music and the singers' "unusual happiness of singing a text that did not sound like a translation." Crozier felt that the main character "personified the ambitions and frustrations that are latent in all of us" and that the friction between Grimes and the townsfolk epitomized the conflicts that audiences had endured during the War and thus served as a cathartic release. Yet not all reviews were ecstatic. While the Guardian praised the score as "full of vivid suggestion and action, sometimes rising to a level of white-hot poetry," it found the libretto "overloaded with scrappy and not always telling incident, and too much of it is cast in an unreal language," a seemingly curious critique of a work in such a heavily stylized art form. A local review by Scott Goddard proclaimed it "an astonishing work," praised the singing and acting as "intensely moving" but found the music "fascinating as much when it fails" (which he declined to elaborate). Following the August 1946 American premiere, led by a budding Leonard Bernstein, Koussevitzky proclaimed it the greatest opera since Carmen, even though Britten scorned the presentation as an unprofessional student production (as indeed it unabashedly was, with all roles taken by students at the Berkshire Music Center).

Perhaps its most surprising popularity was in East Germany where, Brett notes, it was presented as "a harrowing but authentic picture of the degeneracy of life in Britain."

Perhaps its most surprising popularity was in East Germany where, Brett notes, it was presented as "a harrowing but authentic picture of the degeneracy of life in Britain."

In retrospect Peter Grimes has been widely hailed as nothing less than having launched the revival of English opera after 2½ centuries of languor following the death of Henry Purcell in 1695. (Although broadly couched, all such comments clearly can refer only to serious opera, as they deliberately (and perhaps snobbishly) ignore the dazzling brilliance – and unflagging popularity – of both lyrics and music of the Gilbert and Sullivan canon.) Lamenting the world-wide demise of the genre since Turandot 20 years before, Shaw-Taylor proclaimed Peter Grimes an "all-conquering" work and "a fresh hope, not only for English, but for European opera." Shortly after the premiere, Britten had expressed a wish that the occasion would transcend Sadler's Wells or even himself as an omen for the future of English opera and hoped that others would take the plunge. Matthew Boyden credited it for encouraging Covent Garden and other institutions to embrace new repertoire and for spurring Michael Tippett, William Walton and other British composers to write operas. Britten himself certainly was inspired, as he went on to become the foremost opera composer of the 20th century, spreading the rest of his career across an eclectic variety of subjects drawn from antiquity (The Rape of Lucretia) and the Bible (Noye's Fludde) to Shakespeare (A Midsummer's Night Dream) and more recent literature (Melville's Billy Budd), and designed to be mounted by forces ranging from traditional opera companies to broadcasters, chamber groups and even churches. Stemming from Peter Grimes, nearly all have a common thematic thread of individuals isolated from and chafing against the oppression of society and its hypocritical institutions. Even so, Britten mostly repressed his personal concerns with pacifism and homosexuality (the latter simmering in Billy Budd and then fully emerging in his last opera, Death in Venice).

![]() Peter Grimes has been favored with only four complete studio recordings. This may seem rather scant in light of its reputation and popularity, yet perhaps is to be expected when considering the overwhelming predilection of opera audiences for the core repertoire spanning the era from Mozart through Puccini.

Peter Grimes has been favored with only four complete studio recordings. This may seem rather scant in light of its reputation and popularity, yet perhaps is to be expected when considering the overwhelming predilection of opera audiences for the core repertoire spanning the era from Mozart through Puccini.

Peter Pears, Joan Cross, BBC Theatre Chorus, Royal Opera House Orchestra, Covent Garden, conducted by Reginald Goodall (1948) ~ While the 1958 Decca set (immediately below) was hailed as the first recording of Peter Grimes (and indeed it so seemed at the time), in fact it had been preceded by this one a decade earlier.

Joan Cross |

The 1948 sides are the closest we can ever get to documenting the excitement and initial acclaim of the premiere. Within the 39 minutes are two intact segments – the complete Peter/Ellen/church choir interplay of Act II, Scene 2, prefaced by the third Interlude (albeit played with rather wobbly rhythm), and the rarely-heard sixth Interlude followed by Peter's delusions before he finally sails off to eternity (Act III, Scene 2).

Peter Pears |

While Cross was instrumental in mounting the original production and thus paving the way to its huge success, Pears had an even more special role. Not only did he help develop the scenario and devise the role of Grimes, but he was Britten's artistic collaborator, intimate soul-mate and foremost interpreter.

Reginald Goodall [sic] |

In marked contrast to his synergistic alliances with Cross and Pears, it seems curious that Britten was able to stomach the third member of the original team. While he was an early advocate of Britten's work and a fellow pacifist, conductor Reginald Goodall hardly lived up to his surname. Ultimately leading to fame as a Wagnerian renowned for luminous textures and patient tempos, Goodall's devotion to German music took a vile turn – an ardent fascist, he sympathized so deeply with the Nazis that he not only denied the Holocaust but persisted in asserting that it was a Jewish plot, going so far as to claim that the horrific films of death camp liberation had been faked in BBC studios.

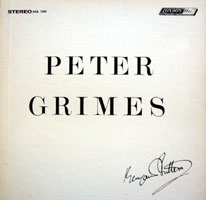

Peter Pears, Claire Watson, Chorus and Orchestra of the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, conducted by Benjamin Britten (Decca/London, 1958) ~ An artistic and commercial triumph, this still remains the model against which every subsequent recording of Peter Grimes is compared and often found wanting.

In the 13 years since the premiere, Pears had become indelibly identified with the character of Grimes, which he presents here with unique authority and even more nuance and maturity.

The stereo soundstage chessboard |

With the vast publicity surrounding release of the first installment of the Solti-led Decca Ring, producer John Culshaw drew audiophiles' attention to the facility of stereo technology to create in the studio a convincing spatial image of an actual staged opera performance (at least from an idealized center-orchestra seat). Yet its innovations were paralleled, if not preceded, here.

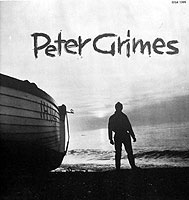

Premiere album and booklet covers |

While reissues and further recordings presented typical appealing cover photos, the original album was notably austere, bearing only the title in block letters and the composer's autograph against a plain white background, as if to avoid suggesting a specific meaning or distracting from the gravity of the subject. (The accompanying booklet, though, did boast a suggestively artless type-face on a stark moody photo of Grimes standing beside his boat and looking out to sea that was also used for a single LP of excerpts.)

Peter Pears, Heather Harper, Chorus and Orchestra of the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, staged by Joan Cross, conducted by Benjamin Britten and directed by Brian Large (BBC Television, 1969) ~ Through a BBC television production Britten sought to preserve "a really authoritative record of how we like it to go and what it is all about." He proposed shooting on location with singing mimed to a prerecorded soundtrack but wound up using studio resources.

On the beach at Aldeburgh, 2013 (Euroarts DVD) |

The result is a brilliant realization on every level. Above all else, it reminds us that opera comprises far more than words and music and their mere inference of a physical presence. Thus even the least of the minor characters emerge as strikingly individual members of the community, the chorus is no mere mass of generic voices but dozens of distinctive personalities each going about his or her business (abetted by the intensity of the entire cast's superb acting), and the boy apprentice, while still unheard, is no longer a disembodied spirit but in pantomime becomes a vivid character, plunged into an alien world where he dotes on Ellen and cringes before Grimes. Yet this is no mere document of a competent staging. Rather, judicious camerawork creates further levels of meaning that enhance the audio clues without calling undue attention to itself. Thus during the passacaglia Grimes and the boy tentatively interact within dense fog as they approach his hut, all the other interludes are bathed in a metaphoric haze with abstract glimmers of light, closeups force our attention to stay fixed on the self-imposed isolation of Grimes and Ellen from the surrounding world and on the depth of their aspirations and suffering, and the mob scene is truly terrifying as the community relentlessly advances and then freezes in unflinching anger.

from the BBC television production – Grimes and Ellen; the mob; Grimes and his apprentice |

Pears was already 35 when he created the role, and a quarter-century later his Grimes takes on added poignancy, as he clearly looks way too old to achieve his dream and thus seems doomed to fail. Harper, too, bears her burden with dignity despite realizing that the challenge of taming Grimes remains her only hope of finding contentment even as it, too, becomes increasingly beyond reach.

In a probing analysis, Rosemary Harvey traces how camera angles and closeups intensify the dramatic and emotional impact by creating physical and psychological vantage points that are not possible from the fixed audience view in stage productions. She further contrasts Pears's use of large gestures to define his public personality in conflict with the crowd against small introverted movements, shot more closely, to define a more personal intimacy and to facilitate a sympathetic connection with Ellen and the camera (and, by proxy, us as viewers). In particular Harvey details the characterization that emerges as Grimes and his apprentice walk toward his hut during the fourth Interlude, an invention with no counterpart in the staged opera. (Presumably stage director Cross and/or film director Large, rather than Britten or Pears, were responsible for these striking visuals.)

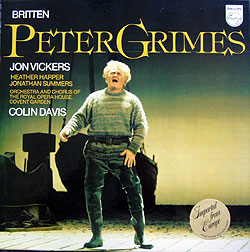

Jon Vickers, Heather Harper, Orchestra and Chorus of the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, conducted by Colin Davis (Philips, 1978)

The first serious challenge to the monopoly of the Pears/Britten Grimes arose in 1967 with a new Met production starring Jon Vickers and led by Colin Davis.

Britten's vision for his protagonist (exemplified, of course, by Pears) was: "not too heavy, which makes the character simply a sadist, nor too lyric, which makes it a boring opera about a poet-manqué … but [he] should have elements of both." While Pears and Britten melded the poles of Grimes's persona into a credible if piteous whole, Vickers and Davis displayed his extremes in all their challenging clout and discord. To Tom Rosenthal, Vickers "evoked the elements of tragedy, pity, terror and catharsis with raw, unforgettable emotional power." Brett aptly describes the result as powerful, tragic, intense, dramatic and monumental. Davis put it more graciously: "We had a feeling [that Britten] hadn't quite realized what he set loose. It's a very violent piece. … I think he thought I took too much freedom with it." Vickers was more blunt, contending in an interview that Britten and Pears both "held it so close to their eyes that they blotted out the universe."

"not too heavy, which makes the character simply a sadist, nor too lyric, which makes it a boring opera about a poet-manqué … but [he] should have elements of both." While Pears and Britten melded the poles of Grimes's persona into a credible if piteous whole, Vickers and Davis displayed his extremes in all their challenging clout and discord. To Tom Rosenthal, Vickers "evoked the elements of tragedy, pity, terror and catharsis with raw, unforgettable emotional power." Brett aptly describes the result as powerful, tragic, intense, dramatic and monumental. Davis put it more graciously: "We had a feeling [that Britten] hadn't quite realized what he set loose. It's a very violent piece. … I think he thought I took too much freedom with it." Vickers was more blunt, contending in an interview that Britten and Pears both "held it so close to their eyes that they blotted out the universe."

According to Rosenthal, Britten was furious with Vickers for "riding roughshod over the score, changing words, eliding syllables here and there, creating different emphases." (And yet, at least as reflected in the LP booklet, the departures from the libretto are few and quite minor, mostly involving single words.) The different interpretation of the title character is evident from the very outset, as Grimes takes the oath at his inquest – Pears is barely audible,

Balstrode sends Grimes away (from the 1981 video) |

The same principals (Vickers, Harper, Covent Garden, Davis) issued a 1981 video (Kultur DVD) but it's disappointing compared to the BBC production. It certainly succeeds in adding a visual element to Vickers's riveting portrayal of the title role, documenting his expansive acting and vivid gestures to complement the intensity of his vocal portrayal. Yet in most other respects it's a dull, uninspired record of a stage-bound rendition with bare sets, minimal props, dim lighting, gloomy costumes and a largely static chorus that generates little more interest than watching an oratorio. Indeed the most dynamic images tend to be of the orchestra performing the interludes. Frankly, it seems more involving to imagine the opera's full scope by listening to the audio-only LP or CD. Even so, it avoids the danger of the BBC conception, whose characters and visuals are so compelling as to threaten to overwhelm the impact of most other productions and to hijack our imaginations with its specific imagery.

Perhaps the key takeaway here is that no masterpiece can properly be limited to a single interpretation, not even that of its creators, and that often it takes others to mine further, and potentially richer, veins. Vickers and Davis not only crafted their own valid and different revelation but opened the door for others to venture beyond the initial edifice.

Anthony Rolfe Johnson, Felicity Lott, Chorus and Orchestra of the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, conducted by Bernard Haitink (EMI, 1993)

Another 15 years brought this third complete studio recording with the same orchestra as the prior two studio sets.  Here, too, the opening inquest scene establishes the fundamental perspective and central conflict while asserting its individuality, as the crowd, barely heard in the Britten and Davis recordings beyond its prescribed choral interjections, breaks out in raucous derision as Grimes struggles to state his case. A pupil of Pears, Rolfe Johnson inherited his mentor's mantle of sweet, intelligent sensitivity, although his voice is far more mellow, creating a less assertive and more suave characterization, nicely paired here with Lott's rich, dreamy lyricism. Stemming from his considerable experience in the German/Austrian orchestral repertoire, Haitink crafts a rich, symphonic texture which the recording fully conveys (but which some critics have belittled as ponderous). Speaking of critics, two reviews in Fanfare serve to illustrate the extremely subjective nature of esthetic judgments (and reinforce my hesitancy to enter that fray): Ivan Katz called out Johnson's singing as "passionless," "characterless, without distinction or personality" and "devoid of feeling," whereas Marc Mandel in a later issue of the same publication found him to be "sympathetic," "movingly human" with "painstaking (and painful) delineation of Grimes's moment-to-moment mood swings" and "frighteningly unique." Although both agree that the production lacks forward motion and cumulative impact, overall the EMI set strikes me as a reasonable Grimes, even if it declines to match the more distinctive portrayals of its predecessors.

Here, too, the opening inquest scene establishes the fundamental perspective and central conflict while asserting its individuality, as the crowd, barely heard in the Britten and Davis recordings beyond its prescribed choral interjections, breaks out in raucous derision as Grimes struggles to state his case. A pupil of Pears, Rolfe Johnson inherited his mentor's mantle of sweet, intelligent sensitivity, although his voice is far more mellow, creating a less assertive and more suave characterization, nicely paired here with Lott's rich, dreamy lyricism. Stemming from his considerable experience in the German/Austrian orchestral repertoire, Haitink crafts a rich, symphonic texture which the recording fully conveys (but which some critics have belittled as ponderous). Speaking of critics, two reviews in Fanfare serve to illustrate the extremely subjective nature of esthetic judgments (and reinforce my hesitancy to enter that fray): Ivan Katz called out Johnson's singing as "passionless," "characterless, without distinction or personality" and "devoid of feeling," whereas Marc Mandel in a later issue of the same publication found him to be "sympathetic," "movingly human" with "painstaking (and painful) delineation of Grimes's moment-to-moment mood swings" and "frighteningly unique." Although both agree that the production lacks forward motion and cumulative impact, overall the EMI set strikes me as a reasonable Grimes, even if it declines to match the more distinctive portrayals of its predecessors.

A curious note: the booklet to the original CD issue lists every vocalist having even a single solo line (e.g., 2nd Fisherman, 6th Burgess) and even the apprentice (whose sole audible contribution is an attenuated death-plunging yelp) but omits mention of any instrumentalist other than the player of Hobson's drum, although admittedly that does accurately reflect the weighting we assign to the predominance of singing to the exclusion of most other artists who contribute to the impression of an opera. And speaking of documentation, a subsequent CD reissue pushes the libretto and liner notes onto a third bonus disc, but I question whether staying glued to a computer screen enhances the experience of consulting a printed booklet in an accustomed home listening environment.

Philip Langridge, Janice Watson, Opera London, London Symphony Chorus, City of London Sinfonia, conducted by Richard Hickox (Chandos, 1996)

This last studio Grimes was also the first to break away from Covent Garden. Hickox had founded the London Sinfonia in 1971 and led it for the next 37 years until he suffered a fatal heart attack during a recording session.  Cemented by their quarter-century association at the time of this release, the bond here between conductor and players is expectedly tight. The credits make no mention of augmentation of the Sinfonia's standard 40 or so musicians, but it sounds far more like a full orchestra than a pit band, both lending a sense of intimacy to the proceedings where appropriate and conjuring riveting power in the storm interlude and other potent episodes, enriched by a deep and atmospheric recording. Langridge captures Grimes's shifting moods with vivid sensitivity, and while Watson may lack the mature nurturing sound of the other studio Ellens she brings an uncommon innocence to her role, adding a special layer of poignancy to the principals' fraught relationship. The credits extend even further into the realm of the absurd, listing the portrayer of the Apprentice – a silent role in an audio recording! – as the second lead right below Grimes and ahead of Ellen, Balstrode and all the others who actually sing.

Cemented by their quarter-century association at the time of this release, the bond here between conductor and players is expectedly tight. The credits make no mention of augmentation of the Sinfonia's standard 40 or so musicians, but it sounds far more like a full orchestra than a pit band, both lending a sense of intimacy to the proceedings where appropriate and conjuring riveting power in the storm interlude and other potent episodes, enriched by a deep and atmospheric recording. Langridge captures Grimes's shifting moods with vivid sensitivity, and while Watson may lack the mature nurturing sound of the other studio Ellens she brings an uncommon innocence to her role, adding a special layer of poignancy to the principals' fraught relationship. The credits extend even further into the realm of the absurd, listing the portrayer of the Apprentice – a silent role in an audio recording! – as the second lead right below Grimes and ahead of Ellen, Balstrode and all the others who actually sing.

![]() As of this writing (2019) nearly a further quarter-century has elapsed since release of the Chandos set. The prospect of another studio Grimes seems increasingly unlikely, given the declining economics of the recording industry and the formidable expense of mounting a new world-class production solely for the microphones. Indeed, from a purely technical perspective little has changed since the first complete Peter Grimes on record and its then-innovative use of stereo, as the multi-channel revolution largely managed to bypass opera and the sonic improvements of digital technology seem marginal (and, to the discerning ears of some audio buffs, illusory or worse when compared to good analog work). The upshot seems unfair to today's artists, who must face the daunting prospect of having to compete with the giants of the past, whose talent in prior times would have quickly faded into mere wistful, anecdotal memories but now are forever enshrined in credible sound.

As of this writing (2019) nearly a further quarter-century has elapsed since release of the Chandos set. The prospect of another studio Grimes seems increasingly unlikely, given the declining economics of the recording industry and the formidable expense of mounting a new world-class production solely for the microphones. Indeed, from a purely technical perspective little has changed since the first complete Peter Grimes on record and its then-innovative use of stereo, as the multi-channel revolution largely managed to bypass opera and the sonic improvements of digital technology seem marginal (and, to the discerning ears of some audio buffs, illusory or worse when compared to good analog work). The upshot seems unfair to today's artists, who must face the daunting prospect of having to compete with the giants of the past, whose talent in prior times would have quickly faded into mere wistful, anecdotal memories but now are forever enshrined in credible sound.

Yet, perhaps the dusk of the era of studio audio opera recordings should not be a cause for distress. Opera, after all, is as much a visual experience as an aural medium. While listening to an audio-only opera recording can (and, ideally, should) unleash one's personal imagination, even the best can preserve only part of the intended impact, and so perhaps the future of recorded opera properly lies in videos of live renditions. (Indeed, the operadis site lists 19 of Peter Grimes so far.) That, in turn, raises a challenge for the director, as reflected in comparing the Pears/Britten and Vickers/Davis videos. Faithful documentation of a staged performance can seem a bland substitute for the actual experience, but application of creative input to shape meaning risks distorting the original conception through over-interpretation and, through aggressive editing and close-ups, forces us to dwell on isolated fragments of an overall presentation while neglecting other salient details and the overall atmosphere. Yet even if video (much less audio-only) recordings can provide but a pale trace of the full theatrical experience, at least they can enable new artists to preserve their talent along with the legions of past stars and to reach global audiences, while serving to expose millions, to whom live opera is inaccessible or unaffordable, to a genre that is justifiably regarded as a pinnacle of our culture.

|

![]() I gratefully acknowledge the following sources for the facts, quotations and attributions in this article, while accepting credit (and, alas, blame) for the other observations, assertions and opinions:

I gratefully acknowledge the following sources for the facts, quotations and attributions in this article, while accepting credit (and, alas, blame) for the other observations, assertions and opinions:

- Abbate, Carolyn and Roger Parker: A History of Opera (Norton, 2012)

- "Benjamin Britten at Sadler's Wells" (Sadler's Wells Theatre Archive, 19 November 2013)

- Blyth, Alan: review of the EMI reissue of the 1948 Peter Grimes excerpts (Gramophone, February, 1994)

- Boyden, Matthew: The Rough Guide to Opera (Rough Guides, 2007)

- Brett, Philip: Cambridge Opera Handbook: Benjamin Britten: Peter Grimes (Cambridge University, 1983)

- Brett, Philip: "Benjamin Britten," article in Stanley Sadie, ed., The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians (MacMillan, 2001)

- Carpenter, Humphrey: Benjamin Britten – A Biography (Scribner's, 1992)

- Cochrane, Peggy: "Synopsis" in the Britten Peter Grimes LP (London OSA 1305, 1958)

- Crabbe, George: The Borough (J. Hatchard, 1810)

- Crozier, Eric: "Pity and Pain – the First Production of 'Grimes'," notes to the reissue of the 1948 Peter Grimes excerpts (EMI Classics 7 64727 2, 1993)

- Donington, Robert: Opera and Its Symbols (Yale, 1990)

- Felsenfeld, David: Britten and Barber – Their Lives and Their Music (Amadeus, 2005)

- Forster, E. M.: "George Crabbe: The Poet and the Man" (The Listener, May 29, 1941)

- Frankenstein, Alfred: review of the Britten recording (High Fidelity, March 1960)

- Garbutt, J. W.: "Music and Motive in Peter Grimes" (Music & Letters, XLIV, 1963)

- Harvey, Rosemary Alyce: "Gesture and Sympathy in the 1969 BBC Production of Benjamin Britten's 'Peter Grimes'" (MA Thesis) (University of British Columbia, 2014)

- Heywood, Ben: "Listening to Britten: Peter Grimes" (Good Morning Britten, October 6, 2013)

- Howard, Patricia: The Operas of Benjamin Britten (Praeger, 1969)

- Katz, Ivan: review of the Haitink EMI CDs (Fanfare, January/February, 1994)

- Keller, Hans: "The Story, the Music Not Excluded," in Philip Brett, ed.: Cambridge Opera Handbook: Benjamin Britten: Peter Grimes (Cambridge University, 1983)

- Lilienstein, Saul: Peter Grimes (Washington National Opera Commentaries on CD, 2009)

- Lucas, John: "Goodall and Britten, Grimes and Lucretia," notes to the reissue of the 1948 Peter Grimes excerpts (EMI Classics 7 64727 2, 1993)

- Mandel, Marc: review of the Haitink recording (Fanfare, September/October 1966)

- Matthews, Colin: notes to the Haitink Peter Grimes CD (EMI 7 54832 2, 1993)

- Mordden, Ethan: The Splendid Art of Opera (Methune, 1980)

- Pears, Peter: "Neither a Hero Nor a Villain," (Radio Times, March 8, 1946)

- Porter, Peter: "Benjamin Britten's Librettos" in Nicholas John, ed.: English National Opera Guide (Riverrun, 1983)

- Powell, Neil: Benjamin Britten – A Life For Music (Henry Holt, 2013)

- Reed, Paul: "Britten's American Dream," notes to the Hickox Peter Grimes CD (Chandos CHAN 9781(2), 2007)

- Reed, Philip: "Fiery Visions," notes to the Paul Bunyan CD (Chandos CHAN 9447/8, 1996)

- Rosenthal, Tom: "Who Was the Real Peter Grimes?" (Independent, June 27, 2004)

- Seymour, Claire: "Benjamin Britten: Peter Grimes" (Opera Today, February 22, 2014)

- Simon, Henry: 100 Great Operas and their Stories (Doubleday, 1960)

- Slater, Montagu: Peter Grimes and Other Poems (The Bodley Head, 1946)

- Smith, Eric: "The Recording," notes to the Britten Peter Grimes LP (London OSA 1305, 1958)

- Stevenson, Joseph: "Britten Roundup" (Classical Compact Disc Guide, Vol. 8 # 1 (February-March 1993)

- White, Eric Walter: "Britten's Peter Grimes," notes to the Davis Peter Grimes LP (Philips 6769 014, 1978)

- Young, Percy: Britten (David White, 1996)

- Zambello, Francesca: "Notes From the Director," notes to the Paul Bunyan CD (Chandos CHAN 9781(2), 2007)

Copyright 2019 by Peter Gutmann

copyright © 1998–2019 by Peter Gutmann. All rights reserved.