|

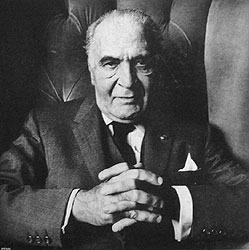

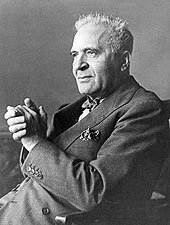

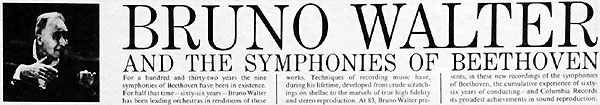

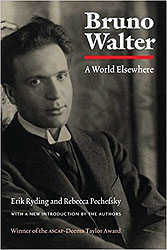

All conductors evolve throughout their careers – some subtly (Reiner, Monteux, Ansermet), others more palpably yet steadily (Bernstein, Toscanini, Celibidache). Among all the giants of the baton, Bruno Walter (1876 – 1962) was unique, as his interpretive outlook changed more suddenly, more often and more radically than any other.

Far too often Walter's final series of stereo recordings dominates commentaries and eclipses all that preceded them. Thus in Harold Schonberg's The Great Conductors we read: "As an interpreter he represented dignity, nobility, compassion. … [H]is rhythms were smooth-flowing, inevitable-sounding, undistorted by rubato. … He made music lovingly. … There never was a strained moment, never a trace of hysteria" but rather a "relaxed, comforting, … genial, unhurried, fluid approach." Such descriptions are apt, but pertain only to the very close of a long musical life of sweeping change and diverse disposition.

→To avoid confusion or worse, let me be clear at the outset about what this article is – and is not. It does not purport to be a biography, a comprehensive discography or a probing analysis of Walter's recordings or of the underlying works. In the references section below I've suggested other sources for the first two and I'm both disinclined and ill-equipped for the rest. Rather, it's my attempt to trace the evolution of his interpretive art throughout an extraordinary career, with especial emphasis on the phases most commentators gloss over or altogether ignore.

Walter's early career followed the typical arc for conductors raised in late 19th-century European traditions, but with one grand distinction. Nurtured as a child prodigy, he first seemed destined for a calling as a concert pianist, dabbled in composition, was galvanized by a single experience (here, attending an 1888 concert conducted by Hans von Bulow), was enthralled by the revelation of Wagner, rose through the ranks of vocal coach and assistant conductor in increasingly prestigious opera houses, and ultimately was entrusted with orchestral assignments.

Gustav Mahler |

Bruno Walter, 1910 |

Little meaningful guidance as to the first three decades of Walter's work can be gleaned from surviving accounts, which are bafflingly disparate and seemingly irreconcilable. Thus a report of a 1911 Munich Messiah asserted that he concluded the "Hallelujah Chorus" by accelerating to twice the tempo and "earth-shaking volume," while his first visit to the U.S. in 1923 was dismissed as too controlled, dignified and reserved to satisfy the American temperament. Indeed the confusion would hardly abate even when the first-hand evidence of recordings was available – the 1951 Grove's Dictionary offers that he "excels in sensuous music … though never to excess" while the 1948 Dictators of the Baton slams him for "yielding too often to the urge of overinterpretation. He is so carried away by the music that he cannot resist the temptation [of] permitting the full tide of his feelings to overflow … sometimes inserting uncalled for pauses to heighten suspense, utilizing rubato with too lavish a hand, touching lyric pages with saccharine." Clearly, such reviews reflect the authors' outlooks rather than reliable objective analyses. Walter's own writings are too abstract to be helpful – describing Mahler's outlook (and presumably his own aspirations), Walter cited a "need to seek the eternal" and to be "brimming with life" so as to "seek solutions to insoluble problems" and "speak with particular intensity of the secrets of our existence" – what artist doesn't aspire to that?

In a 1956 interview issued on a Columbia promotional LP to honor his 80th birthday (and assigned catalog number BW 80), Walter claimed "a very vivid recollection" of his first recordings: "I think it was an entr'acte from Carmen; three entr'actes from Carmen … in 1900 in Berlin. Yes, I was at the Opera, the Royal Opera conductor … I was at the tender age of 24. I had conducted concerts already and was invited to make records." Yet despite the accuracy of his other memories late in life this one seems wildly improbable, given the absence of even a single copy of any such disc, any corroboration from documentation, nor mention in others' remembrances. Indeed, recordings of orchestras (as opposed to concert bands) were extremely rare at that time, and with good reason, as the acoustic apparatus (in which the cutting stylus was directly driven by sound gathered by a horn) captured the fundamental notes and most overtones of the human voice, piano and most brass and winds, but not the wider range, broader dynamics and more complex timbre of full ensembles.

An acoustical recording session |

Although generally slighted, if not outright ignored, in most surveys of Walter's career, his acoustical recordings are significant as the earliest tangible evidence of his art. (Indeed, a recent Warner Classics Icon CD box entitled Bruno Walter – The Early Years begins only in the mid-1930s.) Coming as he approached the mid-point of his career as a conductor, they provide a window, albeit a hazy one, to directly glimpse his style that already had enthralled audiences for his first 30 years on the podium, and to bypass reliance on confusing written accounts. Yet they are far from perfect messengers. Even beyond its inherent and unavoidable technical limitations, the acoustic recording process severely challenged conductors (and, for that matter, any musician) who found himself in an alien and forbidding setting. In lieu of a full complement of musicians, the ambience of concert halls to which he was accustomed in shaping a sonic image and an audience whose response was a necessary source of inspiration, he could only use a drastically-reduced number of players crammed into a stiflingly small room to concentrate the sound. He further had to temper dynamic shadings so as to boost quiet passages above the considerable noise floor and avoid loud climaxes that caused distortion, substitute flatulent tubas and bassoons for string basses (and often cellos as well) which recorded as a sonic blur, chop extended works into segments to fit the maximum side length of a few minutes while trying to preserve a sense of continuity and, in the absence of any means of editing, accept technical flaws or execution glitches to avoid having to redo an entire side (which often required reconvening a wholly new session, as there was no means of instant playback to discover lapses before test pressings were made). Under such circumstances, it seems amazing that even a trace of inspiration could emerge. And yet, despite these severe compromises, Walter's acoustical sides present an enticing opportunity to infer the missing first half of his career beyond the vague and often meaningless descriptions of reviews and memoirs.

Walter's first August 1923 sessions began with the simple

Act III Intermezzo and Act IV Prelude of Carmen (so at least his memory of the repertoire was correct) and four overtures – Wagner's Faust, Beethoven's Coriolan, Mendelssohn's Hebrides and Berlioz's Roman Carnival, all in thoroughly credible readings. Heard in order of the matrix numbers, Walter's confidence seems to grow, beginning in the Carmens with cautious pacing and with the melodic line often submerged – understandable for his first venture, although the orchestras, the Berlin Philharmonic and Berlin Staatskapelle (State Opera Orchestra), had ample studio experience. As the sessions progressed he applied increasingly varied tempos and procured more spirited playing. By the time of his next January 1, 1924 session of overtures with the same ensemble more personality emerges – a delightful and propulsive Berlioz Benvenuto Cellini and, remarkably, a rarity: Cherubini's Der Wasserträger, a refreshing break from the warhorses to which recorded repertoire generally adhered at the time, albeit a rather uninspired work and launched here with some painful string intonation. A final set of overtures for Polydor was cut on March 1, 1925 – a buoyant Mozart Cosi fan tutti, a finely-shaded Idomeneo and a sizzling Schumann Manfred (although it's tempting to attribute its driven pace less to an interpretive choice than a necessity to have fit all 10¼ minutes – compared to a normal 12 or so – onto two 12" sides).

Act III Intermezzo and Act IV Prelude of Carmen (so at least his memory of the repertoire was correct) and four overtures – Wagner's Faust, Beethoven's Coriolan, Mendelssohn's Hebrides and Berlioz's Roman Carnival, all in thoroughly credible readings. Heard in order of the matrix numbers, Walter's confidence seems to grow, beginning in the Carmens with cautious pacing and with the melodic line often submerged – understandable for his first venture, although the orchestras, the Berlin Philharmonic and Berlin Staatskapelle (State Opera Orchestra), had ample studio experience. As the sessions progressed he applied increasingly varied tempos and procured more spirited playing. By the time of his next January 1, 1924 session of overtures with the same ensemble more personality emerges – a delightful and propulsive Berlioz Benvenuto Cellini and, remarkably, a rarity: Cherubini's Der Wasserträger, a refreshing break from the warhorses to which recorded repertoire generally adhered at the time, albeit a rather uninspired work and launched here with some painful string intonation. A final set of overtures for Polydor was cut on March 1, 1925 – a buoyant Mozart Cosi fan tutti, a finely-shaded Idomeneo and a sizzling Schumann Manfred (although it's tempting to attribute its driven pace less to an interpretive choice than a necessity to have fit all 10¼ minutes – compared to a normal 12 or so – onto two 12" sides).

In the meantime, in May 1924 Walter cut seven sides in London for Columbia with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra (a complete Wagner Siegfried Idyll and part of Strauss's Tod und Verklärung) but all were rejected. He returned in December for both works, this time successfully. The Strauss seemed a curious choice for acoustical recording, which tended to fuse complex textures of climaxes into a shrill sonic smudge, while lighter scoring, softer passages and sustained notes blended better and emerged considerably more intact. Walter's reading summons rhythmically-precise playing and achieves a keen evolution from the atmospheric opening (abetted by prominent expectant tympani taps) through explosive friction and soothing resolution, and even manages to clarify the climactic strands rather successfully through judicious balances. Comparison with contemporaneous recordings can be instructive. A 1923 HMV recording by Albert Coates and the London Symphony is more richly recorded but reflects a similar interpretive outlook from a conductor known for communicating ardent urgency, whiplash tempos and an overall improvisatory feel. In later life Hermann Abendroth would display comparable personality but his 1922 Polydor set with a "Philharmonisches Orchester" (possibly the Berlin Philharmonic shrewdly hiding its identity behind some excruciatingly crude execution) is far broader (24 minutes vs. Walter's 21) and rather dispassionate, although the final massive climax is effectively wrought.  A further inevitable juxtaposition is with the composer's own 1926 electrical recording with the Staatskapelle, effective in its own right while progressing somewhat more objectively, as expected from a conductor whose restraint was often mistaken for indifference or worse. Alongside these others, Walter's early venture acquits itself quite well.

A further inevitable juxtaposition is with the composer's own 1926 electrical recording with the Staatskapelle, effective in its own right while progressing somewhat more objectively, as expected from a conductor whose restraint was often mistaken for indifference or worse. Alongside these others, Walter's early venture acquits itself quite well.

Walter's Siegfried Idyll is a full-bodied account, ranging from a tender Viennese lilt with tasteful portamento (sliding between string notes) to strong ardent outbursts, although the resonances of the acoustic horn lend strange voicings to some of the chords. For comparison, authentic Wagnerian style of the time can perhaps be gleaned from two early electrical recordings. The composer's son Siegfried could claim a unique connection to the Idyll, as his birth provided the occasion for Wagner to write and first perform it as a combined birthday and Christmas present for his wife. But while never known as a great conductor, Siegfried had a strong pedigree beyond genetics, as he was entrusted with a dozen complete Ring cycles at Bayreuth, the last in 1928. His 1927 HMV recording of "his" Idyll with the London Symphony is far more temperate than Walter's, with a steadier and considerably faster pace. Also apt is a 1929 Electrola Idyll by the Staatskapelle under Karl Muck, a celebrated Wagnerian with a 30-year tenure at Bayreuth (which was interrupted by an unfortunately brief wartime appointment to lead the Boston Symphony – after refusing to precede one concert with the "Star Spangled Banner" he was branded a spy and deported). Although closer to Walter's relaxed tempo, Muck's Idyll, like Siegfried's, is emotionally tepid with little of Walter's plastic shaping of the phrasing.

Walter's most substantial acoustical venture was a Tchaikovsky Symphony # 6 ("Pathétique"), recorded for Polydor in Berlin with the Staatskapelle on March 1, 1925.  Walter's waxing of all ten sides – plus five more for the Mozart and Schumann overtures – in quick sucession testifies to his growing poise in the studio, a confidence further reflected in the maturity of the result, boasting moderated moods, with elastic tempos and smooth integration of the variegated musical impressions. There had been three prior acoustic versions, all from 1923, and they provide a useful comparison. The Staatskapelle under Frieder Weissmann (Odeon) is spread across 12 sides despite a minor trim in the march. Exemplifying his reputation as a reliable (i.e., safe) conductor, Weissmann takes no interpretive risks but rather is weighty, slow and seething, lending the work a consistently tragic aura, opting to drain the waltz of most of its inherent grace and the march of its excitement in favor of a pervasive fatalism. In marked contrast, Henry Wood and the New Queen's Hall Orchestra (Columbia), with heavily-abridged first and second movements, is mostly propulsive and brisk, taming emotional peaks and affording little opportunity for reflection or repose, setting up an effective contrast with an emphatic, dark-toned, brass-heavy finale. Ronald and the Royal Albert Hall Orchestra (HMV) take a more mainstream approach, varying the tempos considerably to reflect the impact of each section. Perhaps owing to his vast studio experience, with the exception of a few untamed brass outbursts in the march, balances are precise, with melodic lines confidently striding atop accompaniment that remains fully audible in its own right. (Walter's Pathétique was its first complete recording, although Ronald's, waxed and issued over a year earlier, came quite close, with only a few trifling excisions in the first and last movements.) A further fascinating account came from Coates and the London Symphony Orchestra (HMV, 1926) with a huge range of tempos that accelerate dramatically for climaxes and decelerate for repose, coupled with dynamic emphases that fully underline the emotional content. Compared to these, Walter occupies a middle, eminently musical ground, embracing the full emotional content of the Pathétique, but without opting for one interpretive extreme to the exclusion of others. Phrases are carefully shaped, the waltz has a distinctive Viennese lilt, the march builds to a thrilling summit and the finale heaves with passion, all achieved with smooth transitions and continuity, in an exemplification of the romantic ideal of not breaking the musical line. Overall, aside from the sound itself, it's a remarkable achievement.

Walter's waxing of all ten sides – plus five more for the Mozart and Schumann overtures – in quick sucession testifies to his growing poise in the studio, a confidence further reflected in the maturity of the result, boasting moderated moods, with elastic tempos and smooth integration of the variegated musical impressions. There had been three prior acoustic versions, all from 1923, and they provide a useful comparison. The Staatskapelle under Frieder Weissmann (Odeon) is spread across 12 sides despite a minor trim in the march. Exemplifying his reputation as a reliable (i.e., safe) conductor, Weissmann takes no interpretive risks but rather is weighty, slow and seething, lending the work a consistently tragic aura, opting to drain the waltz of most of its inherent grace and the march of its excitement in favor of a pervasive fatalism. In marked contrast, Henry Wood and the New Queen's Hall Orchestra (Columbia), with heavily-abridged first and second movements, is mostly propulsive and brisk, taming emotional peaks and affording little opportunity for reflection or repose, setting up an effective contrast with an emphatic, dark-toned, brass-heavy finale. Ronald and the Royal Albert Hall Orchestra (HMV) take a more mainstream approach, varying the tempos considerably to reflect the impact of each section. Perhaps owing to his vast studio experience, with the exception of a few untamed brass outbursts in the march, balances are precise, with melodic lines confidently striding atop accompaniment that remains fully audible in its own right. (Walter's Pathétique was its first complete recording, although Ronald's, waxed and issued over a year earlier, came quite close, with only a few trifling excisions in the first and last movements.) A further fascinating account came from Coates and the London Symphony Orchestra (HMV, 1926) with a huge range of tempos that accelerate dramatically for climaxes and decelerate for repose, coupled with dynamic emphases that fully underline the emotional content. Compared to these, Walter occupies a middle, eminently musical ground, embracing the full emotional content of the Pathétique, but without opting for one interpretive extreme to the exclusion of others. Phrases are carefully shaped, the waltz has a distinctive Viennese lilt, the march builds to a thrilling summit and the finale heaves with passion, all achieved with smooth transitions and continuity, in an exemplification of the romantic ideal of not breaking the musical line. Overall, aside from the sound itself, it's a remarkable achievement.

At the time Walter praised his acoustic recordings (admittedly in a promotional statement) as having made him "greatly pleased. … What sonic beauty in the voices, what pure reproduction and instrumental subtleties, what clarity and fullness in the recording of the orchestral performance." Although he later would dismiss them as "a mechanical device emitting ugly imitative musical noise," his first recordings transcend the constraints of the mechanism to suggest a winning blend of vitality and reflection that would contend for dominance throughout the rest of his career.

[A word about transfers – I truly envy collectors having precious (and often severely worn) original 78s, but the rest of us necessarily must rely on vinyl and now digital transfers of their materials, which range from straightforward copying to running a gantlet of computer programs to attenuate the considerable surface noise, tame resonances, evade scratches, smooth speed instability and extract all available sonic information (but without falsifying it by generating bass and overtones absent from the sources). Taking a proactive approach, Pristine Audio has issued all the Walter acoustics and they sound splendid – hardly hi-fi, but far better than any reproducing instrument of the time could muster. Purists may (and do) quibble over concerns with authenticity, but the result helps to narrow the audible gap between these ancient carriers and their successors, and to better display the unique interpretive possibilities they preserve.]

1925 brought the electrical recording process which vastly enhanced sonic fidelity through sensitive microphones, the ability to mix multiple inputs to adjust balances and a wider frequency range that included genuine bass and higher harmonics. Although the continued use of 78 rpm shellac discs still limited playing time to five minutes per side, full orchestras with all prescribed instruments now could be arrayed normally in resonant halls to emulate a concert experience. But with progress came an unavoidable snag: the rich legacy of an entire generation of acoustical recordings was relegated to obscurity.

the ability to mix multiple inputs to adjust balances and a wider frequency range that included genuine bass and higher harmonics. Although the continued use of 78 rpm shellac discs still limited playing time to five minutes per side, full orchestras with all prescribed instruments now could be arrayed normally in resonant halls to emulate a concert experience. But with progress came an unavoidable snag: the rich legacy of an entire generation of acoustical recordings was relegated to obscurity.

Walter's first electrical sessions in November 1925 focused on excerpts from Parsifal with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra. The first, "Klingor's Magic Garden and the Flower Maidens," boasts rich (if a bit overripe) bass, distinctive timbres and a full dynamic span, led by Walter with assurance and suppleness – and a remarkable degree of continuity despite having to be recorded on four discrete wax masters. (Any disjointedness between sides never would have been noticed at the time, as it would have vanished during the 10+ seconds required to change discs on the manual turntables of the era.)

Along with more overtures and chunks of Wagner, Walter's studio work soon ventured into more substantial repertoire. In November 1926 he cut a complete Beethoven Fifth with the Royal Philharmonic but it was never issued. So instead, his first published symphony performance was the Schumann Fourth recorded in July 1928 with the so-called Mozart Festival (actually the famed Paris Conservatory) Orchestra in which his smooth-flowing interplay of volatile energy and classical order seems to exemplify the very essence of Romanticism. (His 1938 remake with the Vienna Philharmonic, also for HMV, is far more mellow with moderated tempos and lacks the thrilling surges of insistent passion – as well as the finale repeat – of the earlier version.) At the end of his life Walter reportedly was planning a set of all four Schumann symphonies, but we only have one other – an austere, prosaic 1941 NY Philharmonic Third (Columbia) with a downright somnolent Scherzo.

Mozart ~ Walter devoted much of what would become his final decade in Europe to documenting his cherished Viennese composers, beginning with Mozart.

A rarity – Walter at the keyboard |

Haydn ~ Of the six Haydn symphonies he ultimately would record, Walter cut four in 1937-1938 for Victor. Ironically, they reverse the trend with his Mozart, displaying far more style with British and French orchestras than with the Vienna Philharmonic. Most depressing is # 100 with a stodgy Allegro and no "Turkish" percussion battery nor any other hint of drama to enliven the Allegretto (and thus robbing the work of the essence conveyed by its very nickname – the "Military"). The other Vienna symphony, # 96, seems too suave and patient to deliver Haydn's trademark wit and vivacity. In contrast, # 92 (with the Paris Conservatory) is animated with a rip-roaring finale and # 86 (London Symphony) bursts with athletic vitality, both possibly reflecting Walter's relief from having recently escaped the Anschluss to more welcoming countries.

Beethoven ~ With the 1926 Fifth unreleased,

Walter Gieseking and Joseph Szigeti |

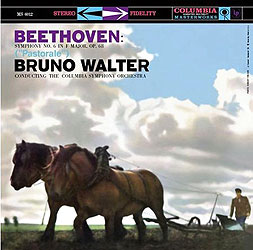

1936 brought Walter's only pre-war Beethoven symphony recording – an HMV "Pastoral" with the Vienna Philharmonic. By then, even aside from two complete acousticals led by Hans Pfitzner (1923, Polydor – mostly relaxed and lovely) and Frieder Weissmann (1924, Parlophone – bursting with enthusiasm and character), collectors had a choice of at least six competing versions in a wide range of interpretations – Felix Weingartner/Royal Philharmonic (1927, Columbia – quickly-paced); Franz Schalk/Vienna Philharmonic (1928, HMV – simplified steady tempos but subtle shifts to underline the "Scene By the Brook"); Serge Koussevitzky/Boston Symphony (1928, Victor – patrician refinement); Max von Schillings/Staatskapelle (1929, Parlophone – relaxed but heavily inflected); Pfitzner (a first remake)/Staatskapelle (1930, Polydor – contemplative and pliant); and Paul Paray/Colonne Orchestra (1934, Columbia – extremely swift). 1937 would bring two more – Toscanini/BBC (EMI – fundamentally propulsive but with enough elasticity to avoid a sense of mechanical rigidity) and Willem Mengelberg/Concertgebouw (Telefunken – bursting with deeply personal and fascinating emphases, balances, ornaments, dynamics and phrasing).

Amid this bounty, Walter's account acquits itself quite well – refined, plush, secure and exuding a warmth and sincerity that echoes the composer's feelings in conveying the wonders of his beloved nature, and noticeably slower recapitulations as though to invoke the heartfelt ease of an idealized ingenuous peasant life of rustic dances and heartfelt thanksgiving – and yet, atypically for him, Walter summons a potent thunderstorm with pounding tympani and slashing strings.

Amid this bounty, Walter's account acquits itself quite well – refined, plush, secure and exuding a warmth and sincerity that echoes the composer's feelings in conveying the wonders of his beloved nature, and noticeably slower recapitulations as though to invoke the heartfelt ease of an idealized ingenuous peasant life of rustic dances and heartfelt thanksgiving – and yet, atypically for him, Walter summons a potent thunderstorm with pounding tympani and slashing strings.

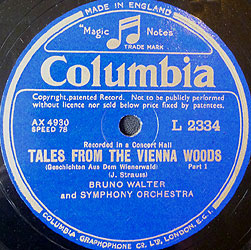

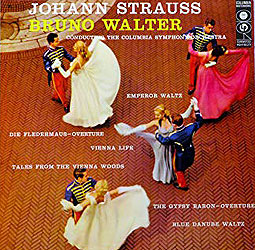

Strauss ~ It might seem reasonable to assume that a collegial conductor's results would largely depend upon the character of the orchestras he led. Walter's first recordings of Strauss – Johann Jr., not Richard – invite a fascinating test of that theory. Results from the same orchestra turned out quite differently – twice. A January 1929 session with the Staatskapelle produced two widely disparate outcomes – a crisp, energetic Fledermaus Overture with well-defined sections along with a tender Wiener Blut waltz with exquisitely delicate string portamento (sliding between notes). Similar inconsistency arose in an April 1929 session with an unnamed British orchestra (possibly the London Philharmonic?) – Tales From the Vienna Woods is graced with elegance while the Gypsy Baron Overture is bland and impersonal. Nor did orchestras always yield outcomes predicted by their reputations – while a 1930 Berlin Philharmonic Roses From the South is expectedly thick and earth-bound, in a 1937 Vienna Philharmonic Emperor Waltz we hear little of the effortless, irrepressible rhythmic vitality that so many others induced from that ensemble in Strauss – not just Viennese natives like Kleiber and Krauss, but outsiders like Szell, Knappertsbusch and even Furtwängler.

Brahms ~ As for another pillar of Viennese Romanticism, Walter cut three of the four Brahms symphonies during this era, all for HMV/Victor, beginning with a 1934 Fourth with the BBC Symphony. As with the "Pastoral", he entered an already populated field but here faced a more daunting challenge – a recording by a conductor who knew the composer and left a compelling account from which to infer Brahms's own taste – although Max Fiedler (1859 – 1939) only took up conducting after Brahms died, the composer admired his piano playing and they became close friends. Fiedler's 1930 HMV recording with the Berlin State Opera Orchestra is impulsive and mystical, constantly alive with emphatic phrasing, tempo extremes and bold expressive touches that announce a partnership between composer and interpreter and a deeply personal journey to find passion and inject a sense of instability beneath the objective surface of the score.

Yet in marked contrast, a 1938 EMI recording with the London Symphony by Felix Weingartner (1863 - 1942), the only other conductor on record who had worked with Brahms, is fundamentally steadfast, restrained, subtly inflected, elegant and shorn of rhetoric, but its authenticity can be discounted, as his approach had fully evolved during the intervening half-century from his deeply personal proactive manner of the late 1800s (Walter branded him as having a "fiery temperament") to his pioneering of the modern objective style that came to dominate the 20th century. Even so, Walter seems to bridge the interpretive gap between the Fiedler and Weingartner recordings – the first two movements begin gently and relaxed but pick up vast speed and energy as they unfold, the third zips by nearly a minute faster than Toscanini's and, in a herald of Furtwängler's astounding concert readings, the finale wallows in German weight before a rip-snorting wrap-up. Although balances in the softer sections tend to obscure the melodic lines, Walter's sensitive phrasing is wondrous throughout. The BBC orchestra was only four years old at the time, and thus perhaps more amenable to bold leadership than the century-old, self-governing and chauvinistic Vienna Philharmonic, with which Walter recorded the Third in 1937 and the First in 1938. Both glow with the famed orchestra's burnished sound and the finales spring to life, but elsewhere the leadership tends to sound more dutiful than inspired.

Yet in marked contrast, a 1938 EMI recording with the London Symphony by Felix Weingartner (1863 - 1942), the only other conductor on record who had worked with Brahms, is fundamentally steadfast, restrained, subtly inflected, elegant and shorn of rhetoric, but its authenticity can be discounted, as his approach had fully evolved during the intervening half-century from his deeply personal proactive manner of the late 1800s (Walter branded him as having a "fiery temperament") to his pioneering of the modern objective style that came to dominate the 20th century. Even so, Walter seems to bridge the interpretive gap between the Fiedler and Weingartner recordings – the first two movements begin gently and relaxed but pick up vast speed and energy as they unfold, the third zips by nearly a minute faster than Toscanini's and, in a herald of Furtwängler's astounding concert readings, the finale wallows in German weight before a rip-snorting wrap-up. Although balances in the softer sections tend to obscure the melodic lines, Walter's sensitive phrasing is wondrous throughout. The BBC orchestra was only four years old at the time, and thus perhaps more amenable to bold leadership than the century-old, self-governing and chauvinistic Vienna Philharmonic, with which Walter recorded the Third in 1937 and the First in 1938. Both glow with the famed orchestra's burnished sound and the finales spring to life, but elsewhere the leadership tends to sound more dutiful than inspired.

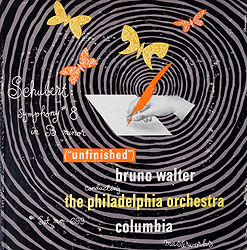

Schubert ~ For the most Viennese Romantic composer (the only one born and raised there) Walter bestowed one of his finest recordings with its resident orchestra – a Schubert "Unfinished" Symphony (Vienna Philharmonic, 1936, HMV) of total commitment and immersion, ideally balanced between tension and ease, turmoil and serenity, resolute headway and brooding thoughts, all integrated with a magical organic flow and natural breath, in one of its finest performances on record. By comparison, Walter's "Great" Symphony # 9 with the London Philharmonic (1938, HMV) barely lives up to its name, sounding rather unfocused and largely devoid of weight, much less charm or nuance. (Curiously, a filler of the Rosamunde G-Major ballet music cut at the same session, although admittedly posing far fewer interpretive challenges, is considerably more delicate and vivacious, while a companion Rosamunde E-minor ballet is nearly as mundane as the "Great.")

Politically naïve, Walter might not have realized it at the time, but he closed the first, longest and deepest-rooted phase of his career with three superlative recordings with the Vienna Philharmonic that would serve not only as touchstones of his art up to that point but as souvenirs of the Europe in which he was nurtured and lionized, and to which he would return years later, but only as an occasional guest.

Wagner: Die Walküre – Act I – Lauritz Melchior, Lotte Lehmann, Emanuel List (June 20-22, 1935, HMV) – For most of his professional life Walter was best known as a conductor of opera. Yet while he recorded overtures, instrumental interludes and a few aria accompaniments he never led a complete opera in the studio.

Lauritz Melchior and Lotte Lehmann |

Mahler: Das Lied von der Erde – Kerstin Thorborg, Charles Kullman, Vienna Philharmonic (May 24, 1936, Columbia) – Equally remarkable yet even more meaningful was this very first recording of Mahler's penultimate work. Having not only trained under Mahler but becoming his closest professional colleague and acolyte, Walter was entrusted with the score of Das Lied von der Erde and led its posthumous world premiere.  A quarter-century later, Mahler was still remembered as an influential conductor but barely recalled as a composer. Das Lied apparently was deemed too obscure to risk the expense of studio sessions or commercial release, and so its 14 sides were cut live at a concert by the newly-formed Mahler Society to commemorate the 25th anniversary of the composer's death and sold on a subscription basis. Despite inevitable blemishes, the result is an intensely human document, propelled by a marvelous feeling of spontaneity that eludes all subsequent recordings (including Walter's own two). Orchestra and vocalists dig into their notes with wholehearted abandon, often taking substantial liberty with the prescribed rhythm. Both singers project vast sincerity and even vulnerability by holding their vibrato to a minimum, and in the process avoid any suggestion of stylized opera or refined art singing. While the somewhat crude sound obscures some of the detail and weakens the delicacy of the ethereal ending, the instrumental choirs compensate by standing out with vivid detail that highlights the inventiveness of Mahler's scoring. Although relatively fleet, Walter's pacing never seems rushed, but rather vibrant and lucid. As Walter wrote at the time, he tried to create a first-time experience: "The supreme value of Mahler's work lies not in the novelty of it being intriguing, daring, adventurous or bizarre but rather in the fact that this novelty was transfused into music that is beautiful, inspired and profound."

A quarter-century later, Mahler was still remembered as an influential conductor but barely recalled as a composer. Das Lied apparently was deemed too obscure to risk the expense of studio sessions or commercial release, and so its 14 sides were cut live at a concert by the newly-formed Mahler Society to commemorate the 25th anniversary of the composer's death and sold on a subscription basis. Despite inevitable blemishes, the result is an intensely human document, propelled by a marvelous feeling of spontaneity that eludes all subsequent recordings (including Walter's own two). Orchestra and vocalists dig into their notes with wholehearted abandon, often taking substantial liberty with the prescribed rhythm. Both singers project vast sincerity and even vulnerability by holding their vibrato to a minimum, and in the process avoid any suggestion of stylized opera or refined art singing. While the somewhat crude sound obscures some of the detail and weakens the delicacy of the ethereal ending, the instrumental choirs compensate by standing out with vivid detail that highlights the inventiveness of Mahler's scoring. Although relatively fleet, Walter's pacing never seems rushed, but rather vibrant and lucid. As Walter wrote at the time, he tried to create a first-time experience: "The supreme value of Mahler's work lies not in the novelty of it being intriguing, daring, adventurous or bizarre but rather in the fact that this novelty was transfused into music that is beautiful, inspired and profound."

While Walter undoubtedly had matured and evolved over the quarter-century that had elapsed since he explored the work with its composer, this first recording, even aside from its intrinsic splendor, boasts unique authenticity. Mahler had written to Walter: "I know of no one who understands me as well as I feel you do and I believe I have entered deep into the mine of your soul." Mahler's widow Alma also credited Walter with a full understanding of her husband and wrote: "After [Mahler's] death, Walter's great and exalted art was at his service. He mastered its every subtlety … and he took the spirit of Mahler's work as the keystone of his own work as an interpretive musician." Mahler's own conducting reportedly was full of tension, poised uneasily between precision and clarity vs. passion and spontaneity. Walter recalled it as both tyrannical intimidation and passionate stimulation. Mahler never cut any records but did make four piano rolls in 1905 in the Welte-Mignon process that captured not only the notes but their nuance and provides an uncannily accurate reproduction of the quality of the original playing. Yet his rolls are full of quirky tempos and largely disregard the many detailed expressive and dynamic felicities specified in the scores. Perhaps the rolls were an anomaly – Mahler never was deemed a virtuoso pianist and may have been unnerved by his first (and only) exposure to the demands of the unfamiliar machinery. (Although after the playback Mahler wrote in the studio guest book: "In astonishment and admiration," his reference may have been to the marvels of the technology rather than to the artistic value of the result.)

While we never will know how Mahler would have led Das Lied, Walter's 1936 concert seems to exemplify reminiscences of the composer's own outlook. At the same time, it is our earliest document of Walter's radiance in leading live performances, not always captured by his studio work.

While we never will know how Mahler would have led Das Lied, Walter's 1936 concert seems to exemplify reminiscences of the composer's own outlook. At the same time, it is our earliest document of Walter's radiance in leading live performances, not always captured by his studio work.

Mahler: Symphony # 9 (Vienna Philharmonic, January 16, 1938, HMV) – So, too, with Mahler's last completed work, which also had been given its posthumous world premiere by Walter, who recorded it for the first time in concert (along with the Adagietto of Mahler's Fifth Symphony which avoids wallowing in the sentimental glop of so many other readings). At the risk of waxing a bit too poetic, I cannot hope to better André Tubeuf's magnificently moving tribute and historical perspective: "It was final testimony of that sensitive splendor of sound, emotional and noble at the same time, and of that sovereign freedom of rhythm which, as an improvisation, all the great exiles had had as long as the soil of Europe was beneath their feet and the sky of liberty above their head and which they would no longer attain. … We hear a whole world that is on the march, storms which are awakening or dying down, the terrible poetry of evolution, objective and indifferent to Man. … It is this message that Mahler entrusted to his music and Walter received from him and passed on to the orchestra that was the rightful heir to it and had been chosen from amongst all others for this mission. Thus both Mahler and Walter were able to travel to the end of the road." Not only was the Ninth Mahler's farewell to the world, but this particular Ninth served as Walter's own farewell – his last concert before the Nazi invasion ripped him from his native soil. It preserves for one final time a world of music that was about to vanish.

Mozart operas – Fortunately, we have two whole Mozart operas from Walter's last season at the Salzburg Festival – an August 19, 1937 Marriage of Figaro with Ezio Pinza (Figaro), Mariano Stabile (Count Almaviva), Aulikki Rautawaara (Countess Almaviva), Esther Réthy (Susanna) and Jarmila Novotná (Cherubino) and an August 2, 1937 Don Giovanni with Pinza in the title role and Elisabeth Rethberg (Donna Anna), Luise Helletsgruber (Donna Elvira), Margit Bokor (Zerlina) and Dino Borgioli (Don Ottavio). Both were preserved with the short-lived Selenophone system which exposed an optical soundtrack on 8mm film that enabled continuous takes but posed problems with pitch stability, volume levels and a nitrate base that was both highly flammable and subject to severe deterioration.  As summarized by Andreas Kluge, Walter credited Mahler with transcending the rococo image of Mozart of daintiness and academic dryness to reveal dramatic sincerity and a wealth of characterization, uncovering layers of compelling truth behind a screen of charm. Consequently, Walter sought an ideal balance of dramatic expression without impairing its musical splendor. I'll gladly leave evaluation of the singing to true opera buffs but, as for Walter, John Quinn on Musicweb calls the Figaro energized: "The recitatives fairly fizz and the pacing of the arias and ensembles is always convincing. This is really involving, dramatic conducting by a true man of the theatre. … Just occasionally some listeners may feel that the performance is just a bit too driven in the heat of the moment and that a little more relaxation might have been welcome. For myself I can only say that I found myself swept along by the thrust and conviction of the whole thing." Much the same can be said for Walter's Giovanni, which explores the darker side of human foibles.

As summarized by Andreas Kluge, Walter credited Mahler with transcending the rococo image of Mozart of daintiness and academic dryness to reveal dramatic sincerity and a wealth of characterization, uncovering layers of compelling truth behind a screen of charm. Consequently, Walter sought an ideal balance of dramatic expression without impairing its musical splendor. I'll gladly leave evaluation of the singing to true opera buffs but, as for Walter, John Quinn on Musicweb calls the Figaro energized: "The recitatives fairly fizz and the pacing of the arias and ensembles is always convincing. This is really involving, dramatic conducting by a true man of the theatre. … Just occasionally some listeners may feel that the performance is just a bit too driven in the heat of the moment and that a little more relaxation might have been welcome. For myself I can only say that I found myself swept along by the thrust and conviction of the whole thing." Much the same can be said for Walter's Giovanni, which explores the darker side of human foibles.

And ... Banned from Germany and no longer welcome in Austria (and to underline the message, his daughter was arrested and detained there), Walter was offered and accepted citizenship by France, where in May 1938 he recorded with the Paris Conservatory Orchestra a rather heavy-handed Handel Concerto Grosso, the Haydn Symphony # 92 and remakes of the Freischutz and Fledermaus Overtures. The following May came a far more interesting Berlioz Symphonie Fantastique. Interpretively, it opts for a middle ground amid the classicism of Weingartner/London Symphony (Columbia, 1925), the near hysterical melodrama of Meyrowitz/Paris Symphony (Columbia, 1934) and the casual "French" sound of Pierné/Colonne Orchestra (Odéon, 1928), but its greater value lies in its exploitation of extremely soft dynamics and the orchestral timbres that, according to Walter, Mahler so admired in Berlioz, as well as its use for the Dies Irae dirge of the deep c-c-G bells that Berlioz preferred in the finale to produce a darkly dissonant and chilling atmospheric impact rather than the terse gongs commonly found in orchestral arsenals and used in nearly every other recording. Marsh asserts that Walter remained fond of this recording as a moral example of resisting others' temptation to treat it as a display piece.

One further artifact from this era is a blend of geography and culture: a Mozart Requiem recorded live on June 29, 1937 at the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées in Paris but with Austrian performing forces – the Vienna Opera Chorus and Vienna Philharmonic.

Horowitz and Walter |

Between losing his German homeland and his Austrian substitute Walter concertized throughout free Europe. One the very few documents of a Walter pre-war concert apart from the Vienna Philharmonic is an extraordinary February 20, 1936 broadcast of the Brahms Piano Concerto # 1 in d minor with Vladimir Horowitz and the Amsterdam Concertgebouw Orchestra. Horowitz had first played the Brahms with Toscanini and the New York Philharmonic a year earlier; an extant recording clocks in at a mere 39½ minutes (compared to an average 48 or so), is brutally hard-driven and the solos sound rigid and perfunctory. Walter's concert is nearly as swift in its timing but within the same fundamental propulsive approach boasts vastly greater breadth and respite. Of course, it's unfair to generalize from the evidence of a single recording outside the confines of the studio and away from the lustrous sound of the Vienna Philharmonic, and especially when accompanying (and perhaps accommodating) a soloist of headstrong brilliance with an orchestra accustomed to the bold personality of Willem Mengelberg, its permanent conductor. (Walter's only other pre-war Concertgebouw concert recording of which I'm aware is a February 2, 1937 Ravel Concerto in D in which he provides dark, forceful support for (while deferring to the prerogatives of) Paul Wittgenstein, the pianist for whom it was written.) Even so, in retrospect the sheer visceral excitement of the Brahms clearly pointed toward the next phase of Walter's extraordinary career when he would depart so radically from all that had come before.

Walter had first visited the U.S. in 1922 and had been "enraptured from the first moment" he saw California, "captivated by the climate, the light, the colors and the landscape" as well as the mixture of beauty and artifice in Hollywood. After losing his third European home upon the annexation of France, he joined a huge wave of European exiles who combined their brilliant artistic backgrounds with fresh opportunities to establish a colony of musical excellence in Los Angeles.

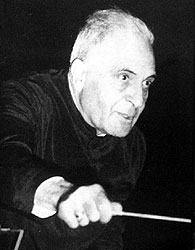

Toscanini and "his" NBC Symphony Orchestra |

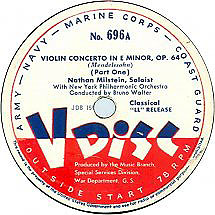

The broadcasts were transcribed on 16" 33 1/3 rpm discs using the then-standard 78 groove width rather than the microgroove technology later adopted for commercial LPs. While RCA Victor officially released some of the Toscanini items, all of Walter's remain cached in archives. Through a combination of off-air home recordings and less legitimate means several individual works found their way onto pirate LPs and CDs. Collectors now have assembled all ten complete concerts which afford us an extraordinary opportunity to assess this key phase of Walter's career in its entirety, including several major works absent from his studio output. (And no, I don't feel even the slightest twinge of guilt over the liberation of such fabulous cultural treasures when the legal keepers refuse to make our musical heritage available for scholarship, research or just sheer enjoyment.)

Walter saw his NBC broadcasts as "not an escape from world affairs but an active way to oppose tyranny with a message of hope and promise to all mankind." Of the 35 works he programmed, ranging from pleasant diversions (Mozart Minuets and German Dances) to the monumental (14 symphonies), only a few disappoint – a plodding, rigid Berlioz Rákóczy March and a Ravel Rhapsodie espagnol that generates little sensuality, color or atmosphere. Two others are similar to his prior recordings – a Schumann Fourth with identical timings and only slightly more oomph than his 1938 London Symphony recording, and a Berlioz Symphonie Fantastique (with those same deep bells) that seems less energetic overall than his 1939 Paris 78s and comes alive only at the very end. (The latter's striking similarity to a 1954 New York Philharmonic concert suggests a fundamentally consistent view of this particular work, although perhaps Walter simply was having a rare off-night at NBC – indeed, the Corsair Overture that launched the same all-Berlioz concert is mellow overall until a frenetic wrap-up and thus not convincingly integrated.) Nearly all the rest of his NBC performances display an outpouring of intense interpretive invention and sheer passion unique in Walter's career.

The First Concert – Walter began the series on March 11, 1939 with a rather modest all-Mozart program that seems to function as both a personal showcase and a sign that for the next month he would be bending Toscanini's orchestra to his own tastes.  First came a warm-up for the more challenging pieces ahead: the Divertimento in B-Flat, K. 287 (minus its first minuet), in a big-band setting for the full ensemble played with both spirit and geniality – and some precarious ensemble that suggests meager rehearsal, or perhaps just unfamiliarity with a new conductor. (Toscanini would program the same work – the only piece of Mozart's extensive social music he ever played – in a 1946 reading with greater precision and firmer tempos that could be heard as stylish in the sense of Mozart needing no embellishment.) Next, in a display of versatility that Toscanini couldn't match, came the Piano Concerto # 20 in d featuring Walter as both soloist and conductor, swifter overall than his 1937 Vienna Philharmonic recording and with greater differentiation between pressing the orchestral portions and relaxing for his solo sections. The concert closed with the Symphony # 40, still quite muscular but with more moderate pacing and far better integration and attention to refined details than the 1929 Staatskapelle set (and far more pliant than Toscanini's own taut and rather rigid 1939 NBC recording).

First came a warm-up for the more challenging pieces ahead: the Divertimento in B-Flat, K. 287 (minus its first minuet), in a big-band setting for the full ensemble played with both spirit and geniality – and some precarious ensemble that suggests meager rehearsal, or perhaps just unfamiliarity with a new conductor. (Toscanini would program the same work – the only piece of Mozart's extensive social music he ever played – in a 1946 reading with greater precision and firmer tempos that could be heard as stylish in the sense of Mozart needing no embellishment.) Next, in a display of versatility that Toscanini couldn't match, came the Piano Concerto # 20 in d featuring Walter as both soloist and conductor, swifter overall than his 1937 Vienna Philharmonic recording and with greater differentiation between pressing the orchestral portions and relaxing for his solo sections. The concert closed with the Symphony # 40, still quite muscular but with more moderate pacing and far better integration and attention to refined details than the 1929 Staatskapelle set (and far more pliant than Toscanini's own taut and rather rigid 1939 NBC recording).

Unusual Programming – Although largely adhering to standard repertoire of the classical and romantic eras, beyond the Mozart Divertimento Walter led two baroque-era G-Minor concerti grossi. His Corelli "Christmas Concerto" is typical for the time – swelled and romanticized with heavy bass, thick textures, broad dynamics, wide vibrato and minimal grace. Handel's Op. 6 # 6 is slightly more animated, but still thick, dark and hefty overall (and further weighed down by a prominent piano continuo). D'Indy's rarely-heard but colorful Ishtar (notable for its inverse structure, in which the theme emerges only at the end after passing through variations) seems inert compared to its far more vital (and only pre-stereo) 1945 recording by Pierre Monteux and the San Francisco Symphony. A final oddity is a straight-forward reading of Daniel Gregory Mason's Old English Folk Song Suite. Although he led his share of then-recent works toward the dawn of his career, Walter had no stomach for truly modern music – he called atonality "as senseless as a rebellion against the laws of physics" and an effort to subvert the soul with intellect; for that matter, he snubbed jazz as insulting, debasing, a caricature of music and appealing to lower instincts. Mason's pleasant ramble was contemporary only in the sense of having been written in 1934, as it reflected the style of an earlier century. As Mason was American, perhaps Walter programmed it as a patriotic gesture toward his newly adopted country.

Disjointed – Just to get the few other letdowns out of the way …  A Beethoven Symphony # 1 and a Schubert Symphony # 5 both would seem especially amenable to Walter's typical glowing warmth and their unassuming structures would seem to invite steadfast readings, and yet the outset of the Beethoven is torn by seemingly random propulsion and inertia before settling down and the modest Schubert begins gruff and thick but ends with an assertive Scherzo and a hectic finale. Perhaps rather than a disappointment or lapse they signal that for his NBC concerts Walter was not content to fall back on his natural inclinations but was seeking a new path, had already absorbed some of the American spirit of daring and invention, and was prepared to assume risks that until now had lain dormant in his artistic outlook.

A Beethoven Symphony # 1 and a Schubert Symphony # 5 both would seem especially amenable to Walter's typical glowing warmth and their unassuming structures would seem to invite steadfast readings, and yet the outset of the Beethoven is torn by seemingly random propulsion and inertia before settling down and the modest Schubert begins gruff and thick but ends with an assertive Scherzo and a hectic finale. Perhaps rather than a disappointment or lapse they signal that for his NBC concerts Walter was not content to fall back on his natural inclinations but was seeking a new path, had already absorbed some of the American spirit of daring and invention, and was prepared to assume risks that until now had lain dormant in his artistic outlook.

The Triumphs – Walter seemed to have saved his peak inspiration (and his players' focus and stamina) for the major works with which he concluded most of his NBC concerts with an abundant infusion of vibrant energy that stands in striking contrast to his prior recordings (and the NBC's concerts with its primary conductor).

- Mahler: Symphony # 1 – Walter's Vienna concerts explored the late, autumnal Mahler, and here we have our first document of his approach to Mahler's more youthful work (this one written at 28). Although Walter was already 63, he embarks with athletic vigor and eager versatility in a winning fusion of brash energy and poetic sensitivity. The second movement in particular, thick with peasant lustiness amid recollections of Viennese finesse, asserts the power of Walter's personality to extract from Toscanini's orchestra such subtle infusions well beyond the Maestro's interpretive arsenal. The finale seethes with probing expectation and robust vitality in what perhaps is our most credible indication of how Mahler himself viewed his early work.

Bruckner: Symphony # 4 – Although he became known as a Bruckner specialist, Walter came to Bruckner relatively late in life. This, our first evidence of his approach, is altogether stunning, a deeply personal interpretation a universe apart from any other, including Walter's own later renditions. The first movement veers wildly from frenetic climaxes to extreme torpor, tearing the texture with blaring brass and ripping the structure apart with distinct sections and a disregard of preserving the basic pulse. Next the Andante radically shifts gears, repressing passion with mild, slow, patient surges until a frantic climax. The Scherzo is furiously driven, without regard to the orchestra's utter inability to keep pace, relieved temporarily by a tender trio. After all that, the finale seems surprisingly moderate, as though the music itself reels with exhaustion.

Tchaikovsky: Symphony # 5 – Walter took little interest in Tchaikovsky and that seems a shame; after the acoustic "Pathétique" this is our only Walter recording of a Tchaikovsky symphony and it's terrific, bracketed by an altogether gripping first movement smoothly balanced between intense emotional underlining and lovely lyricism and a dignified finale that relentlessly holds back the floodgates to accentuate a final burst of energy. Walter's considered restraint seems all the more extraordinary when compared to a turbulent 1941 concert with the same orchestra in which Stokowski constantly distends the dramatic content of the music to the breaking point – more immediately striking, but perhaps ultimately less satisfying.

Strauss: Don Juan and Death and Transfiguration – The score of Don Juan is so fully characterized as to require little creative input for total effect,

and Walter conveys the full panoply of its shifting emotions. By contrast, Death and Transfiguration suddenly heaves between wallowing in despair and exploding in feverish ecstasy, and Walter accentuates a super-charged account of the sudden climaxes, the contrast between the disparate sections far more magnified than in his acoustic recording.

and Walter conveys the full panoply of its shifting emotions. By contrast, Death and Transfiguration suddenly heaves between wallowing in despair and exploding in feverish ecstasy, and Walter accentuates a super-charged account of the sudden climaxes, the contrast between the disparate sections far more magnified than in his acoustic recording.Brahms: Symphony # 1 – Unfortunately, the only transfer I've heard of this performance is soured with excessive wow (severe speed variation), possibly a defect in the original that would require a sophisticated computer program to rectify. Even so, despite the compromised sound, the outer movements emerge as far more vital than in Walter's earlier 78 set and far more deeply inflected and with far more visceral excitement than the steadfast focus and precision of Toscanini's own 1940 NBC concert.

Schubert: Symphony # 9 – Here, too, the differences are striking between this vibrant, engaged reading and both Walter's routine prior studio recording and Toscanini's steady, focused if rather impersonal 1938 NBC concert rendition. If the second movement and finale seem tame and somewhat conventional with relatively steadfast pacing, it's only by comparison with the compelling sense of architecture that emerges from the opening movement's smooth transitions among Walter's extreme pacing of the assertive and reflective portions; a reflection of that approach adds considerable and uncommon interest to the Scherzo.

Haydn: Symphonies #s 86 and 92 – As though to display Haydn's variety, as well as his own versatility in repertoire that few took seriously at the time, Walter provides vastly different views of these two Haydn symphonies. # 92 is thoroughly stylish and magnificently well-integrated, beginning with an Allegro spiritoso that's spirited enough yet suitably delicate, proceeds to an Adagio cantabile that displays careful dynamic control for structural definition and a Menuetto that irrepressibly invites visions of dancing that, in turn, ends with a finale bursting with vigor and drive. # 86, though, reflects Haydn's wicked humor by building rather teasingly with a lively opening, a lush Capriccio and an emphatic but patient Menuetto that barely prepare us for the finale that startles as harsh, adamant, rough-hewn and furiously-driven.

Lest the foregoing comparisons with roughly contemporaneous NBC concerts led by Toscanini point to a consistent fundamental difference (and perhaps Walter's intent to underscore his individuality from a preeminent but intolerant rival, who reportedly once walked out of a Walter rehearsal in disgust), we should note that some of their performances were strikingly similar, including a Mozart Symphony # 35 and a Brahms Symphony # 2, both of which emerge as only slightly more personal and just a bit more rousing under Walter's baton. Yet the dearth of such instances suggests mere coincidence rather than any degree of conscious emulation.

It's tempting to credit Walter's remarkable if brief output with the NBC to some unique chemistry between him and the orchestra. On the one hand the musicians might have welcomed a respite from the dictatorial Toscanini. At the same time, being relatively newly-formed, they had not yet calcified into a uniform "sound." Yet we have a handful of Walter's concerts from the same period with other ensembles that display much of the same distinctive fervor. The finale of a 1942 New York Philharmonic Bruckner Symphony # 8 startles with its unbridled discontinuity that attacks and dismantles the patient edifice built up in the earlier movements.  A 1943 NY Philharmonic Haydn Symphony # 88 scrambles through a delirious 2'50" finale (a full half-minute faster than Toscanini's 1938 NBC reading). A 1941 Philharmonic Debussy La mer eschews wild tempos but surges with bold splashes of color that transcend the dismal sound. And a Dvorak "New World" Symphony from a 1942 Standard Symphony Orchestra concert in Los Angeles begins with intense drama as slashing climaxes smoothly glide into exquisite tenderness, the Scherzo bursts out after the calming lull of the soothing Largo, and the finale follows clipped opening chords with grim exhaustion (grounded by pronounced but muffled tympani) until a final gallop at the end. A Tchaikovsky Romeo and Juliet Overture from the same concert projects extreme contrast between the lyrical and adrenalized sections. (Unfortunately we are at a loss to evaluate the converse situation – comparing Walter's NBC concerts with those led by other guest conductors – since so few are available; we do have some in the early 1950s by Cantelli, but that was a decade later and he was Toscanini's protégé and thus not unexpectedly followed in the Maestro's proverbial footsteps.)

A 1943 NY Philharmonic Haydn Symphony # 88 scrambles through a delirious 2'50" finale (a full half-minute faster than Toscanini's 1938 NBC reading). A 1941 Philharmonic Debussy La mer eschews wild tempos but surges with bold splashes of color that transcend the dismal sound. And a Dvorak "New World" Symphony from a 1942 Standard Symphony Orchestra concert in Los Angeles begins with intense drama as slashing climaxes smoothly glide into exquisite tenderness, the Scherzo bursts out after the calming lull of the soothing Largo, and the finale follows clipped opening chords with grim exhaustion (grounded by pronounced but muffled tympani) until a final gallop at the end. A Tchaikovsky Romeo and Juliet Overture from the same concert projects extreme contrast between the lyrical and adrenalized sections. (Unfortunately we are at a loss to evaluate the converse situation – comparing Walter's NBC concerts with those led by other guest conductors – since so few are available; we do have some in the early 1950s by Cantelli, but that was a decade later and he was Toscanini's protégé and thus not unexpectedly followed in the Maestro's proverbial footsteps.)

So what did happen to so radically change Walter's musical personality?

Walter generally embraced a rose-tinted view of politics, society, colleagues and family, relying upon music as a force for human betterment by striving for consonance amid dissonance, radiating optimism and lifting us above the mundane to a higher plane of spiritual existence. Yet for once his self-imposed serenity may have been shattered, as he was going through the roughest patch of his life. He had tried to accommodate anti-Semitism from the outset of his career when he changed his surname and converted to Catholicism (as had Mahler) in the hope of mollifying cultural gatekeepers but to increasingly little avail, as the German press taunted by referring disparagingly to his given name of Schlesinger and questioning his racial fitness to convey "true" German art. As the Nazis solidified their grip on Europe, he was banished from concert halls in all the cultural centers of the continent where he focused his career. Of the three women closest to him, one daughter was murdered by her jealous husband, the other was harassed by the police and his wife slipped into permanent depression. He was warmly welcomed in America and claimed membership in a "community of human spirit beyond centuries and mundane boundaries – an invisible church that had sheltered me from the innumerable attacks with which the events of daily life shake man's power of resistance. … Music proclaims in a universal language what the thirsty soul of man is seeking beyond this life." And yet he was a spiritual refugee, torn away from the physical and cultural comfort of all he had known and adrift in a new and uncertain world. Surely Walter felt some of the same internal turmoil as Furtwängler, who poured into his matchless Wartime concerts his internal agony over the dissolution of the culture in which he had been so deeply immersed and whose interpretations transmuted the collision of art, politics and morality into music of unprecedented power. Perhaps in light of the Nazis' seemingly invincible grip over Europe Walter feared for the future of Western civilization and at the same time absorbed some of the intrepid brashness that typified the art of his adopted country.

There's also something special about concerts.  At first it seems counterintuitive – shouldn't an artist be willing to take more risks in the studio where miscalculations or gaffes can be redone (or, in the tape and digital eras, repaired with patches from parallel takes) than in the concert hall where time is immutable and there are no second chances? Yet the opposite is true – any such artistic reticence is routed by the electrifying presence of an audience and its stimulation. Not only in classical music but in jazz, blues, rock, reggae – indeed, any genre – our most absorbing recordings invariably are made during concerts. As an extreme example, Furtwängler's vast reputation is almost wholly based on tapes of his inspired broadcasts rather than his comparatively staid studio work. Indeed, Walter's early (1941-43) American studio recordings with the NY Philharmonic of Beethoven's Symphonies 3, 5 and 8 – according to René Quonten, chosen by Columbia to compete with RCA's issuance of the same three symphonies by Toscanini and the NBC – and the "Emperor" Concerto with Serkin are solid but essentially mainstream readings and lack the heady inspirational freedom of his contemporaneous concerts.

At first it seems counterintuitive – shouldn't an artist be willing to take more risks in the studio where miscalculations or gaffes can be redone (or, in the tape and digital eras, repaired with patches from parallel takes) than in the concert hall where time is immutable and there are no second chances? Yet the opposite is true – any such artistic reticence is routed by the electrifying presence of an audience and its stimulation. Not only in classical music but in jazz, blues, rock, reggae – indeed, any genre – our most absorbing recordings invariably are made during concerts. As an extreme example, Furtwängler's vast reputation is almost wholly based on tapes of his inspired broadcasts rather than his comparatively staid studio work. Indeed, Walter's early (1941-43) American studio recordings with the NY Philharmonic of Beethoven's Symphonies 3, 5 and 8 – according to René Quonten, chosen by Columbia to compete with RCA's issuance of the same three symphonies by Toscanini and the NBC – and the "Emperor" Concerto with Serkin are solid but essentially mainstream readings and lack the heady inspirational freedom of his contemporaneous concerts.

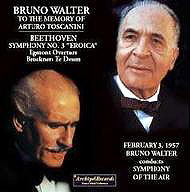

Walter would return twice to the NBC Symphony – in March 1951 to substitute for Toscanini who had injured his knee, and for a February 3, 1957 Toscanini memorial concert with the "Symphony of the Air," the remnants of the NBC Symphony which the network had disbanded after Toscanini's 1954 retirement but which survived for another decade both under guest conductors and in leaderless concerts intended to recall and preserve his spirit. Perhaps in deference to the occasion and the style of his late colleague, for his memorial tribute Walter crafted a rendition of the Beethoven Eroica, that melds Toscanini's resolute drive (and outsized tympani) with his own patient tempos and humanistic bent.

As with Mahler, Walter's European reputation was built at least as much at the opera house as in the concert hall. Yet, as with nearly all opera conductors, as he aged his career turned increasingly to orchestral concerts largely as a matter of stamina and efficiency – weeks of concerts could be prepared with the time and energy required for a single opera production.

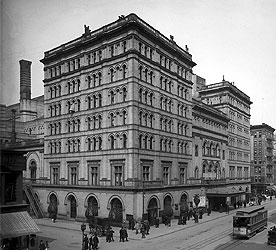

The old (pre-Lincoln Center) Met – "brewery" exterior; lavish interior |

Beethoven: Fidelio (February 22, 1941) – Our first complete opera directed by Walter in America is in many ways the most remarkable of all. In terms of sheer conducting, it's the most viscerally gripping and inspired Fidelio on record, constantly using tempo as an emotional barometer, but without threatening the continuity or effectiveness of the musical values or the characterization of the protagonists. Thus the opening duet is breathless but then relaxes for the central section of Marcellina's reverie and never quite recaptures the initial ardor – a fine depiction of the complex, conflicted emotions of a flighty youth facing the responsibilities of adulthood. The two overtures (Fidelio and Leonore 3) are utterly electrifying in their reckless speed and power and project a spontaneous outpouring rather than a patient construction of the recording studio. The two extended finales push the trite plot points far to the side and emerge as oratorios that throb with human passion to underscore the essential moral themes. Although our focus is on Walter, we should note that the singers are a dream cast: Kirsten Flagstad (Leonore), René Maison (Florestan), Herbert Janssen (Don Fernando), Julius Huehn (Don Pizarro) and Alexander Kipnis (Rocco). Solo voices constantly quake with excitement to craft a deeply human document that explores complexity beneath the surface of the plain text, all the while projecting the essence of the characters. Even Pizarro impresses as a man of sincere (albeit misguided) conviction amid a lurking aura of evil rather than a one-dimensional archvillain of pure malevolence, and Rocco struggles to muster enthusiasm for his vile work as a prison flunky and thus summons the painful compromises we all face in life. Despite being preserved in relatively thin sound, this is an altogether exalting and exhilarating experience. Although this recording was of the second matinee performance, the opening night critics raved about Walter. Pitts Sanborn in The New York World Telegram dubbed it a "red letter night" at the Met and singled out as "a perpetual delight" Walter's "feeling for every phrase of the music and his understanding of its large design" that "wrought the audience to such a pitch of enthusiasm that one trembled for the safety of the august house." Francis D. Perkins in The New York Herald Tribune agreed that "for Mr. Walter's American operatic debut [Fidelio] is a work which he not only understands completely but loves whole heartedly, with his ability to communicate his enthusiasm to the artists on the stage, the musicians in the pit and to the hearers in the audience." Citing cheers, vigorous applause and ovations throughout the "exceptional success," he noted in particular that "Mr. Walter had to wait two minutes or more after an inspiring conclusion of the Third Leonore Overture before the demonstration subsided sufficiently to allow him to begin the final scene."

Mozart: Don Giovanni (March 7, 1942) – Next at the Met Walter reprised his Salzburg success, with Pinza again in the title role. This Don Giovanni still garners universal and ecstatic praise, not only for Pinza's full realization but for Walter's leadership.

Ezio Pinza as Don Giovanni / Kirsten Flagstad as Leonora |

Walter followed his triumph of Don Giovanni with Le nozze di Figaro, another Salzburg Mozart reprise with Pinza, of which we have a full recording of the January 29, 1944 performance, and the Magic Flute, of which only a recording of a 1954 revival has emerged, together with Verdi's La forza del destino (recorded on January 27, 1943) and Un ballo in maschera (January 15, 1945), but while well received, none generated quite the ecstatic acclaim of Fidelio or Don Giovanni. (As a quirky aside, the Boston Herald critic found Walter's 1944 Figaro "wholly enchanting" but, possibly colored by wartime chauvanism, raised an objection: "What possible, conceivable excuse is there for doing this piece in Italian? It is perfectly preposterous to have a cast, more than half of which is American born, reciting jokes in a foreign language.")

Like so many esteemed European musicians who came to America during the War, immeasurably enriching our society and shifting the musical center of gravity further west across the Atlantic (just among conductors: Toscanini, Klemperer, Steinberg, Leinsdorf), Walter remained (and became a U.S. citizen in 1946).

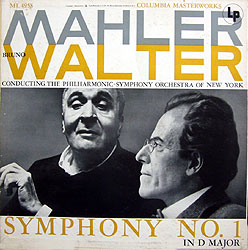

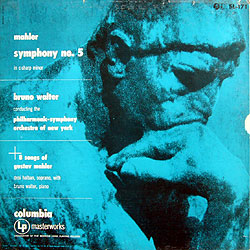

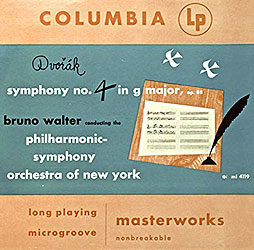

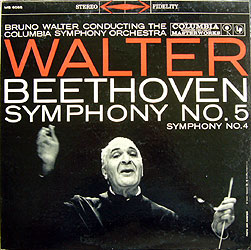

Although in demand for concerts throughout the U.S., for the final decade of the mono era he recorded almost exclusively for Columbia with the New York Philharmonic (then called the Philharmonic-Symphony Orchestra of New York), focusing on Mahler and complete cycles of the Beethoven, Brahms and late Mozart symphonies. All but the Mahler would be supplanted by stereo remakes and are rarely heard nowadays, but to many collectors they remain the peak of Walter's mature art.

Although in demand for concerts throughout the U.S., for the final decade of the mono era he recorded almost exclusively for Columbia with the New York Philharmonic (then called the Philharmonic-Symphony Orchestra of New York), focusing on Mahler and complete cycles of the Beethoven, Brahms and late Mozart symphonies. All but the Mahler would be supplanted by stereo remakes and are rarely heard nowadays, but to many collectors they remain the peak of Walter's mature art.

The Beethoven symphonies – Walter's Philharmonic Beethoven cycle actually began with two outliers – the solid 1941 Eighth, which was the most vivid of the three cut that year (and in 1948 had the honor of being the first recording released by Columbia in its new 10-inch LP format, bearing catalog number ML-2001); and a 1946 Sixth ("Pastoral") with the Philadelphia Orchestra, whose smooth, colorful sound was seemingly an ideal pairing for Beethoven's paean to nature. Yet while the first two movements are fluidly played and emerge as gentle and soothing without wallowing in sentiment the rest seems comparatively bland and disappointingly lethargic. Walter cut the other seven with the Philharmonic, beginning in 1947 with the First, nicely poised between light and depth, jaunty youth and a herald of the weightier symphonies to come. Next in 1949 came the Third ("Eroica") in an eminently musical reading that favors abstraction over highlighting its thematic overtones, fundamentally smooth and patient with just enough force to suggest rather than underscore its revolutionary spirit. The Ninth ("Choral") is a curious hybrid. First made and released intact in 1949, the finale was replaced in 1953 and the result reissued, both on a double LP with the 1941 Beethoven Eighth filling the fourth side and, by splitting the third movement, cramming all 66 minutes onto a single LP with surprisingly decent fidelity (although my pressing is afflicted with a bad speed change toward the end in the 2/2 section as the soloists and chorus sing "Tochter aus Elysium"). It's a decent, middle-of-the-road reading that was welcomed at the time but – and I admit that I've undoubtedly been spoiled by so many more distinctive Ninths – others have had much more to say in this remarkable landmark work.

Walter's 1950 Fifth is two minutes slower than his 1941 version and takes a similar middle path in a work that others bend to their firm attitudes – Toscanini's unremitting vigor, Scherchen's reckless haste, Klemperer's granitic sturdiness, Furtwängler's mystical probing – impersonal, perhaps, but not in the sense of dull or uncaring, but rather letting the glorious music unfold inevitably and logically, neither dragging nor carried away.

Walter's 1950 Fifth is two minutes slower than his 1941 version and takes a similar middle path in a work that others bend to their firm attitudes – Toscanini's unremitting vigor, Scherchen's reckless haste, Klemperer's granitic sturdiness, Furtwängler's mystical probing – impersonal, perhaps, but not in the sense of dull or uncaring, but rather letting the glorious music unfold inevitably and logically, neither dragging nor carried away.

Two of the last three in the set display the greatest personality. 1951 brought a Seventh which displays the bounds of Walter's disposition of the time. The introduction avoids undue dwelling on atmosphere, the joy of the ensuing Vivace is tempered by a touch of gravity, the Allegretto molds plastic tempos into an empathetic whole, the Presto is thick but poised between dance and repose, and the finale is quick and energetic. The orchestral balance boosts the winds at the expense of strings (at least on my original LP; CD remastering might reduce it), thus anticipating the texture of historically-informed performances of a later generation. The Fourth (1952) is ideally paced, with sufficient power but always couched in expressive feeling, accents muted just enough to blend in and Walter's trademark lyricism well in evidence, at least until the finale which declines a temptation to soar. The final entry is a 1953 Second that opens patient and rich while moving forward without losing momentum but then bogs down in the Larghetto, recovers somewhat in the Scherzo and ends with an Allegro molto that just isn't all that molto. (Perhaps Walter was least fond of this one but dutifully included it to complete the cycle?) A supplement of sorts was a 1949 Triple Concerto with an especially tight-knit and home-brewed set of soloists – the orchestra's concertmaster John Corigliano, its first cellist Leonard Rose and its assistant conductor Walter Hendl on piano – for whom Walter provides an earnest setting, nurturing yet muscular and fleet, fully mindful of the genre's roots in the baroque era of less personal interpretive input.

Also worth noting is a live 1948 Missa Solemnis that crackles with volatile untamed fervor and elemental visceral excitement, constantly pushing tempos and dynamics to the extreme, drawing deeply committed singing and playing, and holding its sections together – but only barely – with thrilling tension.